Valentinian II facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Valentinian II |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

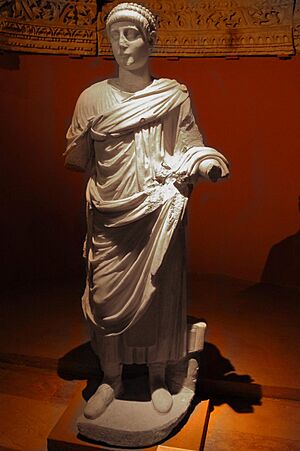

Marble statue found in Aphrodisias, usually identified as Valentinian II

|

|||||

| Roman emperor (in the West) | |||||

| Reign | 22 November 375 – 15 May 392 (senior from 28 August 388) | ||||

| Predecessor | Valentinian I | ||||

| Successor | Eugenius and Theodosius I | ||||

| Co-rulers |

|

||||

| Born | 371 Treveri, Gallia Belgica, Western Roman Empire |

||||

| Died | 15 May 392 (aged 21) Vienne, Viennensis, Western Roman Empire |

||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Valentinian | ||||

| Father | Valentinian I | ||||

| Mother | Justina | ||||

| Religion | Arian Christianity | ||||

Valentinian II (Latin: Valentinianus; 371 – 15 May 392) was a Roman emperor who ruled the western part of the Roman Empire from 375 to 392 AD. He started as a junior co-ruler with his older half-brother. Later, he was pushed aside by another ruler, but eventually became the main emperor after 388. However, he had limited real power.

Valentinian II was the son of Emperor Valentinian I and Empress Justina. When his father died, military leaders made him emperor at just four years old. Until 383, Valentinian II shared power in the West with his half-brother Gratian. Meanwhile, his uncle Valens ruled the East until 378, followed by Theodosius I from 379.

In 383, a general named Magnus Maximus took over and killed Gratian. Valentinian's court in Milan then became important. In 387, Maximus invaded Italy, forcing Valentinian and his family to flee to Thessalonica. There, they got help from Theodosius. Theodosius defeated Maximus and put Valentinian back in charge in the West. However, Valentinian was under the watchful eye of a powerful general named Arbogast. In 392, after many disagreements with Arbogast, Valentinian was found dead in his room. The exact reasons for his death are still unknown.

Contents

Becoming Emperor: Valentinian's Early Life (371–375)

Valentinianus was born to Emperor Valentinian I and his second wife, Justina. He was the half-brother of Valentinian's other son, Gratian, who had already been sharing the imperial title with their father since 367. Valentinian II also had three sisters: Galla, Grata, and Justa.

In 375, the elder Emperor Valentinian I died during a military campaign. Neither Gratian, who was in Trier, nor his uncle Valens, the emperor of the East, were asked for their opinion by the army commanders. Instead, the leading generals and officials, including Merobaudes and Valentinian II's uncle Cerealis, declared the four-year-old Valentinian as augustus (emperor). This happened on November 22, 375, in Aquincum.

The army, especially its Frankish general Merobaudes, might have been worried that Gratian was not very good at military leadership. To prevent the army from splitting, they chose a young boy who would not immediately try to take military command. They also wanted to stop other successful generals from becoming emperors or gaining too much power. For example, two powerful generals, Sebastianus and Count Theodosius, were removed or executed within a year of Valentinian becoming emperor.

Ruling from Milan (375–387)

Gratian had to accept the generals who supported his young half-brother. It is said that Gratian enjoyed teaching Valentinian. According to the historian Zosimus, Gratian ruled the provinces beyond the Alps, like Gaul, Hispania, and Britain. Meanwhile, Italy, parts of Illyricum, and North Africa were supposedly under Valentinian's rule.

However, Gratian and his court were mostly in charge of the entire Western Empire. Valentinian did not create any laws and was not often mentioned in official writings. In 378, their uncle, Emperor Valens, died in a battle against the Goths. Gratian then invited the general Theodosius to become emperor in the East.

As a child, Valentinian II was influenced by his mother, Empress Justina, and others at the court in Milan. They followed a Christian belief called Arianism. This was different from the beliefs of the Nicene bishop of Milan, Ambrose, who often disagreed with them.

In 383, Magnus Maximus, a commander of the armies in Britain, declared himself Emperor. He took control of Gaul and Hispania. Gratian was killed while trying to escape from him. Before this, Valentinian and his court in Milan had little power. But Gratian's death suddenly made them very important. For a while, Valentinian's court, with help from Bishop Ambrose, made a deal with Maximus. Theodosius even recognized Maximus as a co-emperor in the West.

Valentinian tried to stop the destruction of pagan temples in Rome. Encouraged by this, pagan senators, led by Aurelius Symmachus, asked in 384 for the Altar of Victory to be put back in the Senate House. Gratian had removed this altar in 382. Valentinian refused their request, showing he did not support the old pagan traditions of Rome. Bishop Ambrose also opposed putting the altar back, though he said he wasn't the one who decided to remove it in the first place.

In 385, Bishop Ambrose refused an imperial request to give up a church for Easter celebrations by the Imperial court. This angered Justina, Valentinian, and other high-ranking officials who followed Arianism. Ambrose wrote that Justina used her influence over her young son to oppose him. However, not only Justina but also the wider imperial court opposed Ambrose. When Ambrose was called to be punished, the people who supported him rioted. Gothic soldiers were stopped by Ambrose himself from entering the church.

Some accounts say that Justina convinced Valentinian to banish Ambrose, but Ambrose barricaded himself inside the church with the support of the people. Imperial troops surrounded him, but Ambrose held strong. He even claimed to have found the bodies of two ancient martyrs under the church, which encouraged his followers. Later, Magnus Maximus reportedly used the emperor's religious differences against him, writing a letter criticizing Valentinian.

Between 386 and 387, Maximus crossed the Alps and threatened Milan. Valentinian II and Justina fled to Theodosius in Thessalonica. Theodosius agreed to help, and his marriage to Valentinian's sister Galla sealed the deal. In 388, Theodosius marched west and defeated Maximus.

Ruling from Vienne (388–392)

After Maximus was defeated, Valentinian did not take part in Theodosius's victory celebrations. Valentinian and his court were moved to Vienne in Gaul. His mother, Justina, had already passed away. Vienne was far from Bishop Ambrose's influence. One speaker, Pacatus, praised Theodosius, saying the empire belonged to his two sons, Arcadius and Honorius, and barely mentioned Valentinian. Theodosius stayed in Milan until 391, putting his own supporters in important positions in the West. On coins from the East, Valentinian was still shown as a junior co-ruler, like Arcadius. Many modern historians believe Theodosius did not intend for Valentinian to truly rule, as he planned for his own sons to take over.

When Theodosius decided to return to the East, he appointed his trusted general, Arbogast, to lead the armies in the Western provinces (except Africa) and to be Valentinian's guardian. Arbogast acted in Valentinian's name but was only truly answerable to Theodosius. While Arbogast successfully fought battles along the Rhine River, the young emperor stayed confined in Vienne. This was very different from his father and older brother, who had led armies at his age.

Arbogast had so much control over the emperor that, in one story, he even killed Harmonius, a friend of Valentinian, right in front of the emperor. Valentinian wrote to Theodosius and Ambrose, complaining about how Arbogast controlled him. He also rejected his earlier Arian beliefs and invited Ambrose to Vienne to baptize him.

The situation became very tense when Arbogast stopped the emperor from leading the Gallic armies into Italy to fight a barbarian threat. In response, Valentinian officially fired Arbogast. But Arbogast ignored the order, publicly tearing it up. He argued that Valentinian had not appointed him in the first place. This showed everyone who truly held the power.

Valentinian's Death

On May 15, 392, Valentinian was found dead in his home in Vienne.

His body was brought to Milan for burial by Bishop Ambrose. His sisters, Justa and Grata, mourned him. He was buried in a porphyry sarcophagus next to his brother Gratian, likely in the Chapel of Sant'Aquilino, which was part of San Lorenzo. He was honored as a god after his death, with the title consecratio: Divae Memoriae Valentinianus, lit. 'Valentinian of Divine Memory'.

At first, Arbogast recognized Theodosius's son Arcadius as the new emperor in the West, seeming surprised by Valentinian's death. After three months, with no communication from Theodosius, Arbogast chose an official named Eugenius to be emperor. Theodosius initially allowed this, but in January 393, he made his eight-year-old son Honorius augustus to replace Valentinian II. A civil war followed, and in 394, Theodosius defeated Eugenius and Arbogast at the Battle of the Frigidus.

Why Valentinian II's Reign Was Important

Valentinian himself seemed to have no real power. He was mostly a figurehead, meaning he was a leader in name only, controlled by powerful people around him. These included his mother, his co-emperors, and strong generals.

Since the Crisis of the Third Century, the Roman Empire had often been ruled by powerful generals. This system changed many times. Constantine I and his sons, who were strong military leaders, brought back the idea of emperors passing power down to their children. Valentinian I continued this tradition.

The problem with these two ideas—powerful generals versus family succession—became clear during Valentinian II's reign. He was just a child. His time as emperor showed what was to come in the fifth century. During that time, many emperors were children or weak rulers who were controlled by powerful generals and officials in both the West and the East.

See also

In Spanish: Valentiniano II para niños

In Spanish: Valentiniano II para niños

- Illyrian emperors