United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution facts for kids

Quick facts for kids United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mexican Revolution | |||||

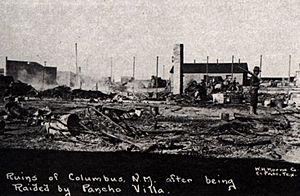

Aftermath of Pancho Villa's attack on Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916 |

|||||

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

| Maderistas

Huertistas Villistas Constitutionalistas Carrancistas |

|||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Francisco Madero Victoriano Huerta Pancho Villa Venustiano Carranza Alvaro Obregon |

|||||

The United States' involvement in the Mexican Revolution was complex and changed over time. From 1910 to 1920, the U.S. government sometimes supported and sometimes went against different Mexican leaders. This was mainly for economic and political reasons. The U.S. usually supported those in power but could refuse to officially recognize them.

Before Woodrow Wilson became president in 1913, the U.S. mostly warned Mexico. They said they would act if American lives or property were in danger. President William Howard Taft sent troops to the U.S.-Mexico border. However, he did not let them directly join the fighting. During the Revolution, the U.S. sent troops into Mexico twice. They occupied Veracruz in 1914. They also went into northern Mexico in 1916 to try and capture Pancho Villa. This mission was not successful.

Contents

- Why the U.S. Got Involved in Mexico

- U.S. Relations with President Madero (1911–1913)

- U.S. and the Huerta Government (1913–1914)

- U.S. and the Warring Revolutionary Groups (1914-1915)

- Events of 1916–1917

- Border Clashes (1918–1919)

- Foreigners Fighting in Mexico

- U.S. Military Awards

- Images for kids

- See also

Why the U.S. Got Involved in Mexico

The U.S. saw Latin America as its special area of influence. This idea was part of the Monroe Doctrine. However, the U.S. did not get involved in the Mexican Revolution all the time. Its role was often less direct than people might think.

U.S. Business Interests in Mexico

During the long rule of President Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911), Mexico tried to modernize. Díaz invited foreign businesses to invest in the country. Laws were passed that helped these investors. This led to more economic inequality in Mexico.

American businesses invested a lot of money, especially near the U.S.-Mexico border. This happened during the many years Díaz was in charge. The two governments worked closely together on economic matters. This cooperation depended on Díaz helping U.S. investors.

The U.S. and Díaz's Downfall

In 1908, Díaz said he would not run for re-election in 1910. This led to many people wanting to become president. But Díaz changed his mind and ran again. He then put the main opposition candidate, Francisco I. Madero, in jail.

Madero escaped to San Antonio, Texas. He called for the 1910 elections to be cancelled. He declared himself the temporary president. Madero asked the Mexican people for their support. His plan, called the Plan of San Luis Potosí, started revolutionary uprisings. These happened mostly in northern Mexico.

The U.S. stayed out of these events at first. But on March 6, 1911, President William Howard Taft sent troops to the U.S.-Mexico border. This was seen by Mexicans as the U.S. taking a side against Díaz.

U.S. Relations with President Madero (1911–1913)

After Díaz resigned in 1911, Francisco I. Madero was elected president in October 1911. U.S. President Taft was nearing the end of his term. He had lost the 1912 election and would leave office in March 1913.

During this time, Taft's Ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson, worked to remove Madero from power. Ambassador Wilson was against Madero from the start. He wanted the U.S. to intervene in Mexico. Wilson controlled the information he sent to the U.S. government. This meant Washington did not fully understand the situation.

Wilson also caused trouble by giving false information to local newspapers. When Madero tried to control the newspapers, they claimed he was unfair. Madero had won a fair election after the revolution made Díaz's rule impossible. A treaty was signed in May 1911. It said Díaz would resign, a temporary government would be set up, and new elections would be held. Madero made a mistake by disbanding his rebel forces. He kept the old Federal Army, which had just been defeated.

Early Rebellions Against Madero

Just a month after Madero took office, General Bernardo Reyes rebelled. Reyes had been a close advisor to Díaz. He came from Texas and called for people to rise against Madero. His rebellion failed completely. Madero had been elected with huge support. For a short time, the U.S. was hopeful about Madero's government. Reyes was arrested and imprisoned.

Madero did not keep all his promises, especially about land reform. This led to a peasant rebellion in Morelos led by Emiliano Zapata. The U.S. did not care much about this rebellion. There were no U.S. investments in that area. But Madero's struggle to stop the rebellion made people doubt his leadership.

Another serious uprising against Madero was led by Pascual Orozco. Orozco had helped the rebels win in the north. He was unhappy that he was not given a bigger role. He also felt Madero was not moving fast enough on land reform. Orozco's rebellion was a bigger challenge for Madero. Some U.S. businesses helped fund this rebellion.

General Félix Díaz, Porfirio Díaz's nephew, also started a rebellion in October 1912. He had some support from the U.S. government. Díaz wanted to bring back order and progress. The U.S. sent ships to the Gulf Coast during Díaz's rebellion. Despite U.S. support, Díaz's rebellion failed. He was arrested and imprisoned. However, the U.S. still saw him as the best choice to replace Madero.

The Ten Tragic Days and Madero's Fall

The U.S. government and businesses felt Madero could not bring order to Mexico. Ambassador Wilson made it clear he wanted Madero replaced. He wanted a leader who would be more friendly to the U.S.

A coup against Madero seemed likely by January 1913. It was supported by the U.S. The plot by Díaz and Reyes against Madero began in February 1913. This period is known as the Ten Tragic Days. Madero was overthrown. Ambassador Wilson brought Félix Díaz and General Victoriano Huerta together. Huerta was supposed to defend the president but turned against him.

On February 19, they signed an agreement called the Pact of the Embassy. This plan for sharing power had the clear support of the U.S. ambassador. U.S. President William Howard Taft was a "lame duck" president. He had lost the election to Woodrow Wilson, who would become president on March 4, 1913.

In his final days, President Madero realized he was losing power. He asked President-elect Wilson for help. But Wilson was not yet in office. Ambassador Wilson had gained the support of other foreign diplomats in Mexico. He pushed for the U.S. to recognize General Huerta as the new leader.

U.S. and the Huerta Government (1913–1914)

Woodrow Wilson became president in March 1913. By then, the coup in Mexico was complete. The elected president Madero had been murdered. President Wilson refused to recognize Huerta as Mexico's leader. From March to October 1913, Wilson pressured Huerta to resign. He also urged European countries not to recognize Huerta's government.

Huerta announced elections, planning to run himself. In August 1913, Wilson stopped arms sales to Huerta's government. This reversed the easy access Huerta had to weapons before. Huerta later withdrew his name from the election. His foreign minister, Federico Gamboa, ran instead. The U.S. was happy about Gamboa's candidacy. They supported the idea of a new government, but not Huerta himself. The U.S. tried to get revolutionary leaders, like Venustiano Carranza, to support a new Gamboa government. Carranza refused.

Civil War and U.S. Intervention

Many rebellions broke out against Huerta's government. These were mostly in the North (Sonora, Chihuahua, and Coahuila). The U.S. allowed weapons to be sold to these revolutionaries. Fighting continued in Morelos under Emiliano Zapata, but the U.S. was not involved there.

Mexico fell into a civil war. The U.S. supported the revolutionary groups in the north. Other foreign powers, like Great Britain and Germany, also influenced the situation.

U.S. agents found out that a German ship, the Ypiranga, was carrying weapons to Huerta. President Wilson ordered troops to the port of Veracruz to stop the ship. The U.S. did not declare war. But U.S. troops fought against Huerta's forces in Veracruz. The Ypiranga managed to dock at another port, which angered Wilson.

On April 9, 1914, Mexican officials in Tampico arrested some U.S. sailors. One was taken from his ship, which the U.S. saw as U.S. territory. Mexico refused to apologize in the way the U.S. demanded. So, the U.S. Navy attacked Veracruz and occupied it for seven months. Wilson's real goal was to overthrow Huerta. The Tampico Affair helped weaken Huerta's government.

Argentina, Brazil, and Chile (the ABC Powers) helped resolve the conflict. They held a peace conference in Canada. U.S. troops then left Mexico. This stopped the conflict from becoming a full war.

U.S. and the Warring Revolutionary Groups (1914-1915)

After Huerta resigned and left Mexico, the revolutionary groups no longer had a common enemy. They tried to agree on how to govern Mexico. But this failed, and a civil war broke out among the winners. The U.S. still wanted to influence what happened in Mexico.

Events of 1916–1917

More border incidents happened in early 1916. On March 8, 1916, Pancho Villa and his men attacked Columbus, New Mexico. They burned army buildings and robbed stores. Fourteen soldiers and ten civilians were killed. In the U.S., Villa became known as a violent bandit.

General John J. Pershing quickly organized a mission to capture Villa. About 10,000 soldiers spent 11 months (March 1916 – February 1917) trying to find him. They did not capture Villa, but they did weaken his forces. Some of Villa's top commanders were caught or killed.

Pershing's orders required him to respect Mexico's independence. But the Mexican government and people were angry about the invasion. They demanded the U.S. troops leave. The U.S. troops went as far as Parral, about 400 miles south of the border. The campaign involved many small fights with rebel groups. There were even clashes with Mexican Army units. The most serious was the Battle of Carrizal on June 21, 1916.

War might have been declared, but the situation in Europe was critical (World War I). Most of the U.S. regular army was involved. Most of the National Guard was also sent to the border. Normal relations with Mexico were restored through talks. The troops left Mexico in February 1917.

The Zimmermann Telegram

Germany and the U.S. were rivals for influence in Mexico. As World War I continued, Germany worried the U.S. would join the British and French. Germany wanted to keep U.S. troops busy by starting a war between the U.S. and Mexico.

Germany sent a secret telegram. It outlined a plan to help Mexico in such a war. Mexico's reward would be to get back land lost to the U.S. in the Mexican–American War (1846–48). The British intercepted and decoded the Zimmermann Telegram. They gave it to President Wilson, who then made it public.

Carranza, whose group had received U.S. support, did not get involved in the conflict. Mexico stayed neutral during World War I. This helped Mexico act independently of both the U.S. and European powers.

Mexico's New Constitution

The Constitutionalists, who won power in 1915-16, wrote a new constitution. It was adopted in February 1917. This constitution worried foreign businesses. It allowed the Mexican government to take property if it was for the national good. It also claimed rights to resources underground, like oil. Foreign oil companies saw this as a threat. More radical revolutionaries pushed for these rules. However, Carranza did not put them into action. U.S. businesses wanted the U.S. government to protect their interests. But Wilson did not act on their behalf.

Border Clashes (1918–1919)

Small fights continued along the U.S.-Mexican border from 1917 to 1919. These were with Mexican irregulars and Federales (Mexican government troops). The Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917 increased tensions.

Military fights happened near Buenavista, Sonora, on December 1, 1917. They also occurred in San Bernardino Canyon, Chihuahua, on December 26, 1917. Other clashes were near La Grulla, Texas, on January 9, 1918. There were also fights at Pilares, Mexico, around March 28, 1918. A notable battle was at Nogales on the Sonora–Arizona border on August 27, 1918. Finally, there was a clash near El Paso, Texas, on June 16, 1919.

Foreigners Fighting in Mexico

Many adventurers from outside Mexico were drawn to the Mexican Revolution. They were attracted by the excitement and adventure. Most foreign fighters served in armies in northern Mexico. This was because these areas were closest to the U.S. Also, Pancho Villa was willing to hire mercenaries.

The first group of foreign fighters was the Falange de los Extranjeros (Foreign Phalanx). This was during the 1910 Madero revolt. It included Giuseppe Garibaldi II, a grandson of the famous Italian leader. Many American recruits were also part of this group.

Later, during the fight against Victoriano Huerta, many of these foreigners joined Pancho Villa's División del Norte. Villa hired Americans, Canadians, and others of all ranks. The most valued were machine gun experts like Sam Dreben. Artillery experts like Ivor Thord-Gray were also highly paid. Doctors for Villa's famous medical and mobile hospital corps were also important. Villa's "Legion of Honor" helped him succeed against Huerta's Federal Army.

U.S. Military Awards

The U.S. military gave the Mexican Service Medal to its troops who served in Mexico. The ribbon is yellow with a blue stripe in the middle. It also has a narrow green stripe on each edge. The green and yellow colors remember the Aztec standard from the Battle of Otumba in 1520. That standard had a gold sun with green quetzal feathers. The blue color represents the United States Army. It also refers to the Rio Grande river, which separates Mexico from the United States.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Participación de Estados Unidos en la Revolución mexicana para niños

In Spanish: Participación de Estados Unidos en la Revolución mexicana para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |