First Crusade facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First Crusade |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crusades | |||||||||

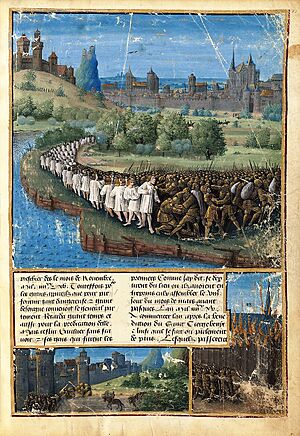

Miniature of Peter the Hermit leading the People's Crusade (Egerton 1500, Avignon, 14th-century) |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Crusader armies Army of Raymond of Saint-Gilles Army of Godfrey of Bouillon Army of Robert Curthose Army of Robert II of Flanders Army of Hugh the Great Armies of Bohemond of Taranto Armies of the People's Crusade Byzantine Empire |

Muslim States Seljuk Empire Emirate of Rum Danishmendids Fatimid Caliphate |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Crusader armies Raymond IV of Toulouse Adhemar of Le Puy # Godfrey of Bouillon Baldwin of Boulogne Hugh of Vermandois Stephen of Blois Robert II of Flanders Robert Curthose Peter the Hermit Bohemond of Taranto Tancred Byzantine Empire Alexios I Komnenos Tatikios Manuel Boutoumites |

Seljuks Kilij Arslan Yaghi-Siyan X Kerbogha Duqaq Ridwan Toghtekin Janah ad-Dawla Fatimids Iftikhar al-Dawla Al-Afdal Shahanshah |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Crusaders Estimated at 130,000 to 160,000 * 80,000 to 120,000 infantry * 17,000 to 30,000 knights |

Muslims Unknown |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Moderate or heavy (estimates vary) | Very heavy | ||||||||

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of several major religious wars, known as the Crusades. These wars were started and supported by the Latin Church during the Middle Ages. The main goal was to take back the Holy Land, especially Jerusalem, from Muslim control.

For hundreds of years, Jerusalem had been under Muslim rule. However, by the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks took over the area. This made it harder for Christians living there and for pilgrims traveling from Europe. It also threatened the Byzantine Empire.

The idea for the First Crusade began in 1095. The Byzantine emperor, Alexios I Komnenos, asked for military help from the Council of Piacenza to fight the Seljuk Turks. Later that year, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II supported this request. He also encouraged Christians to go on an armed journey to Jerusalem.

Many people across Western Europe were excited by this call. Thousands of mostly poor Christians, led by a French priest named Peter the Hermit, were the first to respond. This group became known as the People's Crusade. As they traveled through Germany, they attacked Jewish communities in what became known as the Rhineland massacres. When they left Byzantine land in Anatolia, the Seljuk leader Kilij Arslan I ambushed and destroyed them at the Battle of Civetot in October 1096.

Later, in late summer 1096, powerful nobles and their armies set off. This was called the Princes' Crusade. They arrived in Constantinople between November 1096 and April 1097. These forces included leaders like Raymond IV of Toulouse, Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohemond of Taranto, and Robert Curthose. Including non-fighters, their total numbers might have been as high as 100,000 people.

The crusader armies slowly moved into Anatolia. While Kilij Arslan was away, the crusaders and the Byzantine navy captured Nicaea in June 1097. This was an early victory. In July, the crusaders won the Battle of Dorylaeum against Turkish mounted archers. After a difficult march, they began the Siege of Antioch, capturing the city in June 1098. They reached Jerusalem, then controlled by the Fatimids, in June 1099. The Siege of Jerusalem ended with the city being taken by force on July 15, 1099. Many of its residents were killed. A Fatimid counterattack was stopped at the Battle of Ascalon later that year, which ended the First Crusade. Most crusaders then went home.

Four Crusader states were set up in the Holy Land: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Tripoli. Crusaders stayed in the region until their last major stronghold fell in the Siege of Acre in 1291. After this, no major attempts were made to take back the Holy Land.

Contents

- Why the Crusade Happened

- The Call to Crusade

- Peter the Hermit and the People's Crusade

- From Clermont to Constantinople

- Siege of Nicaea

- Battle of Dorylaeum

- The Armenian Stopover

- Siege of Antioch

- From Antioch to Jerusalem

- Siege of Jerusalem

- Establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Battle of Ascalon

- What Happened Next

- Images for kids

- See also

Why the Crusade Happened

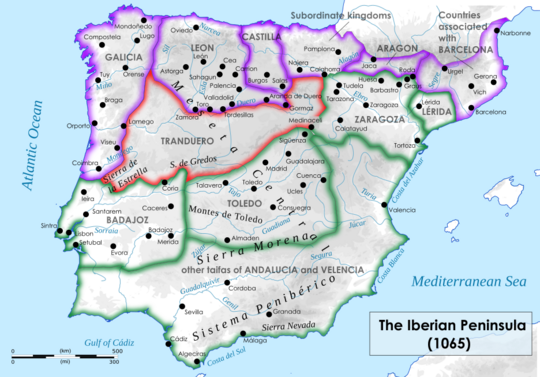

For a long time, Christian and Muslim states had been in conflict. After the Islamic prophet Muhammad died in 632, Muslim forces took over Jerusalem, the Levant, North Africa, and most of the Iberian Peninsula. These areas had been Christian before. By the 11th century, Christians were slowly taking back parts of Iberia in what was called the Reconquista.

However, their connection to the Holy Land became weaker. Muslim leaders in the Levant sometimes made it very hard for Christians to practice their faith openly. The First Crusade was a response from the Christian world to the expansion of Islam into the Holy Land and the Byzantine Empire.

In Western Europe, Jerusalem was seen as a very important place for pilgrimages. Even though the Seljuk Turks' control over Jerusalem was not strong (they later lost it to the Fatimids), pilgrims returning from the East reported difficulties and unfair treatment of Christians. The Byzantine Empire needed military help, and at the same time, Western European knights were more willing to follow the Pope's military orders.

Europe's Situation Before the Crusade

By the 11th century, Europe's population had grown a lot. New technologies and farming methods helped trade to grow. The Catholic Church had become very powerful in Western Europe. Society was organized by feudalism, where knights and nobles served their lords in exchange for land.

The Church wanted to increase its power and influence. This led to disagreements with Eastern Christians, especially about the idea of papal supremacy, which meant the Pope was the highest authority. The Eastern Church believed the Pope was just one of five important Church leaders. In 1054, differences in customs and beliefs led to a major split, known as the East–West Schism, between the Western and Eastern Churches.

Christians had a long history of using violence for community goals. A Christian idea of war developed, especially after Christianity became linked with Roman citizenship. Theologians like Augustine of Hippo in the 4th century developed the idea of a holy war. Augustine said that aggressive war was wrong, but war could be right if a leader like a king or bishop declared it. It also had to be for defense or to get back lost lands, and it should not involve too much violence.

The breakdown of the Carolingian Empire in Western Europe created many knights who often fought among themselves. The Pope tried to reduce this violence. Popes like Pope Alexander II and Pope Gregory VII developed ways to recruit soldiers using oaths. These methods were used in Christian conflicts with Muslims in Spain and for the Norman conquest of Sicily. Gregory VII even planned a holy war in 1074 to help Byzantium against the Seljuks, but he couldn't get enough support.

In Spain, Christian kingdoms like León and Navarre often united and split up. They developed strong military skills. In 1031, the Caliphate of Córdoba in southern Spain broke apart, allowing Christians to gain land. This became known as the Reconquista. In 1063, William VIII of Aquitaine led a force that captured the city of Barbastro from Muslims. This was supported by Pope Alexander II, who offered forgiveness of sins to those who took part. This was a holy war, but it was different from the First Crusade because there was no pilgrimage or formal church approval.

Situation in the East Before the Crusade

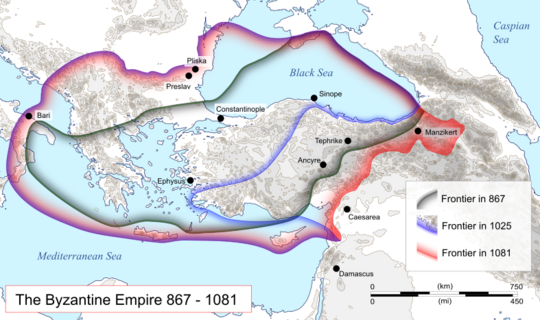

The Byzantine Empire was a rich and powerful center of culture. Under Emperor Basil II, the empire was at its largest in 1025. Its borders reached Iran, and it controlled Bulgaria and much of southern Italy. The empire faced challenges from various groups like the Normans in Italy and the Seljuk Turks in the east. To deal with these, emperors hired soldiers, sometimes even from their enemies.

The Islamic world also saw big changes. Waves of Turkic migration into the Middle East began in the 9th century. The arrival of the Seljuk Turks in the 10th century changed things even more. They were a small ruling family from Central Asia who converted to Islam. In a few decades, they conquered Iran, Iraq, and the Near East. The Seljuks were Sunni Muslims, which led to conflicts with the Shi'ite Fatimid Caliphate in Palestine and Syria.

The Seljuks were nomads and spoke Turkish, unlike their settled, Arabic-speaking subjects. This difference, along with their way of ruling based on family connections rather than geography, weakened their power. In 1071, Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes tried to stop Seljuk raids but was defeated at the Battle of Manzikert. This was a major setback for the Byzantines and led to significant Seljuk gains. Important cities like Nicaea and Antioch were lost in 1081 and 1086. These cities were well-known in the West and later became targets for the crusader armies.

After 1092, the situation in the Middle East became unstable. The powerful Seljuk ruler Nizam al-Mulk died, followed by the Seljuk sultan Malik-Shah and the Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir Billah. The Islamic world was in confusion and divided. When the First Crusade arrived, it was a surprise. Malik-Shah's son, Kilij Arslan, became ruler of the Sultanate of Rûm in Anatolia. His brother Tutush I started a civil war in Syria. When Tutush died in 1095, his sons Ridwan and Duqaq inherited Aleppo and Damascus, creating more divisions. Egypt and much of Palestine were controlled by the Fatimids. The Fatimids had lost Jerusalem to the Seljuks in 1073 but recaptured it in 1098, just before the crusaders arrived.

Hardships for Christians

Historians like Jonathan Riley-Smith and Rodney Stark say that Muslim authorities in the Holy Land often made it difficult for Christians to openly practice their faith. The persecution of Christians became worse after the Seljuk Turks invaded. Villages controlled by Turks along the route to Jerusalem began charging tolls to Christian pilgrims.

While the Seljuks generally allowed pilgrims to visit Jerusalem, they often demanded high fees and allowed local attacks. Many pilgrims were kidnapped and sold into slavery. Soon, only large, well-armed groups dared to make the journey, and even then, many died or turned back. Pilgrims who survived these dangerous trips returned to Europe tired and poor, with terrible stories to tell. News of these attacks on pilgrims and the persecution of Eastern Christians angered people in Europe.

The Call to Crusade

The main events that led to the First Crusade were the Council of Piacenza and the Council of Clermont, both held in 1095 by Pope Urban II. These councils led to Western Europe preparing to go to the Holy Land.

Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos was worried about the Seljuks moving into his lands. He sent messengers to the Council of Piacenza in March 1095 to ask Pope Urban for help. Urban responded positively. He might have hoped to heal the split between the Eastern and Western Churches that had happened 40 years earlier. He wanted to reunite the Church under the Pope's leadership by helping the Eastern Churches. Alexios and Urban had been in touch before and had discussed reuniting the Christian churches. There were signs of good cooperation between Rome and Constantinople just before the crusade.

In July 1095, Urban went to France to recruit men for the journey. His travels ended with the ten-day Council of Clermont. On November 27, he gave a powerful speech to many French nobles and clergy. We have five different versions of this speech, written by people who might have been there or who went on the crusade. These versions were written after Jerusalem was captured, so it's hard to know exactly what was said. The only records from that time are a few letters written by Urban in 1095.

The five versions of the speech are different in details, but they all agree on some key points. Urban talked about the violence in European society and the need for peace. He spoke about helping the Greeks, who had asked for aid. He also mentioned the crimes being committed against Christians in the East. He described a new kind of war, an armed pilgrimage, and promised rewards in heaven, including forgiveness of sins, for anyone who died on the journey. Not all versions specifically mention Jerusalem as the final goal. However, it's believed that Urban expected the expedition to reach Jerusalem all along. According to one version, the excited crowd shouted Deus lo volt!—meaning "God wills it!"

Peter the Hermit and the People's Crusade

The powerful French nobles and their trained knights were not the first to travel towards Jerusalem. Pope Urban had planned for the crusade to start on August 15, 1096. But months before this, groups of peasants and minor nobles set off on their own. They were led by a charismatic priest named Peter the Hermit. Peter was very good at spreading Urban's message, and he created great excitement among his followers. It is often thought that Peter's followers were only untrained peasants who didn't even know where Jerusalem was. However, there were also many knights among them, including Walter Sans Avoir, who led a separate army.

Peter's army lacked military training and quickly ran into trouble, even while still in Christian lands. Walter's army looted areas around Belgrade and Zemun but reached Constantinople with little trouble. Peter's army, marching separately, also fought with Hungarians. At Niš, the Byzantine governor tried to provide supplies, but Peter couldn't control his followers, and Byzantine troops had to stop their attacks. Peter arrived in Constantinople in August, where his army joined Walter's and other groups from France, Germany, and Italy.

Peter's and Walter's unruly crowd started to loot outside Constantinople for supplies. This made Emperor Alexios quickly move them across the Bosporus to Asia Minor. Once there, the crusaders split up and began looting the countryside, entering Seljuk territory near Nicaea. The experienced Turks killed most of this group. Some Italian and German crusaders were defeated at the Siege of Xerigordon in September. Walter and Peter's followers, though mostly untrained, fought the Turks at the Battle of Civetot in October 1096. Turkish archers destroyed the crusader army, and Walter was killed. Peter, who was in Constantinople at the time, later joined the second wave of crusaders.

In Europe, the call for the First Crusade also led to attacks on Jewish communities, known as the Rhineland massacres. In late 1095 and early 1096, months before the official crusade began, Jewish communities in France and Germany were attacked. In May 1096, Emicho of Flonheim attacked Jews in Speyer and Worms. Other unofficial crusaders joined Emicho in destroying the Jewish community of Mainz.

King Coloman of Hungary had to deal with problems caused by crusader armies marching through his country. He defeated two groups that were looting his kingdom. Emicho's army also entered Hungary but was defeated by Coloman, and Emicho's followers scattered. Many attackers seemed to want to force Jews to convert, but they also wanted their money. Physical violence against Jews was not part of the Church's official policy for crusading. Christian bishops tried their best to protect the Jews. However, some bishops also took money in exchange for protection. The attacks might have come from the belief that Jews and Muslims were both enemies of Christ and should be fought or converted.

From Clermont to Constantinople

The four main crusader armies left Europe around August 1096. They took different paths to Constantinople, some through Eastern Europe and the Balkans, others by crossing the Adriatic Sea. King Coloman of Hungary allowed Godfrey and his troops to cross Hungary only after Godfrey's brother, Baldwin, was given as a hostage to ensure good behavior. The armies gathered outside the Walls of Constantinople between November 1096 and April 1097.

Recruiting the Armies

Recruiting for such a large effort happened across the entire continent. Estimates suggest that between 70,000 and 80,000 people left Western Europe in the year after Clermont, and more joined later. The number of knights is estimated to be between 7,000 and 10,000, with 35,000 to 50,000 foot soldiers. Including non-fighters, the total could have been 60,000 to 100,000.

Pope Urban's speech was well-planned. He had discussed the crusade with Adhemar of Le Puy and Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse. These two important leaders from southern France quickly supported the expedition. Adhemar was at the council and was the first to "take the cross," meaning he vowed to go on the crusade. Throughout 1095 and 1096, Urban spread the message across France and urged his bishops to preach in their own areas.

The response to the speech was much greater than even the Pope expected. Urban tried to stop certain people, like women, monks, and the sick, from joining, but it was almost impossible. In the end, most who answered the call were not knights but peasants who were not wealthy and had little fighting skill. This showed a new, strong personal religious feeling that was hard for the Church leaders to control. Typically, preaching ended with each volunteer vowing to complete a pilgrimage to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. They were also given a cross, usually sewn onto their clothes.

It's hard to know why thousands of people joined, especially those whose stories weren't recorded. Even for important knights, their reasons were often retold by monks. It's very likely that personal religious belief was a major reason for many crusaders.

Even with this popular excitement, Urban made sure there would be an army of knights from the French nobility. Besides Adhemar and Raymond, other leaders he recruited included Bohemond of Taranto, his nephew Tancred, Godfrey of Bouillon, and his brother Baldwin of Boulogne. Also, Hugh I, Count of Vermandois, brother of the King of France, and Robert Curthose, brother of the King of England, joined. The crusaders came from northern and southern France, Flanders, Germany, and southern Italy. They were divided into four separate armies that didn't always work together, but they were united by their shared goal.

The crusade was led by some of France's most powerful nobles, many of whom left everything behind. Often, entire families went on crusade at their own great expense. For example, Robert of Normandy loaned his duchy to his brother, and Godfrey sold or mortgaged his property. For some, like Bohemond, personal gain played a role. He wanted to create his own territory in the East. The crusade gave him this chance, and he took control of Antioch, establishing the Principality of Antioch.

The Journey to Constantinople

The armies traveled to Constantinople by different routes. Godfrey took the land route through the Balkans. Raymond of Toulouse led his forces along the coast of Illyria and then east to Constantinople. Bohemond and Tancred led their Normans by sea to Durazzo and then by land.

The armies arrived in Constantinople with little food, expecting supplies and help from Emperor Alexios. Alexios was suspicious because of his experiences with the People's Crusade. Also, the knights included his old enemy, Bohemond, who had invaded Byzantine territory before. This time, Alexios was better prepared, and there were fewer violent incidents along the way.

The crusaders might have expected Alexios to lead them, but he wasn't interested. He mainly wanted to move them into Asia Minor as quickly as possible. In exchange for food and supplies, Alexios asked the leaders to promise loyalty to him. They also had to promise to return any land taken from the Turks to the Byzantine Empire. Godfrey was the first to take this oath, and most other leaders followed. Raymond alone avoided the oath, promising only not to harm the empire. Before sending the armies across the Bosporus, Alexios advised the leaders on how to fight the Seljuk armies they would soon meet.

Siege of Nicaea

The Crusader armies crossed into Asia Minor in the first half of 1097. They were joined by Peter the Hermit and the few survivors of his army. Emperor Alexios also sent two of his generals, Manuel Boutoumites and Tatikios, to help the crusaders.

Their first target was Nicaea, a city that used to be under Byzantine rule. It had become the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm under Kilij Arslan. Arslan was away fighting elsewhere and had left his treasury and family behind, not realizing how strong these new crusaders were.

When the Crusaders arrived on May 14, 1097, they began to besiege the city. When Arslan heard about it, he rushed back to Nicaea and attacked the crusader army on May 16. He was pushed back by the surprisingly large crusader force, and both sides suffered heavy losses. The siege continued, but the crusaders had trouble because they couldn't block Lake İznik, which the city was on. Supplies could still reach the city by water. To capture the city, Alexios had the Crusaders' ships moved over land on logs. When the Turkish defenders saw the ships on the lake, they finally surrendered on June 18.

Some of the Franks (Western Europeans) were unhappy because they were not allowed to loot the city. Alexios made up for this by paying the crusaders. Later stories sometimes make the tension between the Greeks and Franks seem worse than it was. However, a letter from Stephen of Blois to his wife confirms that there was still good cooperation at this point. The fall of Nicaea is seen as a rare example of close teamwork between the Crusaders and the Byzantines.

Battle of Dorylaeum

At the end of June, the crusaders marched through Anatolia. Some Byzantine troops under Tatikios went with them. The crusaders still hoped that Alexios would send a full Byzantine army to join them. They split their army into two easier-to-manage groups: one led by the Normans, the other by the French. The two groups planned to meet again at Dorylaeum.

On July 1, the Normans, who had marched ahead, were attacked by Kilij Arslan. Arslan had gathered a much larger army after his defeat at Nicaea. He surrounded the Normans with his fast-moving mounted archers. The Normans formed a tight defensive circle, protecting their equipment and non-fighters, and sent for help. When the French arrived, Godfrey broke through the Turkish lines, and the Church leader Adhemar attacked the Turks from behind. The Turks had expected to destroy the Normans and didn't expect the French to arrive so quickly. They fled rather than face the combined crusader army.

After this, the crusaders' march through Anatolia was unopposed. However, the journey was difficult because Arslan had burned and destroyed everything as his army fled. It was mid-summer, and the crusaders had very little food and water. Many men and horses died. Sometimes, other Christians gave them food and money. But more often, the crusaders simply looted whenever they could. The individual leaders continued to argue about who should be in charge, but none were powerful enough to take full command. Adhemar was always seen as the spiritual leader.

The Armenian Stopover

After passing through the Cilician Gates, Baldwin and Tancred left the main army. They headed towards the Armenian lands. Baldwin wanted to create his own territory in the Holy Land. In Armenia, he could count on support from the local people. Baldwin and Tancred led two separate groups, leaving Heraclea on September 15.

Tancred arrived first at Tarsus. He convinced the Seljuk soldiers there to raise his flag. Baldwin reached Tarsus the next day. The Turks allowed Baldwin to take control of two towers. Tancred, outnumbered, decided not to fight for the town. Soon after, a group of Norman knights arrived, but Baldwin wouldn't let them in. The Turks killed these Normans during the night. Baldwin's men blamed him and killed the remaining Seljuk soldiers. Baldwin took shelter in a tower and convinced his soldiers he was innocent. A pirate captain, Guynemer of Boulogne, sailed to Tarsus and swore loyalty to Baldwin. Baldwin hired Guynemer's men to guard the city while he continued his campaign.

Tancred had captured the town of Mamistra. Baldwin reached Mamistra around September 30. A Norman knight, Richard of Salerno, wanted revenge for Tarsus, which caused a fight between Baldwin's and Tancred's soldiers. Baldwin left Mamistra and joined the main army at Marash. But a local Armenian, Bagrat, convinced him to campaign in an area with many Armenians. Baldwin left the main army on October 17. The Armenians welcomed Baldwin, and the local people killed the Seljuks, taking the fortresses of Ravendel and Turbessel by the end of 1097. Baldwin made Bagrat the governor of Ravendel.

The Armenian lord Thoros of Edessa sent messengers to Baldwin in early 1098, asking for help against the Seljuks nearby. Before leaving for Edessa, Baldwin ordered Bagrat's arrest, accusing him of working with the Seljuks. Bagrat was forced to give up Ravendel. Baldwin left for Edessa in early February, being bothered by forces from Balduk, the emir of Samosata.

When he reached Edessa, Baldwin was welcomed by Thoros and the local Christians. Thoros even adopted Baldwin as his son, making him a co-ruler of Edessa. With troops from Edessa, Baldwin raided Balduk's territory and put soldiers in a small fortress near Samosata.

Soon after Baldwin returned, some local nobles started plotting against Thoros, probably with Baldwin's agreement. A riot broke out, forcing Thoros to hide in the castle. Baldwin promised to save his adoptive father, but when the rioters broke into the castle on March 9 and killed Thoros and his wife, Baldwin did nothing to stop them. The next day, the townspeople accepted Baldwin as their ruler. He took the title of Count of Edessa, creating the first of the Crusader states.

The Byzantines had lost Edessa to the Seljuks in 1087, but the emperor didn't demand that Baldwin hand over the town. Also, taking Ravendel, Turbessel, and Edessa helped the main crusader army later at Antioch. The lands along the Euphrates River provided food for the crusaders, and the fortresses made it harder for Seljuk troops to move around.

Because his army was small, Baldwin used diplomacy to secure his rule in Edessa. He married Arda of Armenia, who later became queen of Jerusalem. He encouraged his knights to marry local women. The city's wealth allowed him to hire soldiers and buy Samosata from Balduk. This agreement with Balduk was the first friendly deal between a crusader leader and a Muslim ruler.

A key figure later was Belek Ghazi, a grandson of a former Seljuk governor of Jerusalem. Belek, an Artuqid emir, hired Baldwin to stop a revolt in Saruj. When Muslim leaders in Saruj asked Balduk for help, Balduk rushed there. But his forces couldn't resist a siege, and the defenders surrendered to Baldwin. Baldwin demanded Balduk's wife and children as hostages. When Balduk refused, Baldwin captured and executed him. With Saruj, Baldwin had strengthened his county and secured his communication with the main crusader army.

Kerbogha, always trying to defeat the Crusaders, gathered a large army to eliminate Baldwin. On his way to Antioch, Kerbogha besieged Edessa for three weeks in May. But he couldn't capture it. This delay was very important for the Crusader victory at Antioch.

Siege of Antioch

The crusader army, without Baldwin and Tancred, marched to Antioch. This city was halfway between Constantinople and Jerusalem. Stephen of Blois described it as "a city very extensive, fortified with incredible strength and almost impregnable." The idea of taking the city by force was discouraging. The crusader army began a siege on October 20, 1097, hoping to force a surrender or find a traitor inside. Antioch was so large that the crusaders didn't have enough troops to surround it completely, so supplies could still get in. This Siege of Antioch has been called the "most interesting siege in history."

By January, the eight-month siege had caused hundreds, possibly thousands, of crusaders to die of starvation. Adhemar believed this was due to their sins, so they started fasting, praying, giving to charity, and holding processions. Women were sent out of the camp. Many soldiers deserted, including Stephen of Blois. Getting food from foraging, and supplies from Cilicia and Edessa through the captured ports of Latakia and St Symeon, helped the situation. In March, a small English fleet arrived with more supplies.

The Franks benefited from disagreements in the Muslim world. The Seljuk brothers, Duqaq of Syria and Ridwan of Aleppo, sent separate armies to help in December and February. If these armies had combined, they probably would have won.

After these failures, Kerbogha gathered a large army from southern Syria, northern Iraq, and Anatolia. He wanted to expand his power. His army first spent three weeks trying to recapture Saruj, which was a crucial delay.

Bohemond convinced the other leaders that if Antioch fell, he would keep it for himself. He also said that an Armenian commander of a part of the city's walls had agreed to let the crusaders in.

Stephen of Blois had deserted and told Emperor Alexios that the cause was lost. This convinced the Emperor to stop his advance through Anatolia and return to Constantinople. (Alexios' failure to reach the siege was later used by Bohemond to justify not returning the city to the Empire, as he had promised.)

The Armenian Firouz helped Bohemond and a small group enter the city on June 2 and open a gate. Horns were sounded, the city's Christian majority opened other gates, and the crusaders entered. During the attack, they killed most of the Muslim residents and many Christian Greeks, Syrians, and Armenians in the confusion.

On June 4, the first part of Kerbogha's 40,000-strong army arrived, surrounding the Franks. From June 10 for four days, Kerbogha's men attacked the city walls from dawn until dusk. Bohemond and Adhemar blocked the city gates to prevent soldiers from running away, and they managed to hold out. Kerbogha then changed tactics to try to starve the crusaders out.

Morale inside the city was low, and defeat seemed certain. But a peasant named Peter Bartholomew claimed that the apostle St. Andrew appeared to him and showed him where the Holy Lance was. This was said to have encouraged the crusaders, but it was two weeks before the final battle. On June 24, the Franks asked for terms of surrender, but they were refused. On June 28, 1098, at dawn, the Franks marched out of the city in four groups to fight the enemy. Kerbogha allowed them to spread out, planning to destroy them in the open. However, the Muslim army's discipline broke, and a disorganized attack began. Unable to defeat a tired force they outnumbered two-to-one, the Muslims fled. With very few losses for the crusaders, the Muslim army broke and ran from the battle.

Stephen of Blois was in Alexandretta when he heard about the situation in Antioch. It seemed hopeless, so he left the Middle East, warning Alexios and his army on his way back to France. Because of what looked like a huge betrayal, the leaders at Antioch, especially Bohemond, argued that Alexios had abandoned the Crusade. This meant their oaths to him were no longer valid. While Bohemond claimed Antioch for himself, not everyone agreed (especially Raymond of Toulouse). So, the crusade was delayed for the rest of the year while the nobles argued. Some historians believe that the different groups of Franks, Provençals, and Normans saw themselves as separate nations, causing conflict as each tried to gain power. Others argue that personal ambition among the Crusader leaders was also to blame.

Meanwhile, a plague broke out, killing many in the army, including the Church leader Adhemar, who died on August 1. There were even fewer horses, and Muslim peasants in the area refused to give the crusaders food. The ordinary soldiers became very restless and threatened to go to Jerusalem without their arguing leaders. Finally, in early 1099, the march restarted. Bohemond stayed behind as the first Prince of Antioch.

From Antioch to Jerusalem

As they moved down the Mediterranean coast, the crusaders met little resistance. Local rulers preferred to make peace and provide supplies rather than fight. Their forces changed, with Robert Curthose and Tancred agreeing to serve Raymond IV of Toulouse, who was rich enough to pay them. Godfrey of Bouillon, now supported by his brother's lands in Edessa, refused to do the same. In January, Raymond destroyed the walls of Ma'arrat al-Numan. He then began the march south to Jerusalem, barefoot and dressed as a pilgrim, followed by Robert and Tancred and their armies.

Raymond planned to take Tripoli to set up a state like Antioch. But first, he started a siege of Arqa, a city in northern Lebanon, on February 14, 1099. Meanwhile, Godfrey, along with Robert II of Flanders (who also refused to serve Raymond), joined the remaining Crusaders at Latakia and marched south in February. Bohemond had originally marched with them but quickly returned to Antioch to strengthen his rule against the Byzantines. Tancred left Raymond's service and joined Godfrey. Another force linked to Godfrey's was led by Gaston IV of Béarn.

Godfrey, Robert, Tancred, and Gaston arrived at Arqa in March, but the siege continued. Pons of Balazun died, hit by a stone. The situation was tense not only among the military leaders but also among the clergy. Since Adhemar's death, there had been no clear leader for the crusade. And ever since the discovery of the Holy Lance, there had been accusations of fraud among the Church groups. On April 8, Arnulf of Chocques challenged Peter Bartholomew to a trial by fire. Peter went through the trial and died days later from his wounds. This made the Holy Lance seem like a fake. This also weakened Raymond's authority, as he was the main supporter of its truthfulness.

The siege of Arqa lasted until May 13, when the Crusaders left without capturing anything. The Fatimids had recaptured Jerusalem from the Seljuks the year before. They tried to make a deal with the Crusaders, promising free passage to pilgrims if the Crusaders didn't advance into their lands. But this was rejected. The Fatimid governor of Jerusalem, Iftikhar al-Dawla, knew the Crusaders' plans. So, he expelled all of Jerusalem's Christian residents. He also poisoned most of the wells in the area.

On May 13, the Crusaders came to Tripoli. The emir Jalal al-Mulk Abu'l Hasan provided the Crusader army with horses and promised to convert to Christianity if the Crusaders defeated the Fatimids. Continuing south along the coast, the Crusaders passed Beirut on May 19 and Tyre on May 23. Turning inland at Jaffa, on June 3 they reached Ramla, which its residents had abandoned. The bishopric of Ramla-Lydda was established there at the Church of St. George before they continued to Jerusalem. On June 6, Godfrey sent Tancred and Gaston to capture Bethlehem. Tancred put his banner over the Church of the Nativity. On June 7, the Crusaders reached Jerusalem. Many Crusaders cried when they saw the city they had traveled so long to reach.

Siege of Jerusalem

When the Crusaders arrived at Jerusalem, they found a dry landscape with little water or food. There was no hope of getting help, and they feared an attack from the local Fatimid rulers. They couldn't blockade the city like they did at Antioch because they didn't have enough troops, supplies, or time. Instead, they decided to attack the city directly. They might have had no other choice, as by the time they reached Jerusalem, it's estimated only about 12,000 men, including 1,500 cavalry, remained. This began the important Siege of Jerusalem.

These groups, made of men from different places with different loyalties, were also having trouble getting along. Godfrey and Tancred camped north of the city, while Raymond camped to the south. The Provençal group didn't take part in the first attack on June 13, 1099. This first attack was more of a test than a determined effort. After climbing the outer wall, the Crusaders were pushed back from the inner one.

After the first attack failed, the leaders met and agreed that a more organized attack was needed. On June 17, a group of Genoese sailors led by Guglielmo Embriaco arrived at Jaffa. They provided the Crusaders with skilled engineers and, more importantly, timber from their ships to build siege engines. The Crusaders' spirits were lifted when a priest named Peter Desiderius claimed to have had a vision from Adhemar of Le Puy. The vision told them to fast and then march barefoot around the city walls, after which the city would fall, just like in the Biblical story of the battle of Jericho. After a three-day fast, on July 8, the Crusaders performed the procession as instructed. They ended on the Mount of Olives, where Peter the Hermit preached to them. Soon after, the arguing groups publicly made peace. News then arrived that a Fatimid army was coming from Egypt to help Jerusalem, giving the Crusaders a strong reason to attack the city again.

The final attack on Jerusalem began on July 13. Raymond's troops attacked the south gate, while the other groups attacked the northern wall. At first, the Provençals at the southern gate made little progress. But the groups at the northern wall did better, slowly weakening the defense. On July 15, a final push was launched at both ends of the city. Eventually, the inner wall of the northern side was captured. In the panic, the defenders abandoned the city walls at both ends, allowing the Crusaders to finally enter.

The killing that followed the capture of Jerusalem is well-known. Eyewitness accounts from the crusaders themselves confirm that many people were killed after the siege. However, some historians suggest that the scale of the killing has been exaggerated in later medieval writings.

After the successful attack on the northern wall, the defenders fled to the Temple Mount. Tancred and his men chased them. Arriving before the defenders could secure the area, Tancred's men attacked, killing many defenders. The rest took refuge in the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Tancred then stopped the killing, offering protection to those in the mosque. When the defenders on the southern wall heard that the northern wall had fallen, they fled to the citadel. This allowed Raymond and the Provençals to enter the city. Iftikhar al-Dawla, the commander of the garrison, made a deal with Raymond. He surrendered the citadel in return for safe passage to Ascalon.

The killing continued for the rest of the day. Muslims were killed without distinction, and Jews who had hidden in their synagogue died when it was burned down by the Crusaders. The next day, Tancred's prisoners in the mosque were killed. However, it is clear that some Muslims and Jews in the city survived, either by escaping or by being taken prisoner to be ransomed. The Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon describes how Jews from Ascalon made great efforts to ransom Jewish captives and send them to safety in Alexandria. The Eastern Christian population of the city had been expelled by the governor before the siege, so they escaped the killing.

Establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem

On July 22, a meeting was held in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to decide how Jerusalem would be governed. Since the Greek Patriarch had died, there was no clear Church leader to establish a religious government, which some people wanted. Although Raymond of Toulouse was a leading crusader from 1098, his support had decreased after his failed attempts to besiege Arqa and create his own territory. This might be why he humbly refused the crown, saying it could only be worn by Christ. It might also have been an attempt to convince others to reject the title, but Godfrey was already familiar with such a position.

More likely, the presence of the large army from Lorraine, led by Godfrey and his brothers, Eustace and Baldwin, helped. Godfrey was then chosen as leader. He accepted the title Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri or Defender of the Holy Sepulchre. Raymond, angry about this, tried to seize the Tower of David before leaving the city.

Pope Urban II died on July 29, 1099, just 14 days after Jerusalem was captured, but before the news reached Rome. He was followed by Pope Paschal II, who served for almost 20 years.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem would last until 1291. However, the city of Jerusalem itself was lost to the Muslims under Saladin in 1187, after the important Battle of Hattin. The city of Jerusalem would remain under Muslim rule for 40 years, finally returning to Christian control after later Crusades.

Battle of Ascalon

In August 1099, the Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah landed an army of 20,000 North Africans at Ascalon. Godfrey and Raymond marched out to meet this force on August 9 at the Battle of Ascalon. They had only 1,200 knights and 9,000 foot soldiers. Even though they were outnumbered two to one, the Franks launched a surprise dawn attack and defeated the overconfident Muslim force.

However, the opportunity was missed. Arguments between Raymond and Godfrey prevented the city's defenders from surrendering to Raymond, whom they trusted more. The crusaders had won a clear victory, but the city remained in Muslim hands and was a military threat to the new kingdom.

What Happened Next

Most crusaders now felt their pilgrimage was complete and went home. Only about 300 knights and 2,000 foot soldiers stayed to defend Palestine. It was the support of the knights from Lorraine that helped Godfrey become the leader of Jerusalem, over Raymond's claims. When Godfrey died a year later, these same Lorrainers stopped the Pope's representative, Dagobert of Pisa, from making Jerusalem a religious state. Instead, they made Baldwin the first Latin king of Jerusalem.

Bohemond returned to Europe to fight the Byzantines from Italy but was defeated in 1108. After Raymond's death, his family captured Tripoli in 1109 with help from Genoa. Relations between the new Crusader states of the County of Edessa and the Principality of Antioch varied. They fought together in the crusader defeat at the Battle of Harran in 1104. But the Antiocheans claimed control and blocked the return of Baldwin II of Jerusalem after he was captured. The Franks became deeply involved in Middle Eastern politics, often fighting against Muslims and sometimes even against each other. Antioch's expansion ended in 1119 with a major defeat to the Turks at the Battle of Ager Sanguinis, also known as the Field of Blood.

Many people had gone home before reaching Jerusalem, and many had never left Europe at all. When the Crusade's success became known, these people were mocked by their families and threatened with excommunication by the Pope. Back home in Western Europe, those who had survived to reach Jerusalem were treated as heroes. Robert II of Flanders was nicknamed Hierosolymitanus (meaning "of Jerusalem") because of his actions. Among those who took part in the later Crusade of 1101 were Stephen of Blois and Hugh of Vermandois, both of whom had returned home before reaching Jerusalem. This crusader force was almost destroyed in Asia Minor by the Seljuks, but the survivors helped strengthen the kingdom when they arrived in Jerusalem.

There is not much written evidence of the Islamic reaction from before 1160. What exists suggests the crusade was barely noticed. This might be because the Turks and Arabs didn't see the crusaders as religiously motivated warriors seeking to conquer and settle. They might have thought the crusaders were just the latest in a long line of Byzantine hired soldiers. Also, the Islamic world was divided among rival rulers in Cairo, Damascus, Aleppo, and Baghdad. There was no unified Muslim counter-attack, which allowed the crusaders to establish their new states.

Images for kids

-

Anatolian Seljuk horseman, in Varka and Golshah, mid-13th century miniature (detail), Konya, Sultanate of Rum.

-

Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont. Illustration from a copy of Sébastien Mamerot's Livre des Passages d'Outremer (Jean Colombe, c. 1472–75, BNF Fr. 5594)

-

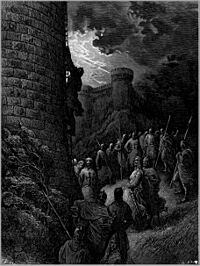

An illustration showing the defeat of the People's Crusade, from Sébastien Mamerot's Livre des Passages d'Outre-mer (Jean Colombe, c. 1472–75, BNF Fr. 5594)

-

Siege of Nicaea in 1097. Miniature from Roman de Godefroy de Bouillon et de Saladin

-

Baldwin of Boulogne entering Edessa in 1098 (history painting by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury, 1840)

-

Bohemond of Taranto Alone Mounts the Rampart of Antioch, by Gustave Doré (1871)

-

The Siege of Jerusalem as depicted in a medieval manuscript

-

Crusader graffiti in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem

-

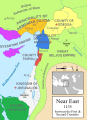

The Crusader states between the First and Second Crusades

See also

In Spanish: Primera cruzada para niños

In Spanish: Primera cruzada para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |