Treaty of Devol facts for kids

The Treaty of Deabolis was an agreement made in 1108. It was signed between Bohemond I of Antioch and the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. This happened after the First Crusade. The treaty gets its name from the Byzantine fortress of Deabolis. Today, this place is called Devol in Albania.

The treaty was meant to make the Principality of Antioch a vassal state. This means Antioch would be under the control of the Byzantine Empire. However, the treaty was not put into action right away.

At the start of the First Crusade, Crusader armies gathered at Constantinople. They promised to give back any land they conquered to the Byzantine Empire. But Bohemond, whose father was an enemy of Alexios, claimed the Principality of Antioch for himself.

Alexios did not agree that Bohemond had the right to rule Antioch. So, Bohemond went to Europe to find more soldiers. He then started a war against Alexios. He attacked Dyrrhachium, but he was soon forced to give up. He had to talk with Alexios at the imperial camp in Deabolis. This is where the treaty was signed.

Under the treaty, Bohemond agreed to become a loyal follower of the Emperor. He also promised to defend the Empire whenever it needed help. He accepted that a Greek Christian leader would be appointed in Antioch. In return, Bohemond received special titles like sebastos and doux (duke) of Antioch. He was also allowed to pass on the County of Edessa to his children.

After this, Bohemond went back to Apulia and died there. His nephew, Tancred, was ruling Antioch at the time. Tancred refused to accept the treaty's terms. Antioch briefly came under Byzantine control in 1137. But it truly became a Byzantine vassal only in 1158.

The Treaty of Deabolis shows how the Byzantines often preferred to solve problems through talking rather than fighting. It also caused and was caused by the lack of trust between the Byzantines and their neighbors in Western Europe.

Why the Treaty Was Needed

In 1097, Crusader armies arrived in Constantinople. They had traveled from Europe. Emperor Alexios I had only asked for some western knights. He wanted them to be soldiers for hire to fight the Seljuk Turks.

Alexios kept these armies in the city. He would not let them leave until their leaders swore oaths. These oaths promised to return any conquered land that used to belong to the Byzantine Empire. The Crusaders eventually swore these oaths.

Alexios then gave them guides and soldiers to help them. However, the Crusaders became frustrated with the Byzantines. For example, the Byzantines made a deal to take Nicaea from the Seljuks. This happened while the Crusaders were still attacking it. The Crusaders had hoped to take money and goods from Nicaea to pay for their journey.

The Crusaders felt betrayed by Alexios. He was able to get back many important cities and islands in western Asia Minor. The Crusaders continued their journey without Byzantine help. In 1098, Antioch was captured after a long attack. Then, the Crusaders themselves were trapped inside the city.

Alexios marched to meet them. But he heard from Stephen of Blois that the situation was hopeless. So, he went back to Constantinople. The Crusaders, who surprisingly survived the attack, believed Alexios had abandoned them. They thought the Byzantines could not be trusted. Because of this, they felt their oaths were no longer valid.

By 1100, several Crusader states had been formed. One was the Principality of Antioch, started by Bohemond in 1098. Some argued that Antioch should be returned to the Byzantines. But Bohemond claimed it for himself.

Alexios disagreed strongly. Antioch was an important port and a trade center with Asia. It was also a key place for the Eastern Orthodox Church. It had an important Eastern Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch. The Empire had only lost Antioch a few decades earlier. Alexios believed it should be returned to the Empire. This was based on the oaths Bohemond had sworn in 1097. So, Alexios tried to remove Bohemond from Antioch.

Bohemond further angered Alexios and the Eastern Orthodox Church in 1100. He appointed Bernard of Valence as the Latin Christian leader. At the same time, he forced out the Greek leader, John the Oxite. John fled to Constantinople.

Soon after, Bohemond was captured by the Danishmends of Syria. He was held prisoner for three years. During this time, the people of Antioch chose his nephew Tancred to rule for him. After Bohemond was freed, he was defeated by the Seljuks at the Battle of Harran in 1104. This loss put more pressure on Antioch from both the Seljuks and the Byzantines.

Bohemond left Tancred in charge of Antioch. He went back to the West, visiting Italy and France for more soldiers. He got support from Pope Paschal II and the French King Philip I. He even married the king's daughter.

Bohemond's Norman relatives in Sicily had been fighting the Byzantine Empire for over 30 years. His father, Robert Guiscard, was one of the Empire's biggest enemies. While Bohemond was away, Alexios sent an army to take back Antioch and the cities of Cilicia.

In 1107, Bohemond had gathered a new army. He planned to lead a crusade against the Muslims in Syria. Instead, he started a war against Alexios. He crossed the Adriatic Sea to attack Dyrrhachium. This was the westernmost city of the Empire.

However, like his father, Bohemond could not get far into the Empire. Alexios avoided a direct battle. Bohemond's attack failed, partly because a disease spread among his soldiers. Bohemond soon found himself trapped in front of Dyrrhachium. The Venetians blocked his escape by sea. Pope Paschal II also stopped supporting him.

What the Treaty Said

In September 1108, Alexios asked Bohemond to meet him. The meeting took place at the imperial camp in Diabolis (Devol). Bohemond had no choice but to agree. His sick army could no longer defeat Alexios in battle.

Bohemond admitted he had broken the oath he swore in 1097. But he argued it didn't matter now. He felt Alexios had also broken their agreement by turning back from the siege of Antioch in 1098. Alexios agreed to consider the 1097 oaths invalid.

The specific terms of the treaty were discussed by the general Nikephoros Bryennios. They were written down by Anna Komnene:

- Bohemond agreed to become a loyal follower of the Emperor. He also agreed to serve Alexios' son and heir, John.

- He promised to help defend the Empire whenever needed. He also agreed to an annual payment of 200 talents for this service.

- He was given the title of sebastos, and also doux (duke) of Antioch.

- He was given Antioch and Aleppo as imperial lands. (Neither the Crusaders nor the Byzantines controlled Aleppo yet. But it was understood Bohemond should try to conquer it.)

- He agreed to return Laodicea and other areas in Cilicia to Alexios.

- He agreed to let Alexios appoint a Greek Christian leader for Antioch. This showed Antioch's submission to the Empire.

The terms were set up based on Bohemond's Western understanding. He saw himself as a feudal follower of Alexios. This meant he had all the duties of a "liege man" (a loyal subject). He had to provide military help to the Emperor. He also had to serve him against all enemies, in Europe and Asia.

Anna Komnene wrote about these events in great detail. She described Bohemond often admitting his mistakes and praising Alexios. This must have been very embarrassing for Bohemond. However, Anna's writings were meant to praise her father. So, the treaty terms might not be completely accurate.

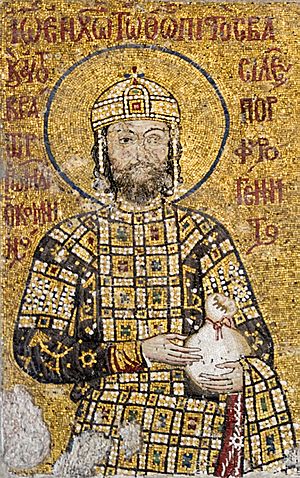

| "I promise you, our powerful and holy Emperor, Alexios Komnenos, and your co-Emperor, the much-loved John Porphyrogenitos, that I will follow all the conditions I have agreed to. I will keep them forever. I will always care for what is good for your Empire. I will never have any hateful or disloyal thoughts towards you... and I will always think of and do what benefits and honors the Roman rule. May God, the Cross, and the holy Gospels help me." |

| This was the promise made by Bohemond at the end of the Treaty of Devol, as written by Anna Komnene. |

The agreement was written down in two copies. One went to Alexios, and the other to Bohemond. Many important people from both sides witnessed the signing. This included church leaders, monks, and soldiers from Bohemond's side. From Alexios' court, there were high-ranking officials and ambassadors. Many of Alexios' witnesses were Westerners who held important positions in the Byzantine army.

Neither copy of the treaty still exists today. It might have been written in Latin, Greek, or both. It is not clear how much Bohemond's promises were known across Western Europe. Only a few writers even mention the treaty.

What Happened Next

Bohemond never went back to Antioch. He died in Sicily in 1111. The terms of the treaty were never put into action. Bohemond's nephew, Tancred, refused to follow the treaty.

The question of Antioch's status caused problems for the Empire for many years. Even though the Treaty of Deabolis never fully happened, it was the legal reason for Byzantine talks with the Crusaders for the next thirty years. It also supported the Empire's claims to Antioch during the reigns of John II and Manuel I.

So, John II tried to take control. He traveled to Antioch in 1137 with his army and attacked the city. The people of Antioch tried to talk, but John demanded they surrender completely. After getting permission from the King of Jerusalem, Fulk, Raymond, the Prince of Antioch, agreed to give the city to John.

This agreement, where Raymond promised loyalty to John, was based on the Treaty of Deabolis. But it went further. Raymond was recognized as an imperial follower for Antioch. He promised the Emperor free entry to Antioch. He also agreed to hand over the city. In return, he would get control of Aleppo, Shaizar, Homs, and Hama once they were taken from the Muslims. Then, Raymond would rule these new lands, and Antioch would go back to direct imperial rule.

However, the campaign failed. This was partly because Raymond and Joscelin II, Count of Edessa, who were supposed to help John, did not do their part. When they returned to Antioch, John insisted on taking control of the city. The two princes organized a riot. John found himself trapped in the city. He was forced to leave in 1138 and return to Constantinople. He politely accepted Raymond's and Joscelin's claims that they had nothing to do with the rebellion. John tried again in 1142, but he died unexpectedly. The Byzantine army then left.

It was not until 1158, during the rule of Manuel I, that Antioch truly became a follower of the Empire. This happened after Manuel forced Prince Raynald of Châtillon to promise fealty to him. This was a punishment for Raynald's attack on Byzantine Cyprus. The Greek Christian leader was brought back. He ruled at the same time as the Latin Christian leader. Antioch remained a Byzantine follower state until 1182. At that time, problems within the Empire after Manuel's death in 1180 made it hard for them to enforce their claim.

On the Balkan border, the Treaty of Deabolis marked the end of the Norman threat to the southern Adriatic Sea during Alexios' rule and later. The strong border defenses stopped any more invasions through Dyrrachium for most of the 12th century.