Valens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Valens |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

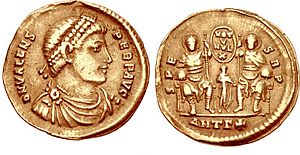

Solidus depicting Valens, marked:

d·n· valens p·f· aug· |

|||||

| Roman emperor in the East | |||||

| Reign | 28 March 364 – 9 August 378 | ||||

| Predecessor | Valentinian I (East and West) | ||||

| Successor | Theodosius I | ||||

| Western emperors | Valentinian I (364–375) Gratian (375–378) Valentinian II (375–378) |

||||

| Born | 328 Cibalae, Pannonia Secunda, Eastern Roman Empire |

||||

| Died | 9 August 378 (aged 49) Adrianople, Eastern Roman Empire |

||||

| Spouse | Domnica | ||||

| Issue | Anastasia Carosa Valentinianus Galates |

||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Valentinianic | ||||

| Father | Gratianus Funarius | ||||

| Religion | Semi-Arianism | ||||

Valens (Greek: Ουάλης, translit. Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was a Roman emperor from 364 to 378. His older brother, Valentinian I, made him co-emperor. Valens was given the eastern part of the Roman Empire to rule.

In 378, Valens was defeated and killed at the Battle of Adrianople. This battle was against the Goths, who were invading Roman lands. This event shocked people at the time and marked the start of barbarian groups moving into Roman territory.

As emperor, Valens faced many challenges from inside and outside the empire. He defeated a rebel named Procopius in 366. He also fought against the Goths across the Danube River in 367 and 369.

Later, Valens focused on the eastern border. Here, he faced the constant threat from Persia, especially in Armenia. He also had conflicts with the Saracens and Isaurians.

In Rome, he built the Aqueduct of Valens in Constantinople. This aqueduct was even longer than all the aqueducts in Rome. In 376–77, the Gothic War began. This happened after a plan to settle the Goths in the Balkans went wrong.

Valens came back from the east to fight the Goths himself. But he didn't work well with his nephew, Gratian, the western emperor. Poor battle plans led to Valens and much of his army dying near Adrianople in 378.

Some people described Valens as unsure, easily influenced, and not a great general. However, he was a careful and skilled administrator. One important thing he did was to greatly reduce taxes for the people. But he was also suspicious and worried about his safety. This led to many trials and punishments for people accused of treason. This damaged his reputation. In religious matters, Valens preferred a middle ground between different Christian groups. He didn't bother the pagans much.

Contents

Early Life & Military Career

Valens was born in 328 in Cibalae (Vinkovci). His brother, Valentinian, was born in 321. They came from an Illyrian family. Their father, Gratianus Funarius, was a high-ranking officer in the Roman army. He also served as a governor in Africa.

The brothers grew up on family lands in Africa and Britain. Both were Christians, but they followed different branches of Christianity. Valentinian was a Nicene Christian, and Valens was an Arian Christian.

As an adult, Valens served in the imperial guard. He worked under emperors Julian (361–363) and Jovian (363–364). A historian from the 5th century, Socrates Scholasticus, said Valens refused to offer pagan sacrifices. This was during the rule of Emperor Julian, who believed in many gods.

Valens's older brother, Valentinian, also joined the imperial guard. He became a high-ranking officer in 357. He served in Gaul and Mesopotamia during the reign of Constantius II (337–361). Valens's oldest nephew, Gratian, was born in 359. He was the son of Valentinian and his wife Marina Severa.

Emperor Julian died in battle against the Persians in June 363. His successor, Jovian, quickly headed to Constantinople to secure his power. But Jovian died unexpectedly in February 364. During his short rule, Jovian had given Valentinian an important military rank.

The historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that Valentinian was called to Nicaea. A group of military and civil leaders declared him emperor. This happened on February 25, 364.

Becoming Emperor

Valentinian made his brother Valens a military commander on March 1, 364. Both brothers became Roman consuls for the first time. People generally thought Valentinian needed help to manage the huge Roman Empire.

So, on March 28 of the same year, soldiers demanded a second emperor. Valentinian chose his brother Valens as co-emperor. This happened at the Hebdomon, outside the Constantinian Walls.

Early Years as Emperor

Both emperors were briefly sick, which delayed them in Constantinople. Once they recovered, they traveled together. They went through Adrianople and Naissus to Mediana. There, they divided the Roman Empire.

Valens received the eastern half of the Empire. This included Greece, the Balkans, Egypt, Anatolia, and the Levant. This land stretched to the border with the Sasanian Empire. Valentinian took the western half. He needed to deal with wars against the Alemanni there right away.

The brothers began their consulships in their capitals. Valens was in Constantinople, and Valentinian was in Mediolanum (Milan). Valens's wife, Domnica, may have become empress in 364.

In the summer of 365, a large 365 Crete earthquake and tsunami hit the Eastern Mediterranean. This caused much destruction.

The empire had recently lost control of most of its lands in Mesopotamia and Armenia. This was due to a treaty Jovian made with Shapur II of the Sasanian Empire. Valens's first goal after the winter of 365 was to move east. He hoped to improve the situation there.

Procopius's Rebellion (365–366)

While Valens was away from the capital, Procopius declared himself emperor. This happened on September 28, 365. Procopius was a relative of the previous emperor, Julian. He had served under earlier emperors. Some believed he might have been Julian's chosen successor.

Procopius gained control of the provinces of Asia and Bithynia. He got more and more support for his rebellion. Valens sent an army to Constantinople. But the soldiers joined Procopius. He used his connection to the respected Constantinian Dynasty to gain support. He was always seen with Constantia, the daughter of Constantius II, and her mother, Faustina.

Valens sent more troops under experienced generals. After eight months, Valens's forces won. They defeated Procopius in battles at Thyatira and Nacoleia. Procopius was betrayed by his own guards and executed on May 27, 366. Valens could then focus on outside enemies, the Sasanian Empire and the Goths.

The Valentinianic Family

Valens's son, Valentinianus Galates, was born on January 18, 366. In the same year, Valens's nephew Gratian was made a consul. He was also given the title nobilissimus puer.

In 367, Valentinian became very ill. This encouraged him to name a successor. He chose the eight-year-old Gratian as his co-emperor on August 24. In 368, Valentinian and Valens were consuls for the second time.

Money Changes

Between 365 and 368, Valentinian and Valens changed the Roman money system. They ordered that all precious metal be melted down in the main imperial treasury before making coins. These coins were marked with "ob" for gold and "ps" for silver. Valentinian also improved tax collection and spent money carefully.

First Gothic War: 367–369

During Procopius's rebellion, the Gothic king Ermanaric had promised to send troops to help Procopius. The Gothic army, said to be 30,000 men, arrived too late. But they still invaded Thrace and started stealing from farms. Valens, after defeating Procopius, surrounded them and forced them to surrender.

Ermanaric protested. Valens refused to make up for his actions, so war was declared. In spring 367, Valens crossed the Danube River. He attacked the Visigoths led by Athanaric. The Goths fled into the Carpathian Mountains. The campaign ended without a clear winner.

The next spring, a Danube flood stopped Valens from crossing. Instead, the Emperor had his troops build forts. In 369, Valens crossed the river again. He devastated the land, forcing Athanaric to fight. Valens won and took the title Gothicus Maximus. This was just in time for his five-year celebration as emperor. Athanaric and his forces were able to retreat and asked for peace.

Luckily for the Goths, Valens expected a new war with the Sasanid Empire in the Middle East. So, he was willing to make peace. In early 370, Valens and Athanaric met in the middle of the Danube. They agreed to a treaty that ended the war. The treaty mostly stopped trade and troop exchanges between Goths and Romans.

Middle Years as Emperor: 369–373

In 369, Valentinianus Galates became consul for the first time. He was also called nobilissimus puer. Around 370, Galates died of an illness in Caesarea in Cappadocia (Kayseri).

Valentinian and Valens were consuls for the third time in 370. On April 9, 370, the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople was opened. This church was next to the Mausoleum of Constantine.

Valens's sister-in-law, Marina Severa, died in the same year. Valentinian then married Justina. In autumn 371, Valens's second nephew, also named Valentinian, was born to Justina. This might have happened in Augusta Treverorum (Trier).

Gratian, who was 15, married Constantius II's 13-year-old daughter, Constantia, in 374. This wedding took place in Trier. Both Constantia and Justina were related to the family of Constantine. These marriages connected the Valentinianic and Constantinian ruling families.

Valens celebrated his ten-year anniversary as emperor on March 29, 374. In 375, the Baths of Carosa were opened in Constantinople. They were named after Valens's daughter, Carosa.

Valens went east after defeating the Goths. He started preparing an attack on Persia, which was threatening Armenia, in 375. But Valens was sidetracked by wars against the Saracens and the Isaurians.

Persian War: 373

Valens made a quick peace with the Goths in 369 because things were getting worse in the East. In 363, Jovian had given up Rome's claim to control Armenia. Shapur II of the Sasanian Empire wanted to take advantage of this.

The Persian emperor started to win over Armenian lords. He eventually forced the Armenian king, Arshak II, to switch sides. Shapur quickly arrested and imprisoned Arshak. The Armenian nobles asked Valens to send back Arshak's son, Pap. Valens agreed and sent Pap back to Armenia. But Valens could not give him military support because he was fighting the Goths.

In response, Shapur led an invasion to take control of Armenia. Pap and his followers hid in the mountains. The Armenian capital, Artaxata, and other cities were destroyed. Shapur sent another army to Caucasian Iberia. This army drove out the pro-Roman king, Sauromaces II. Shapur put his own choice, Sauromaces's uncle Aspacures II, on the throne.

In the summer after his peace with the Goths, Valens sent his general Arinthaeus to help Pap. The next spring, a force of twelve legions was sent under Terentius. Their job was to get Iberia back and guard Armenia.

When Shapur attacked Armenia again in 371, Valens's generals defeated his forces. This happened at Bagavan and Gandzak. Valens had gone against the 363 treaty, but he successfully defended his actions. A truce was made after the 371 victory. This truce lasted for five years while Shapur dealt with an invasion on his eastern border.

Meanwhile, problems arose with the young king Pap. He was said to have had the Armenian patriarch Nerses killed. He also demanded control of several Roman cities, including Edessa. There was also a disagreement about choosing a new patriarch for Armenia. Pap chose someone without the usual approval from Caesarea.

Valens's generals pressured him. They feared Pap would join the Persians. So, Valens tried to capture Pap but failed. Later, he had Pap executed in Armenia. In his place, Valens put another king, Varazdat. Varazdat ruled with the help of the general Mushegh Mamikonian, who was a friend of Rome.

The Persians were not happy about any of this. They started pushing again for Rome to follow the 363 treaty. As the eastern border became tense in 375, Valens began to prepare for a big military trip.

However, other problems appeared. In Isauria, a mountainous area, a major revolt broke out in 375. This took away troops that were supposed to be in the East. Also, by 377, the Saracens under Queen Mavia rebelled. They destroyed a large area from Phoenicia to the Sinai. Valens successfully stopped both uprisings. But these conflicts closer to home limited his actions on the eastern border.

Later Years as Emperor: 373–376

Valens became the senior emperor when his older brother Valentinian died. Valentinian died on November 17, 375, while fighting the Quadi in Pannonia. He may have died from a stroke. His body was prepared and began its journey to Constantinople, arriving the next year.

Gratian was then the only emperor in the western empire. But some of Valentinian's generals supported his four-year-old second son, Valentinian II. The army declared Valentinian II emperor, even though Gratian was already in power. Valentinian's close advisors and his Arian Christian widow, Justina, still had a lot of influence. Valens and Valentinian II were consuls for the year 376. This was Valens's fifth time as consul.

The body of the late emperor Valentinian arrived in Constantinople on December 28, 376. But it was not yet buried.

Second Gothic War: 376–378

The Huns began to move, pushing the Goths out of their lands. The Goths then sought protection from the Romans. Valens allowed the Goths, led by Fritigern, to cross the Danube River. However, Roman officials treated the Gothic settlers badly. This led them to revolt in 377. They sought help from the Huns and the Alans, starting the Gothic War (376–382).

Valens was consul for the sixth time in 378, again with Valentinian II. Valens returned from the east to fight the Goths. Gratian fought a war with the Alamanni in early summer 378. Valens asked his nephew and co-emperor Gratian for help against the Goths in Thrace. Gratian started moving east. But Valens did not wait for the western armies to arrive before attacking.

Valens's plans for an eastern campaign never happened. In 374, some troops were moved to the Western Empire. This left gaps in Valens's mobile forces. To prepare for an eastern war, Valens started a big recruitment program to fill these gaps.

It was not entirely bad news when Valens heard of Ermanaric's death. His kingdom broke apart because of an invasion by large groups of Huns from the far east. The Goths could not hold the Dniester or the Prut rivers against the Huns. So, they moved south in a huge migration. They looked for new homes and safety south of the Danube, in Roman lands. They might have thought they could defend these lands against the enemy.

In 376, the Visigoths under their leader Fritigern reached the lower Danube. They sent an ambassador to Valens, who had set up his capital in Antioch. They asked for a safe place to live.

Valens's advisors quickly pointed out that these Goths could provide troops. This would increase Valens's army and reduce his need to recruit from the provinces. This would also increase tax money. However, it would mean hiring them and paying them in gold or silver. Fritigern had been in contact with Valens in the 370s. Valens had supported him in a fight against Athanaric, who was persecuting Gothic Christians.

Many Gothic groups asked to enter the empire. But Valens only allowed Fritigern and his followers. However, others soon followed. When Fritigern and his Goths crossed the Danube, Valens's mobile forces were busy in the east. They were on the Persian border. This meant that only local defense units were there to oversee the Goths' settlement.

The small number of Roman troops could not stop other groups from crossing the Danube. These included Ostrogoths, and later Huns and Alans. What started as a controlled resettlement could turn into a major invasion.

The situation got worse because of corruption in the Roman government. Valens's generals took bribes instead of taking weapons from the Goths, as Valens had ordered. Then, they angered the Goths by charging very high prices for food. This drove the Goths to desperation. Meanwhile, the Romans failed to stop other barbarian groups from crossing who were not part of the treaty.

In early 377, the Goths revolted after a fight with the people of Marcianopolis. They defeated the corrupt Roman governor Lupicinus near the city at the Battle of Marcianople.

After joining forces with the Ostrogoths, the combined barbarian group spread out. They destroyed the countryside before meeting Roman forces. In a bloody battle at Ad Salices, the Goths were stopped for a moment. Saturninus, Valens's commander, tried to trap them between the lower Danube and the Euxine Sea. He hoped to starve them into surrendering.

However, Fritigern forced him to retreat. He invited some of the Huns to cross the river behind Saturninus's defenses. The Romans then fell back, unable to stop the invasion. But an elite force of his best soldiers, led by General Sebastian, was able to attack and destroy several smaller raiding groups.

By 378, Valens himself was ready to march west from his eastern base in Antioch. He took almost all his troops from the east, leaving only a small force. Some of these were Goths. He moved west, reaching Constantinople by May 30, 378.

Valens's advisors and generals told him to wait for Gratian and his troops. Gratian's army was coming from Roman Gaul, fresh from defeating the Alemanni. Gratian himself strongly urged this careful approach in his letters. But the people of Constantinople were demanding that the emperor march against the enemy. They were comparing him unfavorably to his co-emperor. Valens decided to advance at once and win a victory on his own.

Battle of Adrianople

On August 9, 378, Valens and most of his army were killed. This happened while fighting the Goths at the Battle of Adrianople. The battle was near Hadrianopolis in Thrace (Edirne).

After a short stay to build up his army, Valens moved to Adrianople. From there, he marched against the combined barbarian army on August 9, 378. This battle became known as the Battle of Adrianople.

Negotiations were tried, but they broke down. A Roman unit attacked, pulling both sides into battle. The Romans held their own at first. But they were crushed when Visigoth cavalry arrived by surprise and split their lines.

The main source for the battle is Ammianus Marcellinus. Valens had left a large guard with his supplies and treasures. This made his fighting force smaller. His right cavalry wing arrived at the Gothic camp before the left wing. It was a very hot day, and the Roman cavalry fought without proper support. They wasted their efforts while suffering in the heat.

Meanwhile, Fritigern again sent a peace messenger. This delay meant that the Romans on the field began to suffer from the heat. The army's strength was further reduced when a Roman archer attack happened at the wrong time. This made it necessary to call back Valens's messenger. The archers were defeated and retreated.

Gothic cavalry, returning from gathering food, now attacked. This was probably the most important event of the battle. The Roman cavalry fled.

Ammianus gives two accounts of Valens's death. In the first, Ammianus says Valens was "mortally wounded by an arrow, and presently breathed his last breath." His body was never found or properly buried. In the second account, Ammianus says the Roman infantry was left alone, surrounded, and cut to pieces. Valens was wounded and carried to a small wooden hut. The Goths surrounded the hut and set it on fire. They apparently didn't know the emperor was inside. According to Ammianus, this is how Valens died.

A third, less certain, story says Valens was hit in the face by a Gothic dart. He then died while leading a charge. He wore no helmet to encourage his men. This action supposedly turned the battle, leading to a tactical win but a strategic loss.

The church historian Socrates also gives two accounts for Valens's death.

When the battle was over, two-thirds of the eastern army was dead. Many of their best officers had also died. What was left of Valens's army was led away under the cover of night.

J. B. Bury, a famous historian, said the battle was "a disaster and disgrace that need not have occurred."

For Rome, the battle crippled the government. Emperor Gratian, who was nineteen, was overwhelmed. He was unable to handle the disaster until he appointed Theodosius I. The total defeat meant the government lost important precious metal resources. This was because all the gold and silver had been kept with the imperial court. Valens was declared a god after his death.

Valens's Legacy

Historian A. H. M. Jones wrote that Valens was "utterly undistinguished." He was only a guard before becoming emperor and had no military skill. Jones added that Valens showed his insecurity by being suspicious of plots. He severely punished those he thought were traitors.

However, Jones also admitted that Valens was a careful administrator. He cared about the common people. Like his brother, he was a serious Christian. He reduced the heavy taxes that had been put in place by Constantine and his sons. He respected his brother's reform laws. His moderation and purity in his private life were praised.

At the same time, his reign was marked by continuous punishments and executions. These came from his weak and fearful nature. Historian Gibbon wrote, "An anxious regard to his personal safety was the ruling principle of the administration of Valens." Dying in such a terrible battle is seen as the low point of his unlucky career. This is especially true because of the huge impact of Valens's defeat.

Adrianople marked the beginning of the end for Roman control over its lands in the late Empire. People at the time realized this. Ammianus understood it was the worst defeat in Roman history since the Battle of Edessa. Another historian, Rufinus, called it "the beginning of evils for the Roman empire then and thereafter."

Valens is also known for ordering a short history of the Roman State. This work was written by Valens's secretary, Eutropius. It is called Breviarium ab Urbe condita. It tells the story of Rome from its founding. Some historians believe Valens wanted to learn Roman history. This would help him, his family, and his appointees fit in better with the Roman Senate.

Religious Policy

During his time as emperor, Valens had to deal with different Christian beliefs. These differences were starting to cause divisions in the Empire. Julian (361–363) had tried to bring back the pagan religions. He used the disagreements among Christian groups to his advantage. Many soldiers were pagan. However, his actions were often seen as too extreme. Before he died in a war against the Persians, people often looked down on him. His death was seen as a sign from the Christian God.

Valens was baptized by the Arian bishop of Constantinople. This happened before his first war against the Goths. Christian writers who supported the Nicene view said Valens was part of the Arian group. They accused him of persecuting Nicene Christians. However, modern historians say both Valens and Valentinian I cared most about keeping social order. They say their religious concerns were less important.

Although Athanasius had to hide briefly during Valens's rule, Valens relied closely on his brother Valentinian. He treated St. Basil kindly. Both Athanasius and St. Basil supported the Nicene position. Not long after Valens died, Arianism in the Roman East came to an end. His successor, Theodosius I, made Nicene Christianity the official state religion of Rome. He then suppressed the Arians.

See also

In Spanish: Valente para niños

In Spanish: Valente para niños

- Aphrahat (hermit)