Corn smut facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Corn smut |

|

|---|---|

|

|

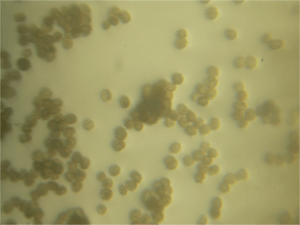

| Ustilago maydis diploid teleospores | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Ustilaginomycetes |

| Order: | Ustilaginales |

| Family: | Ustilaginaceae |

| Genus: | Ustilago |

| Species: |

U. maydis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ustilago maydis |

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

| Corn smut | |

|---|---|

Huitlacoche

|

|

| Common names | huitlacoche (Mexico), blister smut of maize, boil smut of maize, common smut of maize, corn truffle |

| Causal agents | Ustilago maydis |

| Hosts | maize and teosinte |

| EPPO Code | USTIMA |

| Distribution | Worldwide, where corn is grown |

Corn smut is a plant disease that affects maize (corn) and teosinte plants. It is caused by a special kind of fungus called Ustilago maydis. This fungus makes strange, tumor-like growths called galls on the corn plant.

Even though it's a disease, corn smut is actually eaten as a special food in Mexico. There, it's known as huitlacoche. People often use it as a filling in foods like quesadillas and other dishes made with tortillas, and sometimes in soups.

Contents

What is Huitlacoche?

In Mexico, corn smut is called huitlacoche. This name comes from an old language called Classical Nahuatl. Some people think the name means "sleeping excrescence," which refers to how the fungus grows on the corn and stops the kernels from developing. Other ideas for the name's meaning have also been suggested.

How Corn Smut Grows

The Ustilago maydis fungus infects all parts of the corn plant that grow above the ground. It especially likes to grow inside the corn kernels. When the fungus infects the kernels, they swell up into big, unusual galls. These galls look a bit like mushrooms.

These galls are made of swollen plant cells mixed with the fungus's threads and dark, blue-black spores. These dark spores make the corn cob look burned or scorched. This is why the fungus is named Ustilago, which comes from a Latin word meaning "to burn."

Corn Smut's Life Cycle

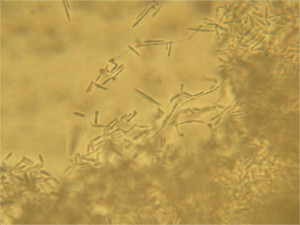

The fungus Ustilago maydis has an interesting life cycle. When it's grown in a lab, it acts like baker's yeast. It forms tiny, single cells called sporidia that multiply by budding.

When two of these sporidia meet on a corn plant, they join together. They then grow into a long thread-like structure called a hypha. This hypha enters the corn plant. Inside the plant, the fungus grows and causes the disease.

The fungus growing inside the plant leads to signs like yellowing leaves, changes in color, slower growth, and the growth of the tumors (galls) that hold the developing spores. When these galls are fully grown, they release their spores. Wind and rain then spread these spores. When the conditions are right, these spores can start the cycle all over again, infecting new corn plants.

How Plants Fight Back

Plants have ways to defend themselves against harmful microbes like fungi. One quick defense is to produce special oxygen molecules that can harm the invader. Ustilago maydis has ways to protect itself from this plant attack, which helps the fungus cause disease.

The fungus also has a good system to repair its own DNA. This repair system helps Ustilago maydis survive damage to its DNA. This damage can come from the plant's defenses or other things in the environment. This ability helps the fungus stay strong and keep infecting the corn.

Controlling Corn Smut

It's hard to control corn smut with regular sprays because the fungus infects individual kernels, not the whole cob. But there are other helpful ways to manage it:

- Resistant Plants: Using corn plants that are naturally strong against the fungus.

- Crop Rotation: Changing what crops you grow in a field each year. This helps because corn smut spores can stay in the soil.

- Avoid Plant Injury: Be careful not to hurt the corn plants. Cuts or scrapes can make it easier for the fungus to get inside.

- Clear Debris: Cleaning up old corn plant parts after harvest can help, as spores can live in them over winter.

- Nitrogen Levels: Too much nitrogen in the soil can make the infection worse. Using less nitrogen fertilizer can help.

Where Corn Smut Thrives

We don't know all the things that help Ustilago maydis grow, but some conditions make it thrive:

- Weather: Hot, dry weather during corn pollination, followed by heavy rain, seems to make the fungus more harmful.

- Soil: Too much fertilizer (especially nitrogen) in the soil can also increase the infection rate.

- Spore Spread: Strong winds and heavy rain help spread the spores of corn smut more easily.

- Human Actions: If old corn plant parts are not cleared away, the spores can survive the winter and infect new plants. Also, if people accidentally wound the corn plants, it gives the fungus an easy way to enter.

Economic Impact

While corn smut is a special food in some places, it can also cause problems for farmers. If corn gets infected, farmers can lose a lot of their harvest. For example, some studies show a 33% loss in corn yield due to corn smut. Since corn is a very important crop for both people and animals, this can affect food supplies.

Sweet corn is often the most affected. Besides losing part of their crop, farmers might find it hard to sell infected corn to people who don't know it's edible, because it looks unusual. This means farmers lose money. Also, corn with smut is harder to can or freeze.

However, in Mexico, corn smut is grown on purpose because it's a popular and expensive food called huitlacoche. This is one of the few times Ustilago maydis has a positive economic effect.

Culinary Uses

In Mexico, the infected galls of corn smut are highly valued as a special food called huitlacoche. They are often sold for a much higher price than regular corn. Eating corn smut started with the ancient Aztec cuisine.

For cooking, the galls are picked when they are still young and moist. If they get too old, they become dry and full of spores. When cooked, the young galls taste like mushrooms, with a sweet, savory, woody, and earthy flavor. They contain important nutrients like the amino acid lysine and more protein than most mushrooms.

It has been difficult to introduce corn smut into American and European diets because many farmers see it only as a disease. However, some chefs and groups have tried to promote it, sometimes calling it the "Mexican truffle" because of its unique taste and texture.

Native Americans, like the Zuni people, also used corn smut for traditional medicine.

Mexican Recipes

Huitlacoche can be used in many Mexican dishes. For example, a simple Mexican-style dish can be made with chorizo, onions, garlic, peppers, huitlacoche, and shrimp. The earthy flavors of the huitlacoche mix well with the other ingredients.

Another popular way to use huitlacoche is to add it to omelets. Its earthy taste blends with the eggs to create a flavor similar to truffles. It is also popular in quesadillas with Mexican cheese, cooked onions, and tomatoes.

When huitlacoche is cooked, its bluish color changes to black. It needs to be simmered slowly until it turns black and becomes a thick, oily paste.

Where to Find Huitlacoche

In Mexico, huitlacoche is mostly eaten fresh. You can buy it at restaurants, street markets, or farmer's markets. Sometimes, you can also find it canned in stores or online. Farmers in some areas even spread the spores on purpose to grow more of the fungus. They sometimes call it "hongo de maiz," which means "corn fungus."

Nutritional Value

When corn smut grows on a corn cob, it actually makes the corn more nutritious. Corn smut has much more protein than regular corn. It is also rich in the amino acid lysine, which corn usually has very little of.

See also

In Spanish: Carbón de la espiga para niños

In Spanish: Carbón de la espiga para niños