Byzantine Empire facts for kids

| 330–1453 | |

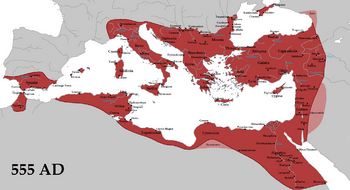

The empire in 555 under Justinian I, its greatest extent since the fall of the Western Roman Empire, with vassals in pink

|

|

| Capital | Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) |

|---|---|

| Common languages |

|

| Religion | Christianity (official) |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Autocracy |

| Notable emperors | |

|

• 306–337

|

Constantine I |

|

• 379–395

|

Theodosius I |

|

• 408–450

|

Theodosius II |

| Historical era | Late antiquity to Late Middle Ages |

Quick facts for kids Population |

|

|

• 457

|

16,000,000 |

|

• 565

|

26,000,000 |

|

• 775

|

7,000,000 |

|

• 1025

|

12,000,000 |

|

• 1320

|

2,000,000 |

| Currency | Solidus, denarius, and hyperpyron |

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was a powerful civilization that lasted for over 1,000 years. It was the eastern part of the old Roman Empire and had its capital city in Constantinople (which is now Istanbul, Turkey). While the western part of the Roman Empire fell apart in the 5th century AD, the Byzantine Empire kept going strong. It finally came to an end in 1453 when the Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople.

Contents

Exploring the Byzantine Empire's History

Historians don't all agree on exactly when the Byzantine Empire began. Some say it started around 300 AD, while others think it was closer to 500 AD. It's tricky because the Roman Empire slowly changed into the Byzantine Empire over many years.

Early Days of the Empire (Before 518 AD)

The Roman Empire was huge, and by the 3rd century AD, it was too big for one ruler. So, Emperor Diocletian (who ruled from 284 to 305 AD) decided to split it into eastern and western halves. He created a "Tetrarchy," meaning "rule of four," with two emperors in the East and two in the West. This system didn't last long, but the idea of a divided empire did.

Constantine I (306–337 AD) became the sole ruler in 324 AD. He built a new capital city called Constantinople on the site of an old town called Byzantium. This new capital was in a better location for defending the empire. Constantine also made big changes to the army and government. He introduced a stable gold coin called the solidus. He also supported Christianity, which became very important in the empire.

After Constantine, the empire faced many wars. Emperor Theodosius I (379–395 AD) brought stability back to the East. He allowed the Goths to settle in Roman lands. He also made Christianity the official religion of the empire. He was the last emperor to rule both the East and West. After his death, the Western Roman Empire became unstable and eventually fell.

The Eastern Empire, however, managed to survive. It avoided the problems that led to the West's downfall, like rebellious barbarian groups. Emperor Anastasius I (491–518 AD) was a skilled ruler. He made important financial changes that helped the empire. He was the first emperor in a long time to leave the empire in a peaceful state.

A Golden Age and Tough Times (518–717 AD)

The reign of Justinian I (527–565 AD) was a very important time for the Byzantine Empire. He had the Roman laws rewritten into a famous collection called the Corpus Juris Civilis. This law code influenced many future legal systems. Justinian also rebuilt much of Constantinople, including the amazing Hagia Sophia church.

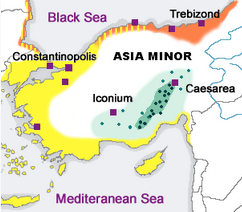

Justinian wanted to get back the lost western territories of the Roman Empire. His general, Belisarius, successfully conquered the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa in 534 AD. He then invaded Italy and defeated the Ostrogothic Kingdom.

However, Justinian's reign also had challenges. A terrible plague swept through the empire, killing many people and weakening the economy. The empire also faced wars with the Persians. Justinian left the empire strong but also under a lot of stress.

After Justinian, the empire faced more wars and lost some land. The Lombards took over much of northern Italy. The Avars and Slavs invaded the Balkans, causing trouble. Emperor Maurice (582–602 AD) fought hard to defend the empire, but his army rebelled and he was overthrown.

Bottom: the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, critically important during the 717–718 siege.

Then came Heraclius (610–641 AD). He fought a long and difficult war against the Persians and eventually defeated them. But soon after, a new threat appeared: the Arab armies. They quickly conquered many wealthy Byzantine provinces, including the Levant and Egypt. This greatly reduced the empire's size and income.

The next 75 years were difficult. Arab raids into Asia Minor were common. The Byzantines learned to defend their fortified cities and avoid big battles. Emperor Constans II (641–668 AD) started a new system called the "theme system." This divided the empire into military districts, with soldiers defending their own provinces.

With the help of a secret weapon called Greek fire, Constantine IV (668–685 AD) successfully defended Constantinople from an Arab siege in the 670s. However, the Byzantines also faced a new enemy, the Bulgars, who formed their own empire in the Balkans.

After a period of political chaos, Leo III became emperor in 717 AD. He successfully defended Constantinople from another major Arab siege in 717–718 AD. This was a huge victory and saved the empire.

Recovery and Expansion (718–867 AD)

Leo III and his son Constantine V (741–775 AD) were strong emperors. They fought off Arab attacks and brought stability back to the empire. Leo created a new law code called the Ecloga. Constantine V made peace with the new Abbasid Caliphate and fought successfully against the Bulgars.

However, these emperors also supported Byzantine Iconoclasm, which was against using religious icons. This caused a lot of disagreement within the empire and with the Roman Pope.

After a period of instability, Emperor Theophilos (829–842 AD) brought back some order. He used economic growth to build new structures, including strengthening the sea walls of Constantinople. His wife, Empress Theodora, ended the iconoclasm movement for good. The empire began to prosper again.

The Macedonian Dynasty's Golden Age (867–1081 AD)

The Macedonian dynasty began with Basil I (867–886 AD). His son, Leo VI (886–912 AD), was a very learned emperor. He collected and wrote many important books, including the Basilika, which was a Greek version of Justinian's law code. He also wrote a book about military tactics.

The empire saw many military successes under emperors like Nikephoros II (963–969 AD) and John I Tzimiskes (969–976 AD). They conquered new lands and defeated enemies like the Bulgarians and the Kievan Rus'.

The most famous emperor of this period was Basil II (976–1025 AD). He was a brilliant military leader. He spent decades fighting against Bulgaria and finally achieved a complete Byzantine victory in 1018. When he died, the empire stretched from the Danube River in the west to the Euphrates River in the east. It was a time of great power and influence.

After Basil II, the empire faced some challenges. There was political instability and financial problems. The empire also came under attack from new enemies: the Seljuk Turks in the east, the Pecheneg nomads in the north, and the Normans in the west.

In 1071, the Byzantines suffered two major defeats. The Normans captured Bari, their last city in Italy. And the Seljuk Turks won a decisive victory at the Battle of Manzikert, even taking the emperor Romanos IV Diogenes prisoner. These events led to a civil war and the loss of much of Anatolia to the Seljuks.

The Komnenian Restoration (1081–1204 AD)

Alexios I (1081–1118 AD) became emperor and began to restore the empire's power. He fought off the Normans and defeated the Pechenegs. He also asked the Pope for help against the Seljuks, which led to the First Crusade. This crusade helped the Byzantines regain some land in western Anatolia.

Alexios's son, John II (1118–1143 AD), and grandson, Manuel I (1143–1180 AD), continued to strengthen the empire. They fought many wars and used diplomacy to make alliances. Manuel I was especially good at building relationships with other rulers.

However, Manuel's death left the empire in a difficult position. There were problems within the imperial family and new enemies attacked the borders. Relations with Western Europe also got worse.

This led to a terrible event in 1204. The Fourth Crusade was supposed to go to Egypt, but instead, the crusaders attacked Constantinople. They sacked the city, stealing its wealth and causing huge damage. This was a major disaster for the Byzantine Empire.

The Final Centuries (1204–1453 AD)

After Constantinople was sacked, the Byzantine Empire broke into several smaller states. The most important were the Empire of Nicaea and the Despotate of Epirus. The Empire of Nicaea eventually managed to recapture Constantinople in 1261.

This brought a short period of revival under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos. But the empire was weak and surrounded by enemies. To fight the Latins, Michael had to take soldiers from Asia Minor and tax his people heavily. This caused a lot of unhappiness.

The empire continued to struggle. Civil wars weakened it further. The Ottoman Turks began to grow in power. They were often hired as mercenaries during Byzantine civil wars, which only helped them gain a foothold in Europe.

By the 1400s, Constantinople was a shadow of its former self. The city's population had shrunk dramatically. On April 2, 1453, Sultan Mehmed's huge Ottoman army laid siege to the city. Despite a brave defense by the much smaller Christian forces, Constantinople finally fell on May 29, 1453. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, was last seen fighting bravely in the streets. This marked the end of the Byzantine Empire.

How the Byzantine Empire Was Governed

The Emperor's Role

The emperor was the most powerful person in the Byzantine Empire. His power was immense and hard to fully describe. People in Constantinople and the patriarch (the head of the church) would officially approve his rule. The senate existed, but it mostly became a formal group that supported the emperor.

Many emperors were overthrown by force, but the empire was often ruled by families. There were nine dynasties between 610 and 1453. For most of that time, the empire was led by people related by blood or marriage. This was often because emperors would share power with their sons or relatives.

From the 7th century onwards, the empire was divided into military districts called themata. Each thema was led by a military commander called a strategos. This person was in charge of both the army and the local government. This system helped the empire defend itself during constant wars.

Byzantine Diplomacy and Foreign Relations

The Byzantine Empire was very skilled at diplomacy, which means dealing with other countries. This was one of its most important contributions to Europe. They were good at making treaties, forming alliances, and working with the enemies of their enemies. For example, they sometimes allied with the Turks against the Persians.

Byzantine diplomacy often involved sending long-term ambassadors. They also hosted foreign royals, sometimes as a way to keep them under control. They would impress visitors with amazing displays of wealth and power, making sure the word spread. Other tools included political marriages, giving out special titles, and even bribery. They also had a kind of early intelligence agency called the 'Bureau of Barbarians'.

After Emperor Theodosius I, the Byzantines focused on peace as a smart way to survive. Even when they had many resources, defending the empire was very expensive. They had many aggressive neighbors, so avoiding war was often the best plan.

Byzantine diplomacy helped new states that formed on former Roman lands. They drew these states into their influence, creating a network of relationships. They used Christianity as a tool to connect with other nations. However, their diplomacy with Muslim states was different, focusing mainly on war-related issues like hostages or preventing fights.

The main goal of Byzantine diplomacy was survival, not conquering new lands. This changed a bit from the 9th to 10th centuries, when they started to push back against Muslim power and bring Bulgarians under their control. Dealing with Western Europe became harder, especially during the Crusades. By the 11th century, the Byzantines started to treat other powerful states as equals.

Even when the empire was weak in its final centuries, its clever diplomacy helped it survive. They used their statecraft and the influence of the Constantinople patriarch to act like a great power.

Byzantine Law System

Roman law, which started with the Twelve Tables, became very confusing over time. There were many different sources and it wasn't clear what the law actually was. So, efforts were made to organize it.

Emperor Theodosius II (402–450 AD) created the Codex Theodosianus. This was a collection of laws issued since Constantine's time. Later, Emperor Justinian I (527–565 AD) ordered a complete standardization of Roman law. This massive work is known as the Corpus Juris Civilis. It included imperial decrees and the opinions of legal experts. This became the final authority on law.

The Corpus Juris Civilis was written in Latin, which became harder for people in the eastern provinces to understand. Also, Christianity became more connected to the law. Because of this, Emperor Leo III (717–741 AD) created a new law code called the Ecloga. It was written in Greek and was meant to be more humane.

Later, Emperor Leo VI (886–912 AD) completed a huge project to organize all Roman law into Greek. This work, called the Basilika, had 60 books and became the basis for all Byzantine law that followed.

The Byzantine Military

The Army's Evolution

In the 5th century, the Eastern Roman Empire had five armies, each with about 20,000 soldiers. These included border units (limitanei) and mobile forces (comitatenses). Historians say that in the 6th century, the empire could only really fight one major enemy at a time because of money issues.

The Arab conquests in the 7th century changed the army a lot. The old field forces became more like local militias with a core of professional soldiers. The government shifted the cost of supporting the armies onto local people. During Leo VI's reign (886–912 AD), these forces were tied into the tax system. Provinces became military regions called themata.

The Byzantine army was considered very strong. Some historians believe that during the Macedonian dynasty (867–1056 AD), the army was the best in the empire's history.

The military became more varied. It included local militia-like soldiers, professional thematic forces, and special imperial units based in Constantinople. Foreign soldiers, called mercenaries, were also used more and more. The famous Varangian Guard, made up of Norsemen and Russians, guarded the emperor.

Over time, the local thematic militias became less important. The government relied more on the imperial units, mercenaries, and allies. This led to a neglect of defense. Mercenary armies also caused political problems and civil wars, which weakened the empire's defenses. This resulted in the loss of important lands like Italy and Anatolia in the 11th century.

After 1081, the Komnenian emperors made big changes to the military and finances. They rebuilt a smaller, well-paid, and skilled army. However, these costs were hard to keep up. The system started to fall apart after Emperor Manuel I's reign (1143–1180 AD).

The Byzantine navy was very powerful. It controlled the eastern Mediterranean Sea and was active in the Black Sea and Aegean Sea. The navy was reorganized in the 7th century to fight against Arab naval power. Later, in the 11th century, the Byzantines lost their naval dominance to the Venetians and Genoans.

The navy's patrols, along with chains of watchtowers and fire signals, protected the empire's coast. Three naval themes (Cibirriote, Aegean Sea, Samos) and an imperial fleet were responsible for this. The imperial fleet included mercenaries like Norsemen and Russians, who later became the Varangians.

A new type of warship, the dromon, appeared in the 6th century. A version called the chelandia could even carry cavalry. These ships were powered by oars and designed for coastal travel. They were equipped with a special weapon called Greek fire in the 670s. This fiery liquid could even burn on water and was crucial in defending Constantinople.

Late Era Military (1204–1453 AD)

After recapturing Constantinople in 1261, the Palaiologos dynasty tried to rebuild the army. They used different types of soldiers, including volunteers, marines, and oarsmen. However, they couldn't afford to keep a large standing army. They relied mostly on mercenaries and a system where landowners provided a small force, mainly cavalry.

The navy was disbanded in 1284, and attempts to rebuild it were sabotaged by the Genoese. Frequent civil wars further weakened the empire. Emperors often hired Turkish mercenaries to fight these civil wars, which ironically helped the Ottomans gain more power. The Black Death also had a devastating impact on the population and the army.

Byzantine Society and Daily Life

Population Changes

At its largest in 540 AD, the empire's population might have been as high as 27 million people. But it dropped significantly to about 12 million by 800 AD due to plague and losing land to Arab invaders. It recovered to about 18 million by 1025 AD.

After Constantinople was recaptured in 1261, the population was around 3–5 million. By 1312, it had fallen to 2 million. When the Ottoman Turks captured Constantinople in 1453, only about 50,000 people lived in the city, which was a tenth of its peak population.

Education in the Empire

Education was not free and required money to attend. Most educated people were connected to the church. Primary schools taught reading, writing, and arithmetic. Secondary schools focused on subjects like grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. The Imperial University of Constantinople was founded in 425 AD and later restarted in 1046 as a center for law studies.

Becoming a Christian Empire

The Roman Empire was originally multi-lingual and had many different religions. But in 212 AD, all free men in the empire were granted citizenship. This led to more uniformity, especially in religious practices. Emperor Constantine's support for Christianity and the rise of Constantinople as the capital helped this change.

In the late 4th century, Emperor Theodosius I made laws restricting pagan activities. By 529 AD, Emperor Justinian I enforced conversions to Christianity. Pagan treasures were taken, funds were redirected, and legal discrimination led to the decline of paganism. This included the closing of philosophy schools and the end of the Ancient Olympics.

Slavery in Byzantium

In the 3rd century, about 10–15% of the population were enslaved. Over time, changes happened. Some jobs previously done by enslaved people became free market professions. The state also encouraged coloni, who were tenants tied to the land. They were a new legal category between free people and enslaved people.

From the 9th century onwards, emperors would free enslaved people from conquered lands. Christianity didn't directly end slavery, but by the 6th century, bishops had a duty to ransom Christians. There were also limits on trading Christians. However, slavery continued because there was a steady supply of non-Christians.

Economy and Daily Life

Agriculture was the main source of taxes. The government wanted everyone to stay on the land to keep up production. Most land was made up of small and medium-sized family farms around villages.

Marriage became a Christian institution in 741 AD, no longer just a private agreement. It was seen as a way to grow the population, pass on property, and support older family members. Women usually married between 15 and 20 years old. The average family had two children.

Women had good inheritance rights, even for all daughters. This might have prevented the rise of very large landholdings and powerful noble families that could challenge the state. Many women were widows (about 20%) and often managed family assets and businesses. Women were also major taxpayers and landowners.

Women's Roles

Even though women had the same social and economic status as men, they faced some legal limitations. They couldn't be soldiers or hold political office. They were mostly responsible for household duties. However, they also worked in many professions, like in the food and textile industries, as medical staff, in public baths, and in retail. Some women were even part of artisan guilds.

Languages Spoken

Right: The Joshua Roll, a 10th-century illuminated Greek manuscript possibly made in Constantinople (Vatican Library, Rome)

The Byzantine Empire never had one official language, but Latin and Greek were the main ones. In the early Roman Empire, knowing Greek was important for educated nobles. Latin was useful for a career in the military, government, or law. In the East, Greek became the most important language. It was also the language of the Christian Church and trade.

Many early emperors spoke both Latin and Greek. They often preferred Latin in public for political reasons. Many other languages were spoken throughout the empire, especially by the common people. These included Syriac, Coptic, Slavonic, Armenian, Georgian, and Celtic languages.

Byzantine Economy and Trade

After the Roman Empire split, the Western part became unstable. But the Byzantine Empire stayed strong, which helped its economy grow. A stable legal system and good infrastructure created a safe environment for business. In the 530s, the empire had about 30 million people and many natural resources, like gold mines and fertile fields in Egypt.

Many people lived in large cities inherited from the Roman Empire. Constantinople, the capital, was the biggest city in the world at the time, with at least 400,000 people. These cities continued to grow, showing the empire's wealth. Rural areas also developed, with more agricultural settlements.

Justinian I's efforts to reconquer North Africa and Italy were expensive. But they also reopened important trade routes in the Mediterranean Sea.

The Plague of Justinian caused a big drop in population, which hurt the economy. Wars with the Slavs, Avars, and Persians also made things worse. The Arab conquests in the 630s cut the empire's territory in half, including rich provinces like Egypt. These disasters led to a severe economic decline, with cities shrinking and trade reaching its lowest point by the 8th century.

However, reforms by the Isaurian emperors and later emperors helped the economy revive. From the 10th to the late 12th century, the Byzantine Empire was known for its luxury and wealth. Travelers were impressed by the riches in Constantinople.

The Fourth Crusade in 1204 severely damaged Byzantine manufacturing and trade. Western Europeans gained control of trade in the eastern Mediterranean. This was an economic disaster for the empire. The later Palaiologos emperors tried to revive the economy, but they struggled to control foreign and domestic trade. Constantinople lost its influence over trade rules, prices, and even the minting of coins.

The government tried to control interest rates and the activities of guilds (groups of skilled workers). During crises, the emperor and officials would ensure there was enough food for the capital and keep prices affordable. The government also collected taxes and used the money to pay officials or invest in public works.

Trade was a key part of the Byzantine economy, especially because the empire was surrounded by seas. Textiles, especially silk, were important exports. The state tightly controlled internal and international trade. It also had a monopoly on issuing coins, keeping a stable and flexible money system that helped trade.

Byzantine Arts and Culture

Architecture Styles

Byzantine architecture, especially for religious buildings, influenced many regions from Egypt to Russia. It is famous for its use of domes. The Byzantines invented pendentive architecture, which allowed them to place round domes on square rooms. Unlike Western European churches, Byzantine churches often had more centralized layouts, like the cross-in-square plan.

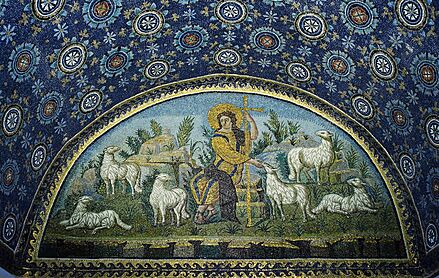

They often featured marble columns, decorated ceilings, and rich decorations, including many mosaics with golden backgrounds. Byzantine architects used stone and brick, and thin alabaster sheets for windows. Mosaics were used to cover brick walls. Famous mosaics can be seen in the Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki and the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna.

Byzantine Art

Emperor Constantine's support led to a burst of Christian art and architecture, including frescoes and mosaics. Christian images slowly replaced classical ones.

In the 720s, Emperor Leo III banned the use of pictures of Christ, saints, and biblical scenes. This was called Byzantine Iconoclasm. This ban lasted for over 100 years, and many religious artworks were destroyed. It wasn't until the 10th and early 11th centuries that Byzantine art fully recovered.

Most surviving Byzantine art is religious. It usually followed traditional styles that expressed church teachings. Painting in fresco, illuminated manuscripts, on wood panels, and mosaics were the main forms. Figurative sculpture was rare, except for small carved ivories.

Byzantine art was highly valued in Western Europe and greatly influenced medieval art. Its styles spread throughout the Orthodox world.

Science and Medicine in Byzantium

Byzantine science was important for passing on classical knowledge. It helped share ancient Greek ideas with the Islamic world and later with Renaissance Italy. Many important classical scholars held high positions in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The Byzantines carefully studied and preserved the writings of classical antiquity. So, Byzantine science was always connected to ancient philosophy. For example, Isidore of Miletus, who designed the Hagia Sophia, compiled the works of Archimedes around 530 AD. These works are known today thanks to Byzantine scholars.

John Philoponus, a philosopher from Alexandria, was the first to question Aristotelian physics. Unlike Aristotle, who used arguments, Philoponus used observations. His ideas later inspired Galileo Galilei to challenge Aristotle's physics centuries later.

The Byzantines were pioneers in creating hospitals. They were places that offered medical care and the chance for patients to get better, showing Christian charity.

Greek fire, a special weapon that could even burn on water, was invented by the Byzantines. It was very important in their victory over the Umayyad Caliphate during the siege of Constantinople (717–718 AD). Its invention is often credited to Callinicus of Heliopolis.

In the empire's final century, astronomy and other mathematical sciences were taught. Medicine was also a popular subject for scholars. When Constantinople fell in 1453, many Byzantine scholars fled to Italy. They brought with them ancient Greek knowledge of grammar, literature, mathematics, astronomy, botany, and medicine, which helped spark the Italian Renaissance.

Images for kids

-

A game of τάβλι (tabula) played by the Byzantine emperor Zeno in 480 and recorded by Agathias in c. 530 because of a very unlucky dice throw for Zeno (red), as he threw 2, 5 and 6 and was forced to leave eight pieces alone.

See also

In Spanish: Imperio bizantino para niños

In Spanish: Imperio bizantino para niños

- Family tree of Byzantine emperors

- Index of Byzantine Empire–related articles

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

- List of Byzantine revolts and civil wars

- List of Byzantine wars

- List of Roman dynasties

- Outline of the Byzantine Empire

- Succession of the Roman Empire

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |