Crusader states facts for kids

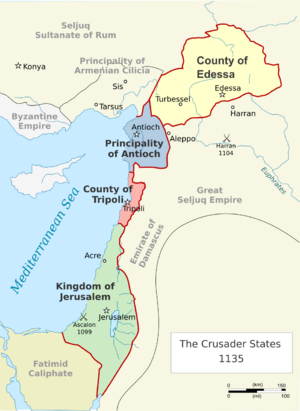

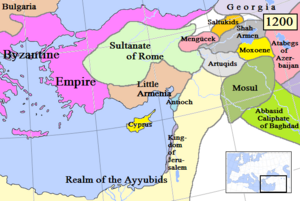

The Crusader states, also known as Outremer, were four Catholic kingdoms and counties in the Middle East. They existed from 1098 to 1291. These states were like small kingdoms based on the feudal system. They were set up by Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade through fighting and clever politics.

The four main states were:

- The County of Edessa (1098–1150)

- The Principality of Antioch (1098–1287)

- The County of Tripoli (1102–1289)

- The Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291)

The Kingdom of Jerusalem covered areas like modern Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip. The northern states were along the coasts of what are now Syria, southeastern Turkey, and Lebanon. The name "Crusader states" can be a bit confusing because after 1130, very few of the European settlers were actually crusaders. The term "Outremer" comes from French and means overseas.

In 1098, the crusaders, who were on an armed journey to Jerusalem, passed through Syria. Baldwin of Boulogne took over Edessa. Bohemond of Taranto became the ruler of Antioch after it was captured. In 1099, Jerusalem was taken after a siege. More land was gained, including Tripoli. At their largest, these states covered coastal areas of modern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Palestine.

Edessa fell to a Turkish leader in 1144. But the other states lasted into the 13th century. They eventually fell to the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Antioch was captured in 1268, and Tripoli in 1289. When Acre, the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, fell in 1291, the last lands were quickly lost. The survivors escaped to the Kingdom of Cyprus.

Historians started studying the Crusader states on their own, not just as part of the Crusades, in the 1800s. They saw them as a minority society, mostly living in cities. These Europeans, known as the Franks, were often separate from the local people. The local people included Christians and Muslims who spoke Arabic, Greek, and Syriac.

Contents

What were the Crusader States?

The terms Crusader states and Outremer (meaning overseas in French) describe the four feudal states created after the First Crusade. They were set up in the Levant (the eastern Mediterranean region) around 1100. From north to south, they were:

- The County of Edessa

- The Principality of Antioch

- The County of Tripoli

- The Kingdom of Jerusalem

"Outremer" is an old term from the Middle Ages. Modern historians use "Crusader states" and call the European newcomers "Franks". Most Europeans who came did not actually take a crusader oath. Medieval writings called all Western Christians from Europe Franci, no matter where they were from. This showed that the settlers were different from the local people in language and faith. The Franks mostly spoke French and were Roman Catholics. The locals were mostly Arabic- or Greek-speaking Muslims, Christians of other groups, and Jews.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem covered historical Palestine. At its largest, it included some land east of the Jordan River. The northern states covered parts of modern Syria, southeastern Turkey, and Lebanon. These areas were historically called Syria and Upper Mesopotamia. Edessa even stretched east beyond the Euphrates river.

Jerusalem was known as the Holy Land. Jews, Christians, and Muslims all considered it a very sacred place. It was linked to the lives of prophets, Jesus, and Muhammad. Holy places became shrines that pilgrims visited. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem marks where Christians believe Jesus was crucified and resurrected. The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem is thought to be his birthplace. The Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem are important for Muslims.

How the States Began

Europe Before the Crusades

Most crusaders came from what used to be the Carolingian Empire. This empire had broken apart into two main areas: the Holy Roman Empire (Germany and northern Italy) and France. France was even less united, with kings controlling only a small central area. Powerful counts and dukes ruled other regions.

Europeans and Muslims mostly met through war or trade. In earlier centuries, Muslims were stronger in war and trade. Europe was mostly rural and less developed. It offered raw materials and slaves for spices and luxuries from the Middle East. Later, climate change helped farming in Western Europe. This led to more people, more trade, and new wealthy groups.

In Catholic Europe, society was based on feudalism. Land was given in exchange for services, usually military help. Knights became a new class of mounted warriors. They built castles and fought often. This period also saw peasants becoming serfs, tied to the land. As land could be gained through conquest, European nobles were keen to fight for new territories.

The Papacy (the Pope's office) was very powerful. Popes could excommunicate opponents (kick them out of the church) and promise spiritual rewards for those who fought for their cause. In 1074, Pope Gregory VII even thought about leading a military campaign against the Turks.

The Middle East Before the Crusades

From the 800s, Turkic people moved into the Middle East. Some became slave soldiers called mamluks. These soldiers were very loyal to their masters. Eventually, some Mamluks became powerful leaders.

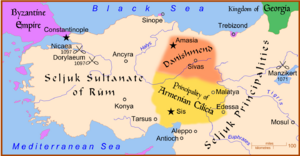

In the mid-1000s, a small group of Oghuz Turks called the Seljuks expanded their empire. Their leader, Tughril, was given the title of sultan (meaning 'power') by the Abbasid Caliph. The Seljuks were very violent and brought a nomadic lifestyle to the settled areas of the Levant. Their empire was large and diverse.

The Seljuk state could break apart when leaders fought among themselves. This happened often. The region was also very diverse in terms of people and religions. In Syria, Sunni Seljuks ruled over local Shias. There were also many Armenians, Byzantines, and Arabs. In Palestine, the Seljuks fought with Egypt, which was ruled by Shia leaders. The Seljuks and the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt hated each other because of old religious differences within Islam.

Islamic law allowed Christians and Jews, known as dhimmi, to practice their religion. They were second-class citizens and had to pay a special tax, but they could keep their own laws. Before the Muslim conquest, there were many different Christian groups in the Levant.

In 1071, the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan defeated the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at Manzikert. This weakened Byzantine control. Many Turkic groups moved into Anatolia. Suleiman ibn Qutulmish took Cilicia and Antioch in 1084. Later, many important leaders died, leading to more fighting and chaos among Muslim rulers.

The Seljuk invasions and the weakening of the Byzantines and Fatimids led to the rise of independent city-states in the Levant. Local leaders, whether Turkic, Arab, or Armenian, took control of cities like Tyre, Tripoli, Shaizar, Damascus, Aleppo, Antioch, and Edessa. During this time, Muslim leaders often fought each other more than they fought Christians.

The First Crusades and New States

Starting the Crusader States

The Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos asked Pope Urban II for help against the Seljuks in 1095. Urban II called for the First Crusade, which was an armed journey to free Eastern Christians and take back the Holy Land. Thousands of people, both commoners and nobles, joined. Some probably wanted to make a new home in the Levant.

Alexios was careful with the European armies. He made most Crusader leaders promise to return any land they gained that used to belong to the Byzantine Empire. These leaders included Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohemond of Taranto, and Baldwin of Bologne. Only Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse refused this oath.

Baldwin and his men left the main army and went to the Euphrates river. They took over areas where Armenians welcomed them. Thoros, the ruler of Edessa, adopted Baldwin as his son. In March 1098, a Christian crowd killed Thoros and made Baldwin their leader. This was the start of the County of Edessa.

At Antioch, Bohemond convinced other leaders that if he captured the city, it should be his. In June 1098, crusaders entered Antioch and killed many Muslim inhabitants. Bohemond claimed the city for himself, creating the Principality of Antioch.

The crusaders then marched to Jerusalem. On July 15, 1099, they captured the city after a siege. Thousands of Muslims and Jews were killed or sold into slavery. Godfrey of Bouillon was proclaimed the first Frankish ruler of Jerusalem. He took the title Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri ('Defender of the Holy Sepulchre'). This meant he was responsible for protecting the church's lands.

The creation of these three states didn't completely change the region. European rulers replaced local leaders, but there wasn't a huge wave of European settlers. The new rulers didn't change how land and property were organized in the countryside. Treaties between Christians and Muslims were common. Frankish knights often saw Turkic leaders as equals. Conquering a city often led to a treaty where neighboring Muslim rulers paid tribute for peace.

Building Up the States (1099 to 1130)

For over ten years, the Fatimids and Seljuks fought each other, which helped the Franks. The Franks were outnumbered but made temporary alliances with their Armenian, Arab, and Turkic neighbors. Each Crusader state had its own goals. Jerusalem needed access to the sea. Antioch wanted to control Cilicia and the Orontes River area. Edessa wanted the Upper Euphrates valley.

In 1100, Godfrey of Bouillon died. His brother Baldwin became Jerusalem's first Latin king on Christmas Day 1100. This meant the Patriarch (church leader) gave up his claim to rule the Holy Land.

Baldwin I fought off attacks from the Fatimid Caliphate and, with help from Italian and Norwegian fleets, conquered all the towns on the Palestinian coast except Tyre and Ascalon.

Raymond of Toulouse started the fourth Crusader state, the County of Tripoli. He captured Tartus and Gibelet and besieged Tripoli. After his death in 1105, his cousin and then his son continued the siege. Tripoli was captured in 1109.

The fall of Tripoli made the Seljuk Sultan send armies to fight the Franks. But Muslim leaders in Syria saw this as a threat to their own power and sometimes worked with the Franks.

In 1118, Baldwin I died. Baldwin of Bourcq became King of Jerusalem. He named his cousin Joscelin of Courtenay as his successor in Edessa.

A new idea came from a group of religious knights: a monastic order for warriors. This led to the creation of two important military orders: the Knights Templar and the Hospitallers. These groups of armed monks played a huge role in defending the Crusader states.

Baldwin II had four daughters. His eldest daughter, Melisende, was his heir. He married her to Fulk of Anjou, who had many connections in Europe. After Fulk arrived, Baldwin tried to attack Damascus, but the campaign failed. In 1130, Bohemond II was killed, leaving his infant daughter, Constance. Baldwin II became regent of Antioch until his death in 1131.

Muslim Power Grows (1131 to 1174)

After Baldwin II died, Fulk, Melisende, and their young son Baldwin III were joint heirs. Fulk tried to rule alone, but this caused problems. He had to accept shared rule. He also stopped his sister-in-law, Alice, from taking control in Antioch.

Imad al-Din Zengi, a powerful Muslim leader, captured Aleppo in 1128. This union of two major Muslim cities was dangerous for Edessa and Damascus.

In 1144, Zengi invaded the Frankish lands east of the Euphrates and captured Edessa. This was a big blow to the Franks. Losing Edessa threatened Antioch and limited Jerusalem's expansion. In 1146, Zengi was killed. His empire was divided between his sons. Nur ad-Din took Aleppo. Joscelin tried to take Edessa back, but Nur ad-Din arrived and sacked the city.

The fall of Edessa shocked Europe. This led to the Second Crusade, with large armies led by Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. They arrived in Acre in 1148. They decided to attack Damascus instead of trying to get Edessa back. But the attack on Damascus failed badly. Fewer crusaders came from Europe after this.

Nur ad-Din continued to gain power. He invaded Antioch, and its leader, Raymond of Poitiers, was defeated and killed in 1149. The next year, Joscelin was captured and later died. The remaining parts of the County of Edessa were sold to the Byzantines.

Baldwin III became king alone in 1152. In Antioch, Constance married Raynald of Châtillon. Baldwin captured Ascalon in 1153, the last Fatimid stronghold in Palestine. But Nur ad-Din easily took Damascus a year later.

Baldwin III died in 1163. His brother Amalric became king. He launched five invasions of Egypt between 1163 and 1169, sometimes with Byzantine help, but couldn't establish control. Nur ad-Din sent his general Shirkuh to Egypt. Shirkuh's nephew Saladin later took over. Saladin ended the Shia caliphate in Egypt in 1171. In theory, Saladin was Nur ad-Din's lieutenant, but they didn't trust each other. Nur ad-Din died in 1174, leaving a young son. Within two months, Amalric also died. His son, Baldwin IV, was 13 and had leprosy.

Decline and Survival (1174 to 1188)

With young rulers in Jerusalem and Muslim Syria, there was a lot of disunity. In Jerusalem, Raymond III, Count of Tripoli, became regent for Baldwin IV. He became very powerful. Nur ad-Din's empire quickly broke apart. Saladin reunited much of Muslim Syria by fighting against other Muslim leaders.

Raymond tried to keep a balance of power in Syria. He even signed a truce with Saladin. Raynald of Châtillon and Joscelin III of Courtenay were released for a large ransom. Raynald gained Oultrejourdain by marriage.

Baldwin IV had leprosy and was not expected to have children. His sister Sibylla was his heir. Raymond chose William of Montferrat as her husband. In 1176, Baldwin became king on his own. He planned an invasion of Egypt and renewed his alliance with the Byzantines. But the plan was abandoned.

Tension grew between Baldwin's relatives. To stop a possible coup, Baldwin quickly married Sibylla to Guy of Lusignan, a young nobleman. Guy's family had strong ties to the English royal family.

Saladin made truces with Baldwin and Raymond to prepare for a campaign against the Seljuks. For the first time, the Franks couldn't set the terms for peace. Saladin gained control of Cairo and Damascus. Raynald attacked an Egyptian caravan, breaking the truce. This made Saladin prepare for a holy war.

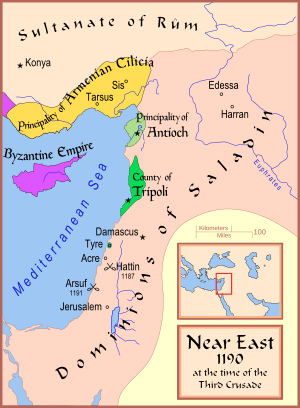

In July 1187, Saladin's troops defeated the Frankish army at the Horns of Hattin. This was a huge defeat for the Franks. Most of their leaders were captured. Only Raynald and the armed monks of the military orders were executed. Raymond was one of the few who escaped. Within months, Saladin conquered almost the entire kingdom. Jerusalem surrendered on October 2, 1187. There were no massacres, but thousands of Franks were enslaved. Survivors fled to Tyre, Tripoli, or Antioch. Conrad of Montferrat defended Tyre.

News of the defeat at Hattin reached Europe, leading to the Third Crusade. Many people took the crusader oath. Saladin tried to besiege Tyre but failed. He released Guy of Lusignan, hoping it would cause problems among the Franks. Guy failed to leave for Europe. In October, Bohemond asked Saladin for a truce. By 1188, Saladin had conquered almost all Frankish lands except Tyre and parts of Antioch and Tripoli.

Recovery and Civil War (1189 to 1243)

Guy of Lusignan and his allies gathered forces and attacked Acre in August 1189. Crusaders from all over Europe joined them. This surprised Saladin. Three major Crusader armies arrived in 1189–1190. Frederick Barbarossa drowned, and only parts of his army reached the Holy Land. Philip II of France arrived in April 1191, and Richard I of England in May. Richard had captured Cyprus on his way.

Acre surrendered after a long siege. Philip and most of the French army returned home. Richard led the crusaders to victory at Arsuf, capturing Jaffa and other towns. Guy and Conrad had fought over who should be king. When Guy's wife Sibylla died, Conrad married Isabella, Sibylla's half-sister and heir. Richard eventually accepted Conrad as king and gave Guy Cyprus as compensation. In April 1192, Conrad was killed. Isabella then married Henry, Count of Champagne.

Saladin and Richard agreed to a three-year truce in September 1192. The Franks kept the land between Tyre and Jaffa. Christian pilgrims could visit Jerusalem. The Franks' position was not bad: they held coastal towns and their borders were shorter. After Saladin died in March 1193, his sons fought among themselves. The Ayyubids (Saladin's family) often made truces with the Franks and gave up land to keep the peace.

The ruler of Antioch, Bohemond III, had problems with his Armenian vassal Leo. Leo captured Bohemond in 1194, demanding Antioch for his release. Bohemond was released when he gave up his claims on Cilicia and arranged a marriage between his son Raymond and Leo's niece Alice. This was meant to unite Antioch and Armenia. But Raymond died, and the War of the Antiochene Succession began, lasting over ten years.

The leaders of the Fourth Crusade planned to invade Egypt but instead sacked Constantinople in 1204. Isabella of Jerusalem died in 1205. Her daughter Maria became queen, and John of Ibelin became regent. Maria married John of Brienne in 1210. After her death, John ruled as regent for their daughter, Isabella II.

The Fifth Crusade invaded Egypt and captured Damietta in 1219. The Sultan of Egypt offered to return Jerusalem and the Holy Land for their withdrawal. But the crusaders refused and marched on Cairo. They were trapped and had to surrender Damietta, ending the crusade.

Frederick II, the ruler of Germany and Sicily, married Isabella II in 1225 and became King of Jerusalem. He sailed for the Sixth Crusade in 1228, even though the Pope had excommunicated him. Frederick made a truce with the Sultan. It returned Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, and Sidon to the Franks. However, the Temple Mount in Jerusalem remained Muslim. The local Franks were not happy with this treaty.

Frederick left for Italy in 1229 and never returned. He sent Richard Filangieri to rule Jerusalem. But the local nobles, led by the Ibelin family, disagreed. This led to a civil war called the War of the Lombards. The Ibelins took Acre and set up a commune to protect their interests.

New crusades came from Europe between 1239 and 1241. They used diplomacy to gain more land for the Franks. By 1243, most land west of the Jordan River was back in Frankish hands.

End of the Crusader States (1244 to 1291)

The Mongol Empire expanded westward. Some of their soldiers, the Khwarazmians, offered their services to local rulers. In July 1244, Khwarazmians sacked Jerusalem. The Franks joined forces with the Damascenes, but they were defeated at La Forbie on October 18. Few Franks survived. Most of the crusaders' land was lost, leaving them with only a few coastal towns.

Louis IX of France launched a failed crusade against Egypt in 1249. He was captured and later ransomed. Louis spent four more years in the Holy Land, strengthening coastal towns.

Fighting between Venice and Genoa led to a new civil war in 1256. In 1258, the Mongols sacked Baghdad. In 1260, Hethum I of Cilicia and Bohemond VI joined the Mongols in attacking Aleppo and northern Syria. The Mongols treated Christians better, and local Christians cooperated with them.

The Mamluks of Egypt defeated the Mongols at Ain Jalut. The Mamluk sultan Baibars reunited Egypt and Syria. The Franks were too weak to resist. Baibars captured Caesarea and Arsuf in 1265, Safed in 1266, and sacked Antioch in 1268. He also captured important castles like Krak des Chevaliers. When the Mamluks conquered a city, they often killed or enslaved the Franks and local Christians.

In 1277, Charles I of Anjou claimed the title of King of Jerusalem. He sent a representative to rule, but the local nobles resisted. The Mongols tried to form alliances with European rulers against the Mamluks, but without much success.

In 1289, the Mamluk sultan Al-Mansur Qalawun destroyed Tripoli. In 1290, Italian crusaders broke a truce by killing Muslim traders in Acre. This led to the Mamluk siege of Acre in 1291. The city fell, and those who could fled to Cyprus. Others were killed or enslaved. Without hope of help from Europe, Tyre, Beirut, and Sidon surrendered. The Mamluks destroyed the ports and fortified towns to remove all signs of the Franks.

How the States Were Run

Modern historians have studied the Kingdom of Jerusalem the most. Its royal government was based in Jerusalem, and later in Acre. It had officers like a constable, marshal, and chamberlain, similar to European rulers. Local areas were managed by Viscounts. All written laws were lost when Jerusalem fell in 1187. The courts of Antioch had similar laws, which were later used in Cilician Armenia.

The people in Antioch were a mix of Franks, Syrians, Greeks, Jews, Armenians, and Muslims. They generally got along well. Edessa is less studied because it was landlocked and didn't last long. Its government was similar to northern French systems. Tripoli was ruled by Raymond of Saint-Gilles and his successors. They granted land to lords from France.

The King of Jerusalem was mainly the leader of the army. Early kings had more power than European monarchs because they controlled more land directly. They rewarded loyal followers with city incomes.

Later, powerful nobles like Raynald of Châtillon and Raymond III of Tripoli became very independent. The central government's power decreased. Decisions were made in the High Court, or Haute Cour. This court included the king and his most important vassals. By the end of the 1100s, leaders of the military orders and Italian merchant groups also joined.

After the defeat at Hattin in 1187, the Franks lost their cities and lands. Many nobles fled to Cyprus. The kings of Jerusalem were often absent, ruling from Europe. The central government collapsed, and nobles, military orders, and Italian merchant groups became very independent.

Military Power

Army Size and Recruitment

It's hard to know exactly how big the Frankish and Muslim armies were. But it seems the Franks of Outremer could raise some of the largest armies in the Catholic world. For example, in 1111, the four Crusader states together had 16,000 troops for a campaign. Edessa and Tripoli had 1,000–3,000 troops, while Antioch and Jerusalem had 4,000–6,000.

In comparison, William the Conqueror had 5,000–7,000 troops at Battle of Hastings. The Fatimids had 10,000–12,000 troops, and Aleppo had 7,000–8,000. Saladin, after uniting Egypt and Syria, could raise armies of about 20,000. The Franks increased their forces to about 18,000 in response.

The Crusader states' military strength came from four main groups:

- Vassals: Nobles who owed military service to their lord.

- Mercenaries: Hired soldiers, very important for campaigns and guarding forts.

- Visitors from the West: Armed pilgrims who came to help.

- Military Orders: Professional soldiers like the Templars and Hospitallers.

Military Orders

Military orders were a new type of religious group created because of the unstable conditions. The first was the Knights Templar. Around 1119, these knights took monastic vows (like monks) and promised to protect pilgrims visiting Jerusalem. This idea of armed monks was unusual but gained support. Their rules were approved in 1129. They were named after Solomon's Temple (the Frankish name for the Al-Aqsa Mosque), where they had their first base.

The Hospitallers were another early example. They started as a group helping at a hospital in Jerusalem. In the 1130s, they also became soldiers. Other military orders followed, like the German Order of Teutonic Knights and the English Knights of Saint Thomas.

These orders became very wealthy from donations across Europe. They managed their lands through a network of branch houses. They also acted like early banks, helping with money transfers and loans. The Hospitallers continued their charitable work, running a hospital that served hundreds of patients of all religions.

But their main duty was fighting against non-Christians. They were like a standing army and were vital for defending the Crusader states. Their knight-brothers and servants were professional soldiers under religious vows. They wore special uniforms with a cross. Since rulers often lacked money for defense, they gave their border forts to the military orders. Examples include Beth Gibelin and Krak des Chevaliers.

Fighting Styles and Weaknesses

Frankish armies relied on highly trained mounted knights. Their skill and teamwork made them stand out. Frankish foot soldiers worked closely with the knights, protecting them from attacks by Turkic light cavalry. The Franks also used many foot soldiers with crossbows. Native Christians and converted Turks, called turcopoles, served as lightly armored cavalry for raids.

Frankish knights fought in tight groups, using cavalry charges. Muslims tried to avoid direct clashes until the knights were tired. Frankish foot soldiers could form a "shield-roof" against arrows. Both sides used fake retreats, though Christians thought it was shameful. In sieges, Franks preferred blockades to starve defenders. Muslims preferred direct attacks. Both sides used similar siege engines like towers and rams. Muslims used carrier pigeons and signal fires to get information quickly.

A major defeat could threaten a Crusader state because the Franks couldn't replace lost soldiers as easily as their enemies. After the 1150s, some observers thought the Franks' military skills had weakened. However, historians now think their defeats were more due to their enemies' improved tactics. Muslims learned to overcome their own weaknesses and exploit Frankish ones. They used jihad (holy war) propaganda to unite their forces. The Franks, however, struggled with disagreements among their own commanders.

People and Society

It's hard to know the exact population numbers for the Crusader states. Estimates for Franks range from 120,000 to 300,000. If true, Franks made up at least 15% of the total population.

People continued to move from Catholic Europe to the Crusader states. Most settled in coastal cities, but Franks also lived in over 200 villages in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Some villages were planned for Western settlers. Native Christians often shared villages with Franks. After lands were lost to Muslims, many Christian refugees moved to coastal cities.

Historians believe that Muslims and local Christians were not as integrated with the Franks as once thought. Christians lived around Jerusalem and in other areas. Maronites were in Tripoli, and Jacobites in Antioch and Edessa. Armenians were mostly in the north. Central areas had mostly Sunni Muslims, but Shia communities were in Galilee. Druze lived in the mountains of Tripoli. Jews lived in coastal towns and some villages.

Most local people were peasants who worked the land. They were tied to the land but had more rights than serfs in Europe. They could marry outside their lord's land and own property. They had to pay a part of their crops and a special tax.

Language was a big difference. Franks usually spoke Old French and wrote in Latin. Few learned Arabic, Greek, Armenian, Syriac, or Hebrew. Society was divided by politics and law. Different ethnic groups governed themselves, with the Franks controlling relations between them.

In towns, local leaders called ruʾasāʾ managed Frankish estates and governed native communities. Courts for native communities handled civil disputes. Frankish courts dealt with more serious crimes and cases involving Franks. It's hard to know how much cultures mixed. Some historians think the different groups led to less formal separation.

Frankish royalty reflected the region's diversity. Queen Melisende was partly Armenian. Her son Amalric married a Byzantine Greek. Frankish nobles used Jewish, Syrian, and Muslim doctors. Antioch became a place where Greek- and Arabic-speaking Christians exchanged ideas. Local people showed respect to Frankish nobles, and Franks sometimes adopted local clothes, food, and military methods. However, Frankish society was not a "melting pot." People kept their separate identities.

Economy and Trade

The Crusader states were important trade centers. They connected Europe with the Middle East. Many Eastern goods were sent to Europe. European populations and economies were growing, creating a demand for goods from the East. European ships improved, and pilgrims helped pay for voyages.

Before Saladin's conquests in 1187, farming was important. After that, it became less so. Franks, Muslims, Jews, and local Christians traded goods in the city markets, called souks.

Olives, grapes, wheat, and barley were key farm products. Glass making and soap production were big industries in towns. Italians, French, and Catalans controlled shipping, imports, exports, and banking. Frankish nobles and the church earned money from taxes on trade, markets, pilgrims, and industries. Landowners had monopolies on mills and ovens, forcing people to use them.

Antioch, Tripoli, Tyre, and Beirut were major production centers. Textiles (especially silk), glass, dyes, olives, wine, sesame oil, and sugar were exported. The Franks imported clothing and finished goods. They used a mix of European, Arabic, and Byzantine coins. After 1124, the Franks copied Egyptian gold coins, creating Jerusalem's gold bezant. After 1187, trade became more important than farming, and European coins were more common.

Italian merchant cities like Pisa, Venice, and Genoa were strong supporters of the crusades. Their wealth gave the Franks financial help and naval power. In return, these cities got special trade rights and access to Eastern markets. They set up their own communities in ports like Acre, Tyre, Tripoli, and Sidon. These communities had their own cultures and political power, separate from the Franks. They controlled foreign trade, banking, and shipping. For example, in 1124, the Venetians received one-third of Tyre and tax exemptions for helping in the siege. By the mid-1200s, these Italian communities had so much power that they divided Acre into several fortified "republics."

Art and Buildings

Historians believe that the military buildings of the Crusader states show a mix of European, Byzantine, and Muslim styles. This made them unique and impressive. Castles were a sign of the Franks' power over the local population. They also served as administrative centers.

Modern historians now think that Europeans already had advanced defensive building skills before coming to the Near East. But contact with Arab fortifications, which were originally built by Byzantines, did influence designs in the East. Castles sometimes included Eastern features like large water reservoirs.

Churches were built in the French Romanesque style. The rebuilding of the Holy Sepulchre in the 1100s kept some older Byzantine details but added French arches and chapels.

Art and visual culture show how different cultures mixed. Shrines, paintings, and manuscripts were decorated by local artists. Frankish artists learned from Byzantine and local artists. Wall mosaics, which were not common in the West, were widespread in the Crusader states. This shows a unique artistic style developing. Workshops had Italian, French, English, and local craftsmen working together, creating illustrated manuscripts like the Melisende Psalter.

Religion

There is little written proof that Franks and local Christians saw major religious differences until the 1200s. When Greek Orthodox church leaders died, Franks sometimes took their places. For example, Arnulf of Chocques became the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem. This didn't affect Arabic-speaking Orthodox Christians much, as their previous bishops were often foreign Byzantines.

Armenians, Copts, Jacobites, Nestorians, and Maronites had more religious freedom. They could appoint their own bishops. The Franks had laws that discriminated against Jews and Muslims, preventing them from fully mixing into society. Their legal status was a Frankish version of the dhimmi system.

Jews and Muslims kept their own religious laws. They faced discrimination in civil law and had to pay a special tax. Muslims were often kept out of town life. However, Muslim villagers under Crusader rule seemed to do as well as, or even better than, those in Muslim lands. Some mosques were turned into Christian churches, but most stayed Muslim. Muslims could sometimes pray in parts of former mosques. There was no forced conversion of Muslims, as this would mean losing their peasant status. Crusaders generally weren't interested in converting Jews, Muslims, or other Christian groups to Latin Christianity.

What Lasted?

The Franks mostly followed the customs of their European homelands. So, they didn't create many lasting new things. But there were three important exceptions: the military orders, new ways of fighting, and castle building.

After Acre fell, the Hospitallers moved to Cyprus. Then they conquered and ruled Rhodes (1309–1522) and Malta (1530–1798). The Sovereign Military Order of Malta still exists today.

The Crusades led to more trade between Europe and the Crusader states. Italian cities like Genoa and Venice became rich through profitable trading communities. Many historians believe that the interaction between Western Christian and Islamic cultures had a big and positive influence on European civilization and the Renaissance. It's hard to say exactly how much cultural exchange came from the Crusader states compared to other places like Sicily and Spain.

See also

In Spanish: Estados cruzados para niños

In Spanish: Estados cruzados para niños