Mexican Inquisition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in New Spain |

|

|---|---|

| History | |

| Established | 4 November 1571 |

| Disbanded | 10 June 1820 |

| Leadership | |

|

First Inquisitor

|

|

|

Last Inquisitor

|

Manuel de Flores

|

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| Palace of the Inquisition, Mexico City | |

| Footnotes | |

| See also: Spanish Inquisition Peruvian Inquisition |

|

The Mexican Inquisition was like a branch of the Spanish Inquisition that operated in New Spain, which is now Mexico. When Spain conquered the Aztec Empire, it was a big political and religious change. In the 1500s, many religious changes were happening in Europe, including the Protestant Reformation and the Counter-Reformation. The rulers of Spain, known as the Catholic Monarchs, had just won back land from Muslim rule. This gave them special power to spread Catholicism, especially to the native peoples of Mesoamerica.

When the Inquisition came to the New World, it was used for similar reasons as in Europe. It targeted certain groups of people, though not as much the Indigenous people. Most of the official actions of the Inquisition happened in Mexico City. The Inquisition had its own building, which is now the Museum of Medicine. The official period of the Mexican Inquisition lasted from 1571 to 1820. Historians believe about 50 people were executed during this time.

Contents

Spanish Catholic Beliefs

The Mexican Inquisition was a continuation of what was happening in Spain. Spanish Catholicism had become very strict under Queen Isabella I of Castile (1479–1504). She created the Holy Office of the Inquisition in 1478 with permission from Pope Sixtus IV. This group combined government and religious power. Spain's strong desire to spread Catholicism came from its history of taking back land from Muslim control during the Reconquista. After discovering and conquering the New World, the Spanish believed they should teach non-Christians what they saw as the "true faith."

Bringing Christianity to New Spain

The Spanish crown had complete control over political and religious matters in New Spain. Popes Pope Alexander VI (in 1493) and Pope Julius II (in 1508) gave the Spanish rulers great power to convert Indigenous peoples to Catholicism. Spanish officials chose religious leaders in Mexico and could even reject orders from the Pope there. The effort to convert people and later the Inquisition also had political goals. Converting people to Christianity helped weaken the traditional power of the tlatoani, who were the chiefs of the native city-states.

Franciscan friars started working to spread Christianity in the 1520s. This continued under the first Bishop of Mexico, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, in the 1530s. Many Franciscans learned native languages and wrote down a lot about native culture. This gives us much of our knowledge about life in Mesoamerica. The Dominicans arrived in 1525. They were known as thinkers and also as agents of the Inquisition, just like in Spain. These two groups, along with the Augustinians, did most of the conversion work in Mexico. By 1560, these three groups had over 800 clergy members in New Spain. The Jesuits arrived in 1572. The number of Catholic clergy grew to 1,500 by 1580 and 3,000 by 1650. At first, the clergy focused on converting Indigenous peoples. Later, conflicts between religious groups and parts of European society became more important than conversion.

Three important church meetings took place in the 1500s to shape the new Church in New Spain. In 1565, the Second Mexican Ecclesiastical Council met to decide how to follow the rules from the Council of Trent (1546–1563). The Catholicism brought to New Spain was very strict and demanded complete agreement from believers. It focused on everyone following church rules and practices, rather than on individual beliefs. This strict and group-focused approach was brought to the Americas throughout the 1500s.

This group-focused approach allowed some flexibility in converting Native Americans. Many of their outward practices were similar to Catholic ones. Both systems mixed religious and government power. Both had a type of baptism where children were renamed. The Catholic practice of communion also had similarities to Aztec rituals involving eating replicas of their gods. Franciscan and Dominican studies of Native American culture and language led to some understanding of it. Unlike Islam, which the Spanish had fought against, Indigenous religions were called "paganism." However, they were seen as real religious experiences that had been changed by evil influences. Many similarities were found between native gods and Catholic saints or the Virgin Mary. Because of this, the conversion effort did not directly attack native beliefs. Instead, missionaries tried to guide existing beliefs toward Christian ideas. While Christianity was supposed to be supreme, the Church did not oppose practices that did not directly conflict with its teachings.

Native people found it easier to accept parts of Catholicism that were similar to their old beliefs. This included the idea of mixing religious and government power. Many European and Indigenous practices continued side-by-side. Old Indigenous practices were given Christian names and meanings. So, pre-Hispanic beliefs and practices lived on in the new religion and influenced how it was expressed. A famous example is the rise of the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Franciscan Fray Bernardino de Sahagún thought it was a post-conquest version of the Aztec cult of Tonatzin, a mother goddess. However, the archbishop of Mexico, Fray Alonso de Montúfar, who was a Dominican, supported the cult. Some even thought that the Nahua god Quetzalcoatl was being seen as the Apostle Thomas in the early colonial period.

However, not all native reactions were peaceful. There was strong resistance early on in Tlaxcala. The Oaxaca sierra region fought back violently until the late 1550s. The Otomi and people in parts of Michoacán state also resisted as late as the 1580s.

Inquisition by Bishops

When the New World was discovered and conquered, Cardinal Adrian de Utrecht was the head Inquisitor in Spain. He appointed Pedro de Córdoba as Inquisitor for the West Indies in 1520. He also had Inquisition powers in Mexico after the conquest, but not the official title. When Franciscan Juan de Zumárraga became the first Bishop of Mexico in 1535, he used Inquisition powers as a bishop.

One of Bishop Zumárraga's first actions as an inquisitor was in 1536. He prosecuted a Nahua man named Martín, whose Indigenous name was Ocelotl. He was accused of being a nahualli (a priest with special powers) and for other religious offenses. The records of his trial were published in 1912. This early case against a Nahua holy man got a lot of attention from scholars.

Another important case by Bishop Zumárraga was against a Nahua lord from Texcoco, who was baptized as Carlos. He is known as Don Carlos Ometochtzin. The trial records were published in 1910 and are the main source for this famous case. Don Carlos was likely a nephew of Nezahualcoyotl. Zumárraga accused this lord of returning to worship the old gods. After a trial with Indigenous witnesses and Don Carlos's own statements, the Texcocan lord was found guilty. He was executed on November 30, 1539. However, Spanish officials did not think this prosecution was a good idea. Zumárraga himself was criticized for it.

For several reasons, the persecution of Indigenous people for religious offenses was not strongly pursued. First, many native practices had similarities to Christianity. Also, this "paganism" was not the same as the Jewish or Islamic faiths that Spanish Christians had fought against so fiercely. So, church leaders chose to guide native practices toward Christian ways instead. Also, many friars sent to convert native peoples became their protectors from the very harsh treatment by government officials. The lighter treatment of Indigenous peoples was very different from how European people accused of religious offenses were treated later. It was also probably not wise to strictly enforce church rules where native peoples greatly outnumbered their European conquerors, who also needed to rule through native leaders.

These reasons help explain why the Inquisition was not officially established in New Spain until 1571. However, this does not mean that Inquisition-like methods were never used after Don Carlos's execution. Resistance by the Maya in the Yucatán in 1546–1547 led to more aggressive conversion efforts. The Franciscans found that many traditional beliefs and practices still existed despite their efforts. Under Fray Diego de Landa, the Franciscans decided to make an example of Indigenous people they considered to have gone back to old ways. They did this without proper legal steps. Many people were tortured, and as many of the Maya's sacred books as could be found were destroyed.

Accusations of Magic and Power

While many people were accused and some executed for secretly practicing other faiths, a large number of cases brought to the Inquisition involved magic or sorcery. This was seen as going against Christian beliefs and working with evil. Most of these cases were against women, though some men were also accused.

In Spain, the Inquisition usually wasn't very interested in accusations of witchcraft. But in Spanish America, Inquisitors were concerned with discrediting women who were accused of and admitted to magic. Some upper-class women tried to avoid being found guilty by saying that the magic they were accused of was just a female delusion. While this worked somewhat for elite women, the prosecution of these women actually created a situation where lower- and middle-class women could claim unusual abilities. This gave them some power in their local communities.

In communities with mixed ethnic groups, the types of "magic" women in Hispanic America often used were a folk version of Catholicism. These practices were influenced by Spanish, Indigenous, and African traditions. Using "everyday magic" was not uncommon. Some types of magic were called "sorcery," which some authors define as needing a pact with evil. Other "magical practices" that did not require such a pact were very diverse and depended on a person's background and social status. These types of magic were used by people who were oppressed. Many enslaved people used magic or strong words against Christian beliefs as a way to show power against their masters. It was a way to gain some control. By using magic, they felt they could cause bad things to happen to their masters. Enslaved people would often use strong words against Christian beliefs as a chance to speak with Inquisitors and complain about their masters.

For women, across different social classes and backgrounds, a goal of magic was often to change the power balance in marriage or to find a husband. Sometimes this was simple magic meant to make a husband stay loyal to his wife. This approach played on strict rules about a woman's place in the home. It also represented a way for women to gain power over their husbands.

Sometimes the idea of magic or special powers did not involve Christian ideas of evil, but rather ideas about Jesus and God. A woman who claimed a special connection to Christ could improve her social and economic standing. People in her community might come to her for advice and help. Even wealthy men might want to spend time with such women to gain insights. An example is Marina de San Miguel, who was brought before the Mexican Inquisition in 1599. Marina, a deeply religious woman, was known in her neighborhood for having religious experiences where she communicated with saints and Christ. Because of this, members of her community, religious people, and even clergy would come to Marina for advice.

It is important to note that while many women from lower or middle-class backgrounds could use ideas of magic and evil pacts to create a sense of power, some women experienced the opposite. When women used these magic practices, they were often so moved by the "evil" of their actions that they would confess. They would come before Inquisitors crying and were often forgiven for their actions.

The Colonial Holy Office of the Inquisition

When the Holy Office of the Inquisition was set up in New Spain in 1571, it did not have power over Indigenous people, except for materials printed in Indigenous languages. Its first official Inquisitor was Archbishop Pedro Moya de Contreras. He created the "Tribunal de la Fe" (Tribunal of the Faith) in Mexico City. Through this office, he brought the rules of the Inquisition from Spain to Mexico. However, the Inquisition's full power was felt by non-Indigenous populations, such as people of African descent and even some Europeans. Historian Luis González Obregón estimates that 51 death sentences were carried out during the 235–242 years the tribunal was officially active. However, records from this time are incomplete, so exact numbers cannot be confirmed.

One group that faced difficulties were people of Portuguese descent who were accused of secretly practicing Judaism. Jewish people who refused to convert to Christianity had been expelled from Spain in 1492 and from Portugal in 1497. When Spain and Portugal later united, many Portuguese people who had converted to Christianity came to New Spain looking for business opportunities. After one person confessed, many of his relatives and other merchant families in Mexico City came under suspicion. In 1642, 150 of these people were arrested within a few days. The Inquisition began a series of trials. These people were accused of still practicing Judaism. Many of them were merchants involved in important activities in New Spain. On April 11, 1649, the government held the largest ever public punishment ceremony (called an auto da fe) in New Spain. Twelve of the accused were executed by strangulation and then burned. One person, Tomás Treviño de Sobremontes, was burned alive because he refused to give up his Jewish faith. The Inquisition also tried people who had already died, removing their bones from Christian burial grounds. At the large Auto de Fe of 1649, these deceased people were symbolically burned, along with their remains.

A well-known case was that of Luis de Carabajal y Cueva. He was born in Portugal in 1537. He moved to New Spain and became a businessman and soldier. He fought for the Spanish against Indigenous groups. He brought many of his family members from Spain to live in Nuevo Leon. It was rumored that his family secretly practiced Jewish customs. He was brought before the Inquisition and faced many accusations, but the main one was returning to the Jewish faith. He was found guilty in 1590 and sentenced to six years of exile from New Spain, but he died before this could happen. Later, on December 8, 1596, most of his extended family, including his sister Francisca and her children, were tortured and executed in Mexico City.

Another case was that of Nicolas de Aguilar. Aguilar was a mestizo, meaning he had both Spanish and Indigenous (Purépecha) heritage. He was a government official in New Mexico. He tried to protect the Tompiro Indigenous people from mistreatment by Franciscan priests. In 1662, due to complaints from the Franciscans, he was arrested and accused of religious offenses. He defended himself strongly in Mexico City but was found guilty. He was sentenced to a public punishment ceremony and banned from New Mexico for 10 years and from government service for life.

After many accusations, authorities arrested 123 people in 1658 for suspected homosexuality. Although 99 of them managed to disappear, the Royal Criminal Court sentenced fourteen men to death by public burning. These sentences were carried out on November 6, 1658. Records from these trials and others in 1660, 1673, and 1687 suggest that Mexico City had an active gay community at that time.

Another group that had to be careful during this time were scholars. In the 1640s and 1650s, the Inquisition stopped early attempts to update school subjects. Educators were trying to keep up with new ideas from Europe. The main target was Fray Diego Rodriguez (1569–1668). He became the first professor of Mathematics and Astronomy at the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico in 1637. He tried to introduce the scientific ideas of Galileo and Kepler to the New World. For thirty years, he argued that religious studies should be separate from science. He led a small group of academics who secretly met to discuss new scientific ideas. However, political struggles in the 1640s brought them under the Inquisition's suspicion. Investigations and trials followed until the mid-1650s. When academics tried to hide books that the Holy Office banned in 1647, the Inquisition made all six booksellers in the city show their lists of books. If they refused, they faced fines and being kicked out of the church.

A unique and dramatic case was that of an Irishman named William Lamport. He pretended to be Don Guillén de Lombardo, the secret half-brother of King Philip IV. He tried to start a rebellion in Mexico City and have himself named king. This would-be king was reported to the Inquisition in 1642 and was executed in 1659. Some consider him a person who helped inspire Mexican Independence. There is a statue of him inside the base of the Monument to Independence in Mexico City.

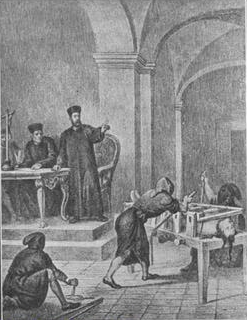

Those found guilty by the Inquisition usually received some form of punishment. The most severe punishment was execution, which happened in a ceremony called the auto de fe. Almost all of these ceremonies took place in Mexico City. For these events, important people and most of the public would attend in their best clothes. The Church set up a stage with pulpits and fancy furniture for the noble guests. Tapestries and fine cloth decorated the stage. No expense was spared to show the power of the church leaders. Also, all nobles, including the viceroy and his court, and other authorities, would be clearly present. The ceremony began with a sermon and a long statement about what the true faith was. Everyone present had to swear to this. The condemned people were led onto the stage wearing special capes that showed their crime and punishment. They also wore a tall, pointed hat. Then the sentences were carried out.

The Inquisition officially continued until the early 1800s. It was first ended by a law in 1812. However, political problems led to its brief return between 1813 and 1820. It was finally abolished in 1820.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Inquisición en Nueva España para niños

In Spanish: Inquisición en Nueva España para niños

- Converso

- Morisco

- Crypto-Islam

- Crypto-Judaism

- Judaizer

- Limpieza de sangre

- Marrano

- New Christian

- Palace of Inquisition

- Peruvian Inquisition

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |