Spanish conquest of Honduras facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish conquest of Honduras |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas | |||||||||

Painting by Hidalgo Lara of Lempira fighting a Spanish conquistador. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Indigenous peoples of Honduras, including:

|

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

The Spanish conquest of Honduras was a time in the 1500s when Spain took control of the land we now call Honduras. This country is one of the seven states in Central America. In 1502, Christopher Columbus claimed this land for the king of Spain during his last trip to the New World.

Before the Spanish arrived, many different native groups lived in Honduras. These included the Maya, Lenca, Pech, Miskitu, Mayangna (Sumu), Jicaque, Pipil and Chorotega. Two brave native leaders fought hard against the Spanish: Sicumba, a Maya leader, and Lempira, a Lenca ruler. Lempira's name means "Lord of the Mountain."

In March 1524, Gil González Dávila was the first Spaniard to arrive in Honduras to conquer it. He started the first Spanish port on the Caribbean coast, called Puerto de Caballos. This port became important for future trips. The early years of the conquest were messy. Different Spanish groups from Mexico, Hispaniola, and Panama all tried to take over the land. This led to fights among the Spanish themselves.

By 1530, the Spanish colonists had a lot of power. They even chose and removed governors. The Spanish government in Honduras was full of arguments. To stop the chaos, the colonists asked Pedro de Alvarado for help. Alvarado arrived in 1536 and ended the fighting. He also won an important victory against Sicumba, a Maya leader in the Ulúa Valley. Alvarado founded two towns that became very important: San Pedro de Puerto Caballos (now San Pedro Sula) and Gracias a Dios.

In 1537, Francisco de Montejo became the new governor. He changed the land distribution that Alvarado had made. That same year, a big native uprising started across Honduras. It was led by the Lenca ruler Lempira. Lempira bravely defended his strong fort at the Peñol de Cerquín for six months. He was eventually killed, but his rebellion almost ended the Spanish colony in Honduras. After Lempira's death, Montejo and his captain Alonso de Cáceres quickly took control of most of Honduras. The main part of the Spanish conquest was finished by 1539. However, areas like Olancho and the eastern parts were not fully controlled for many more years.

Contents

- Geography of Honduras

- Honduras Before the Spanish Arrived

- How the Conquest Started

- Spanish Soldiers and Their Ways

- Native Weapons and Fighting Styles

- Discovery of Honduras

- First Spanish Expeditions

- Rival Spanish Groups in the 1520s

- Hernán Cortés in Honduras, 1525–1526

- Crown Takes Control, 1526–1530

- Ch'orti' Resistance, 1530–1531

- Chaos in the Colony

- Sicumba, Lord of Ulúa Valley

- Decline of Higueras-Honduras

- Pedro de Alvarado Arrives, 1536

- Temporary Decline, 1536–1537

- Francisco de Montejo's Arrival

- Olancho and the East in the 1540s

- Founding of Colonial Tegucigalpa

- Province of Taguzgalpa

- Challenges in the 1600s

- Historical Sources

- See also

Geography of Honduras

Modern Honduras is in the middle of Central America. It covers about 112,090 square kilometers (43,278 square miles). This makes it the second-largest country in Central America. Most of the country's inside is mountainous.

Honduras is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north. To the west, it borders Guatemala. To the southwest, it borders El Salvador. And to the southeast, it borders Nicaragua. In the very south, Honduras has a small coastline on the Gulf of Fonseca. This gives it access to the Pacific Ocean.

The country has four main geographic areas. The largest part is the mountainous highlands, covering about two-thirds of the land. The highest mountain range is the Sierra del Merendón. It runs from southwest to northeast. Its highest point is Cerro Las Minas, at 2,850 meters (9,350 feet) above sea level.

The Nombre de Dios mountain range is south of the Caribbean coast. It is not as rugged and reaches 2,435 meters (7,989 feet) high. The Entre Ríos mountains are along part of the Nicaraguan border. The highlands have many fertile, flat valleys. These valleys are between 300 and 900 meters (980 and 2,950 feet) high. The Sula Valley goes from the Caribbean to the Pacific. It offers a path between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. This valley has Honduras' most important river, the Ulúa River. It flows 400 kilometers (250 miles) northeast into the Gulf of Honduras.

The Mosquito Coast is in the east, near Nicaragua. It is a dense rainforest. The Caribbean lowlands are a thin strip along the coast. In the middle, these lowlands are only a few kilometers wide. But in the east and west, they form wide coastal plains. A smaller lowland area is in the south around the Gulf of Fonseca. It is about 25 kilometers (16 miles) wide along its north coast.

The Bay Islands are off the Caribbean coast. The three big islands are Roatán, Utila, and Guanaja. Smaller islands include Barbareta, Cayos Cochinos, Helene and Morat. There are also over 60 tiny islands.

Climate in Honduras

Honduras has a tropical climate. It has a wet season and a dry season. Most of the rain falls between May and September. April is the warmest month, and January is the coolest. In the highland valleys, like Tegucigalpa, temperatures range from 23°C (73°F) to 30°C (86°F). Sometimes, frost forms at altitudes over 2,000 meters (6,600 feet).

Honduras Before the Spanish Arrived

When the Spanish first came to what is now Honduras, about 800,000 people lived there. Most of them lived in the western and central parts. Honduras was a border area between Mesoamerica (to the northwest) and simpler societies to the south and southeast.

Many parts of Honduras were in the "Intermediate Area." This region was seen as having less advanced cultures. But it still had strong connections with the Maya civilization and other Mesoamerican cultures.

The Pech people lived in the northeast of Honduras. The Miskito and Mayangna peoples also lived there. These groups had cultural ties to the south and east. The Lenca people lived in central and southwestern Honduras. They had strong cultural links to Mesoamerica.

The Jicaque people lived along the Atlantic coast. This was from the Ulúa River east to the Nombre de Dios mountains. The Chorotega and the Pipil were part of the Mesoamerican culture. The Pipil were in the north of Honduras. The Chorotega were in the south, near the Gulf of Fonseca.

The islands in the Gulf of Fonseca were home to Lenca and Nahua people. Early Spanish records show that important towns like Naco and Quimistan were multiethnic. They had Pipil, Lenca, or Maya people. Naco was a large trading center. It became an early target for Spanish expeditions.

The groups in northeastern Honduras were more isolated. They were not fully part of the trade networks. The western edge of Honduras was home to Maya peoples, including the Ch'ol and Ch'orti'. The Ch'ol lived around the Amatique Bay. The Ch'orti' lived in the upper Chamelecón River area.

How the Conquest Started

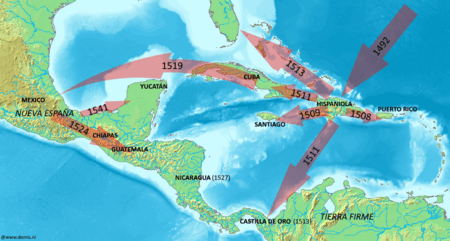

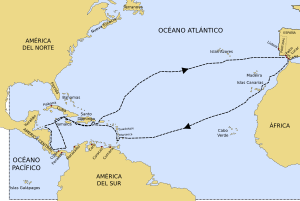

Christopher Columbus found the New World for Spain in 1492. After that, private adventurers made deals with the Spanish Crown. They would conquer new lands in exchange for taxes and power. The Spanish built Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola in the 1490s. In the early 1500s, they used Cuba as a base.

Even though Columbus found Honduras in 1502, no serious effort to conquer it happened until 1524. In the first 20 years of the 1500s, Spain took control of the Caribbean Sea islands. They used these islands to launch attacks on the mainland of the Americas. From Hispaniola, they reached Puerto Rico in 1508, Jamaica in 1509, Cuba in 1511, and Florida in 1513.

The Spanish heard rumors of the rich Aztec empire in Mexico. In 1519, Hernán Cortés sailed to explore the Mexican coast. By August 1521, the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, had fallen to the Spanish. The Spanish conquered much of Mexico within three years. This new land became New Spain. It was led by a viceroy who reported to the Spanish Crown.

The conquest of Central America was like an extension of the Aztec campaign. Cortés himself helped conquer Honduras in 1524–1525. In the 20 years between finding Honduras and trying to colonize it, the Spanish also settled in Castilla de Oro. From there, expeditions were launched north. These included famous conquerors like Pedrarias Dávila and Gil González Dávila.

In 1508, Spanish sailors briefly explored the Caribbean coast of Honduras. But their main focus was further north. In the 1510s, expeditions from Cuba and Hispaniola reported that the Bay Islands were inhabited. The first attempts to conquer Honduras came from different Spanish areas. These included Hispaniola, Mexico, and Panama. This led to arguments over who had the right to control the land. These arguments slowed down the conquest.

Spanish Soldiers and Their Ways

The Spanish conquerors, called conquistadors, were all volunteers. Most of them did not get a regular salary. Instead, they received a share of what they won. This included precious metals, land, and native workers. Many Spanish soldiers had already fought in Europe.

In the 1500s, Spanish conquistadors used broadswords, rapiers, crossbows, and early guns called matchlocks. They also had light artillery. Soldiers on horseback used a 3.7-meter (12-foot) long lance. This could also be used by foot soldiers as a pike. They also used different types of halberds and bills. Besides the one-handed broadsword, a longer, two-handed version (1.7 meters or 5.5 feet) was also used.

Crossbows had 0.6-meter (2-foot) arms made of strong wood, horn, bone, and cane. They had a stirrup to help pull the string with a crank. Crossbows were easier to keep working than matchlocks. This was especially true in the hot, wet climate of the Caribbean region.

Metal armor was not very useful in the hot, wet climate. It was heavy and rusted easily. In direct sunlight, it became too hot to wear. Conquerors often did not wear metal armor. Or they only put it on right before a battle. They quickly started using quilted cotton armor. This was like the armor used by the native people they fought. They often wore this with a simple metal war hat. Shields were very important for both foot soldiers and cavalry. These were usually round, convex shields made of iron or wood. Rings held them to the arm and hand.

The Encomienda System

Honduras was not a rich province. It did not attract the most famous conquerors. Most conquerors and settlers who came to Honduras wanted to get rich quickly. They hoped to return to Spain with wealth and a higher social status. So, they looked for quick ways to get rich.

The conquest was based on giving out encomienda rights and land. An encomienda gave the encomendero (the person who held it) the right to get tribute and labor from native people in a certain area. Until the mid-1500s, the encomendero could decide how much tribute and labor the natives had to provide. This led to a lot of abuse.

The encomiendas in Honduras were small. They did not make money quickly. People gained social status by controlling natives through this system. In Honduras, conquerors made money by selling natives into slavery. They sold them to the Caribbean Islands and Panama. They also made money from mining. This led to a big drop in the native population in Honduras. Economic production also fell sharply in the first half of the 1500s. Overall, Spanish colonists did not want to invest time or money in developing farms on their encomiendas in Honduras.

The Spanish built colonial towns to spread their power. These towns also served as administrative centers. They preferred to build towns where many native people lived. Or near places with easily found minerals. Many Spanish towns were built near older native towns. Trujillo was founded near the native town of Guaimura. Comayagua was built on an existing town of the same name.

In the first half of the 1500s, towns were often abandoned or moved. This happened for many reasons. These included native attacks, harsh conditions, and diseases from the Old World. Diseases like smallpox, measles, typhoid, yellow fever, and malaria killed many people. Sometimes, towns were moved for political reasons. Spanish groups fought among themselves. Those in power would try to undo what others had done. Moving towns and changing encomiendas often made things unstable. This slowed down the conquest.

How the Colony Was Organized

The Spanish made Comayagua an important administrative center. It was one of four main gobiernos (governments) in Central America. It was important for trade and industry. Less important centers, like Tegucigalpa, were called alcaldías mayores. Areas with fewer settlers were called corregimientos. A corregimiento included several native villages, called pueblos de indios.

A Spanish corregidor governed the corregimiento. But the Spanish also appointed native officials. These included the alcalde (mayor) and his regidores (councillors). All levels of colonial government focused on collecting tribute and organizing native labor.

In 1544, the Spanish set up the Audiencia de los Confines in Gracias a Dios. This location in western Honduras was chosen because it was central in Central America. It was also a mining center with many native people. The Audiencia became the main administrative center. It governed Honduras, Chiapas, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Panama, Tabasco, and Yucatán.

Native Weapons and Fighting Styles

Native warriors mainly used arrows or darts with obsidian points. They also used spears and wooden swords with sharp stone edges. These were similar to the Aztec macuahuitl. They also used stone knives and slings.

When the Spanish attacked, native communities built strong defenses. They used palisades (fences of heavy wood) and ditches. The palisades had openings for shooting arrows. They also built towers and dug hidden pits around the walls for defense. Building fortified settlements was not common in Honduras before the Spanish arrived. But fortifications were known from contact with Maya groups to the west.

In Honduras, these forts were built quickly to fight the Spanish. The forts at the Maya town of Ticamaya in the Ulúa Valley were so strong that they stopped several Spanish attacks. The Spanish thought the Lenca fort at the Peñol de Cerquín was as strong as any they had seen in Europe. When attacked in their mountain strongholds, natives would roll large rocks down the mountainside onto the attackers. If natives knew the Spanish were coming to fight, they often left their villages and fled to hard-to-reach areas.

Discovery of Honduras

On July 30, 1502, during his fourth voyage, Christopher Columbus reached Guanaja. This is one of the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras. He sent his brother, Bartholomew, to explore the island. As Bartholomew explored, a large canoe approached. It was carved from one tree trunk and had 25 rowers.

Bartholomew Columbus boarded the canoe. He found it was a Maya trading canoe from Yucatán. It carried well-dressed Maya people and rich goods. These included pottery, cotton cloth, stone axes, war clubs with flint, copper axes and bells, and cacao beans. There were also some women and children, likely to be sold as slaves. The Europeans took what they wanted and captured the elderly Maya captain to be an interpreter. The canoe was then allowed to leave. News of these pirate-like strangers likely spread along the Maya trade routes.

A few days later, on August 14, 1502, Columbus arrived on the mainland of Honduras. He anchored at a place he called Punta Caxinas. This is now known as the Cape of Honduras, near modern Trujillo. He claimed the land for the king of Spain. The people living on the coast were friendly to him. After this, he sailed east along the coast. He fought gales and storms for a month. Then the coast turned south, and he entered calmer waters. The Spanish named this point Cabo Gracias a Dios, meaning "Cape Thanks to God," because they were free from the storms. Columbus sailed south to Panama. Then he turned back into the Caribbean Sea. His ship was wrecked off Jamaica. He was rescued and taken to Hispaniola, and from there, he returned to Spain.

First Spanish Expeditions

The first 40 years of the conquest were very chaotic. Spain did not fully control Honduras until 1539. The first Spanish settlements were Trujillo, Gracias a Dios, and areas around Comayagua and San Pedro. Unlike in Mexico, where a strong native empire could be overthrown quickly, Honduras had no single power to conquer. This made it harder to take over the land for the Spanish Empire. Sometimes, the Spanish would conquer an area and move on, only for the natives to rebel or kill the Spanish settlers.

Early Spanish efforts focused on building a presence along the Caribbean coast. They founded settlements like Buena Esperanza, San Gil de Buena Vista, Triunfo de la Cruz, and Trujillo. Soon after, expeditions started moving inland. They faced strong native resistance. In 1522, the natives of the Olancho Valley rebelled and killed the Spanish forces there.

Fighting among the Spanish also slowed down the conquest. In 1522, Gil González Dávila and Andrés Niño sailed from Panama along the Pacific coast. They explored the south coast of what would become Honduras. They entered the Gulf of Fonseca. When they returned to Panama, the governor, Pedro Arias Dávila (Pedrarias Dávila), claimed the land they had explored. While Gil González Dávila was in Santo Domingo planning a new trip, Pedrarias Dávila sent Francisco Hernández de Córdoba to take control of the region. Spanish settlements in Nicaragua were mostly along the Pacific coast. Honduras was seen as a better way to reach the Caribbean and Spain. This caused fights over who had authority between the two provinces.

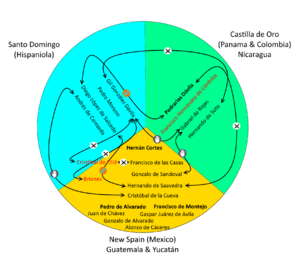

Rival Spanish Groups in the 1520s

A year after Gil González Dávila found the Gulf of Fonseca, several Spanish expeditions tried to conquer Honduras. These groups came from Mexico and Guatemala (southwards), and from Panama and Nicaragua (northwards). Their leaders fought each other in Honduras. So, the conquest of the natives was often interrupted by battles between rival Spanish forces. Even within Spanish groups, there was infighting. The different Spanish groups also used native allies to help them.

In 1523, Hernán Cortés sent two expeditions from Mexico towards Central America. One went by land, led by Pedro de Alvarado. The other went by sea, led by Cristóbal de Olid. Alvarado started the conquest of Guatemala, then went into Honduras. Olid began conquering Honduras' interior in 1524. But he soon decided to become independent from Cortés.

Gil González Dávila's Trip from Hispaniola, 1524

Gil González Dávila left Santo Domingo in early 1524. He wanted to explore the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua. His journey took him to the north coast of Honduras. A storm hit his ships. To make them lighter, he ordered some horses to be thrown overboard. Because of this, the place was named Puerto de Caballos ("Port of Horses").

González Dávila landed on the north coast. He had permission from the king to conquer Honduras. He had already sent a large sum of gold (112,524 castellanos) to the king from his campaigns in Panama and Nicaragua. Puerto de Caballos later became an important base for colonizing the region.

From Puerto de Caballos, Gil González sailed west to the Amatique Bay. He founded a Spanish settlement called San Gil de Buena Vista. This was near the mouth of the Río Dulce, in modern Guatemala. He then started a conquest campaign in the mountains between Honduras and Guatemala. González left some men under Francisco Riquelme at San Gil de Buena Vista. He then sailed back east along the coast, past the Cape of Honduras. From there, he marched inland to find a way to the Pacific Ocean. The settlers at San Gil de Buena Vista did not do well. They soon moved to a more suitable place. They resettled in the important native town of Nito, near the mouth of the Dulce River.

Cristóbal de Olid's Trip from Mexico, 1524

Cristóbal de Olid sailed from Mexico in January 1524. He stopped in Cuba to pick up supplies from Hernán Cortés. But the governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez, was an enemy of Cortés. He convinced Olid to take Honduras for himself.

Olid arrived off northern Honduras in early May, east of Puerto de Caballos. He landed with 360 Spanish soldiers and 22 horses. He founded Triunfo de la Cruz, which still has that name today, near the modern port of Tela. He claimed the new land in Cortés's name. But after founding the town, he openly turned against Cortés. Most of his men supported him. He then started conquering western Honduras. He took over the heavily populated towns of Naco and Tencoa, which did not resist much.

The Fight for Honduras

Now, four people claimed to control Honduras. Gil González Dávila had royal permission. Pedrarias Dávila claimed it because of his expeditions. Hernán Cortés claimed it because of Olid's expedition. And Olid himself claimed it. A fifth claimant, the Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo, also tried to take direct control. These rival claims led to betrayal, conflict, and even civil war among the Spanish groups.

Cortés heard about Olid's rebellion and his fight with González. He sent his cousin, Francisco de las Casas, to bring the rival captains back in line. Cortés believed most of Olid's men would join Las Casas. So, he only gave Las Casas about 150 men. Las Casas arrived off Triunfo de la Cruz as Olid was getting ready to attack Gil González Dávila. González was in the Naco valley.

González and Olid had an uneasy agreement. Neither wanted to fight openly. But Olid had more men than González. González had also made a mistake by splitting his forces. He left most of his men by the Dulce River. Olid sent one of his captains, Pedro de Briones, to attack part of González's forces. Olid also prepared his ships to sail along the coast and attack other groups. Briones quickly weakened González's position and captured about half of his men. At this point, Las Casas's fleet appeared off the coast.

Olid tried to stop Las Casas from landing. He quickly sent a message to recall Briones. The two Spanish fleets started firing at each other. Olid tried to negotiate a truce to delay Las Casas until Briones returned. Las Casas secretly sent messages to Briones, trying to get him to join against Olid. Briones, looking out for himself, delayed his return. Then, Las Casas's fleet was caught in a sudden storm. It was wrecked on the Honduran coast, killing some of Las Casas's men. Olid captured the survivors.

Olid then marched inland to the Naco Valley. One of his captains surprised González Dávila and his men. They were marched under guard back to Naco and imprisoned. Now that Olid was in control, Briones feared his revenge for not helping him. So, Briones pledged loyalty to Hernán Cortés. Olid imprisoned Las Casas in Naco with González.

Olid sent Briones to conquer more land. Instead, Briones marched towards New Spain with his forces. He arrived in the Guatemalan Highlands in early 1525. His men helped Pedro de Alvarado fight the highland Maya. In 1525, the Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo, based in Hispaniola, sent Pedro Moreno to Honduras. He was to try and settle the dispute between Olid and González.

The Death of Cristóbal de Olid

Olid treated González and Las Casas more like honored guests than prisoners. Pedro de Briones leaving Honduras greatly weakened Olid's forces. Las Casas and González Dávila used this chance. They took advantage of Olid's trust to attack him and escape. Once free, they expected help from Briones.

One evening, González and Las Casas attacked Olid and badly wounded him. Olid managed to escape and hid in a native hut. But he was quickly found and put on a quick trial. Olid was executed by having his throat cut in the plaza at Naco. After Olid's death, Spanish relations with the natives of Naco got much worse. The natives did not want to give the Spanish food or supplies. Most of the Spanish left the settlement. They either went back to Mexico or moved to other parts of Honduras. A court in Mexico later said Las Casas and González Dávila were guilty of executing Olid. But neither was ever punished.

Founding of Trujillo, 1525

After Olid's death, Las Casas declared Cortés's control over the colony. The Spanish who stayed in Honduras split into groups. Most stayed under Francisco de las Casas. Las Casas thought the harbor at Triunfo de la Cruz was not good enough. So, he planned to move it to Puerto de Caballos. Las Casas was eager to return to New Spain. So, he gave command of the province to Juan López de Aguirre. He told him to move the port. Las Casas returned to Mexico by way of the Pacific coast of Guatemala. He took Gil González with him. He found Pedro de Briones in Guatemala and had him hanged as a traitor.

López de Aguirre did not like Puerto de Caballos for the new town. Instead, he sailed east with half of his men to the Cape of Honduras. This was near where Columbus had first landed. The rest of his people followed east on foot. López de Aguirre did not wait for them. He sailed away, abandoning Honduras. When the land party arrived, they were troubled by López de Aguirre's desertion. But they settled in Trujillo as planned. The town was founded in May 1525. It was in the largest sheltered bay on the Caribbean coast of Central America.

Pedro Moreno, sent from the Audiencia of Santo Domingo in Hispaniola, arrived in Honduras soon after Trujillo was founded. He found 40 settlers in a bad state, lacking weapons and supplies. A few more Spaniards were still at Nito, the remaining men of González Dávila. Their situation was even worse. The people of Trujillo begged Moreno for help. He agreed, but only if they rejected Cortés. They had to accept the authority of the Audiencia of Santo Domingo. And they had to accept Juan Ruano, one of Olid's former officers, as Chief Magistrate. Moreno renamed Trujillo as Ascensión. He sent messages to Hernández de Córdoba in Nicaragua. He asked him to stop being loyal to Pedrarias Dávila and pledge loyalty to Santo Domingo. Moreno then returned to Hispaniola, promising to send help. As soon as he was gone, the residents changed the name back to Trujillo. They pledged their loyalty to Cortés again and expelled Juan Ruano.

Hernán Cortés in Honduras, 1525–1526

Hernán Cortés only received occasional updates about what was happening in Honduras. He grew impatient for it to be part of his command. Hoping to find new riches, he decided to travel to Honduras himself. Cortés left Tenochtitlan on October 12, 1524. He had 140 Spanish soldiers, 93 of them on horseback. He also had 3,000 Mexican warriors, 150 horses, pigs, artillery, and supplies. Along the way, he recruited 600 Chontal Maya carriers.

During the difficult journey from Lake Petén Itzá to Lake Izabal (both now in Guatemala), Cortés lost many men and horses. He crossed the Dulce River to Nito. This settlement was somewhere on the Amatique Bay. He arrived with about a dozen companions. There, he found the starving remains of Gil González Dávila's settlers. They were happy to see him. Cortés waited there for his army to regroup for a week. He explored the area for supplies. By this time, only a few hundred men were left from Cortés's expedition.

Cortés sent some of González Dávila's settlers south to the Naco Valley. This area was quickly brought under control by Gonzalo de Sandoval, one of Cortés's officers. Cortés then gave up on colonizing Nito. He sailed to Puerto de Caballos with all his remaining men.

Cortés arrived in Honduras in 1525, bringing livestock. He claimed control over Honduras, though its exact size was still unknown. He quickly took charge of the rival Spanish groups and some native groups. He founded a settlement called Natividad de Nuestra Señora near Puerto de Caballos. He settled 50 colonists there and put Diego de Godoy in charge. Cortés then sailed to Trujillo. Conditions in Natividad were unhealthy. Half of the Spanish settlers quickly died from disease. With Cortés's permission, the rest moved inland to the fertile Naco Valley. Sandoval had already established a strong Spanish presence there.

Cortés found things in Trujillo to be good since Moreno left. He sent letters to Santo Domingo to get them to recognize his control over the colony. He sent ships to Cuba and Jamaica for supplies. These included animals and plants for farming. Cortés sent his cousin Hernando de Saavedra inland. Saavedra overcame local resistance and brought several well-populated areas under Spanish control. Native leaders came from far away to pledge loyalty to Cortés. They thought he was fairer than other Spanish captains. With diplomacy, fair treatment of natives, and smart use of force, Cortés strengthened Spanish control over Honduras.

Taking Control of the Northern Nahuas

While in Trujillo, Cortés received messages from Papayeca. This was a large native town about 29 kilometers (18 miles) away. He also heard from Champagua (now Chapagua), another nearby town. Both towns were home to Nahuas. Cortés wrote down the names of two Nahua rulers: Pizacura and Mazatl.

Pizacura resisted Cortés and refused to swear loyalty. Cortés sent Spanish cavalry and foot soldiers. They were joined by many native allies. They attacked Pizacura's village in the Agalta Valley at night. They captured the Nahua leader and a hundred of his people. Most were enslaved. Pizacura was held prisoner with two other nobles and a young man. Cortés suspected the young man was the true leader. Pizacura claimed Mazatl had caused his resistance. Mazatl opposed peace with the Spanish. Cortés captured Mazatl and asked him to order his people to return to their empty villages. Mazatl refused, so Cortés hanged him in Trujillo.

Gabriel de Rojas and Gonzalo de Sandoval in Olancho

Gabriel de Rojas was still in Olancho. Native people told him about new Spanish arrivals in Trujillo. He sent a letter and gifts with messengers. They met Gonzalo de Sandoval, who was taking control of Papayeca at the time. Then they went on to Cortés in Trujillo. Cortés at first responded in a friendly way to Rojas.

Rojas's group was trying to expand Hernández de Córdoba's territory in Nicaragua. When they met native resistance, his men started stealing and enslaving the people. Natives complained to Cortés. Cortés sent Sandoval with ten cavalry to give Rojas papers. These ordered him out of the territory. They also told him to release any natives and their goods he had taken. Sandoval was ordered to either capture Rojas or expel him from Honduras. But he could not do either because other Spaniards present tried to calm the situation.

While the two groups were still together, Rojas received orders from Francisco Hernández de Córdoba. He was told to return to Nicaragua to help him against his rebellious captains. Sandoval returned to face Cortés's anger.

Hernández de Córdoba sent a second expedition into Honduras. They carried letters to the Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo and to the Crown. They were looking for a good port on the Caribbean coast to link to Nicaragua. Sandoval stopped and captured this expedition. He sent some of the Nicaraguan group back to Cortés in Trujillo. They told Cortés about Hernández de Córdoba's plan to become independent from Pedrarias Dávila in Panama. Cortés was polite and offered supplies. But he sent letters advising Hernández de Córdoba to stay loyal to Pedrarias Dávila.

Hernando de Saavedra

Hernán Cortés was worried that his enemies in New Spain were taking control of Mexico. When Cortés heard that Pedro Moreno would soon arrive in Honduras with many settlers and official documents from the Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo, he decided not to explore further. Instead, he returned to Mexico, leaving on April 26, 1526. He took Pizacura to Mexico with him, where he died soon after from an illness. Gonzalo de Sandoval also returned to Mexico, marching overland through Guatemala.

Cortés made his cousin Hernando de Saavedra governor of the new territory. He told Saavedra to treat the natives fairly. However, Saavedra's actions reopened old arguments between rival groups of settlers. Saavedra quickly took control of what is now the department of Olancho. He sent Bartolomé de Celada inland to find a good place for a new Spanish town. He founded Frontera de Cáceras on the savannah of the Olancho valley. This was near the native towns of Telica and Escamilpa, in the disputed area between Honduras and Nicaragua.

Meanwhile, Pedrarias Dávila traveled to Nicaragua from Panama. He executed Hernández de Córdoba and took direct control of the province. He claimed Honduras for himself. He sent several expeditions into the Olancho Valley. Saavedra demanded that Pedrarias Dávila leave. Dávila sent friendly messages back. But then, Dávila launched a surprise attack against Cortés's supporters. He captured some of them in Olancho. Then he marched north to attack Puerto de Caballos.

Saavedra heard about the attack and sent a larger force to stop Pedrarias Dávila's captains. After talking, both forces agreed to retreat. But Dávila's force broke the agreement and split into two. One part continued towards Puerto de Caballos. The other returned to Olancho to found a settlement and hold the valley for Pedrarias Dávila.

Pedraria Dávila's forces in the Olancho valley treated the natives harshly. This caused the natives to rebel throughout the province. They attacked the new settlement and killed many Spaniards, including their leader. The Spanish survivors fled and found safety with a native leader who had not joined the revolt. Natives in the north launched a huge attack on Natividad de Nuesta Señora near Puerto Caballos. This forced the Spanish there to hide in a natural stronghold. They sent a request for help to Saavedra, who could not spare any men. Pedrarias Dávila's men who were marching to attack Puerto de Caballos turned back to Olancho. They found the Spanish settlement there had been destroyed. They found refuge with the survivors to keep a weak presence in support of Pedrarias Dávila's claim over Honduras.

Hernando de Saavedra protested against Pedrarias Dávila's actions. But he thought his own forces were too small to attack Dávila's men in Olancho. Dávila, in turn, sent messengers to demand that Saavedra and the town council of Trujillo obey him. The Spanish Crown was now paying close attention to the chaotic situation in Central America. It was trying to appoint Crown officials as governors. It was also creating colonial organizations like the audiencias (courts). These were meant to impose absolute government over lands claimed by Spain. This ended the time when famous conquerors could set themselves up as rulers of the lands they conquered. On August 30, 1526, Diego López de Salcedo was appointed governor of Honduras by the Crown. He left Santo Domingo in early September. The Audiencia ordered all rival claimants out of the colony.

Crown Takes Control, 1526–1530

Diego López de Salcedo sailed from Santo Domingo with two ships. He carried many soldiers, as well as supplies and clothes to sell to the colonists. Bad winds delayed López de Salcedo off Jamaica for a month. He finally landed in Trujillo on October 26, 1526. This was after a long standoff with Hernando de Saavedra that almost led to a fight. At last, Saavedra was convinced that López de Salcedo had been authorized directly by the Crown. He allowed him to come ashore.

López de Salcedo was ordered to investigate the problems in the province. He was to take any actions needed to bring order. But he and the governors after him put their own goals ahead of good government. This caused division among the colonists. They also treated the native population very harshly. In 1527, the natives rebelled against this cruel treatment. The punishment given to the rebellious natives only caused more revolts. López de Salcedo arrested Saavedra and his supporters. He sent them to Santo Domingo to be tried by the Real Audiencia. But the prisoners took control of the ship and sailed to Cuba.

After López de Salcedo became governor, messengers from Pedrarias Dávila arrived. They expected to find Saavedra. They did not dare to present Dávila's demands to a Crown representative. But López de Salcedo had them imprisoned. When the Crown appointed the new governor, it had not defined the borders of Honduras. Pedrarias Dávila had been replaced by a Crown representative in July 1526. This led López de Salcedo to claim control over Nicaragua. He based this on the actions of Gil González Dávila and Hernán Cortés. He left a few men under Francisco de Cisneros in Trujillo. He then marched with 150 men to take control of Nicaragua.

Native Unrest, 1528

López de Salcedo moved Trujillo to a higher, drier spot. In 1528, López de Salcedo spent a month in the Olancho Valley. This area was likely inhabited by Pech people at the time. He tried to control the people there. This made them ready to fight against more Spanish attacks. He hanged several native leaders who had attacked Natividad de Nuestra Señora. He also put such harsh demands on the natives that they burned their villages and crops and fled into the mountains.

In Olancho, López de Salcedo unsuccessfully fought with rival Spaniards he found there. Unrest among the natives spread widely. It went from Comayagua as far south as Nicaragua. This made it hard to get supplies. It also created constant danger for the expedition. Nevertheless, he continued to León, in Nicaragua. Around this time, Pedrarias Dávila was appointed governor of Nicaragua. He had strongly protested losing his governorship over Castilla del Oro.

While López de Salcedo was in Nicaragua, Francisco de Cisneros could not control Trujillo. Its citizens soon removed him from power. López de Salcedo sent messages appointing Diego Méndez de Hinostrosa as his lieutenant. But his opponents imprisoned the new appointee. They replaced him with Vasco de Herrera, one of Trujillo's town councillors. Vasco de Herrera sent an expedition into the Olancho Valley to conquer the natives. They harassed the local people and enslaved many.

First Governor's Imprisonment and Death, 1528–1530

Pedrarias Dávila traveled from Panama to take command of Nicaragua. He was welcomed everywhere as the rightful governor. López de Salcedo tried to leave the province and return to Honduras. But his rival's supporters stopped him. Pedrarias Dávila arrested López de Salcedo in March 1528. He forced him to give up some of his territory. The Spanish king later rejected this agreement. Dávila kept López de Salcedo prisoner for almost a year. He released him after reaching an agreement with mediators. This agreement defined the borders of Honduras. It included the Caribbean coast from Puerto de Caballos in the west to Cabo Gracias a Dios in the east. It extended inland in a triangle shape. This agreement settled all border disputes with Nicaragua. But border disputes with Guatemala remained a problem.

López de Salcedo returned to Honduras in early 1529 as a broken man. He could not settle the dispute between Diego Méndez de Hinostrosa and Vasco de Herrera. Many people in Trujillo looked down on him. To fix his reputation, he organized a large expedition to settle the Naco valley. Gold had been found there. López de Salcedo, weakened by his troubles, did not live to lead the expedition. He died in early 1530.

Ch'orti' Resistance, 1530–1531

During the conquest, Q'alel was a ruler of the Ch'orti' Maya in what is now western Honduras. Q'alel was the lord of Copán, a town near modern Rincón del Jicaque. This is not the famous archaeological site. Q'alel fortified Copán with a strong wooden fence and a moat. He gathered an army of 30,000 warriors to drive out the Spanish.

The Spanish attack came from Guatemala. This was after Ch'orti' attacks on Spanish settlers there. In early 1530, Pedro de Alvarado sent Spanish troops with native allies. They were led by Hernando de Chávez, Jorge de Bocanegra, and Pedro Amalín. Q'alel refused to surrender. The Ch'orti' forts were strong enough to hold off the Spanish for several days. But eventually, the Spanish crossed the moat and broke through the fence. They defeated the defenders. Ch'orti' resistance was crushed by the next year. Most of the fighting was over by April 1531.

Chaos in the Colony

After 1530, the colonists themselves held the power. They installed new governors and removed them. By 1534, the Spanish colony in Honduras was almost falling apart. Trujillo had fewer than 200 people. It was the only Spanish settlement in Honduras. Very little land beyond the town itself had been conquered. The Spanish were fighting among themselves. They had also caused widespread native uprisings. At the same time, the native population had dropped sharply. This was due to disease, bad treatment, and many being sold as slaves to work on sugar plantations in the Caribbean islands.

Before he died, López Salcedo appointed Andrés de Cerezeda as his successor. Cerezeda could not control the people of Trujillo. Two rivals fought for power. Vasco de Herrera was supported by the town council. He was strong enough to force Cerezeda to share power. In reality, Vasco de Herrera held the true power.

The expedition to the Valley of Naco, planned by López de Salcedo before he died, reached its goal. They founded a new settlement called Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación. At the same time, Spanish captain Alonso Ortiz calmed the restless natives near Trujillo. At first, the natives fled. But he convinced them to return home.

The fighting between rival Spanish groups in Trujillo continued. Vasco de Herrera could not unite the colonists. He decided the best option was to found a new town. He even thought about abandoning Trujillo. Cerezeda opposed him, believing this would ruin the Spanish effort in Honduras. Natives working in the mines near Trujillo rebelled against high taxes. They killed several Spaniards. Vasco de Herrera used this as an excuse to launch an attack. But instead, he marched inland to try and found another colony. The Nahuas of Papayeca rebelled against Andrés de Cereceda's cruelty. They fled into the wilderness. In 1531, Vasco de Herrera tried to bring them back to their settlements.

Deaths of Vasco de Herrera and Méndez de Hinostrosa

Cerezeda left Trujillo for a short time. With Vasco de Herrera also gone, Méndez de Hinostrosa tried to take sole power. Vasco de Herrera eventually returned. But he had left many of his soldiers fighting native resistance in the Olancho Valley. This resistance was led by his brother, Diego Díaz de Herrera. Vasco de Herrera ordered Méndez de Hinostrosa to be executed. But he found safety in a church. His supporters soon gathered, outnumbering Vasco de Herrera's men in Trujillo.

Cerezeda returned to Trujillo and tried to mediate between the groups. But Vasco de Herrera was killed. Méndez de Hinostrosa took control of the town. Cerezeda refused to recognize him. Both sides sent urgent messages to Diego Díaz de Herrera in Olancho, asking for his support. Many of his men supported Méndez de Hinostrosa. Cerezeda acted quickly. Fierce fighting broke out in Trujillo. Cerezeda captured Méndez de Hinostrosa and beheaded him. Finally, after a year of Spanish infighting, Cerezeda became the sole governor of Honduras.

New Spanish Arrivals, 1532–1533

The Crown heard about the chaos in Honduras. They named the elderly Diego Alvítez as the royal governor. Alvítez's fleet was wrecked a few leagues from Trujillo in late October 1532. He finished his journey on foot. By the time he reached the capital, soon after Cerezeda took sole charge, he was near death. On November 2, he named Cerezeda as acting governor and died soon after.

Opposing groups formed again. One was led by Diego Díaz de Herrera. Cerezeda held onto power with great difficulty. To stabilize the province, he organized another expedition to settle the Naco valley. He sent a captain with 60 soldiers south. He planned to follow with more men. But he was delayed in Trujillo by reports of a Spanish expedition coming along the coast from the west.

The new arrivals were led by Alonso d' Ávila. He was an officer of Francisco de Montejo, who had been named adelantado (military governor) of Yucatán. Ávila had tried to build a Spanish town on the east side of the Yucatán Peninsula. But native resistance had forced him out. Since the whole region was at war with the Spanish, Ávila could not return to Montejo. Instead, he traveled along the Caribbean coast in canoes, looking for a good place for a new settlement. By the time he reached Puerto de Caballos, his expedition was in danger. Ávila asked Cerezeda for help. Cerezeda sent supplies to the struggling group. Ávila and his men finally arrived in Trujillo in early 1533.

Ávila planned to build a settlement in Montejo's name near Puerto de Caballos. But he knew it was in Honduras's territory. And Cerezeda would never support it. In any case, the situation in Trujillo was too unstable for Cerezeda to support a major expedition. Ávila got involved in the town's political fights, supporting Diego Díaz de Herrera. After a while, he decided to leave Honduras. He and most of his men took passage on a ship that stopped at Trujillo. It took them back to Yucatán. A few of Ávila's men stayed and settled in Trujillo, where the situation continued to get worse.

Honduras-Higueras and Conquest Licenses

In 1532, Pedro de Alvarado, governor of Guatemala, received royal permission to conquer the area of Higueras. This was to establish a Caribbean port for Guatemala. Less than a year later, Diego Alvítez, then governor of Honduras and Higueras, also got royal permission. He was to pacify and colonize the Naco valley and the area around Puerto de Caballos.

Soon after, in 1533, Francisco de Montejo, governor of Yucatán, was granted governorship over a huge area. This stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Ulúa River, Naco, and Puerto de Caballos. This was allowed as long as Alvarado or Alvítez had not already settled those regions. At the same time, Alvarado's permission to conquer parts of Higueras was reconfirmed. This meant all three governors had royal permission to conquer and settle the same general region. They could interpret the royal orders as they chose.

In 1534, the Spanish Crown reorganized Honduras. It became the Provincia de Higueras e Cabo de Honduras ("Province of Higueras and Cape of Honduras"). The western part, from the Golfo Dulce (now in Guatemala) to the Ulúa Valley and Naco, was called Higueras. The eastern part was Honduras. This included Trujillo, the Valley of Olancho, and extended to Cape Camarón. Although organized as two territories, it was effectively one province, often called Honduras-Higueras. In 1534, Honduras-Higueras was removed from the control of New Spain. It had been under New Spain since the late 1520s. It was returned to the control of the Audiencia of Santo Domingo.

Cerezeda Moves to Higueras, 1534

Cerezeda finally set out with his expedition to the interior. But he was forced to return when Díaz de Herrera tried to abandon Trujillo. He wanted to take all the colonists with him. Trujillo was now on the verge of collapse. The Spanish lacked essential supplies. Even though more Spanish soldiers had come to Honduras than were needed to conquer Peru, the bitter Spanish infighting had almost completely destroyed the colony.

Trujillo was the only Spanish settlement left. It had fewer than 200 Spanish inhabitants. The Spanish attacks on the native population had caused great harm. But they failed to conquer any land outside Trujillo's immediate area. The native population dropped sharply. Many natives were sold as slaves to work on Caribbean island plantations. In 1533, an epidemic swept through the natives in the Spanish-controlled area, killing half of them. The encomienda system was not working well. There was little tribute, and no rich silver or gold mines. Many colonists had heard about the riches in Peru. They threatened to leave. By 1534, the only richly populated native region left was the Naco valley. In desperation, Cerezeda again planned to move the colony west to Naco.

In March 1534, Cerezeda left 50 Spaniards in Trujillo. He took most of his men, about 130, on his expedition into Higueras. He sent 60 mixed cavalry and infantry overland, driving livestock. Cerezeda traveled by sea with the rest. The two groups met at Naco, where they settled for some time. Eventually, a lack of supplies forced them to move on. So, they moved to the Sula Valley, inhabited by Maya. There they founded Villa de Buena Esperanza ("Town of Good Hope"). The new settlement was 23 leagues (about 97 km or 60 miles) from Puerto de Caballos. It was seven leagues (about 29 km or 18 miles) from Naco. And it was three leagues (about 13 km or 8 miles) from the Maya town of Quimistan. Cerezeda sent scouting parties into the surrounding countryside to conquer the natives and search for precious metals. This westward push by Cerezeda shifted the focus of the Spanish colony from Trujillo to Higueras.

Cristóbal de la Cueva's Arrival from Guatemala

At the same time Cerezeda was setting up a new base in the west, Cristóbal de la Cueva entered Honduras from Guatemala with 40 men. He was under orders from Jorge de Alvarado, Pedro de Alvarado's brother. Jorge was acting as governor while Pedro was fighting in Ecuador. De la Cueva was looking for a good Caribbean port and a road connecting it to Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala.

Cerezeda met the Guatemalan captain. They made a deal: Cerezeda would take command of de la Cueva's soldiers. They would help him explore and conquer the area around Buena Esperanza. In return, Cerezeda would establish the port and road inland to Santiago de Guatemala. The original plan was to reestablish either Puerto de Caballos or San Gil de Buena Vista. But de la Cueva changed his mind. He argued for a new inland colony, which Cerezeda opposed. De la Cueva's men became rebellious and refused to obey Cerezeda. De la Cueva left Higueras and marched south to reinforce San Miguel (in modern El Salvador), near the Gulf of Fonseca. This brought San Miguel under Guatemala's control. Cerezeda believed it was part of Honduras-Higueras and strongly protested to the Crown. Control over San Miguel remained a point of conflict between Honduras and Guatemala for years.

Cerezeda divided the land around Buena Esperanza among his men using the encomienda system. Gold and silver were found, which made the colonists happy. Cerezeda planned to develop Buena Esperanza as a trade center. It would link a route from the Caribbean and Spain to the Pacific and the wealth of recently conquered Peru. The route would involve resettling Puerto de Caballos. It was planned to pass through the native settlement of Maniani, which Cerezeda wanted to develop as a trading center, and then on to the Gulf of Fonseca.

Sicumba, Lord of Ulúa Valley

In the mid-1530s, the natives of western Honduras fought against the Spanish. Their efforts were led by Sicumba in the Ulúa Valley. Sicumba was the native lord of a large, well-populated area along the lower Ulúa River. He had several strong forts along the river. He commanded many warriors. His main base was his riverside fort at Ticamaya. Sicumba led a native campaign that successfully limited Spanish activities in western Honduras for ten years.

Writing to the king of Spain in late August 1535, Andrés de Cerezeda reported that Sicumba had attacked Puerto de Caballos. He had killed several Spaniards there. The Spanish wife of one of the dead men was captured by the natives. Sicumba took her as his woman. Cerezeda attacked Sicumba while Cristóbal de la Cueva was still in Higueras. He won a victory. But Sicumba started fighting again as soon as the Spanish left his territory. He began to organize native resistance against the Spanish attacks.

Decline of Higueras-Honduras

After Andrés de Cerezeda took most of the people from Trujillo to Higueras, the city began to decline. The people who stayed were too old, sick, or discouraged to go west. Basic supplies like food and clothing were hard to find. The citizens believed Cerezeda wanted to abandon Trujillo. They asked the Audiencia of Santo Domingo and the Crown for supplies and a Crown-appointed governor.

In Higueras, Cerezeda became ill. He could not provide strong leadership. He was unable to expand the conquered area. The Spanish treated the native people very harshly. This caused the population to drop. Many natives either died from the cruel treatment or fled to the hills. The natives who remained were increasingly hostile. They refused to work for their encomendero overlords. This resistance grew stronger around Sicumba. More and more native warriors joined him. Areas that had been partly conquered rose up against the Spanish.

Areas that had been taken by the Spanish were lost. The Spanish were surrounded in a small area around Buena Esperanza. The colonists were losing hope. They feared a huge native attack at any moment. They were also desperately short of supplies because the encomienda towns refused to provide them. The colonists openly questioned Cerezeda's leadership. New groups formed, with treasurer Diego García de Solís leading the opposition. Rumors of the riches in Peru drew Spaniards away from the struggling colony in Honduras-Higueras. Forty or fifty men left to find better fortune elsewhere. Although precious metals had been found near Buena Esperanza, it was impossible to mine them due to the natives' hostility. Despite Cerezeda's opposition, García de Solís appealed directly to the governor of Guatemala, Pedro de Alvarado. Alvarado had recently returned from Ecuador. The situation was so desperate that García de Solís traveled personally to Guatemala with ten soldiers. He left Buena Esperanza in October 1535 and arrived in Santiago de Guatemala in late November.

Abandonment of Buena Esperanza, 1536

By December, there was still no news from García de Solís. No Spanish help had arrived from anywhere else. The Spanish at Buena Esperanza had lost hope. They were pressured from all sides by hostile natives, led by Sicumba. Andrés de Cerezeda heard about Sicumba's plan to attack and destroy Buena Esperanza. In response, he sent parties to capture and execute hostile native leaders. This stopped the immediate threat, though Sicumba managed to escape.

Soon after, a Spaniard named Gonzalo Guerrero arrived from Yucatán. He had 50 canoes of Maya warriors. Guerrero had been captured by the Maya in Yucatán and had "gone native," fighting with them. He now came to help the native resistance in Higueras. But he arrived too late for the planned attack on Buena Esperanza.

By May 5, 1536, the town council of Buena Esperanza had lost all faith in Cerezeda. They voted to abandon Higueras and return to Trujillo. Cerezeda opposed this, but the council forced him to agree. Meanwhile, any group leaving Buena Esperanza to find food had to have at least 20 members for defense. A chaotic evacuation back to Trujillo began. Resentment against Cerezeda was so strong that he feared for his life. He fled to Naco to find safety among friendly natives. On May 9, during this disordered Spanish retreat, García de Solís returned from Guatemala. He brought news that help would soon arrive.

Pedro de Alvarado Arrives, 1536

Because of this political instability, the colonists asked Pedro de Alvarado for help. This led to talks between Alvarado and Francisco de Montejo. Montejo tried to give up his claim to govern Honduras-Higueras to Alvarado. Alvarado considered giving his governorship of Chiapas to Montejo in exchange. They asked the Crown for permission. But the Crown refused the exchange. It required Montejo to take up his governorship of Honduras-Higueras. News of this refusal arrived after Alvarado had already launched his relief expedition, due to slow communication with Spain.

Alvarado was interested in reports of gold. He also wanted to prevent the Spanish from completely abandoning the territory. He invaded Higueras in 1536. He had 80 well-armed Spanish soldiers, both foot soldiers and cavalry. He was also joined by about 3,000 native Guatemalan allies. Many of these allies were Achi Maya warriors, known for being fierce. He also brought native and African slaves to work in the mines. And he brought livestock to help with colonization.

His route took him past a strong native fort called the Peñol de Cerquín. Native warriors had gathered there to fight the Spanish. Alvarado saw how strong the fort was. He also knew he needed to help Buena Esperanza quickly. So, he decided not to attack the fort and pushed on to help his countrymen.

Strengthening Higueras

Pedro de Alvarado arrived at Buena Esperanza just as it was being abandoned. His sudden appearance stopped the exodus. Many colonists who had already left returned. Andrés de Cerezeda sent messages from Naco, begging Alvarado to take over as governor. The town council met and appointed Alvarado as justicia mayor (chief judge). They also made him captain-general of Honduras-Higueras until the Crown appointed someone else or confirmed him.

Alvarado's presence instantly boosted Spanish morale. The groups that had caused problems in the colonial government disappeared. The colonists united behind the new governor. Alvarado, known to the natives by his Nahuatl nickname Tonatiuh, had a fearsome reputation among the native people. They had heard of his ruthless actions elsewhere. Alvarado quickly reestablished strong Spanish control over the area around Buena Esperanza. He founded a military camp in Tencoa. He successfully set up profitable gold and silver mines in Higueras.

Once this was done, Pedro de Alvarado sent Juan de Chávez, one of his trusted officers. Chávez led 40–50 Spanish soldiers and about 1,500–2,000 native allies. Their mission was to explore the mountainous interior of the province. They were to find a good, defensible location for a new colonial capital. Ideally, this would provide a communication route between Higueras and Guatemala.

Defeat of Sicumba

The natives of the Sula Valley, led by their cacique Sicumba, fought fiercely against Alvarado's forces. Alvarado marched to the lower parts of the Ulúa Valley to finally end Sicumba's resistance. Sicumba was confident in his strong fort on the banks of the Ulúa River. He also trusted his warriors, who were reinforced by Maya warriors brought by Gonzalo Guerrero. These Maya allies were likely from Chetumal, in Yucatán, where Guerrero had settled.

Alvarado launched a two-pronged attack by land and water against the fort. He was supported by native Guatemalan allies and artillery. Fighting happened around the fort's walls and on canoes in the river. Attempts to storm the landside wall failed. Alvarado's attack succeeded by using artillery mounted on canoes, firing from the river.

Alvarado won a decisive victory over the native leader. Sicumba and many of his nobles and warriors were captured. Native resistance was broken. Gonzalo Guerrero was found among the dead. He was wearing Maya-style clothing and warpaint. Sicumba's army scattered. Alvarado then attacked a series of native forts, which fell quickly. In a short time, Alvarado established Spanish control over the entire coastal plain. After the battle, Alvarado divided the territory and its people into encomienda grants. He took Ticamaya for himself. Sicumba and his people converted to Christianity and became Spanish subjects. Sicumba settled in Santiago Çocumba in the south of the Ulúa Valley (modern Santiago, in Cortés Department). Sicumba's resistance ended after ten years of successful fighting against Spanish attacks. Alvarado brutally suppressed native resistance. His merciless treatment of the native population only made them hate the invaders more.

Founding of San Pedro Sula, June 1536

After defeating Sicumba, Alvarado led his army to the native village of Choloma. This was in the area of Puerto de Caballos. On June 27, 1536, Alvarado founded a Spanish town next to the native settlement. He named it Villa de Señor San Pedro de Puerto Caballos (modern San Pedro Sula). The new town had 35 Spanish citizens. Alvarado assigned 200 of his slaves to help build the town and work the surrounding fields. He sent expeditions into nearby regions to secure the new town, expand Spanish control, and gather supplies. Alvarado canceled all encomienda rights that Cerezeda had established in the area. He reassigned the villages to the citizens of San Pedro.

Juan de Chávez at the Peñol de Cerquín

While Alvarado was strengthening his power in the Ulúa Valley, Juan de Chávez's expedition in southern Higueras met strong resistance. They had marched up the Naco valley to the Peñol de Cerquín ("Rock of Cerquín"). Alvarado had bypassed this fort on his first trip. The Peñol de Cerquín was a very strong rocky butte that the natives had fortified. Many natives had gathered at the fort. It controlled all of southern Honduras. The natives were dug in and determined to stop any Spanish attempt to pass. It is not known who led the native resistance at this time. But it may have been Lempira, a war leader who would later become famous for fighting the Spanish.

Juan de Chávez tried to storm the Peñol de Cerquín. But he could not even reach its base. So, he decided to lay siege to the fort. But he was short on supplies. The local natives were all gathered to fight, so there was no one left to provide food for the Spanish. Spanish morale was low. It was clear how hard it would be to storm the fort. Most Spanish soldiers had homes and encomiendas in Guatemala and wanted to return there. After some time, Chávez was forced to retreat because his troops were close to rebelling. He planned to find an easier victory to boost morale. He also wanted to resupply before returning to attack the fort. He also thought his retreat would allow the hostile natives to farm their fields around the Peñol de Cerquín. This would provide food when he returned later to renew the attack.

Preparations to Found Gracias a Dios, July 1536

Juan de Chávez headed for the Valley of Maniani. Cerezeda had suggested this as a good place for a new town. It is likely the Spanish chose the native town of Maniani for the new Spanish settlement. On July 20, 1536, Pedro de Alvarado sent orders to found the new city. It was to be called Gracias a Dios. This was to improve communication between Honduras and Guatemala.

Alvarado used the town of Tencoa as a base. He sent his brother Gonzalo with 40 Spanish soldiers and an unknown number of native allies. They were to help establish the new town. Alvarado appointed the members of the town council. He assigned 100 Spanish citizens to live there. However, the natives around Gracias a Dios were not fully conquered. There were violent native rebellions in the province until around 1539. As in San Pedro, Alvarado canceled all previous encomiendas in the region and reassigned them.

Gonzalo de Alvarado had been exploring the central region. This included Siguatepeque, the Tinto River, and Yoro. He successfully dealt with native resistance and collected supplies for San Pedro. He had about a dozen cavalry and 15 foot soldiers. He joined with ten more soldiers under Gaspar Suárez de Ávila, who was his lieutenant. They went to Gracias a Dios with the legal documents to formally establish the town.

Departure for Spain, August 1536

In 1536, the natives of Yamala, near Tencoa, rebelled. The Spanish responded by burning the natives' homes and storehouses. Around mid-1536, Pedro de Alvarado received news. Alonso de Maldonado had been appointed to investigate his governorship of Guatemala. And Francisco de Montejo had finally accepted the governorship of Honduras and was on his way. Alvarado was angry. His strong actions had prevented the complete collapse of Spanish colonization efforts. He now believed the Spanish position was secure. With Spanish control seemingly firm in Honduras, he traveled to Puerto de Caballos and sailed back to Spain. He left the province in mid-August to deal with his legal problems.

Founding of Gracias a Dios

Meanwhile, Gonzalo de Alvarado and his soldiers pushed south to meet Juan de Chávez. They were already tired from their previous trips. Both men and horses were in bad shape. Supplies were a constant worry. Their progress was further slowed by the start of the rainy season. And by constant resistance from hostile natives. After three or four months, Gonzalo de Alvarado arrived at Lepaera. They expected to find Chávez and his men there.

Unable to find them, Alvarado sent his lieutenant Suárez de Ávila to scout the area. He eventually returned with news that Chávez, facing a mutiny from his men, had marched back to Guatemala. Since Pedro de Alvarado had already left for Spain, this made Gonzalo the highest-ranking Spanish officer in Honduras-Higueras.

Gonzalo de Alvarado and his men decided to stay. The area seemed populated enough to provide valuable tribute. And earlier explorations had already found precious metal deposits there. Alvarado decided to found the new town of Gracias a Dios at Opoa. This was instead of the nearby site Chávez had chosen. In late 1536, Gonzalo de Alvarado finally founded the new town. He assigned officials as his brother had instructed. Although Pedro de Alvarado had assigned 100 citizens, in reality, it had about 40 upon its founding. The town only stayed at Opoa for a short time before being moved to a new site.

Gonzalo and his men campaigned to take control of a wide area. They went as far as the Comayagua valley. Although they claimed to conquer a wide region, Gonzalo had too few soldiers to control it effectively. Native resistance was so strong that the colonists soon faced starvation. The natives refused to serve the Spanish. San Pedro was in a similar situation. It could not provide any help to Gracias a Dios. The colonists asked Alonso de Maldonado in Guatemala for help. They were told that Francisco de Montejo would soon become governor and would provide any necessary assistance.

Temporary Decline, 1536–1537

Pedro de Alvarado's conquest of Honduras was not very deep. It was mostly limited to Higueras. His conquest of the Naco valley and the lower Ulúa River established a Spanish presence there. But beyond that, Spanish control was weak. Expeditions had gone deep into Honduras. And distant native rulers had come to show respect to the Spanish Crown.

The settlement at Gracias a Dios was not as secure as it seemed when Alvarado left. And no effective help had been sent to Trujillo. Many native rulers, who had been scared by Alvarado's reputation and military skill, rebelled as soon as he left the province. Alvarado had also encouraged the enslavement of natives who fought against the Spanish. He also allowed their sale and generally harsh treatment of the native population. This caused a lot of anger among the natives. It made them likely to rebel. Many natives resisted passively. They did not provide supplies or labor to their encomendero overlords. Continued slave raids and brutal treatment by the Achi Maya allies increased their hatred and resistance. Many natives abandoned their settlements and fled to the mountains and forests. Most of the areas around San Pedro and Gracias a Dios were at war. The Spanish position was again in danger.

Francisco de Montejo's Arrival

Francisco de Montejo borrowed a lot of money to pay for his trip to Honduras. He used his large land holdings in Mexico as a guarantee for the loans. He also sold some of his property. He announced his expedition in Mexico City and Santiago de Guatemala. He attracted many new recruits. He often paid for their equipment himself. He also bought ships at Veracruz. In 1537, Francisco de Montejo became governor. He canceled the encomiendas that Pedro de Alvarado had given out. This made Alvarado's supporters resist Montejo and his chosen officials. Montejo assigned Alonso de Cáceres as his captain in Honduras.

Alonso de Cáceres, 1536–1537

While Francisco de Montejo was preparing his large expedition, he heard about the dangerous situation of the Spanish in Higueras. Fearing the colony would collapse, he appointed Alonso de Cáceres as captain-general. He sent Cáceres ahead with a small group of soldiers. They were to travel overland through Santiago de Guatemala, recruiting more soldiers along the way. Cáceres was an experienced officer. He had already fought in the conquest of Yucatán. In Santiago, Cáceres recruited 20 more cavalry. He also got more weapons and supplies. He arrived in Gracias a Dios with his relief force in late November or early December 1536. He described the settlement as being in a terrible state. His expedition provided temporary relief. Morale improved with the news that Montejo would soon be in Honduras. However, there was some political resistance to Cáceres from the town council. This council, appointed by the Alvarados, wanted Pedro de Alvarado to remain governor. They wanted Honduras to be united with Guatemala. This led to plotting among factions.

Since Alvarado's supporters were confirmed in the town council of Gracias a Dios, they used complex legal arguments to refuse Cáceres's authority. He withdrew to a nearby native village and planned to overthrow the town council. The Spanish infighting encouraged the local natives to defy the invaders. Cáceres launched a surprise attack at dawn in early 1537. He entered Gracias a Dios with 20 well-armed soldiers and imprisoned the town council, including Gonzalo de Alvarado. Cáceres declared Montejo as governor of Honduras-Higueras. He named himself as lieutenant governor and captain-general. He met little opposition from most of the Spanish citizens. He then appointed a new town council.

Cáceres left Gracias a Dios under the command of Suárez de Ávila. He launched attacks against the strong native resistance. He went into the mountainous region of Cares, around the Peñol de Cerquín. He had some success against fierce native resistance. He went eastward to the Comayagua valley and brought a large region under Spanish control.

Montejo Arrives in Higueras, March 1537

Francisco de Montejo traveled overland from Mexico with his large expedition. It included soldiers, Mexican allies, supplies, and livestock. He sent a smaller group by sea with more supplies, his family, and household. He arrived in Santiago de Guatemala in early 1537. There, he bought more supplies, weapons, and livestock. These new supplies included cattle, sheep, pigs, crossbows, arquebuses, and gunpowder. He now had between 80 and 100 Spanish soldiers, including veterans from Yucatán. He arrived in Gracias a Dios in late March 1537, while Cáceres was still in the Comayagua valley.

The sea-borne group did not fare as well. After resupplying in Cuba, pirates plundered it. There was little loss of life, but most supplies were taken. With what could be saved, they put into Puerto de Caballos in the spring of 1537. Montejo met them there. The strong combined Spanish force now in Honduras-Higueras put Montejo in a strong position, both militarily and politically. Montejo was installed as governor without opposition on March 24 at Gracias a Dios. He released the imprisoned members of the former town council. He sought their support for continued conquest.

Montejo immediately tried to stop the worst abuses by the Spanish. He stressed to the colonists the need to treat the natives fairly and legally. He sent many of the Achi Maya allies back to Guatemala. This was because they had caused harm among the generally peaceful Chontal Maya of the Sula coast. Montejo's moderate actions encouraged many natives to return to their villages, especially around Gracias a Dios. The encomienda system began to work as intended. This greatly eased the constant struggle for supplies.

Conquest of the North

Montejo then set out to pacify the north coast. He left Suárez de Ávila in command of Gracias a Dios. He first went to San Pedro to present his official governorship documents. He was recognized as governor on April 16. The next day, he canceled all encomiendas issued by Pedro de Alvarado in both San Pedro and Gracias a Dios districts. He then re-divided the province among his own soldiers and supporters.

Montejo then sent Alonso de Reinoso with about a hundred soldiers into the mountains around San Pedro. Their task was to put down native resistance. Montejo marched to Naco. Previous campaigns by Cerezeda and Alvarado had left a large native population scattered from their settlements and hostile to the Spanish. Victory was quick. Many native rulers came to swear loyalty to Montejo. They begged him to protect the trade route to Yucatán. They offered their loyalty in return. Montejo accepted their requests. He considered a large stretch of the north coast to be finally conquered and under effective Spanish control. He applied the same moderate treatment to the natives that had worked so well around Gracias a Dios. This had similar results. Many returned to their villages, and the encomienda system began to function.

Founding of Santa María de Comayagua

In spring 1537, Francisco de Montejo sent more soldiers to Alonso de Cáceres. Cáceres was still in the fertile Valley of Comayagua. By late spring or early summer, the valley had been completely conquered. In December 1537, under orders from Montejo, Alonso de Cáceres founded the town of Santa María de Comayagua. It was placed in a strategic spot, halfway between the Caribbean and Pacific coasts. Cáceres then distributed the native settlements using the encomienda system. He gathered more soldiers from Gracias a Dios. Then he immediately returned to Comayagua. He began to push eastward towards Olancho.

By summer 1537, Montejo believed that Higueras had been almost completely pacified. There were very few deaths among either the Spanish or the natives. Gracias a Dios and San Pedro were more secure. Many natives had returned to their villages, encouraged by Montejo's fair policies. In reality, only the areas around the Spanish settlements had been fully conquered. In the more remote areas, most natives were still hostile to the Spanish and determined to resist. Unlike in other provinces, the Spanish could not find reliable native allies to help their conquest.

The Great Revolt, 1537–1539

As a sign of future problems, three Spaniards passing near the Peñol de Cerquín were attacked and killed. This area was thought to be peaceful. The attack deeply worried Montejo. Similar incidents during his conquest of Yucatán had led to widespread uprisings. He rushed to the scene with a strong force. He called all the native leaders to meet him. He wanted to prevent a rebellion. He investigated the attack and punished those most responsible. Then he continued with friendly policies towards the other leaders, who reaffirmed their loyalty. Montejo let the leaders return to their people. Then he marched to Comayagua to reinforce Cáceres. After that, he returned to Gracias a Dios.

Lempira's Alliance

After Pedro de Alvarado's brutal actions in western Honduras, native resistance against the Spanish grew stronger. It gathered around the Lenca war leader Lempira. He was said to have led an army of 30,000 native warriors. Lempira had been secretly building a powerful alliance in southern Higueras. This was in the mountains south of Gracias a Dios. Its political center was the town of the Lenca ruler Entepica. Its strongest fort was Lempira's hilltop fortress at Peñol de Cerquín.

Lempira also gained support from natives in the Comayagua valley and the San Pedro mountains. Even Lempira's former enemies, like the Cares, swore loyalty to him after he defeated them in battle. Through a mix of force and diplomacy, Lempira's alliance reached as far as San Miguel, in eastern El Salvador. It included about 200 towns. Resistance continued from 1537 into 1538. Then Lempira and his forces were defeated in battle by the Spanish, led by Alonso de Cáceres.

Spanish expeditions had often crossed Lempira's territory, especially the Cares region. They believed it was peaceful. In secret, Lempira planned an uprising near his fort at Peñol de Cerquín. If it succeeded, he planned a widespread revolt across all his territory. Lempira strengthened the defenses of the Peñol de Cerquín. He gathered many warriors, supplies, and weapons there. Experienced Spanish soldiers, veterans of European wars, were impressed by the strength of the defenses. They compared them favorably to those they had seen in Europe.

Towards the end of 1537, Lempira was ready. Natives left their villages and gathered at the Peñol de Cerquín. His warriors prepared for battle. Lempira sent messages to the native allies of the Spanish. He urged them to leave their foreign rulers and join his forces. But they refused. Only when war was declared did the Spanish realize the threat from Lempira and his alliance. Although the immediate danger was limited to the area near the Peñol de Cerquín, the Spanish understood that a rebellion at such a strong fort was a powerful symbol of native independence throughout Higueras. Francisco de Montejo immediately sent Alonso de Cáceres against Lempira. Cáceres had 80 well-armed Spanish soldiers, along with Mexican and Guatemalan native allies. Montejo sent messengers asking for help from Santiago de Guatemala and San Salvador.

Siege at the Peñol de Cerquín