Spanish conquest of Chiapas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish conquest of Chiapas |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish conquest of Mexico | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Zoque people

|

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Pedro de Portocarrero Pedro de Alvarado |

Diego de Mazariegos Jacinto de Barrios Leal |

||||||||

The Spanish conquest of Chiapas was a long fight by Spanish conquistadores (explorers and conquerors) to take control of the land that is now the Mexican state of Chiapas. This region has many different types of land. It has high mountains, a flat coastal area called Soconusco, and a central valley with the Grijalva River.

Before the Spanish arrived, many different groups of native people lived in Chiapas. These included the Zoques, various Maya peoples, and a group called the Chiapanecas. The Aztecs, a powerful empire from central Mexico, had already taken over Soconusco and made its people pay tribute.

The people of Chiapas first heard about the Spanish when the Spanish took over the Aztec Empire. In the early 1520s, Spanish explorers traveled through Chiapas. Spanish ships also explored the Pacific coast. The first Spanish town in the highlands of Chiapas was San Cristóbal de los Llanos. It was started by Pedro de Portocarrero in 1527.

Soon, the Spanish controlled the Grijalva River area, Comitán, and the Ocosingo valley. They set up a system called encomienda. This system gave Spanish settlers control over groups of native people. It often meant they could force the natives to work or pay tribute.

In 1528, Diego Mazariegos created the colonial province of Chiapa. He renamed San Cristóbal to Villa Real and moved it to Jovel. The Spanish demanded too much from the native people. This led to a rebellion. The natives tried to starve the Spanish out. The Spanish fought back, but many natives left their towns and hid in hard-to-reach places.

Problems among the Spanish themselves caused more trouble. But eventually, Mazariegos's group got special permission from the Spanish king. Villa Real became a city called Ciudad Real. New laws were made to bring peace to the area.

Contents

Geography of Chiapas

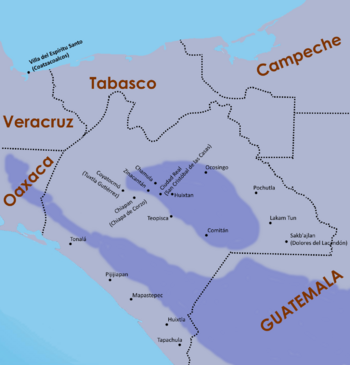

The state of Chiapas is in the very southeast of Mexico. It covers about 74,415 square kilometers (28,732 sq mi). To the west, it borders other Mexican states. To the north, it borders Tabasco. To the east, it borders Guatemala. Its southern edge is 260 kilometers (160 mi) of Pacific coastline.

Chiapas has diverse landscapes and cultures. It has two main mountain ranges. The Sierra Madre de Chiapas is in the south. The Montañas Centrales (Central Highlands) are in central Chiapas. A central valley, called the Depresión Central, separates these mountains. The Grijalva River flows through this valley.

The littoral zone of Soconusco is south of the Sierra Madre mountains. It is a narrow coastal plain with hills. This area has a humid, tropical climate and rich farmland.

The Depresión Central is a valley about 200 kilometers (120 mi) long. It is 30 to 60 kilometers (19 to 37 mi) wide. The Grijalva River gets water from mountains in Guatemala and Chiapas. This area has a hot climate with some rain.

The Central Highlands rise steeply north of the Grijalva River. They reach up to 2,400 meters (7,900 ft) high. Then they gently slope down towards the Yucatán Peninsula. This area has many deep valleys and rivers. It gets a lot of rain. The plants here change with the height. They include pine forests and tropical rainforests. The Lacandon Forest is at the eastern end of the Central Highlands.

Chiapas Before the Spanish Arrived

The first people in Chiapas were hunter-gatherers. They lived in the northern highlands and along the coast from about 6000 BC. For about 2,000 years before the Spanish arrived, most of Chiapas was home to people who spoke Zoque. Later, people who spoke Mayan languages moved in from the east. By about 200 AD, Chiapas was split. The Zoques lived in the west, and the Maya lived in the east. This was still true when the Spanish came.

The Zoques lived in a large part of western Chiapas. Their main towns included Copainalá and Tecapatán. The Aztecs made the Zoques pay tribute. The Aztecs also controlled trade routes through their land. The Depresión Central had two of the biggest cities in the region: Chiapa and Copanaguastla.

The area around Chiapa de Corzo was home to the Chiapanecas. We don't know their language or exact background. But they were very strong fighters before the Spanish arrived. They made many Zoque towns pay them tribute. They also successfully fought off the Aztec Empire. Their land was between the Zoques and the Tzotzil Maya. Their main towns included Chiapa and Suchiapa.

The central highlands were home to several Maya groups. These included the Tzotzil, who had many smaller areas. The Tojolabal Maya lived around Comitán. The Coxoh Maya lived near the Guatemalan border. They were likely a part of the Tojolabal group.

Soconusco was an important trade route. It connected central Mexico with Central America. The Aztec Triple Alliance took over Soconusco in the late 1400s. They made the people pay tribute in cacao (chocolate beans). The Cholan Maya-speaking Lakandon people lived in eastern Chiapas and southwestern Guatemala. They were known for being fierce fighters.

First Contacts with the Spanish

People in Chiapas heard rumors about strangers on the Atlantic coast long before the Spanish arrived. The Aztec emperor, Moctezuma II, even sent messages to the Kʼicheʼ Maya in Guatemala. He warned them to get ready for war against the Spanish. Soon after, news came that the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, had fallen to the conquistadores.

A group of people, including Chiapanecas, Kʼicheʼs, and Kaqchikel Maya, visited Hernan Cortés in the Aztec capital. Cortés welcomed them.

In 1522, Spanish ships explored the Pacific coast of Chiapas. In December of that year, the lord of the Tzotzil Maya town of Zinacantan traveled to a Spanish settlement. He wanted to make an alliance with the Spanish.

Spanish Methods of Conquest

The Spanish conquest had two main goals. First, they wanted to bring the native people of Chiapas into the Spanish Empire. Second, they wanted to convert them to Christianity. This meant changing how native societies worked. They destroyed native temples and idols. They moved native people into new, central towns. This made it easier to control them and teach them Christianity. These new towns also had to pay Spanish tributes and taxes.

The conquest involved fighting and setting up Spanish rule by force. But the religious side was usually peaceful. Dominican friars led these efforts. They helped move native people into new towns. They built churches and taught Christianity.

Spanish conquistadores in the 1500s used swords, crossbows, and early guns. Soldiers on horseback used long lances. They also used different kinds of axes and spears. Crossbows were easier to keep working than guns, especially in the hot, wet climate.

Heavy metal armor was not very useful in the tropics. It was hot, heavy, and rusted easily. So, conquistadores often wore quilted cotton armor. This was like the armor used by native fighters. They also wore simple metal helmets. Shields were very important for both foot soldiers and cavalry.

The encomienda system was set up to get labor from native people. But in the early days, it often meant slave raids. The Spanish would capture native people, brand them as slaves, and sell them. They used the money to buy horses and weapons. This helped them conquer more land and get more slaves.

The Tzotzil Maya of highland Chiapas used spears, rocks, bows and arrows. They also had large cotton shields that covered their whole body. Towns sometimes had walls and barricades made of earth, stone, and tree trunks. Defenders would throw stones or pour boiling water mixed with lime and ash on attackers. As the Spanish settled in Chiapas, native resistance often meant fleeing to remote areas.

Diseases from Europe

Before the conquest, Chiapas had many people. But diseases from Europe caused a huge drop in population. This is why the hot, wet lands of the Depresión Central are still not very populated today. Soconusco also lost many people very quickly due to disease. The most deadly diseases were smallpox, influenza, measles, and lung diseases like tuberculosis.

Conquest of Soconusco

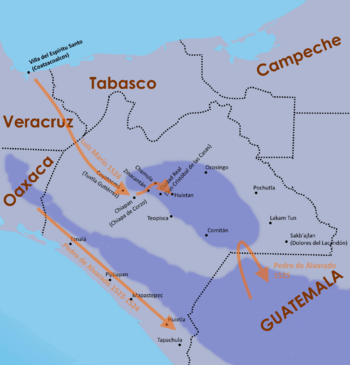

Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado marched through Soconusco in 1523. He was on his way to conquer Guatemala. Alvarado's army included experienced soldiers from the Aztec conquest. It also had many native allies from central Mexico.

The people of Soconusco welcomed Alvarado peacefully. They promised to be loyal to the Spanish king. They told Alvarado that their neighbors in Guatemala were attacking them because they were friendly to the Spanish. By 1524, Alvarado had fully brought Soconusco under Spanish control.

Over the next 50 years, the native population dropped by 90-95% due to European diseases. Even so, the Spanish demanded twice as much cacao tribute as the Aztecs had. Cacao remained a very important crop. The Spanish did not want to move the native people far from their cacao farms. This is because new cacao trees take five years to grow.

Soconusco's control changed often. At first, it was controlled by Hernán Cortés. Then it was controlled by the Audiencia Real of Mexico (a high court). Later, it came under the Audiencia Real of Guatemala.

Church control also changed a lot. It was first under the Diocese of Tlaxcala, then Guatemala, then Chiapa, and back and forth. The Dominican friars worked in Soconusco early on. But they left in 1545 because there were few native people left and the climate was unhealthy.

Early Spanish Expeditions, 1524–1525

Luis Marín's Journey, 1524

In 1524, Luis Marín led a small group into Chiapas. He started from Coatzacoalcos on the Gulf of Mexico coast. His group went through Zoque land and followed the Grijalva River. Near modern Chiapa de Corzo, the Spanish fought and defeated the Chiapanecos.

After this battle, Marín went into the central highlands. Around Easter, he passed through the Tzotzil Maya town of Zinacantan. The people there did not fight. They had promised loyalty to the Spanish two years earlier. They helped the Spanish against other native groups.

Marín reached Chamula, another Tzotzil town. At first, they sent a peaceful message. Marín thought this meant they would surrender. But when he tried to enter, they fought back. The Chamula Tzotzil had left their lands and taken all the food. This was to make the Spanish leave.

The next day, Marín found the Chamula Tzotzil warriors on a ridge. It was too steep for Spanish horses. The conquistadores faced a rain of stones, spears, and arrows. They also had boiling water mixed with lime and ash thrown at them. The nearby town had a strong 4-meter (13 ft) thick wall. It was made of stone, earth, and tree trunks. The Tzotzil made fun of the Spanish. They threw small bits of gold and dared them to take more.

The Spanish attacked the wall. They found that the people had left spears inside to trick them. The Tzotzil had actually left during a heavy rain. After taking the empty Chamula, the Spanish went to Huixtan. The people there also fought before leaving their town. A conquistador named Diego Godoy said no more than 500 natives were killed or captured at Huixtan. The Spanish were disappointed by the lack of riches. They decided to go back to Coatzacoalcos in May 1524.

The Spanish had hoped to find many people who would quickly surrender. They wanted to divide them up for forced labor. But the strong resistance quickly ended these hopes. However, within two years, encomienda rights were given out. These were used to justify taking slaves. Chamula was given to Bernal Díaz, and Zinacantan to Francisco de Marmolejo.

Pedro de Alvarado's Expedition, 1525

A year later, Pedro de Alvarado entered Chiapas again. He crossed part of the Lacandon Forest. He was trying to meet up with Hernán Cortés, who was going from Mexico to Honduras. Alvarado entered Chiapas from Guatemala. He could not find Cortés. His scouts led him to Tecpan Puyumatlan (now Santa Eulalia in Guatemala). This was a mountain area near the Lakandon Chʼol.

The people of Tecpan Puyumatlan fought fiercely against Alvarado's army. Gonzalo de Alvarado wrote that the Spanish lost many men. This included messengers sent to ask the natives to swear loyalty. After failing to find Cortés, the Alvarados went back to Guatemala.

Conquest of the Chiapas Highlands, 1527-1547

Highland Chiapas, called Chiapa, was part of New Spain until 1530. Then it was moved to Guatemala. In 1540, Chiapa became self-governing for four years. After that, it was again part of Guatemala. The capital of Chiapa province was Ciudad Real, now San Cristóbal de las Casas.

Pedro de Portocarrero led the next Spanish group into Chiapas. He came from Guatemala. Not much is known about his campaign. But in January 1528, he successfully started San Cristóbal de los Llanos. This was in the Comitán valley, in Tojolabal Maya land. This town became a base for the Spanish to expand control towards the Ocosingo valley. There was some native resistance, but we don't know how much. The Coxoh Maya were likely conquered in 1528. The Spanish moved them into five small new settlements.

By 1528, Spanish power was set in the Chiapas Highlands. Encomienda rights were given to conquistadores. Spanish control spread from the Grijalva River area to Comitán and the Ocosingo valley. This area became part of the Villa de San Cristóbal district. It included Chamula, Chiapan, and Zinacantán. The north and northwest were part of the Villa de Espíritu Santo district. This included Chʼol Maya and Zoque lands.

In the early years, encomienda rights often meant the right to raid for slaves. Spanish soldiers on horseback would quickly attack a native town. Prisoners were branded as slaves. They were taken to a port to be sold. The money was used to buy weapons, supplies, and horses. Sometimes, conquistadores would chain up elders, whip them, and set dogs on them. This was to force natives to give them food and clothing.

Diego Mazariegos Takes Control, 1528

In 1528, Captain Diego Mazariegos came into Chiapas. He brought cannons and new soldiers from Spain. These soldiers had no military experience. By this time, many native people had died from disease and hunger.

Mazariegos first went to Jiquipilas. He met people from Zinacantan. They had asked for Spanish help against rebellious groups. A small group of Spanish cavalry was enough to bring the Zinacantecos' rebels back under control. After this, Mazariegos went to Chiapan. He set up a temporary camp nearby, called Villa Real.

Mazariegos was related to the governor of New Spain. He was sent to create a new province called Chiapa in the highlands. At first, he faced resistance from the Spanish soldiers already there. Mazariegos met Pedro de Portocarrero and convinced him to leave. After three months of talks, an agreement was reached. The encomiendas in the highlands were taken from the Villa del Espíritu Santo area. They were combined with those of San Cristóbal to form the new province.

The king had already ordered that San Cristóbal de los Llanos be given to Pedro de Alvarado. But Mazariegos's talks led to Villa de San Cristóbal de los Llanos being broken up. Settlers who wanted to stay moved to Villa Real. This new Villa Real was moved to the fertile Jovel valley. Pedro de Portocarrero left Chiapas and went back to Guatemala.

Mazariegos continued to move native people into new, easy-to-control settlements. This was easier because fewer native people were left. For example, the town of San Andrés Larráinzar was created by moving Tzotzil people. Mazariegos gave out encomiendas in areas not yet conquered. This was to encourage settlers to conquer new land. The Province of Chiapa had no coast. About 100 Spanish settlers lived in the remote capital, Villa Real. They were surrounded by hostile native towns and had many internal problems.

Native Rebellion

Mazariegos had set up his new capital without fighting. But the Spanish demanded too much labor and supplies. This soon caused the native people to rebel. The colonists wanted food, wood for building, and firewood. They also wanted new houses built for them. Spanish pigs were also damaging the natives' cornfields.

In August 1528, Mazariegos replaced the existing encomenderos with his friends. The natives saw that the Spanish were isolated. They also saw the fighting between the old and new settlers. They used this chance to rebel. They refused to supply their new masters. Zinacantán was the only native settlement that stayed loyal to the Spanish.

Villa Real was now surrounded by enemies. Any Spanish help was too far away. The colonists quickly ran out of food. They took up arms and rode out to find food and slaves. The native people left their towns. They hid their women and children in caves. The rebels gathered on easily defended mountaintops.

At Quetzaltepeque, the Tzeltal Maya fought a long battle against the Spanish. Some Spanish died from rocks thrown from the mountaintop. The battle lasted several days. The Spanish were helped by native warriors from central Mexico. The Spanish eventually won. But the rest of Chiapa province remained rebellious.

After the battle, Villa Real still had little food. Mazariegos was sick. He sent his brother to the capital of New Spain to ask for help. Then he went to Copanaguastla, against the wishes of the town council. The council was left to defend the new colony.

By now, Nuño de Guzmán was governor in Mexico. He sent Juan Enríquez de Guzmán to Chiapa. He was to judge Mazariegos and act as the local governor. He held his post for a year. He tried to bring the province back under Spanish control, especially the north and east. But he did not make much progress.

Founding of Ciudad Real

The constant change of Spanish governors caused problems. Each new official gave out encomienda licenses to their friends. This made Chiapa province unstable. In 1531, Pedro de Alvarado finally became governor of Chiapa. He immediately changed Villa Real's name back to San Cristóbal de los Llanos. Again, the encomiendas of Chiapa were given to new owners.

The Spanish sent an expedition against Puyumatlan. It did not conquer the area. But it allowed the Spanish to capture more slaves. These slaves were traded for weapons and horses. The new supplies were then used for more expeditions. This created a cycle of slave raids, trading for supplies, and then more conquests and slave raids.

Alvarado sent his officer Baltasar Guerra to calm the rebel Chiapanecas and Zoques. The winning conquistadores then demanded encomiendas. The general instability continued. But the Mazariegos family built power in the local government. In 1535, the Mazariegos group succeeded. San Cristóbal de los Llanos was declared a city. It was given the new name of Ciudad Real. They also got special rights from the king to make the colony stable. For example, the governor of Chiapa had to govern in person.

The quick changes in encomiendas continued. Few Spanish men had legal Spanish wives and children who could inherit. This situation did not become stable until the 1540s. More Spanish women arrived, which helped. Also, the Audiencia de los Confines (a high court) stepped in. They appointed judges to control how encomiendas were given out.

The Dominicans Arrive

In 1542, new laws were made. These "New Laws" aimed to protect the native people from being overworked by the encomenderos. To enforce these laws, a fleet of 27 ships left Spain on July 19, 1544. On board was friar Bartolomé de las Casas and his religious followers. Las Casas arrived in Ciudad Real with 16 other Dominicans on March 12, 1545.

The Dominicans were the first religious group to try to convert the native people. Their arrival meant that colonists could no longer treat natives however they wanted. The church could now step in.

The Dominicans soon had problems with the colonists. They refused to hear confessions or give religious services to Spaniards who mistreated natives. They even put a church leader in prison and removed the president of the Audiencia Real from the church. The colonists' anger against the Dominicans grew so strong that the Dominicans had to flee Ciudad Real for their lives.

They settled in two nearby native villages. Las Casas stayed in the old site of Villa Real de Chiapa. Friar Tomás Casillas took charge of Cinacantlán. From Villa Real, Bartolomé de las Casas and his friends prepared to convert all the people in the Bishopric of Chiapa. Chiapas was divided into areas based on older native divisions. These included the Chiapaneca, Lakandon, Tojolabal, Tzeltal, and Zoque. The Dominicans promoted the worship of Santiago Matamoros (Saint James the Moor-slayer). This was a clear symbol of Spanish military power.

It soon became clear that the Dominicans needed to return to Ciudad Real. The fighting with the colonists calmed down. In 1547, while de las Casas was in Spain, Francisco Marroquín, bishop of Guatemala, laid the first stone for the new Dominican convent in Ciudad Real.

The Dominicans worked to destroy native temples and idols. They preached sermons with powerful images, like those from the Book of Revelation. These were more familiar to the native worldview. Saints were linked to animals, much like natives connected themselves with nahual spirit-forms. Different native ideas of the afterlife were tied to Christian ones. For example, the Mictlan world of the dead became Hell.

Conquest of the Lacandon Forest, 1559–1695

By the mid-1500s, the Spanish reached the Lacandon Forest from Comitán and Ocosingo. They could not go further because the people there were fiercely independent. In the 1500s, the Lacandon Forest was home to Chʼol people called Lakam Tun. The Spanish changed this name to Lacandon. These Lakandon Chʼol are not the same as the modern Lacandon people who live there today. The main Lakandon village was on an island in Lake Miramar.

The Lakandon were aggressive. Their numbers grew because other native people fleeing Spanish rule joined them. Church leaders were so worried that they eventually supported military action. The first Spanish expedition against the Lakandon was in 1559.

From time to time, the Spanish sent military groups against the Lakandons. They wanted to make the northern border of the Guatemalan colony stable. The biggest expeditions were in 1685 and 1695. These repeated trips destroyed some villages. But they could not fully control the people of the region or bring them into the Spanish Empire. This successful resistance against the Spanish attracted even more native people fleeing colonial rule.

Resistance continued. Hostile Chʼol people killed some newly baptized Christian natives. Franciscan friars Antonio Margil and Melchor López worked among the Lakandon and Manche Chʼol from 1692 to 1694. But they eventually wore out their welcome and were forced out by the Chʼol.

In 1695, the Spanish decided to connect the province of Guatemala with Yucatán. Soldiers led by Jacinto de Barrios Leal, president of the Real Audiencia of Guatemala, conquered some Chʼol communities. The most important was Sakbʼajlan on the Lacantún River in eastern Chiapas. It was renamed Nuestra Señora de Dolores in April 1695. This was part of a three-part attack against the independent people of Chiapas and Petén. A second group joined Barrios Leal from Huehuetenango, Guatemala. The third group marched from Verapaz, Guatemala, against the Itza of northern Petén.

Barrios Leal was joined by Franciscan friar Antonio Margil. Margil was an advisor, confessor, and chaplain to the troops. The Spanish built a fort and put 30 soldiers there. Mercederian friar Diego de Rivas was based at Dolores del Lakandon. He and other Mercederians baptized hundreds of Lakandon Chʼols in the next few months. They also made contact with nearby Chʼol communities.

Antonio Margil stayed in Dolores del Lakandon until 1697. The Chʼol people of the Lacandon Forest were moved to Huehuetenango, Guatemala, in the early 1700s. The resettled Lakandon Chʼol soon blended into the local Maya populations. They stopped existing as a separate group. The last known Lakandon Chʼol were three natives recorded in Santa Catarina Retalhuleu in 1769.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Conquista española de Chiapas para niños

In Spanish: Conquista española de Chiapas para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |