Trade in Maya civilization facts for kids

The Maya civilization was an amazing ancient culture in Mesoamerica. For their cities to thrive, trade was incredibly important. It helped them get everything they needed and wanted.

The Maya traded many things. This included foods like fish, squash, yams, corn, honey, beans, turkey, vegetables, salt, and chocolate drinks. They also traded raw materials such as limestone, marble, jade, wood, copper, and gold. Manufactured goods included paper, books, furniture, jewelry, clothing, carvings, toys, and weapons.

Beyond goods, the Maya also had skilled people who offered services. These included mathematicians, farming experts, artisans, architects, astronomers, scribes, and artists. Richer merchants sometimes sold valuable items like weapons and gold. Special craftsmen made luxury items or tools to solve problems, often for the rulers.

Trade wasn't just local. The Maya also traded over long distances for necessities like salt, stone, and luxury items that weren't found nearby. Different regions often specialized in producing certain goods.

Contents

How Maya Trade Worked

The Maya economy involved many different people. There was a strong group of skilled workers and artisans. These people made everyday items and special goods. Above them were merchants who managed trade in different regions. They understood what people needed and arranged for goods to be bought and sold.

Even higher were highly skilled specialists. These included artists, mathematicians, architects, and astronomers. They offered their unique talents and created beautiful luxury items. At the very top were the structure were the rulers and their advisors. They managed trade with other kingdoms. They also made sure regions were stable and supported big building projects.

For a long time, some historians thought Maya trade was very simple. They believed rulers controlled everything. However, new discoveries show that Maya cities were very active and organized. They had busy marketplaces where many goods were exchanged. This included important items like obsidian.

Evidence from places like Calakmul shows murals depicting specialists in what looks like a market area. The ancient Yucatec Maya language even had words for "market" and "where one buys and sells." This tells us that marketplaces were a real part of Maya life. Large cities like Coba also had marketplaces in their main plazas. These areas show signs of many organic goods being traded there.

Maya Forms of Payment

The Maya did not use "money" in the same way we do today. Instead, they used different items for exchange. For large amounts of food, they often used a barter system. This means they traded one item directly for another.

For everyday purchases, especially in later times, cacao beans were commonly used. Imagine using chocolate beans as payment! For more expensive items, valuable materials like gold, jade, and copper were used. It's important to remember that the value of these items could change from one city or region to another.

How Trade Grew in the Maya World

In most Maya areas, local resources and merchants were easy to find. This meant small towns often traded only with their neighbors. They didn't need to travel far for goods. However, even farming families, who made up most of the population, still needed to trade for some necessities. These often included pottery, tools made of bronze or copper, salt, and fish for those living inland.

As craftsmen in smaller cities became more specialized, and as cities grew larger, the need for more trade increased. Big cities like Tikal and El Mirador are good examples. Tikal, for instance, had a huge population of 60,000 to 120,000 people. This meant it needed food and other goods from up to 100 kilometers away! To manage such a large system, rulers gained more power over their lands and people.

Trade routes also helped smaller, once-isolated cities grow. More goods and people passing through meant these towns became more important. This led to steady growth across the Postclassic period.

Over the last few decades, discoveries have shown just how widespread Maya trade was. Scientists have studied ancient artifacts. Using modern chemical tests, they confirmed that many items came from very far away. This proves that goods like hard stones, honey, and quetzal feathers traveled great distances across the Maya region.

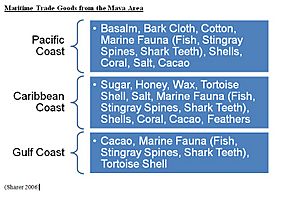

The Maya moved many goods over long distances. These included salt, cotton cloth, quetzal feathers, flint, chert, obsidian, jade, colored shells, cacao, and copper tools and ornaments. Since they didn't have wheeled carts or large animals to carry heavy loads, these goods were often transported by sea or along rivers.

Because the Maya were so good at making and trading a wide variety of goods, they built a lifestyle based on trade throughout all of Mesoamerica. This connected them with many different groups of people. Some historians believe that their skill as traders might have helped them avoid being conquered by the powerful Aztec empire. The Aztecs valued the Maya for their trade abilities, so they didn't feel the need to take over their lands.

Trade also helped different cultures mix. For example, when the Maya traded with the Teotihuacan civilization, their building styles, religious ideas, and art began to blend together.

Important Goods Traded by the Maya

As trade grew, especially in the Postclassic period, the demand for many goods increased. Many of these items were made in large, specialized workshops. These workshops were almost like factories! Goods were then transported, often by sea, because roads were not always good for heavy cargo.

Some of these important goods included fine ceramics, stone tools, paper, jade, pyrite, quetzal feathers, cacao beans, obsidian, copper, bronze, and salt.

Most ordinary people used basic goods like stone tools, salt, cacao beans, fish, and manufactured items such as books, ceramics, and wood products. However, valuable raw materials like gold, jade, copper, and obsidian were mostly used by the upper class and rulers. They used these items to show their power and wealth.

Salt: A Vital Resource

Salt was perhaps the most important traded item. It was essential for the Maya diet. But it was also critical for keeping food fresh! By covering meat and other foods with salt, the Maya could dry them out. This stopped the food from spoiling.

Most salt was made near the oceans. People would dry out large areas of seawater. Once the water evaporated, the salt could be collected and moved across the Maya lands. The Yucatán Peninsula was the biggest producer of salt in all of Mesoamerica. People there specialized in collecting sea salt, which was the most valuable kind.

Ancient Tikal, with its large population, needed a lot of salt every year. Besides food, salt was also used in important rituals and for health purposes. For example, it was used in some protective gear for warriors, like cotton jackets filled with rock salt.

Three main sources of salt supplied the Maya in the Petén Lowlands. These were the Pacific Lowlands, the Caribbean coast, and the Salinas de los Nueve Cerros. The Salinas de los Nueve Cerros, located in the highlands of Guatemala, produced black salt from natural brine springs. Other inland sources also existed and are still used today.

The Maya used special clay pots to boil brine (salty water) to make salt blocks. These pots were used once and then discarded. Near the Pacific Lowlands, platforms were used to dry salt using the sun. These platforms, found near La Blanca, might be the oldest in Mesoamerica. Once made, salt was often transported along rivers like the Chixoy and Usumacinta.

Ceramics and Fine Furniture

Workshops specialized in making ceramics and furniture. These items were then traded for other goods. Often, the work of a particular artist or workshop was highly desired by the wealthy Maya. These artists were usually supported by the rich and created items mainly for them.

Luxury art goods also moved between kingdoms and local areas among the elite. These included jade carvings, paintings, fancy furniture, and metal ornaments. Such items were strong symbols of power and wealth. The ceramics made were mainly plates, vases, and tall drinking cups. When painted, these pots often featured red, gold, and black designs.

Jade and Obsidian: Precious Stones

Rare stones like jade and pyrite were very important to the Maya elite. These stones were hard to find, so owning them helped rulers show their high status. Many of these stones were collected in the highlands of Guatemala. As long-distance trade grew, more of these precious stones could be moved to the lowland cities.

The main route for jade was along the Motagua river and a newly found land route in the Sierra de las Minas. From there, it was sent across the Maya area and beyond. Canoes were used on Caribbean routes and the Pasión River. A unique item often becomes more valuable the farther it travels from its source.

For example, jade axes found on the island of Antigua had traveled a very long way. This shows how far Maya trade networks reached. Guatemala is considered the main source of jade in the New World.

The city of Cancuén seemed to thrive for hundreds of years without much warfare. Trade appeared to be more important there than religion in daily life. This challenges the idea that Maya rulers only gained power through religion and war, especially after 600 A.D.

Obsidian was another vital stone. It was transported from quarries like El Chayal, San Martín Jilotepeque, and Ixtepeque. Rivers connected these quarries to the Motagua River. From the Caribbean coast, obsidian was then moved using river systems like the Río Azul, Holmul River (Guatemala), and Mopan River. This distributed it to major centers in Petén.

In El Baúl Cotzumalguapa, large workshops made obsidian tools. They produced sharp blades and projectile points. These required special skills and organized production. The main goal was to supply cutting tools, throwing weapons, and instruments for scraping and polishing. These were all used in daily household tasks.

Changes in the economy during the shift from the Classic to the Postclassic periods, along with more trade by water, allowed for even greater long-distance trade. This meant these important goods could reach every part of the Maya region.

See also

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |