Roman–Persian Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Roman–Persian Wars |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

Roman Republic, succeeded by Roman Empire and Eastern Roman Empire |

Parthian Empire, succeeded by Sasanian Empire |

||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

Clients/allies

Hyrcanus II (POW)

Phasael (POW) Herod Artavasdes II of Armenia Tigranes VI of Armenia Antiochus IV of Commagene Polemon II of Pontus Aristobulus of Chalcis Parthamaspates of Parthia Sanatruq II Arshak II of Armenia Mushegh I Mamikonian Pharas the Herulian Odaenathus Gubazes I of Lazica Vakhtang I of Iberia Jabalah IV ibn al-Harith † Gubazes II of Lazica Tzath I of Lazica Al-Harith ibn Jabalah Al-Mundhir III ibn al-Harith Ziebel |

Clients/allies

Quintus Labienus

Antigonus II Mattathias Artavasdes I of Media Atropatene Tiridates I of Armenia Monobazus II of Adiabene Meharaspes of Adiabene Mirian III of Iberia 'Amr ibn Imru' al-Qays Grumbates Urnayr of Caucasian Albania Al-Mundhir I ibn al-Nu'man Al-Mundhir III ibn al-Nu'man Gubazes II of Lazica Al-Mundhir IV ibn al-Mundhir (POW) Stephen I of Iberia † Nehemiah ben Hushiel Benjamin of Tiberias |

||||

The Roman–Persian Wars were a long series of fights between the Greco-Roman world and two powerful Iranian empires: the Parthians and later the Sasanians. These wars lasted for over 700 years, from 54 BC to 628 AD. They involved the Roman Republic, then the Roman Empire (which later became the Eastern Roman Empire), and the Parthian Empire, followed by the Sasanian Empire.

Many smaller kingdoms and allied nomadic groups also took part in these conflicts. They often acted as buffer states or fought as proxies for the larger empires. The wars finally ended when the early Muslim conquests began. These new invasions led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire and big losses of land for the Byzantine Empire.

Even though the fighting went on for centuries, the border between the Roman and Persian empires stayed mostly the same. It was like a game of tug of war. Cities, forts, and provinces were constantly attacked, captured, destroyed, and traded back and forth. Neither side had enough supplies or soldiers to keep fighting far from their own lands. This meant they couldn't push too far without risking their own borders.

Both empires did manage to conquer lands beyond their borders. But over time, things usually went back to how they were before. At first, their armies used different fighting styles. However, they slowly learned from each other. By the 500s AD, their armies were very similar and equally strong.

The huge cost of these wars was terrible for both empires. The long and growing conflicts in the 500s and 600s left them tired and weak. This made them easy targets for the sudden rise of the Rashidun Caliphate (Muslim armies). These forces attacked both empires just a few years after the last Roman–Persian war ended.

Because the Romans and Persians were so weak, the Rashidun armies quickly conquered the entire Sasanian Empire. They also took away many lands from the Eastern Roman Empire. These included Syria, the Caucasus, Egypt, and North Africa. In the centuries that followed, even more of the Eastern Roman Empire came under Muslim rule.

Contents

- How the Wars Began: A Look Back

- Roman Republic vs. Parthian Empire Conflicts

- Roman Empire vs. Parthian Empire Conflicts

- Roman Empire vs. Sasanian Empire Conflicts

- Byzantine-Sasanian Wars: Later Conflicts

- What Happened After the Wars

- Fighting Styles and Strategies

- Why These Wars Mattered

- How We Know About These Wars

- Images for kids

- See also

How the Wars Began: A Look Back

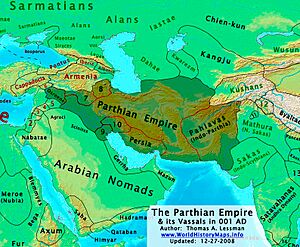

From the 200s BC to the 600s AD, the main powers in the East were large empires. They had managed to create stable territories that crossed different regions. The Romans and Parthians met because they both conquered parts of the Seleucid Empire.

In the 200s BC, the Parthians moved from Central Asia into northern Iran. For a while, the Seleucids controlled them. But in the 100s BC, the Parthians broke free. They built an independent state that grew steadily. They took land from their former rulers. By the 200s and early 100s BC, they had conquered Persia, Mesopotamia, and Armenia.

The Parthians were ruled by the Arsacid dynasty. They fought off several Seleucid attempts to get their lands back. They also set up related ruling families in the Caucasus. These included the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia, Arsacid dynasty of Iberia, and Arsacid dynasty of Caucasian Albania.

Meanwhile, the Romans drove the Seleucids out of their lands in Anatolia in the early 100s BC. This happened after they defeated Antiochus III the Great in battles like Thermopylae and Magnesia. Finally, in 64 BC, the Roman general Pompey conquered the last Seleucid lands in Syria. This ended the Seleucid state. It also moved the Roman eastern border to the Euphrates River, where it met the Parthian territory.

Roman Republic vs. Parthian Empire Conflicts

The Parthians started expanding into the West during the time of Mithridates I. This expansion was continued by Mithridates II. He tried to make an alliance with the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla around 105 BC, but it didn't work out.

When the Roman general Lucullus invaded Southern Armenia and attacked Tigranes in 69 BC, he asked Phraates III not to get involved. The Parthians stayed neutral, but Lucullus still thought about attacking them. In 66–65 BC, Pompey made a deal with Phraates. Roman and Parthian troops invaded Armenia. But soon, they argued about the Euphrates River as a border. In the end, Phraates took control of Mesopotamia, except for the western area of Osroene. This area became a Roman dependency.

The Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus led an invasion of Mesopotamia in 53 BC. It was a disaster. He and his son Publius were killed at the Battle of Carrhae by the Parthians, led by General Surena. This was one of the worst Roman defeats since the battle of Arausio. The Parthians raided Syria the next year. They launched a big invasion in 51 BC. But their army was caught in a trap near Antigonea by the Romans and forced to retreat.

The Parthians mostly stayed neutral during Caesar's Civil War. This war was fought between supporters of Julius Caesar and those of Pompey and the Roman Senate. However, they kept ties with Pompey. After Pompey's defeat and death, a force led by Pacorus I helped the Pompeian general Q. Caecilius Bassus. Bassus was under attack at Apamea Valley by Caesar's forces.

Once the civil war ended, Julius Caesar planned a campaign against Parthia. But his assassination stopped the war. The Parthians supported Brutus and Cassius during the Liberators' civil war. They sent soldiers to fight with them at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC.

After Brutus and Cassius were defeated, the Parthians invaded Roman territory in 40 BC. They joined forces with the Roman Quintus Labienus, who had supported Brutus and Cassius. They quickly took over the Roman province of Syria. They then moved into Judea. They removed the Roman client ruler Hyrcanus II and put his nephew Antigonus in charge. For a short time, it seemed like the whole Roman East might be lost to the Parthians.

However, the end of the second Roman civil war soon brought Roman strength back to Asia. Mark Antony sent Ventidius to fight Labienus, who had invaded Anatolia. Labienus was soon pushed back to Syria by Roman forces. Even with Parthian help, he was defeated, captured, and killed. After another defeat near the Syrian Gates, the Parthians left Syria. They returned in 38 BC but were completely defeated by Ventidius, and Pacorus was killed. In Judaea, Antigonus was removed with Roman help by Herod in 37 BC.

With Roman control of Syria and Judaea restored, Mark Antony led a huge army into Atropatene. But his siege equipment and its guards were cut off and destroyed. His Armenian allies also left him. Antony failed to make progress against Parthian positions. The Romans retreated with many losses. Antony was in Armenia again in 33 BC to join the Median king against Octavian and the Parthians. Other problems forced him to leave, and the whole region came under Parthian control.

Roman Empire vs. Parthian Empire Conflicts

Tensions between the two powers threatened new war. So, Octavian and Phraataces made a deal in 1 AD. Parthia agreed to pull its forces out of Armenia. They also agreed to recognize Rome's control there. Still, Roman and Persian competition over Armenia continued for decades.

The Parthian King Artabanus III put his son on the empty Armenian throne. This started a war with Rome in 36 AD. It ended when Artabanus III gave up his claims to influence Armenia. War broke out again in 58 AD. This happened after the Parthian King Vologases I forced his brother Tiridates onto the Armenian throne. Roman forces removed Tiridates and put a prince from Cappadocia in his place. This led to an inconclusive war (a war with no clear winner). It ended in 63 AD. The Romans agreed to let Tiridates and his family rule Armenia. But they had to receive their kingship from the Roman emperor.

A new series of conflicts began in the 100s AD. During this time, the Romans usually had the upper hand over Parthia. Emperor Trajan invaded Armenia and Mesopotamia in 114 and 115 AD. He made them Roman provinces. He captured the Parthian capital, Ctesiphon. Then he sailed downriver to the Persian Gulf.

However, revolts started in 115 AD in the Parthian lands that Rome had taken. Also, a big Jewish revolt broke out in Roman territory. This severely stretched Rome's military resources. Parthian forces attacked important Roman places. The Roman garrisons (military bases) at Seleucia, Nisibis, and Edessa were driven out by the local people. Trajan put down the rebels in Mesopotamia. But after putting the Parthian prince Parthamaspates on the throne as a client ruler, he pulled his armies back to Syria. Trajan died in 117 AD. He was not able to fully organize and strengthen Roman control over the Parthian provinces.

Trajan's Parthian War changed Rome's overall military plan. But his successor, Hadrian, decided it was better for Rome to make the Euphrates River its direct border again. Hadrian went back to the way things were before the war. He gave back the lands of Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Adiabene to their previous rulers and client-kings.

War over Armenia started again in 161 AD. Vologases IV defeated the Romans there. He captured Edessa and attacked Syria. In 163, a Roman counter-attack led by Statius Priscus defeated the Parthians in Armenia. He put a Roman-favored ruler on the Armenian throne. The next year, Avidius Cassius invaded Mesopotamia. He won battles at Dura-Europos and Seleucia. He also sacked Ctesiphon in 165. A disease, possibly smallpox, was spreading through Parthia at the time. It spread to the Roman army and forced them to retreat. This was the start of the Antonine Plague. It raged for a generation across the Roman Empire.

In 195–197, a Roman attack led by Emperor Septimius Severus resulted in Rome gaining northern Mesopotamia. This included areas around Nisibis and Singara. Ctesiphon was sacked for the third time. A final war against the Parthians was started by Emperor Caracalla. He sacked Arbela in 216. After he was killed, his successor, Macrinus, was defeated by the Parthians near Nisibis. To get peace, he had to pay for the damage Caracalla had caused.

Roman Empire vs. Sasanian Empire Conflicts

Early Roman-Sasanian Fights

Fighting started again soon after the Parthian rule was overthrown. Ardashir I founded the Sasanian Empire. Ardashir (ruled 226–241) raided Mesopotamia and Syria in 230. He demanded that Rome give back all the lands that used to belong to the Achaemenid Empire. After talks failed, Alexander Severus marched against Ardashir in 232. One part of his army went into Armenia. Two other parts operated to the south but failed. In 238–240, near the end of his rule, Ardashir attacked again. He took several cities in Syria and Mesopotamia, including Carrhae, Nisibis, and Hatra.

The struggle continued and became more intense under Ardashir's successor, Shapur I. He invaded Mesopotamia and captured Hatra. Hatra was a buffer state that had recently changed its loyalty. But Shapur's forces were defeated in a battle near Resaena in 243. Carrhae and Nisibis were taken back by the Romans. Encouraged by this success, Emperor Gordian III moved down the Euphrates. But he was defeated near Ctesiphon in the Battle of Misiche in 244. Gordian either died in the battle or was killed by his own soldiers. Philip became emperor. He quickly made a peace deal, paying 500,000 denarii to the Persians.

The Roman Empire was weakened by Germanic invasions and many short-term emperors. So, Shapur I soon started his attacks again. In the early 250s, Philip was fighting for control of Armenia. Shapur conquered Armenia and killed its king. He defeated the Romans at the Battle of Barbalissos in 253. Then he probably took and looted Antioch. Between 258 and 260, Shapur captured Emperor Valerian after defeating his army at the Battle of Edessa. He moved into Anatolia but was defeated by Roman forces there. Attacks from Odaenathus of Palmyra forced the Persians to leave Roman territory. They gave back Armenia and Antioch.

In 275 and 282, Aurelian and Probus planned to invade Persia. But they were both killed before they could carry out their plans. In 283, Emperor Carus launched a successful invasion of Persia. He sacked its capital, Ctesiphon. They probably would have conquered more if Carus had not died in December of the same year. His successor, Numerian, was forced by his own army to retreat. They were scared by the belief that Carus had died from a lightning strike.

After a short peaceful time during Diocletian's early rule, Narseh started fighting the Romans again. He invaded Armenia and defeated Galerius not far from Carrhae in 296 or 297. However, in 298, Galerius defeated Narseh at the Battle of Satala. He sacked the capital Ctesiphon and captured the Persian treasury and royal family. The peace deal that followed gave the Romans control of the area between the Tigris and the Greater Zab rivers. This Roman victory was the most decisive in many decades. All the lost territories, all the disputed lands, and control of Armenia were now in Roman hands. Many cities east of the Tigris were given to the Romans. These included Tigranokert, Saird, Martyropolis, Balalesa, Moxos, Daudia, and Arzan.

The agreements from 299 lasted until the mid-330s. Then, Shapur II began a series of attacks against the Romans. He won many battles, including defeating a Roman army led by Constantius II at Singara (348). But his campaigns had little lasting effect. Three Persian sieges of Nisibis, known as the key to Mesopotamia at that time, were pushed back. Shapur did succeed in 359 in capturing Amida and taking Singara. But both cities were soon taken back by the Romans.

After a quiet period in the 350s, while Shapur fought off nomad attacks on Persia's eastern and northern borders, he launched a new campaign in 359. He had the help of eastern tribes he had defeated. After a difficult siege, he again captured Amida (359). The next year, he captured Bezabde and Singara. He also pushed back the counter-attack of Constantius II. But the huge cost of these victories weakened him. He was soon abandoned by his barbarian allies. This left him open to a major attack in 363 by the Roman Emperor Julian. Julian advanced down the Euphrates to Ctesiphon with a large army.

Despite a tactical victory at the Battle of Ctesiphon outside the walls, Julian could not take the Persian capital or go any further. He retreated along the Tigris River. Harassed by the Persians, Julian was killed in the Battle of Samarra during a difficult retreat. With the Roman army stuck on the eastern bank of the Euphrates, Julian's successor Jovian made peace. He agreed to big concessions (giving up things) for safe passage out of Sasanian territory. The Romans gave up their former lands east of the Tigris, as well as Nisibis and Singara. Shapur soon conquered Armenia, which the Romans had abandoned.

In 383 or 384, Armenia again became a point of disagreement between the Roman and Sasanian empires. But no fighting happened. Both empires were busy with barbarian threats from the north. In 384 or 387, a final peace treaty was signed by Shapur III and Theodosius I. It divided Armenia between the two states. Meanwhile, the northern parts of the Roman Empire were invaded by Germanic, Alanic, and Hunnic peoples. Persia's northern borders were threatened first by Hunnic peoples and then by the Hephthalites.

With both empires busy with these threats, a mostly peaceful time followed. It was only broken by two short wars. The first was in 421–422. This happened after Bahram V punished high-ranking Persian officials who had become Christians. The second was in 440, when Yazdegerd II raided Roman Armenia.

Byzantine-Sasanian Wars: Later Conflicts

The Anastasian War (502–506 AD)

The Anastasian War ended the longest period of peace the two empires ever had. War started when the Persian King Kavadh I tried to get money by force from the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I. The emperor refused to give it. So, the Persian king tried to take it by force.

In 502 AD, Kavadh quickly captured the unprepared city of Theodosiopolis. He then attacked the fortress-city of Amida through the autumn and winter of 502–503. The siege of Amida was much harder than Kavadh expected. The defenders fought off Persian attacks for three months before they were defeated.

In 503, the Romans tried to besiege the Persian-held Amida, but failed. Kavadh invaded Osroene and attacked Edessa with the same result. Finally, in 504, the Romans took control by attacking Amida again, which led to the city's fall. That year, a ceasefire was agreed because Huns invaded Armenia from the Caucasus.

Even though the two powers talked, a treaty wasn't agreed until November 506. In 505, Anastasius ordered a large fortified city to be built at Dara. At the same time, old fortifications were also improved at Edessa, Batnae, and Amida. No more large-scale fighting happened during Anastasius's rule. But tensions continued, especially while work went on at Dara.

This was because an earlier treaty had forbidden building new forts in the border area. Anastasius continued the project despite Persian objections. The walls were finished by 507–508.

The Iberian War (526–532 AD)

In 524–525 AD, Kavadh suggested that Justin I adopt his son, Khosrau. But the talks soon broke down. The Roman emperor and his nephew, Justinian, liked the idea at first. However, Justin's chief legal officer, Proculus, was against it.

Tensions grew when the king of Iberia, Gourgen, switched to the Roman side. In 524/525, the Iberians rebelled against Persia. They followed the example of the Christian kingdom of Lazica nearby. The Romans hired Huns from the north of the Caucasus to help them.

At first, both sides preferred to fight through their allies. These were Arab allies in the south and Huns in the north. Open Roman–Persian fighting broke out in the Transcaucasus region and upper Mesopotamia by 526–527. The early years of the war favored the Persians. By 527, the Iberian revolt was crushed. A Roman attack against Nisibis and Thebetha that year failed. Forces trying to fortify Thannuris and Melabasa were stopped by Persian attacks.

To fix these problems, the new Roman emperor, Justinian I, reorganized his armies in the East. In 528, Belisarius tried to protect Roman workers in Thannuris. They were building a fort right on the border, but he failed. Damaging raids on Syria by the Lakhmids in 529 encouraged Justinian to strengthen his own Arab allies. He helped the Ghassanid leader Al-Harith ibn Jabalah turn a loose group into a strong kingdom.

In 530, a major Persian attack in Mesopotamia was defeated by Roman forces under Belisarius at Dara. A second Persian push in the Caucasus was defeated by Sittas at Satala. Belisarius was defeated by Persian and Lakhmid forces at the Battle of Callinicum in 531. This led to his dismissal. In the same year, the Romans gained some forts in Armenia. The Persians captured two forts in eastern Lazica.

Right after the Battle of Callinicum, talks between Justinian's envoy, Hermogenes, and Kavadh failed. A Persian siege of Martyropolis was stopped by Kavadh I's death. The new Persian king, Khosrau I, restarted talks in spring 532. They finally signed the Perpetual Peace in September 532. This peace lasted less than eight years. Both powers agreed to return all captured lands. The Romans agreed to make a one-time payment of 110 centenaria (11,000 pounds of gold). The Romans got back the Lazic forts. Iberia stayed in Persian hands. Iberians who had left their country could choose to stay in Roman territory or go back home.

The Lazic War (540–562 AD)

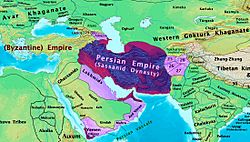

| Roman (Byzantine) Empire Acquisitions by Justinian | Sasanian Empire Sasanian vassals |

The Persians broke the "Treaty of Eternal Peace" in 540 AD. This was probably because Rome had taken back much of its former western empire. This was made easier by the end of the war in the East. Khosrau I invaded and destroyed Syria. He demanded large sums of money from cities in Syria and Mesopotamia. He also systematically looted other cities, including Antioch. Its people were taken to Persian territory.

Belisarius's successful campaigns in the west encouraged the Persians to go back to war. They took advantage of Rome being busy elsewhere. They also wanted to stop Rome from expanding its territory and resources. In 539, a Lakhmid raid led by al-Mundhir IV hinted at new fighting. This raid was defeated by the Ghassanids under al-Harith ibn Jabalah. In 540, the Persians broke the "Treaty of Eternal Peace." Khosrau I invaded Syria, destroying the great city of Antioch. He took its people to Weh Antiok Khosrow in Persia. As he left, he demanded large sums of money from cities in Syria and Mesopotamia. He also systematically looted key cities. In 541, he invaded Lazica in the north.

Justinian quickly called Belisarius back to the East to deal with the Persian threat. Meanwhile, the Ostrogoths in Italy, who were in contact with the Persian King, launched a counter-attack under Totila. Belisarius took the field and fought an inconclusive campaign against Nisibis in 541. In the same year, Lazica switched its loyalty to Persia. Khosrau led an army to secure the kingdom.

In 542, Khosrau launched another attack in Mesopotamia. He tried unsuccessfully to capture Sergiopolis. He soon retreated when an army under Belisarius arrived. On his way, he sacked the city of Callinicum. Attacks on several Roman cities were pushed back. The Persian general Mihr-Mihroe was defeated and captured at Dara by John Troglita.

An invasion of Armenia in 543 by Roman forces in the East, numbering 30,000, against the capital of Persian Armenia, Dvin, was defeated by a clever ambush by a small Persian force at Anglon. Khosrau besieged Edessa in 544 without success. He was eventually paid off by the defenders. The people of Edessa paid five centenaria to Khosrau. The Persians left after almost two months. After the Persian retreat, two Roman envoys, Constantinus and Sergius, went to Ctesiphon to arrange a truce with Khosrau. The war continued under other generals. It was also slowed down by the Plague of Justinian, which made Khosrau temporarily leave Roman territory. A five-year truce was agreed to in 545. Rome secured it by making payments to the Persians.

Early in 548, King Gubazes of Lazica found Persian protection difficult. He asked Justinian to bring back Roman protection. The emperor took the chance. In 548–549, combined Roman and Lazic forces with the general Dagisthaeus won many victories against Persian armies. However, they failed to take the important fort of Petra. In 551 AD, general Bessas, who replaced Dagistheus, brought Abasgia and the rest of Lazica under control. He finally took Petra after fierce fighting, destroying its defenses.

In the same year, a Persian attack led by Mihr-Mihroe took over eastern Lazica. The truce from 545 was renewed outside Lazica for another five years. This was on condition that the Romans pay 2,000 pounds of gold each year. The Romans could not completely drive the Sasanians out of Lazica. In 554 AD, Mihr-Mihroe launched a new attack. He forced a newly arrived Byzantine army out of Telephis. In Lazica, the war continued without a clear winner for several years. Neither side could make any big gains.

Khosrau, who now had to deal with the White Huns, renewed the truce in 557. This time, it included Lazica. Talks continued for a final peace treaty. Finally, in 562, envoys from Justinian and Khosrau – Peter the Patrician and Izedh Gushnap – created the Fifty-Year Peace Treaty. The Persians agreed to leave Lazica. They received an annual payment of 30,000 nomismata (gold coins). Both sides agreed not to build new forts near the border. They also agreed to make diplomacy and trade easier.

War for the Caucasus (572–591 AD)

War broke out again shortly after Armenia and Iberia rebelled against Sasanian rule in 571 AD. This followed clashes between Roman and Persian allies in Yemen and the Syrian desert. It also happened after Roman talks for an alliance with the Western Turkic Khaganate against Persia. Justin II brought Armenia under his protection. Roman troops under Justin's cousin Marcian raided Arzanene. They invaded Persian Mesopotamia, where they defeated local forces.

Marcian's sudden dismissal and the arrival of troops under Khosrau led to Syria being attacked. The Roman siege of Nisibis failed, and Dara fell. For 45,000 gold coins, a one-year truce in Mesopotamia was arranged (later extended to five years). But in the Caucasus and on the desert borders, the war continued. In 575, Khosrau I tried to combine attacks in Armenia with talks for lasting peace. He invaded Anatolia and sacked Sebasteia. But he failed to take Theodosiopolis. After a fight near Melitene, his army suffered heavy losses while fleeing across the Euphrates under Roman attack. The Persian royal baggage was captured.

The Romans took advantage of Persian confusion. General Justinian invaded deep into Persian territory and raided Atropatene. Khosrau wanted peace. But he stopped these talks when Persian confidence returned. This happened after Tamkhusro won a victory in Armenia. Roman actions there had made local people angry. In the spring of 578, the war in Mesopotamia started again with Persian raids on Roman territory. The Roman general Maurice fought back by raiding Persian Mesopotamia. He captured the stronghold of Aphumon and sacked Singara. Khosrau again started peace talks. But he died early in 579. His successor Hormizd IV (ruled 578-590) chose to continue the war.

In 580, Hormizd IV ended the Caucasian Iberian monarchy. He turned Iberia into a Persian province ruled by a marzpan (governor). During the 580s, the war continued without a clear winner. Both sides had victories. In 582, Maurice won a battle at Constantia over Adarmahan and Tamkhusro, who was killed. But the Roman general did not follow up his victory. He had to rush to Constantinople to pursue his goals of becoming emperor. Another Roman victory at Solachon in 586 also failed to break the stalemate.

The Persians captured Martyropolis through betrayal in 589. But that year, the stalemate ended. The Persian general Bahram Chobin, who had been dismissed and shamed by Hormizd IV, started a rebellion. Hormizd was overthrown in a palace coup in 590. His son Khosrau II replaced him. But Bahram continued his revolt anyway. The defeated Khosrau was soon forced to flee to Roman territory for safety. Bahram took the throne as Bahram VI. With help from Maurice, Khosrau started a rebellion against Bahram. In 591, the combined forces of his supporters and the Romans defeated Bahram at the Battle of Blarathon. They restored Khosrau II to power. In exchange for their help, Khosrau not only returned Dara and Martyropolis. He also agreed to give the western half of Iberia and more than half of Persian Armenia to the Romans.

The Final Big War (602–628 AD)

In 602, the Roman army fighting in the Balkans rebelled. Their leader was Phocas. He managed to take the throne and then killed Maurice and his family. Khosrau II used the murder of his helper as an excuse for war. He wanted to take back the Roman province of Mesopotamia. In the early years of this war, the Persians had huge and unmatched success.

They were helped by Khosrau using a fake person who claimed to be Maurice's son. They were also helped by the revolt against Phocas led by the Roman general Narses. In 603, Khosrau defeated and killed the Roman general Germanus in Mesopotamia. He then attacked Dara. Even with Roman reinforcements from Europe, he won another victory in 604. Dara fell after a nine-month siege. Over the next few years, the Persians slowly took over the fortress cities of Mesopotamia, one after another. At the same time, they won many victories in Armenia and slowly took control of the Roman military bases in the Caucasus.

Phocas's harsh rule caused a leadership crisis. General Heraclius sent his nephew Nicetas to attack Egypt. This allowed his son Heraclius the younger to claim the throne in 610. Phocas, an unpopular ruler, was finally removed by Heraclius, who had sailed from Carthage. Around the same time, the Persians finished conquering Mesopotamia and the Caucasus. In 611, they took over Syria and entered Anatolia, occupying Caesarea.

Heraclius drove the Persians out of Anatolia in 612. He then launched a major counter-attack in Syria in 613. He was completely defeated outside Antioch by Shahrbaraz and Shahin. The Roman position fell apart. Over the next ten years, the Persians conquered Palestine, Egypt, Rhodes, and several other islands in the eastern Aegean. They also destroyed Anatolia. Meanwhile, the Avars and Slavs took advantage of the situation to take over the Balkans. This brought the Roman Empire to the edge of collapse.

During these years, Heraclius worked hard to rebuild his army. He cut non-military spending, made the currency worth less, and melted down Church valuables. He did this with the support of Patriarch Sergius. This helped him raise the money needed to continue the war. In 622, Heraclius left Constantinople. He left the city to Sergius and general Bonus as temporary rulers for his son. He gathered his forces in Asia Minor. After training them to boost their spirits, he launched a new counter-attack. This attack felt like a holy war.

In the Caucasus, he defeated an army led by a Persian-allied Arab chief. Then he won a victory over the Persians under Shahrbaraz. After a quiet period in 623, while he negotiated a truce with the Avars, Heraclius continued his campaigns in the East in 624. He routed an army led by Khosrau at Ganzak in Atropatene. In 625, he defeated the generals Shahrbaraz, Shahin, and Shahraplakan in Armenia. In a surprise attack that winter, he stormed Shahrbaraz's headquarters and attacked his troops in their winter camps.

A Persian army commanded by Shahrbaraz, along with the Avars and Slavs, unsuccessfully attacked Constantinople in 626. Meanwhile, a second Persian army under Shahin suffered another crushing defeat from Heraclius's brother Theodore.

Meanwhile, Heraclius made an alliance with the Western Turkic Khaganate. They took advantage of the Persians' weakening strength to attack their lands in the Caucasus. Late in 627, Heraclius launched a winter attack into Mesopotamia. There, even though the Turkish soldiers who were with him left, he defeated the Persians at the Battle of Nineveh. Continuing south along the Tigris, he sacked Khosrau's great palace at Dastagird. He was only stopped from attacking Ctesiphon because the bridges on the Nahrawan Canal were destroyed. Khosrau was overthrown and killed in a coup led by his son Kavadh II. Kavadh II immediately asked for peace. He agreed to leave all occupied territories. Heraclius brought back the True Cross to Jerusalem in a grand ceremony in 629.

What Happened After the Wars

The terrible impact of this last war, combined with a century of almost constant fighting, left both empires very weak. When Kavadh II died only months after becoming king, Persia fell into years of family struggles and civil war. The Sasanians were further weakened by a struggling economy. They also faced heavy taxes from Khosrau II's wars, religious unrest, and the growing power of local landowners.

The Byzantine Empire was also badly affected. Its money reserves were used up by the war. The Balkans were now mostly controlled by the Slavs. Also, Anatolia was destroyed by repeated Persian invasions. The Empire's control over its recently regained lands in the Caucasus, Syria, Mesopotamia, Palestine, and Egypt was weak after many years of Persian rule.

Neither empire had a chance to recover. Within a few years, they were hit by the attacks of the Arabs. These Arabs were newly united by Islam. This attack was like a "human tsunami." The Sasanian Empire quickly fell to these attacks and was completely conquered. During the Byzantine–Arab wars, the tired Roman Empire lost its recently regained eastern and southern provinces. These included Syria, Armenia, Egypt, and North Africa. This reduced the Empire to a small area. It now only had Anatolia and a few islands and small areas in the Balkans and Italy. These remaining lands became very poor from frequent attacks. This marked a change from a classical city-based civilization to a more rural, medieval society.

However, unlike Persia, the Roman Empire survived the Arab attack. It held onto its remaining lands. It also successfully pushed back two Arab sieges of its capital in 674–678 and 717–718. The Roman Empire also lost its lands in Crete and southern Italy to the Arabs in later conflicts. But these lands were eventually taken back.

Fighting Styles and Strategies

When the Roman and Parthian Empires first met in the 1st century BC, it seemed like Parthia could push its border all the way to the Aegean and the Mediterranean Sea. However, the Romans pushed back the big invasion of Syria and Anatolia by Pacorus and Labienus. They were slowly able to use the weaknesses of the Parthian military system. This system was good for defending their own country but not for conquering new lands.

The Romans, on the other hand, kept changing and improving their "grand strategy" from Trajan's time onwards. By the time of Pacorus, they could attack the Parthians. Like the Sasanians in the late 200s and 300s, the Parthians generally avoided a long defense of Mesopotamia against the Romans. However, the Iranian plateau was never fully conquered. Roman expeditions always ran out of steam by the time they reached lower Mesopotamia. Their long supply lines through lands that were not fully peaceful left them open to revolts and counterattacks.

From the 300s AD onwards, the Sasanians grew stronger and became the attackers. They believed that much of the land added to the Roman Empire in Parthian and early Sasanian times rightfully belonged to Persia. Experts say that the Sasanians were more centrally organized than the Parthians. They formally set up defenses for their territory, even though they didn't have a permanent army until Khosrau I. In general, the Romans saw the Sasanians as a more serious threat than the Parthians. The Sasanians saw the Roman Empire as their main enemy. Both the Byzantines and the Sasanians used proxy warfare. This meant they fought through allied Arab kingdoms in the south and nomadic groups in the north, instead of fighting directly.

Militarily, the Sasanians continued the Parthians' heavy reliance on cavalry (soldiers on horseback). This was a mix of horse-archers and cataphracts. Cataphracts were heavily armored cavalry provided by the wealthy class. They also added war elephants from the Indus Valley. However, their infantry (foot soldiers) were not as good as the Romans'. The combined forces of horse archers and heavy cavalry defeated Roman foot-soldiers several times. This included those led by Crassus in 53 BC, Mark Antony in 36 BC, and Valerian in 260 AD.

Parthian tactics slowly became the standard way of fighting in the Roman Empire. Units of cataphractarii and clibanarii (types of heavy cavalry) were added to the Roman army. As a result, heavily armored cavalry became more important in both the Roman and Persian armies after the 200s AD and until the end of the wars. The Roman army also slowly added horse-archers (Equites Sagittarii). By the 400s AD, they were no longer just hired soldiers. They were slightly better individually than the Persian ones, according to Procopius. However, the Persian horse-archer units as a whole always remained a challenge for the Romans. This suggests the Roman horse-archers were smaller in number. By the time of Khosrow I, the combined cavalrymen (aswaran) appeared. They were skilled in both archery and using a lance.

On the other hand, the Persians adopted war machines from the Romans. The Romans were very good at siege warfare (attacking fortified places). They had developed many different siege machines. The Parthians, however, were not good at sieges. Their cavalry armies were better suited for hit-and-run tactics. These tactics destroyed Antony's siege equipment in 36 BC.

The situation changed with the rise of the Sasanians. Rome now faced an enemy who was also good at siege warfare. The Sasanians mainly used mounds, rams, mines, and to a lesser extent, siege towers and artillery. They also used chemical weapons, such as in Dura-Europos (256) and Petra (550-551). Using complex twisting machines was rare. This was because traditional Persian skill in archery reduced the need for them. Elephants were used (for example, as moving towers) where the land was not good for machines. Recent studies comparing the Sasanians and Parthians confirm that Sasanian siegecraft, military engineering, and organization were better. They were also better at building defensive works.

By the beginning of Sasanian rule, there were several buffer states between the empires. These were slowly taken over by the main government. By the 600s, the last buffer state, the Arab Lakhmids, was added to the Sasanian Empire. Experts note that in the 200s AD, these client states were important in Roman–Sasanian relations. But both empires slowly replaced them with an organized defense system. This system was run by the central government. It was based on a line of fortifications (called the limes) and fortified border cities, like Dara.

Towards the end of the 1st century AD, Rome organized the protection of its eastern borders through the limes system. This lasted until the Muslim conquests of the 600s, after improvements by Diocletian. Like the Romans, the Sasanians built defensive walls opposite their enemies' territory. According to R. N. Frye, it was under Shapur II that the Persian system was expanded. This was probably copied from Diocletian's building of the limes on the Syrian and Mesopotamian borders of the Roman Empire. The Roman and Persian border units were known as limitanei and marzobans, respectively.

The Sasanians, and to a lesser extent the Parthians, often moved large groups of people to new cities as a policy. This included not just prisoners of war (like those from the Battle of Edessa), but also the people from cities they captured. For example, the people of Antioch were moved to Weh Antiok Khosrow. These forced movements also helped spread Christianity in Persia.

The Persians seemed unwilling to fight at sea. There was some small Sasanian naval action in 620–23. The only major Byzantine navy action was during the Siege of Constantinople (626).

Why These Wars Mattered

The Roman–Persian Wars have been called "pointless" and "too depressing and tedious to think about." The historian Cassius Dio wisely noted their "never-ending cycle of armed fights." He observed that "it is shown by the facts themselves that [Severus'] conquest has been a source of constant wars and great expense to us. For it yields very little and uses up vast sums; and now that we have reached out to peoples who are neighbor of the Medes and the Parthians rather than of ourselves, we are always, one might say, fighting the battles of those peoples."

In the long series of wars between the two powers, the border in upper Mesopotamia stayed mostly the same. Historians point out that the border's stability over centuries is remarkable. Even though Nisibis, Singara, Dara, and other cities in upper Mesopotamia changed hands sometimes, owning these border cities gave one empire a trade advantage over the other. As Frye states:

One has the impression that the blood spilled in the warfare between the two states brought as little real gain to one side or the other as the few meters of land gained at terrible cost in the trench warfare of the First World War.

| "How could it be a good thing to hand over one's dearest possessions to a stranger, a barbarian, the ruler of one's bitterest enemy, one whose good faith and sense of justice were untried, and, what is more, one who belonged to an alien and heathen faith?" |

| Agathias (Histories, 4.26.6, translated by Averil Cameron) about the Persians, a judgment typical of the Roman view. |

Both sides tried to explain their military goals. Sometimes they were attacking, sometimes they were reacting. According to the Letter of Tansar and the Muslim writer Al-Tha'alibi, Ardashir I's and Pacorus I's invasions of Roman lands were to get revenge for Alexander the Great's conquest of Persia. This was thought to be the reason for later Iranian problems. This idea matches the Roman emperors Caracalla, Alexander Severus, and Julian, who wanted to be like Alexander.

Roman sources show long-held biases against the Eastern powers' customs, religions, languages, and governments. John F. Haldon emphasizes that "even though the conflicts between Persia and East Rome were about controlling the eastern border, there was always a religious and ideological part to it." From the time of Constantine, Roman emperors saw themselves as protectors of Christians in Persia. This made people in Sasanian Iran very suspicious of Christians' loyalties. It often led to Roman–Persian tensions or even military fights (for example, in 421–422).

A key feature of the final phase of the conflict was the importance of the Cross. What started in 611–612 as a raid soon became a war of conquest. The Cross became a symbol of imperial victory and a strong religious element in Roman imperial messages. Heraclius himself called Khosrau an enemy of God. Writers from the 500s and 600s were very hostile towards Persia.

How We Know About These Wars

The information about Parthian history and their wars with Rome is scarce and spread out. The Parthians followed the Achaemenid tradition. They preferred to pass down history by word of mouth. This meant their history became unclear once they were defeated. So, the main sources from this time are Roman (Tacitus, Marius Maximus, and Justin) and Greek historians (Herodian, Cassius Dio, and Plutarch). The 13th book of the Sibylline Oracles tells about the effects of the Roman–Persian Wars in Syria. It covers the time from Gordian III's rule to Palmyra's control by Odaenathus. After Herodian's writings, there are no more continuous written records of Roman history until the early 300s. These later records are by Lactantius and Eusebius, both from a Christian viewpoint.

The main sources for the early Sasanian period are not from that time. The most important ones include the Greeks Agathias and Malalas, the Persian Muslims al-Tabari and Ferdowsi, the Armenian Agathangelos, and the Syriac Chronicles of Edessa and Arbela. Most of these writers relied on later Sasanian sources, especially Khwaday-Namag. The Augustan History is not from the time it describes and is not always reliable. But it is the main story source for Severus and Carus. The three-language (Middle Persian, Parthian, Greek) inscriptions of Shapur are original sources. However, these were rare attempts at written history. By the end of the 300s AD, the Sasanians even stopped carving rock reliefs and leaving short inscriptions.

For the period between 353 and 378, there is an eyewitness account of the main events on the eastern border. This is in the Res Gestae by Ammianus Marcellinus. For events from the 300s to the 500s, the works of Sozomenus, Zosimus, Priscus, and Zonaras are especially valuable. The single most important source for Justinian's Persian wars up to 553 is Procopius. His followers Agathias and Menander Protector also provide many important details. Theophylact Simocatta is the main source for Maurice's rule. Theophanes, Chronicon Paschale, and the poems of George of Pisidia are useful sources for the last Roman–Persian war. Besides Byzantine sources, two Armenian historians, Sebeos and Movses, help create a clear story of Heraclius's war. They are considered by Howard-Johnston as "the most important of existing non-Muslim sources."

Images for kids

-

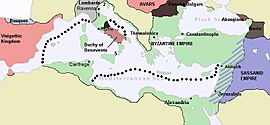

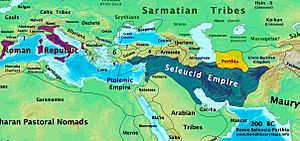

Rome, Parthia and Seleucid Empire in 200 BC. Soon both the Romans and the Parthians would invade the Seleucid-held territories, and become the strongest states in western Asia.

-

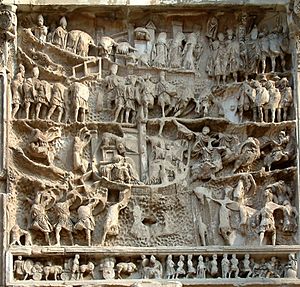

Reliefs depicting war with Parthia on the Arch of Septimius Severus, built to commemorate the Roman victories

-

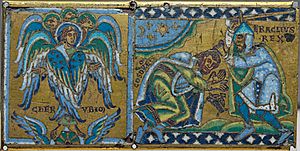

Bishapur Relief II commemorating Shapur I's victories on the Western front, depicting him on horseback with a captured Valerian, a dead Gordian III, and a kneeling emperor, either Philip the Arab or Uranius.

-

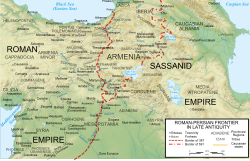

Julian's unsuccessful campaign in 363 resulted in the loss of the Roman territorial gains under the peace treaty of 299.

-

A rock-face relief at Naqsh-e Rostam, depicting the triumph of Shapur I over the Roman Emperor Valerian and Philip the Arab.

-

Relief of a Sasanian delegation in Byzantium, marble, 4th–5th century, Istanbul Archaeological Museums.

-

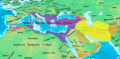

Roman and Sasanian Empires during Justinian's reign

-

Hunting scene showing king Khosrau I (7th century Sasanian art, Cabinet des Medailles, Paris).

-

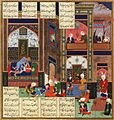

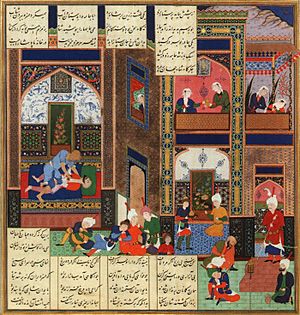

The assassination of Khosrau II, in a manuscript of the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp made by Abd al-Samad c. 1535. Persian poems are from Ferdowsi's Shahnameh.

-

Byzantine Empire (orange) by 650. By this point the Sasanian Empire had fallen to the Arab Muslim Caliphate as well as Byzantine Syria, Palestine and Egypt.

-

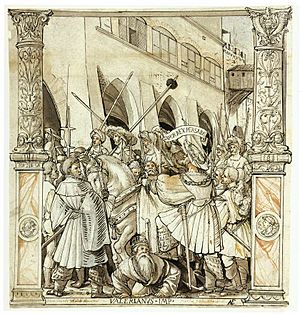

The Humiliation of Valerian by Shapur (Hans Holbein the Younger, 1521, pen and black ink on a chalk sketch, Kunstmuseum Basel)

See also

In Spanish: Guerras romano-sasánidas para niños

In Spanish: Guerras romano-sasánidas para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |