Aztec cuisine facts for kids

Aztec cuisine was the food eaten by the Nahua people of the Valley of Mexico before Europeans arrived in 1519. Their food was very healthy and provided all the important vitamins and minerals.

The most important food was maize (corn). It was so vital that it was a big part of their beliefs. Just like wheat in Europe or rice in Asia, a meal wasn't complete without it. Corn came in many colors and types. People ate it as corn tortillas, tamales, or ātōlli (corn gruel). Salt and chili peppers were also always present. If Aztecs were fasting, they would avoid these two foods.

Other main foods included beans, squash, and grains like amaranth and chia. These foods, along with corn, gave people a balanced diet. A special way of cooking corn called nixtamalization made it even more nutritious. This process involved soaking and cooking corn in an alkaline solution, which helped the body absorb more nutrients.

Water, corn gruels, and pulque (a fermented drink from the maguey plant) were common drinks. They also made alcoholic drinks from honey, cacti, and fruits. Important people like rulers and warriors preferred drinks made from cacao beans. These fancy drinks were often flavored with chili peppers, honey, and many other spices.

The Aztec diet included different kinds of fish and wild animals. They ate various birds, pocket gophers, green iguanas, axolotls (a type of water salamander), a small crayfish called acocil, and many kinds of insects, larvae, and insect eggs. They also raised turkeys, ducks, and dogs for food. Sometimes they ate meat from larger wild animals like deer, but this was not a main part of their diet. They also ate different mushrooms, including one that grows on corn called corn smut.

Squash was very popular and came in many types. Squash seeds, fresh or roasted, were a favorite snack. Tomatoes, though different from today's kinds, were often mixed with chili in sauces or used as fillings for tamales.

Contents

Meals

Most sources say Aztecs ate two meals a day. However, some workers might have had three meals: one at dawn, one around 9 AM, and one around 3 PM. It's not clear if drinking ātōlli (corn gruel) counted as a meal. Drinking a lot of thick ātōlli could provide as many calories as several tortillas, and most people drank it daily.

Feasts

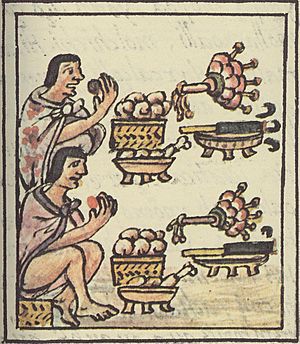

Aztec feasts and banquets were very ceremonial. Before a meal, servants offered fragrant tobacco tubes and flowers. Guests would rub these flowers on their heads, hands, and necks. Before eating, each guest would drop a little food on the ground as an offering to the god Tlaltecuhtli.

Table manners at feasts copied warrior movements. Smoking tubes and flowers were passed from the servant's left hand to the guest's right hand. Plates went from the servant's right hand to the guest's left hand. This was like how a warrior received his atlatl (spear-thrower) darts and shield.

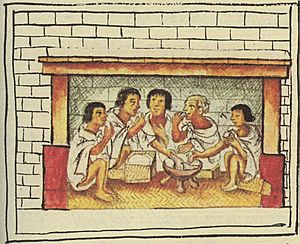

When eating, guests held small bowls of dipping sauce in their right hand. They dipped corn tortillas or tamales (served from baskets) with their left hand. Meals ended with chocolate, often served in a calabash cup with a stirring stick.

Men and women sat separately at banquets. It seems only men drank chocolate. Women likely drank pozolli (a corn gruel) or a type of pulque. Rich hosts often had guests in rooms around an open courtyard. Senior military men would perform dances. Festivities sometimes started at midnight, with some guests drinking chocolate and eating mushrooms to share their experiences.

Before dawn, people sang, and offerings were burned and buried in the courtyard to bring good luck to the host's children. At dawn, leftover flowers, tobacco tubes, and food were given to the elderly, the poor, or servants. Aztecs believed in balance, so at the end of a banquet, elders would remind the host to stay humble and not be too proud.

Domestic feasts

Private Aztec feasts included music, singing, storytelling, dancing, burning incense, flowers, tobacco, offerings, and gift-giving. These feasts showed off wealth and culture. Friars Bernardino de Sahagún and Diego Durán wrote that Aztec feasts had "everything in abundance." Feasts were very organized, almost like rituals, showing and strengthening social roles. Hosts had to provide well to avoid "offending" guests, and guests had to respect the host's status.

Many important events in Aztec society involved feasts. Child naming ceremonies included calling out the baby's name and then a big feast. This feast might have included bird or dog meat, tamales (meat or corn), beans, cacao beans, and roasted chilies.

Izcalli child presentation ceremonies were also important. Izcalli was the last month of the Aztec agricultural calendar. Every four years, the Izcalli celebration introduced children born during that period to the Aztec community. This feast taught children about religious life, like singing, dancing, and body modification. The food served was usually spicy. Sahagun noted that "when the good common folk ate, they sat about sweating, they sat about burning themselves."

Wedding ceremonies also had many feasts. When a young man wanted to marry, his parents had to ask permission from his school leaders. This process included a feast of tamales, chocolate, and sauces. The wedding itself had feasts with pulque, tamales, and turkey meat. Funerary feasts were also common among the wealthy. These feasts served octli (pulque), chocolate, bird, fruit, seeds, and other foods.

Public feasts

The 260-day Aztec ritual calendar included veintena, which were 20-day public ceremony periods. Each veintena was a complex festival with ceremonies for specific gods. Regional and local ceremonies differed from the official ones in Tenochtitlan. Food was a key part of veintena ceremonies; priests ate it and also used it for decoration. For example, during ceremonies for Xipe Totec, priests wore decorations made of "butterfly nets, fish banners, ears of maize, coyote heads made of amaranth seed, tortillas, thick rolls covered with a dough of amaranth seeds, toasted maize, red amaranth, and maize stalks with ears of green or tender maize."

In ceremonies for Mixcoatl, after a "great hunt," Aztecs feasted on deer, rabbit, and other hunted animals. Hunting was also important for celebrations dedicated to Xiuhtecuhtli, where boys and young men hunted for ten days. The hunted animals were given to priests, who cooked them in large fires.

Food preparation

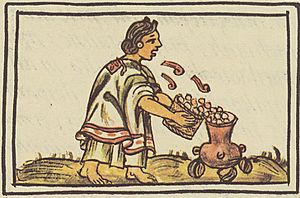

The main cooking method was boiling or steaming in two-handled clay pots called xoctli (or olla in Spanish). Ceramics were very important for cooking. They were used for preparing nixtamal, steaming tamales, and cooking beans, stews, and hot drinks. The xoctli was filled with food and heated over a fire. It could also steam food by putting a little water in the pot and placing tamales (wrapped in corn husks) on a light twig structure inside.

Tortillas, tamales, casseroles, and their sauces were the most common dishes. Chili and salt were everywhere. A basic meal was often just corn tortillas dipped in chilies ground with a little water. The corn dough could also wrap meat, sometimes even whole turkeys, before cooking.

In big Aztec towns, vendors sold all kinds of street food to both rich and poor. Besides ingredients and prepared food, you could buy every type of ātōlli, either to drink or as a quick liquid meal.

Women were in charge of cooking in Aztec society. Men generally did not cook. Kitchens were likely simple, single rooms separate from the main house. Most cooking probably happened on a small triangular hearth in the kitchen.

Kitchen tools

Most of what we know about Aztec cooking tools comes from finding the tools themselves, as they are rarely shown in art. Luckily, tools were often made of stone and ceramics, so many have been found in good condition.

Manos and metates were used to grind nixtamalized corn (nixtamal). They were also used to grind sauce ingredients like peppers, though different sets were likely used to keep flavors separate. A metate is a slightly curved stone slab. Nixtamal was placed on it, and a mano (a rough cylindrical stone) was rolled over it to grind the corn.

Manos and metates were used daily because ground nixtamal spoils quickly. Some studies suggest women spent hours grinding corn, but experienced women could do it in about an hour. Grinding with a metate is hard work. These tools remained popular in central Mexico because they grind finer than European mills, and tortillas made this way are still considered higher quality, even if they take more effort.

The molcajete is another grinding tool. It's a bowl made of porous basalt rock, with a basalt cylinder used to grind foods inside. It looks and works like a Western mortar and pestle. A molcajete was perfect for preparing sauces that might spill off a metate, and it could also be used as a serving dish.

Comals are ceramic griddles with a smooth top and porous bottom. They were used for cooking tortillas and other foods like peppers and roasted squash. Comals might also have been used as makeshift pot lids.

Spanish writers mentioned frying, but it seems Aztec frying involved syrup, not cooking fat. There's no evidence of large-scale vegetable oil production or frying pans found by archaeologists.

Foods

Aztec staple foods included maize, beans, and squash. They often added chilies, nopales (prickly pear cactus pads), and tomatoes. All these are still important in Mexican food today. They harvested acocils, a small crayfish from Lake Texcoco, and Spirulina algae. The algae was made into a cake called tecuitlatl, rich in flavonoids. Although the Aztec diet was mostly plant-based, they ate insects like grasshoppers (chapulín in singular), maguey worms, ants, and larvae. Insects have more protein than meat and are still a delicacy in parts of Mexico.

Cereals

Maize was the most important food for the Aztecs. Everyone ate it at every meal, and it was central to their myths. Some early Europeans heard Aztecs describe maize as "precious, our flesh, our bones."

It came in many varieties of different sizes, shapes, and colors: yellow, reddish, white with stripes, black, speckled, and a blue-husked type considered very special. Maize was so respected that women would blow on it before cooking so it wouldn't "fear the fire." Any dropped maize was picked up, not wasted. An Aztec person told a Spanish writer, Bernardino de Sahagún:

Our sustenance suffers, it lies weeping. If we should not gather it up, it would accuse us before our Lord. It would say: O our Lord, this vassal picked me not up when I lay scattered on the ground. Punish him. Or perhaps we should starve.

A process called nixtamalization was used across America where maize was a main food. The word comes from Nahuatl words for "ashes" and "unformed corn dough." This process is still used today. Dry corn grains are soaked and cooked in an alkaline solution, usually limewater. This removes the outer hull of the grains and makes the corn easier to grind.

Nixtamalization turns corn from just a source of carbohydrates into a much more complete food. It increases the amount of calcium, iron, copper, and zinc. It also makes niacin, riboflavin, and more protein (which humans can't normally digest from corn) available. Another benefit is that it stops the growth of certain toxic fungi. If the processed corn, nextamalli, is allowed to ferment, even more nutrients, like amino acids such as lysine and tryptophan, become available. With beans, vegetables, fruit, chilies, and salt, nixtamalized corn makes a healthy and varied diet.

Spices

Aztecs used many herbs and spices to flavor food. Chili peppers were among the most important. They came in many types, some grown and many wild. They varied greatly in how hot they were, from mild to very spicy. Chilies were often dried and ground for storage and cooking. Some were roasted first to give different flavors. Their tastes ranged from sweet and fruity to earthy, smoky, and fiery.

Native plants used as seasonings had flavors similar to Old World spices. Culantro (Mexican coriander) has a stronger flavor than cilantro. Mexican oregano and Mexican anise taste like their Mediterranean relatives. Allspice smells like a mix of nutmeg, cloves, and cinnamon.

The bark of canella (white cinnamon) has a soft flavor. Before onions and garlic arrived, Aztecs used similar wild plants like Kunth's onion and garlic vine leaves. Other flavorings included mesquite, vanilla, achiote, epazote, hoja santa, popcorn flower, and avocado leaf.

Dietary norms

The Aztecs believed in moderation in all parts of life. European writers were often impressed by their simple and moderate eating habits. Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, a bishop in the 1640s, wrote:

I have seen them eat with great deliberation, silence, and modesty, so that one knows that the patience shown in all of their habits is shown in eating as well, and they do not allow themselves to be rushed by hunger or the urge to satisfy it.

Fasting

For Aztecs, fasting mainly meant not eating salt and chilies. Everyone in Aztec society fasted to some extent. There were no regular exceptions, which surprised early Europeans. Even rulers like Moctezuma II were expected to fast and did so seriously. Sometimes he would avoid luxuries and eat only simple cakes of michihuauhtli and seeds of amaranth or goosefoot. His chocolate drink was replaced with water mixed with bean powder.

During the fourteenth month, called Quecholli, there was a large hunt as part of ceremonies for the hunting god Mixcoatl. To prepare, Aztecs would fast for five days. This fasting was done, according to Sahagun, "for the deer, so that it would be a successful hunt."

During celebrations for the god Tezcatlipoca, his priests fasted for ten, five, or seven days before the main feasts. They were known as "those who do penance." During festivals for Chicomecoatl, there would be times of heavy eating followed by fasting, sometimes making people ill.

Food and politics

Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote about how the ruler of Tenochtitlan was served food:

His cooks had more than thirty styles of dishes made according to their fashion and usage, and they put them on small low clay braziers so that they would not get cold ... if it was cold they made him a fire of glowing coals made from the bark of certain trees ... the odor of the bark ... was most fragrant ... they put the tablecloths of white fabric ... They served him on Cholula pottery, some red and some black ... and from time to time they brought him some cups of fine gold, with a certain drink made of cacao.

Sahagun listed the different types of tlaquetzalli, a chocolate drink served to Aztec lords:

The ruler was served his chocolate, with which he finished [his repast] - green, made of tender cacao; honeyed chocolate made with ground-up dried flowers - with green vanilla pods; bright red chocolate; orange-colored chocolate; rose-colored chocolate; black chocolate; white chocolate."

Aztec expansion often aimed to gain or keep access to foods needed for ceremonies and daily life. A leader's ability to get food for rituals was important for his political success.

See also

In Spanish: Gastronomía mexica para niños

In Spanish: Gastronomía mexica para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |