Chetumal Province facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Province of Chetumal

u kuchkabal Chetumal (Yucatecan Mayan)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ca. 950–1544 | |||||||||||

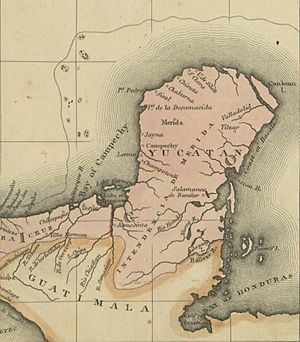

Map of Yucatan showing Salamanca de Bacalar

|

|||||||||||

| Status | Dissolved | ||||||||||

| Capital | Chichen Itza; Mayapan; Chetumal | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Yucatecan Mayan | ||||||||||

| Religion | Mayan polytheism; Cult of Kukulkan | ||||||||||

| Government | Theocratic, absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

|

• ca. 1441-1446

|

Ah Xiu Xupan (last) | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

|

• ca. 1514–1544

|

Nachan Kan (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Postclassic to Spanish conquest | ||||||||||

| ca. 950 | |||||||||||

| ca. 1250 | |||||||||||

| 1527–1544 | |||||||||||

| 4 March 1544 | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | Belize; Mexico | ||||||||||

Chetumal, also known as the Province of Chetumal, was an important Mayan state in the Yucatan Peninsula. It existed during the Postclassic period of Mayan history. This was a time after the Classic Maya civilization declined.

Contents

History

Early Settlements

The first people settled in the Chetumal area before 8000 BC. These were early people during the Stone Age. Around 2000 BC, Mayan farmers from the Guatemalan highlands created the first lasting settlements. By 100 AD, the first state or province in Chetumal was likely formed. This happened during the Late Preclassic period.

After the Classic Maya Decline

The end of the Classic Mayan period in Yucatan led to new Mayan provinces. Powerful cities like Chichen Itza expanded their control. The decline was not too bad in the Chetumal area. At least 25 settlements survived. They likely focused on trade along the coast, which Chichen Itza controlled.

Chichen Itza was a very strong city-state from about 750–800 AD to 1050–1100 AD. It began conquering other areas around 900 AD. This led to the creation of various provinces, possibly including Chetumal.

Later, Mayapan became the most powerful city-state in Yucatan. This happened around 1080–1104 AD or 1185–1204 AD. Mayapan's rule lasted for about 13 k'atuno'ob (periods of 20 years). It ended around 1392–1416 AD or 1441–1461 AD.

Around 1450 to 1500 AD, a ruler named Pachimalahix I from another area attacked Chetumal's capital. He demanded tribute. Some think he might have raided the city to settle trade problems instead.

Contact with Europeans

First Meetings with Spaniards

The first known Spaniard to reach Chetumal was Gonzalo Guerrero. He was a sailor from Spain. In 1514, Guerrero started working for Chetumal's government or military. He was probably given to Governor Nachan Kan as a slave. By 1519, Guerrero had fully adopted Mayan culture. He married Governor Kan's daughter and had three children with her. Guerrero then helped plan military strategies for Chetumal and other Mayan states against Spanish attacks.

Before Guerrero's arrival, people in Chetumal might have heard about Spaniards. This could have happened through trade networks. Mayan settlements near Cozumel, Lake Izabal, and Guanaja traded with Chetumal. Any news about non-native people would have spread.

Spanish Expeditions from Cuba

Fights between the Spanish and Mayans began on March 5, 1517. This happened at Cape Catoche. A Spanish group led by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba was attacked. Other Mayan groups also resisted the Spanish. This stopped the Spanish from achieving their goals of finding riches.

However, the Spanish reports of grand Mayan cities encouraged more expeditions from Cuba. These included a trading trip by Juan de Grijalva in 1518. Another trip in 1519 was led by Hernán Cortés. Cortés's trip quickly turned into the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. A smallpox epidemic also spread from 1519–1521. This disease likely affected Chetumal very badly.

Montejo's Expedition (1527–1528)

On December 8, 1526, a Spanish leader named Francisco de Montejo was given permission to conquer Yucatan. He had been part of earlier expeditions. Montejo quickly began his conquest.

Montejo chose his friend, Alonso Dávila, to lead the main part of his expedition. They sailed from Spain in June 1527 with 4 ships and over 250 men. They landed in Cozumel in September 1527.

They stayed in Cozumel for a few days. The people there welcomed them. Then they went to the mainland. They explored the area and were welcomed by towns like Xelha and Zama. In October 1527, they founded a settlement called Salamanca. But the Spanish demanded too much food. Soon, their supplies ran low. In late 1527 or early 1528, after facing hunger and disease, the Spanish moved north. They were well received in the Ekab Province. They fought and won battles in Chikinchel and Ake. After this, they returned to Salamanca in mid-1528. They got more supplies and planned a new attack southwards.

Montejo sailed along the coast with a small group. Dávila took a parallel route by land with most of the soldiers. The capital of Chetumal was their meeting point. Montejo arrived first. He learned that Gonzalo Guerrero was the commander of Chetumal's forces. Montejo sent a message asking Guerrero to join the Spanish. Guerrero refused. Chetumal prepared for battle. Guerrero's plan was to keep Dávila and Montejo separated. Guides were sent to lead Dávila away from the capital. The capital then tricked Montejo into believing Dávila's group was lost. Montejo sailed south, then back north. He soon realized the trick. He decided to get more soldiers in Veracruz for a new attack on Chetumal.

Dávila's Expedition (1531–1533)

In early 1531, Montejo planned another campaign towards Chetumal. Alonso Dávila was chosen to lead about fifty men.

Dávila left the capital of Can Pech in mid-1531. They marched through other provinces without problems. They reached Chable, a town in the Waymil Province. The people there offered help. Dávila marched on to Bacalar without resistance. He found that he could not reach Chetumal by land. So, they used large canoes. They landed in Chetumal without a fight because the capital was empty. Dávila decided to build a town there. He called it Villa Real.

Over the next two months, Chetumal's Governor, Nachan Kan, gathered his forces. Dávila attacked them by surprise. Many of the Mayan men were killed, and over sixty were captured. But Governor Kan escaped.

Dávila then explored the area around Villa Real. He found that people in other towns were now against him. Their towns were blocked. The Spanish quickly defeated this resistance. However, another province, Cochuah, had rebelled. Dávila went to stop this revolt. The Cochuah revolt was serious. Dávila had to retreat to Villa Real. The Spanish settlement was now under a heavy attack. With only about thirty men able to fight and few supplies, their situation was difficult.

Dávila learned about a large group of traders preparing to sail near Villa Real. He seized their goods and captured them. One prisoner was the son of a mayor from a town called Tapaen. Dávila kept the son hostage to try and get the mayor to cooperate. When the mayor didn't help, Dávila used harsh tactics to pressure him.

The siege lasted for months. It became clear that the Spanish could not hold Villa Real. In autumn 1532, Dávila and his council decided to leave by sea. They reached Trujillo in spring 1533 after a difficult seven-month journey.

Pacheco's Expedition (1543–1544)

In April 1543, Montejo sent Gaspar Pacheco to conquer Chetumal and Waymil. Pacheco gathered about 25 to 30 men. He made Melchor Pacheco his second-in-command. The expedition started in late 1543 or early 1544.

Pacheco's group first reached the Spanish-controlled Cochuah Province. The people there were suffering from war. The Spanish took men and women as servants. They also seized so much food that it caused a famine. Gaspar Pacheco fell ill. He then put Melchor Pacheco in charge of conquering Waymil and Chetumal.

As the Pachecos marched, they found that people had burned their crops and fled into the woods. The Mayans planned to fight using guerrilla warfare. The Spanish used very harsh methods to try and stop the resistance.

By early 1544, the local resistance was very weak. The Pachecos decided to build a town. They called it Salamanca and built it in the ruins of Bacalar. This victory came at a high cost. Many people in Waymil and Chetumal died or left. This made Salamanca a very poor town.

Society

Religion

Chichen Itza promoted the worship of K'uk'ulkan. This religion is thought to be the first state religion that united different Mayan groups. It also helped strengthen trade along the coast.

Some believe that Chetumal had a special cult for the god Itzamna. This cult focused on his connection to large ocean creatures. Art found in Chetumal often shows Itzamna coming out of the mouths of sea animals.

Government

Before the Spanish Arrived

Chichen Itza was likely ruled by a council of lords. Or it might have been ruled by a king with a special council. Its lands were probably managed as a group of provinces.

Mayapan was generally ruled by a council of lords. These lords came from important noble families. Mayapan's lands were organized as a group of provinces. This was called the League of Mayapan. Each province had a kalwak or governor.

During the Spanish Contact Period

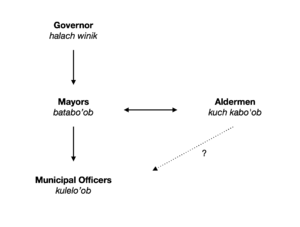

Chetumal's government as a free province probably stayed the same. It was likely similar to other nearby provinces. These provinces had a halach winik or governor.

State Leaders

Chetumal's main leader was the halach winik or governor. He was also the batab or mayor of the capital city. This position and title (Ahaw or Lord) were passed down through families. His rule was seen as a given by the gods. The governor's jobs included:

- Collecting payments from cities, towns, or villages.

- Calling men to join the army during war.

- Leading wars.

- Being the highest judge for problems between towns.

- Leading state religious ceremonies.

One of Chetumal's later governors also had power over part of a neighboring province. This was probably done through threats, not diplomacy.

Local Leaders

Below the governor were the batabo'ob or mayors. These mayors led the cities, towns, and villages. This position was also passed down through families. The mayor's jobs included:

- Having a town farm for his own benefit.

- Keeping houses and farms in order.

- Being a judge for local civil and criminal cases.

- Keeping the military or local fighters ready during peacetime.

The exact setup of local government is not fully known. But these positions were part of some cities, towns, or villages:

- nakomo'ob or commanders-in-chief: They led the local military in war, instead of the mayor.

- kuch kabo'ob or aldermen: They managed parts of the town. Together, they could stop some of the mayor's decisions.

- kulelo'ob or town officers: They carried out the mayor's orders.

Local governments also managed the commons. This included all town land. Private land ownership might not have existed. It is not clear if non-town land was also shared.

Economy

The Capital City

Since about 1450, Chetumal's capital was a major port. It was part of the coastal trade route. This route went from the Ulua River to the Ekab Province. Around the time the Spanish arrived, it was a large town with about 2,000 houses. It was surrounded by fruit orchards, corn fields, and bee farms. Its merchants had a large presence in Nito, a port outside the province. Chetumal traded its cacao (for chocolate), honey, wax, and sea products. In return, it got obsidian, jade, turquoise, copper, and gold.

The Province's Economy

Chetumal was the only major cacao producer in Yucatan. It supplied the capital's merchants with cacao, honey, wax, and sea products. Goods for local use probably included:

- Pottery from Lamanai and places on Honey Camp Lagoon.

- Salt and salted fish from places on the Northern River Lagoon.

Legacy

Historical Research

None of Chetumal's own records still exist. So, all we know about the province comes from later Spanish-Mayan records and modern archaeology.

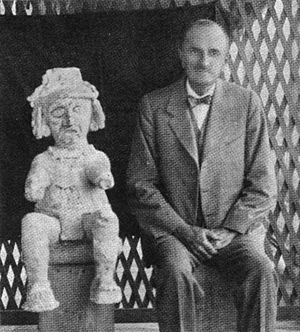

Archaeological work in Chetumal began in 1894. Thomas Gann, a doctor from colonial Belize, started it at the ruins of Santa Rita, Corozal. His work led to more explorations in Belize and Mexico. He worked with Sir J. E. S. Thompson on a major book about Mayan history. Gann's collections of Mayan artifacts are in several museums. His work might have led to the first laws protecting ancient sites in Belize in 1894.

After Dr. Gann, archaeological work in Chetumal slowed down. It picked up again with the Altun Ha Expedition from 1964–1970. This project led to a lot of new discoveries. It started a new era of archaeological work in Chetumal that continues today.

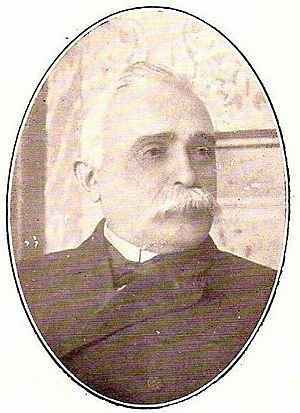

Books about the Postclassic Mayan states were first published in 1896 by Juan Francisco Molina Solís. Later, Ralph L. Roys published important works in 1943 and 1957. His 1957 book is considered the most important on the topic. Even with this progress, Chetumal was still not well understood. This changed with a key book by Grant D. Jones in 1989.

Cultural Impact

In Mexico

The modern city of Chetumal was founded on May 5, 1898. It was named after the ancient capital of the Chetumal Province.

The Guerrero–Kan family is widely believed to be the first Mestizo (mixed heritage) family in the Americas. Many artworks showing them have been placed in Yucatan and Quintana Roo. These include:

- A sculpture by Raúl Ayala Arellano in Akumal (1975).

- Many copies of this sculpture, including one in Merida (1980).

- A mural called Nacimiento de la raza mestiza (Birth of the Mestizo Race) by Nereo de la Peña in Chetumal (1979).

- A mural called Forma, color e historia de Quintana Roo (Form, Colour and History of Quintana Roo) by Elio Carmichael Jiménez in Chetumal (1981).

- A sculpture called Alegoría del mestizaje (Allegory of Mixed Heritage) by Carlos Terrés in Chetumal (1981).

- A sculpture called Cuna del mestizaje (Cradle of Mixed Heritage) by Rosa María Ponzanelly and Sergio Trejo in Chetumal (1996).

- A mural called La cuna del mestizaje by Rodrigo Siller in the Museum of Mayan Culture, Chetumal (2007).

- An oil painting of Gonzalo Guerrero by Fernando Castro Pacheco in Merida.

In 1978, the people of Cancun gave a turtle-shell statue of Gonzalo Guerrero to the King and Queen of Spain. Quintana Roo's state anthem, created in 1986, celebrates the Guerrero–Kan family. The highest award in Othon P. Blanco was named after Guerrero in 1997.

In Belize

On December 20, 2012, the National Institute of Culture and History and the Belize Tourism Industry Association held a public re-enactment of the Guerrero-Kan wedding. This took place at Santa Rita, Corozal. Similar re-enactments have been held several times since then.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Chactemal para niños

In Spanish: Chactemal para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |