Bohemond I of Antioch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bohemond I |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Prince of Antioch | |

| Reign | 1098–1111 |

| Successor | Bohemond II |

| Regent | Tancred of Hauteville |

| Prince of Taranto | |

| Reign | 1088–1111 |

| Predecessor | Robert Guiscard |

| Successor | Bohemond II |

| Born | c. 1054 San Marco Argentano, Calabria, County of Apulia and Calabria |

| Died | 5 or 7 March 1111 (56-57) Canosa di Puglia, County of Apulia and Calabria |

| Burial | Canosa di Puglia Mausoleum |

| Spouse | Constance of France |

| Issue | Bohemond II of Antioch |

| House | Hauteville |

| Father | Robert Guiscard |

| Mother | Alberada of Buonalbergo |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Bohemond I of Antioch (born around 1054, died March 5 or 7, 1111) was a powerful Norman leader. He was known as the Prince of Taranto from 1089 to 1111 and the first Prince of Antioch from 1098 to 1111. Bohemond was a key leader in the First Crusade, guiding a group of Normans on their journey to the East. He knew a lot about the Byzantine Empire from earlier battles with his father. This made him the most experienced military leader among the crusaders.

Contents

Early Life of Bohemond

Childhood and Family

Bohemond was born between 1050 and 1058, likely in 1054. His father was Robert Guiscard, a powerful Norman count. His mother was Alberada of Buonalbergo. He was probably born at his father's castle in San Marco Argentano, Italy.

When Bohemond was young, his parents' marriage was ended. This was because they were related in a way that was not allowed by church law at the time. His father then married Sikelgaita, a princess from Salerno. Bohemond's mother made sure he received a good education in knighthood. Bohemond was very good with languages. He spoke his native Norman language. He also likely understood or spoke "Lombard Italian" and could speak or even read Greek.

In 1073, his father, Robert Guiscard, became very ill. Robert's wife, Sikelgaita, wanted her son, Roger Borsa, to be the next ruler. She convinced many nobles to support Roger. Bohemond, however, believed he should be his father's heir.

Battles Against the Byzantines

Bohemond fought in his father's army in 1079. In 1081, he led a group against the Byzantine Empire. He captured a town called Valona in modern-day Albania. He also sailed to Corfu but did not attack the island. Later, he and his father laid siege to Dyrrhachium (now Durrës). On October 18, the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos tried to help the town but was badly defeated. Bohemond led the left side of the Norman army. His group defeated the Emperor's special guards.

The Normans captured Dyrrhachium in February 1082. They marched into Macedonia and Thessaly. However, their long siege of Larissa failed. The Norman army faced problems with supplies and pay. Many soldiers left, so Bohemond went back to Italy for money. While he was gone, most Norman leaders joined the Byzantines. A Venetian fleet also took back Dyrrhachium and Corfu.

Bohemond went with his father to the Byzantine Empire again in 1084. They defeated the Venetian fleet and captured Corfu. But a sickness spread among the Normans. Bohemond became very ill and had to return to Italy in December 1084.

Family Power Struggles

Robert Guiscard died in July 1085. Many people thought his wife, Sikelgaita, had poisoned him. She wanted her son, Roger Borsa, to become the ruler of Apulia. The army and nobles supported Roger. But Bohemond felt he was the rightful heir.

Bohemond made an alliance with another Norman leader. He captured the towns of Oria and Otranto. Bohemond and Roger Borsa met to make a deal. Bohemond received several towns, including Taranto and Brindisi. In return, he accepted Roger Borsa as the main ruler.

However, Bohemond started fighting his brother again in 1087. This civil war weakened the Normans. It also allowed their uncle, Roger I of Sicily, to become more powerful. Bohemond captured Bari in 1090. Soon, he controlled most of the lands south of Melfi.

Bohemond's Appearance

Anna Komnene, a Byzantine princess, wrote about how Bohemond looked. She said he was taller than most men, almost a foot taller. He was slender around his waist but had broad shoulders and a strong chest. His arms were powerful. He was well-built, not too thin or too heavy.

His skin was very pale, but his face had some color. His hair was light-colored and cut short, not long like other barbarians. His beard was shaved very close, making his chin smooth. His eyes were light-blue and showed his strong spirit and dignity. He had a strong nose and chest. Anna Komnene also noted that he had a certain charm, but also a scary look about him. She felt he was brave and passionate, always ready for war. He was also clever and good at finding solutions to problems.

The First Crusade

In 1097, Bohemond and his uncle were attacking a city when groups of crusaders started passing through Italy. Bohemond may have joined the First Crusade for religious reasons. But it is also likely he saw a chance to gain new lands in the Middle East. Some historians believe he joined to conquer lands from the Byzantine Empire.

Bohemond gathered a Norman army. It was one of the smaller crusade forces, with about 500 knights and 2,500 to 3,500 foot soldiers. His nephew, Tancred, also brought 2,000 men. The Norman army was known for its fighting skills. Many Normans had worked as soldiers for the Byzantine Empire. Others, like Bohemond, had fought the Byzantines and Muslim groups before.

Bohemond traveled to Constantinople, following a route he had used in earlier battles. He was careful to keep his soldiers from stealing from Byzantine villages along the way. This was important to show respect to Emperor Alexios.

Meeting Emperor Alexios

When Bohemond arrived in Constantinople in April 1097, he took an oath of loyalty to Emperor Alexios. The Emperor asked all crusade leaders to do this. Alexios did not fully trust Bohemond. But he hinted that Bohemond could gain a position if he proved his loyalty. Bohemond was good at Greek, so he helped communicate between Alexios and the other crusade leaders. He also tried to convince other leaders to take the oath.

From Constantinople to Antioch, Bohemond stood out among the crusade leaders. He was known as a skilled planner and leader. He had learned about Byzantine and Muslim fighting methods from his past battles. This knowledge helped him adapt quickly and led to victories for the crusaders.

Siege of Antioch

Bohemond saw a chance to use the crusade for his own goals at the siege of Antioch. He was the first to set up camp outside Antioch in October 1097. During the siege, he played a key role. He helped gather supplies and stopped an enemy army from reaching the city. He also connected the crusaders with a fleet of ships. Because of his success, Bohemond was seen as the real leader of the siege.

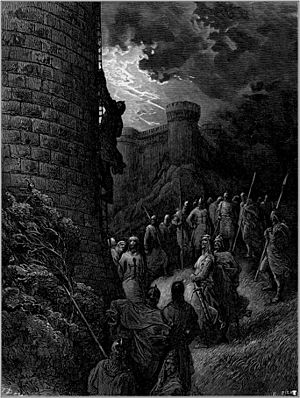

Bohemond made a secret deal with Firouz, a commander of the city wall. He waited until May 1098 to act, when he learned that a large enemy army was coming. He then suggested to the other crusade leaders that whoever captured Antioch should rule it. Firouz helped Bohemond's forces climb the walls. This allowed the Norman soldiers to enter and capture the city.

The crusaders' problems were not over. A new enemy leader, Kerbogha, began his own siege of Antioch. Bohemond was praised for planning the battle that defeated Kerbogha. The crusaders were running low on food. Bohemond led his army out of the city and attacked Kerbogha's forces. This led to a big victory for the crusaders.

Bohemond then wanted to take control of Antioch for himself. Another crusade leader, Raymond of Toulouse, disagreed. Raymond said Bohemond would be breaking his oath to Alexios. The oath was to give any conquered lands to the Byzantine Empire. Bohemond argued that Alexios had not helped the crusaders at Antioch, so the oath was no longer valid. Bohemond became the Prince of Antioch. No other crusader or Byzantine force tried to take it from him. Raymond of Toulouse finally gave up Antioch to Bohemond in January 1099. The other crusaders then moved south to capture Jerusalem.

After Jerusalem was captured, Bohemond tried to besiege a Byzantine fort. But other crusade leaders made him stop. Bohemond went to Jerusalem in December 1099 to complete his crusade vows. He helped install a new church leader there. This helped him make connections in Jerusalem, which could be an ally for Antioch. Bohemond had a good territory and army for his new principality. But he faced two big challenges: the Byzantine Empire and strong Muslim rulers in Syria. He would eventually struggle against these forces.

Wars Between Antioch and the Byzantine Empire

In 1100, Bohemond received a request for help from an Armenian leader. This leader controlled an important city and feared an attack. The Armenians offered Bohemond their daughter in marriage if he helped.

Bohemond did not want to weaken his forces in Antioch. But he also wanted to expand his lands. So, in August 1100, he marched north with only 300 knights and a small group of foot soldiers. They were ambushed by the Turks and surrounded. Bohemond was captured and held prisoner until 1103.

Emperor Alexios was angry that Bohemond had broken his oath and kept Antioch. When he heard Bohemond was captured, he offered a large sum of money to free him. But Bohemond offered a smaller ransom directly to his captor. The deal was made, and Bohemond was freed in August 1103.

His nephew Tancred had ruled Antioch for three years while Bohemond was away. Tancred had attacked the Byzantines and added more land to Antioch. When Bohemond returned, Tancred lost his rule. In 1104, Bohemond and another leader attacked an eastern city.

During this campaign, Bohemond was defeated in a battle near Raqqa. This defeat made it impossible for him to create a large eastern principality. After this, the Greeks attacked his lands. Feeling he did not have enough resources, Bohemond returned to Europe in late 1104 to get more soldiers.

He traveled across France, telling stories of his bravery and showing relics from the Holy Land. He gathered a large army. His new fame helped him marry Constance, the daughter of the French king, Philip I. They had a son named Bohemond II of Antioch.

Bohemond believed Emperor Alexios and Constantinople were the main problems for his rule in Antioch. In 1106, Bohemond gave a speech. He accused the emperor of harming many Christians and being a "mad heretic."

Bohemond decided to use his new army of 34,000 men to attack Alexios, not to defend Antioch. He took a similar route that his father had used before. But Alexios, with help from the Venetians, was much stronger this time. Alexios knew Norman fighting tactics. He chose to wear down Bohemond's army instead of fighting them directly. During the Norman siege of Dyrrhachium in 1107–1108, Alexios blocked the Norman camp. Bohemond was forced to negotiate.

Bohemond had to agree to a difficult peace treaty, called the Treaty of Deabolis, in 1108. He became a vassal (a loyal servant) of Alexios. He agreed to receive Alexios's pay and give up disputed lands. He also promised to allow a Greek church leader in Antioch. After this, Bohemond was a broken man. He died six months later without returning to Antioch. Because he did not return, the treaty became invalid. Antioch remained in Norman hands, ruled by Bohemond's nephew, Tancred.

Bohemond was buried in Canosa di Puglia in Italy in 1111.

Bohemond I in Books and Movies

The Gesta Francorum is a book written by one of Bohemond's followers. The Alexiad by Anna Comnena is an important source about his life. There are also other historical books that talk about him.

Bohemond is a character in several historical novels. These include Count Bohemund by Alfred Duggan (1964) and Silver Leopard by F. Van Wyck Mason (1955). He also appears in the short story "The Track of Bohemond" by Robert E. Howard and the novel Pilgermann by Russell Hoban.

The novel Wine of Satan (1949) by Laverne Gay tells an exciting story about Bohemond's life.

In the Crusades book series by David Donachie (writing as Jack Ludlow), Bohemond is the main hero.

Bohemond is also featured in the video game Age of Empires II: Lords of the West. He has two campaigns about his victories and his defense of Antioch.

|

See also

In Spanish: Bohemundo de Tarento para niños

In Spanish: Bohemundo de Tarento para niños