Battle of Arsuf facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Arsuf |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Crusade | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Angevin Empire Kingdom of France Kingdom of Jerusalem Knights Hospitaller Knights Templar Contingents from other states |

Ayyubid Sultanate | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Richard I, King of England Hugh III, Duke of Burgundy Guy of Lusignan Garnier de Nablus Robert IV of Sablé James of Avesnes † Henry II, Count of Champagne |

Saladin Saphadin Al-Afdal ibn Saladin Aladdin of Mosul Musek, Grand Emir of the Kurds † Al-Muzaffar Taqi al-Din Umar |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

11,200 (total)

|

25,000 cavalry | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| c. 700 killed (est.) (Itinerarium) | c. 7,000 killed (est.) (Itinerarium) | ||||||||

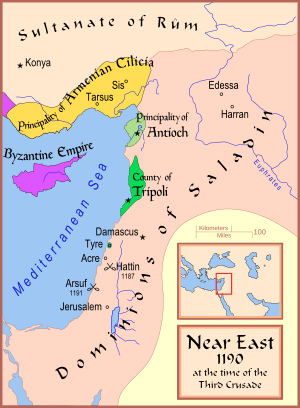

The Battle of Arsuf was a major fight during the Third Crusade. It happened on September 7, 1191. In this battle, a group of Crusaders from many different countries, led by Richard I of England (also known as Richard the Lionheart), fought against a much larger army. This larger army belonged to the Ayyubid Sultanate and was led by the famous Muslim leader Saladin.

The Crusaders had just captured the city of Acre. Richard wanted to take the port city of Jaffa next. Saladin tried to stop Richard's army as it marched along the coast. Saladin's forces launched many small attacks to try and break the Crusader army's formation. But the Crusaders stayed strong and kept their shape.

As the Crusaders moved across a plain near the city of Arsuf, Saladin decided to use his entire army in a big battle. Richard kept his army in a defensive formation, waiting for the perfect moment to strike back. However, some of his knights, the Knights Hospitaller, charged forward early. This forced Richard to send in his whole army to support them. The Crusader charge broke Saladin's army. Richard then cleverly stopped his cavalry from chasing too far, regrouped them, and secured a big victory.

After the battle, the Crusaders gained control of the central coast of Palestine, including the important city of Jaffa.

Getting Ready: Marching from Acre

After taking Acre in 1191, King Richard knew he needed to capture Jaffa. Jaffa was a port city that would be important for attacking Jerusalem. So, in August, Richard began marching his army south along the coast from Acre towards Jaffa.

Saladin's main goal was to prevent the Crusaders from taking Jerusalem back. He gathered his army to stop Richard's advance. Richard was very careful about how he organized his march. Many of Saladin's ships had been captured at Acre, so Richard's right side was safe from sea attacks. His own fleet sailed close by, providing supplies and a safe place for wounded soldiers.

Saladin had already destroyed Jaffa's walls in 1190. He did this to make sure the Crusaders couldn't use the city's strong defenses.

Richard's Smart Marching Plan

Richard remembered the terrible defeat at Hattin, where many Crusaders suffered from thirst and heat. He knew his army needed water and to avoid getting too hot. So, he marched slowly, only in the mornings before the heat became too strong. They often stopped to rest near water sources.

His army marched in a tight formation. In the middle were twelve groups of mounted knights. The foot soldiers marched on the land side, protecting the knights from enemy attacks. The outer rows of foot soldiers were crossbowmen, who could shoot far. On the side facing the sea, Richard kept the baggage and soldiers who were resting. He regularly switched out his foot soldiers to keep them fresh.

Saladin's archers constantly attacked the Crusaders. But Richard's leadership kept his army disciplined and in order. A Muslim writer named Baha al-Din described how powerful the Crusader crossbows were. He saw Frankish (Crusader) foot soldiers with many arrows stuck in their armor, but they kept marching. Meanwhile, the crossbows could kill both horses and men among the Muslims.

Saladin's Plan to Attack

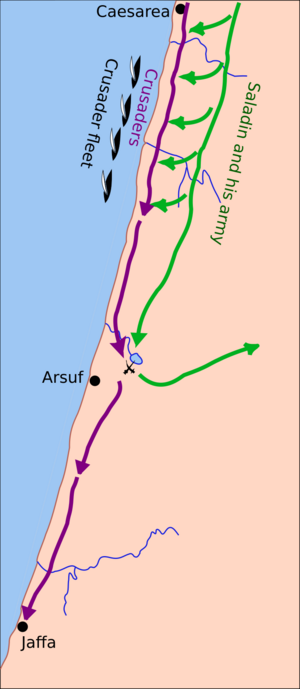

The Crusader army moved slowly because of their foot soldiers and supplies. Saladin's army, mostly made of horsemen, could move much faster. Saladin tried to burn crops to deny food to the Crusaders, but it didn't work well. Richard's army got all its supplies from the ships sailing alongside them.

On August 25, Saladin almost cut off the Crusader rearguard in a narrow pass. But the Crusaders quickly closed ranks, forcing the Muslim soldiers to retreat. From August 26 to 29, Richard's army had a break from attacks. They hugged the coast, while Saladin's army took a shortcut across the land. Saladin reached Caesarea before the Crusaders.

From August 30 to September 7, Saladin stayed close to the Crusaders. He was waiting for a chance to attack if they made a mistake. By early September, Saladin realized that small attacks wouldn't stop the Crusaders. He needed to use his whole army. Luckily for Saladin, the Crusaders had to march through the "Wood of Arsuf." This forest ran along the coast for over 20 kilometers. The trees would hide his army and allow for a surprise attack.

The Crusaders marched through half the forest without trouble. On September 6, they rested near a marsh. South of their camp, they had to march 10 kilometers to reach the ruins of Arsuf. Here, the forest moved inland, creating a narrow plain between the hills and the sea. This was where Saladin planned his big attack.

Saladin attacked along the entire Crusader column, but he focused his strongest attacks on the rear. His plan was to let the Crusader front and middle sections move ahead. He hoped this would create a gap between them and the heavily attacked rear. Saladin would then send his reserve troops into this gap to defeat the Crusaders piece by piece.

The Battle Begins

How Many Soldiers?

The Itinerarium Regis Ricardi, a historical account, says Saladin's army had three times as many soldiers as the Crusaders. However, the numbers given (300,000 for Saladin and 100,000 for Crusaders) are likely too high.

Modern historians believe Saladin's army had about 25,000 soldiers. Almost all of them were cavalry (horse archers, light cavalry, and some heavy cavalry). Richard's army likely had around 10,000 foot soldiers (including spearmen and crossbowmen) and 1,200 heavy cavalry. So, Saladin's army was probably about twice the size of Richard's.

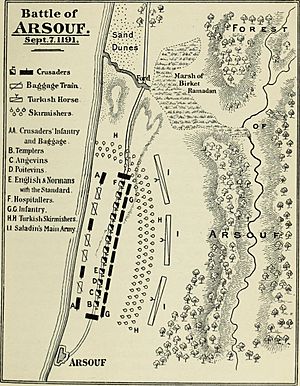

How the Armies Lined Up

At dawn on September 7, Richard's army started moving. Enemy scouts were everywhere, showing that Saladin's entire army was hidden in the forest. King Richard was very careful about how he arranged his army. He put the military orders, like the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, at the front and especially the rear. These were the most dangerous spots.

The military orders had the most experience fighting in the East. They were also the most disciplined. They even had Turcopole cavalry, who fought like the Turkish horse archers of Saladin's army.

The front of the Crusader army was led by the Knights Templar under Robert de Sablé. Then came three groups of Richard's own men: from Anjou, Brittany, and Poitou (including Guy of Lusignan, the King of Jerusalem). Finally, the English and Normans carried the main battle flag. After them were seven groups of French, Flemish, and local Crusader knights. The very back was guarded by the Knights Hospitaller, led by Garnier de Nablus.

Richard himself, along with Hugh of Burgundy (leader of the French), rode up and down the column. They watched Saladin's movements and made sure their own ranks stayed in order.

Saladin's army burst out of the woods only after all the Crusaders had left their camp. The front of Saladin's army was made of many skirmishers. These were horse and foot soldiers, Bedouin, Sudanese archers, and light Turkish horse archers. Behind them were the organized groups of armored heavy cavalry. These included Saladin's best soldiers, called mamluks, Kurdish troops, and soldiers from Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia. Saladin led his army from the center, surrounded by his guards and drummers.

Saladin's First Attacks

Saladin's attack began with a lot of noise. Cymbals clashed, gongs sounded, trumpets blew, and men screamed war-cries. This was meant to scare the Crusaders and break their formation.

The Ayyubid attacks followed a pattern:

- First, Bedouin and Nubian foot soldiers would shoot arrows and throw javelins.

- Then, they would move aside for the mounted archers to ride forward, shoot, and quickly turn away. This was a well-practiced tactic.

The Crusader crossbowmen shot back when they could. But their main job was to keep their ranks tight and not break formation, even with constant attacks. When these small attacks didn't work, Saladin focused his attack on the rear of the Crusader column. The Hospitallers at the back faced the most pressure. Many Hospitaller foot soldiers had to walk backward to keep their shields facing the enemy.

Saladin himself rode into the fight, urging his soldiers to get closer. His brother, Sayf al-Din, also encouraged the troops. Both brothers were in danger from Crusader crossbow fire.

Hospitallers Charge!

Even with all of Saladin's efforts, he couldn't break the Crusader column or stop its march towards Arsuf. Richard wanted to keep his army together. He wanted the enemy to tire themselves out with repeated charges. He planned to save his knights for one big counter-attack at the perfect moment. This was risky because his army was under constant attack and suffering from heat and thirst. Many Crusader horses were being killed, making some knights wonder if a counter-attack would even be possible. Many knights whose horses were killed joined the foot soldiers.

As the front of the Crusader army entered Arsuf in the afternoon, the Hospitaller crossbowmen at the rear were struggling. They had to load and shoot while walking backward. Their formation started to break, and the enemy quickly moved into the gaps with swords and maces. The Battle of Arsuf was at a critical point.

Garnier de Nablus, the Hospitaller leader, kept asking Richard for permission to attack. Richard refused, telling him to hold his position and wait for the signal: six clear trumpet blasts. Richard knew his knights' charge needed to wait until Saladin's army was fully committed, close to them, and their horses were tired.

However, the Hospitaller marshal and one of Richard's knights, Baldwin le Carron, charged into the Saracen ranks, shouting "St. George!" The rest of the Hospitaller knights followed them. Inspired by this, the French knights just ahead of the Hospitallers also charged.

Some historians believe the Hospitallers charged without Richard's direct order, out of frustration. Others suggest Richard might have given trusted leaders permission to act on their own if a good opportunity arose. It's also unclear if a trumpet signal could even be heard over the noise of the battle.

Crusader Counterattack

Whether it was a planned move or not, Richard knew he had to support the charge once it started. He ordered the signal for a general attack. If the Hospitallers had been left alone, Saladin's larger army would have crushed them. The Frankish foot soldiers opened gaps for the knights to ride through. The attack spread from the rear to the front.

To Saladin's soldiers, this sudden change from passive marching to fierce attacking was very confusing. It seemed like a planned move. Saladin's right wing, which had been fighting the Crusader rear, was in a tight group and too close to escape the charge. Some of their cavalry had even gotten off their horses to shoot arrows better. As a result, Saladin's army suffered huge losses. The knights took revenge for all the attacks they had endured.

Baha al-Din, a Muslim historian, wrote that "the rout was complete." He was in the center of Saladin's army and saw it flee. He looked for the left wing, but it was also running away. He found Saladin's personal banners, but only seventeen bodyguards and one drummer were left with them.

Richard knew that chasing too far was dangerous when fighting armies like the Turks, who used flexible tactics. So, he stopped the charge after about 1.5 kilometers. The Crusader units on the right flank (including the English and Normans), who had been at the front of the column, hadn't fought much up close yet. They formed a fresh reserve, and the rest of the army regrouped behind them.

Once the pressure of the chase was off, many of Saladin's troops turned back to fight knights who had ridden too far ahead. James of Avesnes, a French commander, was one of those killed. Among Saladin's leaders who quickly regrouped was Taqi al-Din, Saladin's nephew. He led 700 of the Sultan's personal guards against Richard's left side.

Once his squadrons were back in order, Richard led his knights in a second charge. Saladin's forces broke and ran again. Richard, always careful, stopped and regrouped his forces one more time after another chase. Saladin's cavalry turned again, showing they still wanted to fight. However, a third and final charge made them scatter into the woods and hills. They showed no desire to continue fighting. Richard led his cavalry back to Arsuf, where the foot soldiers had set up camp. During the night, the dead Saracen soldiers were looted.

What Happened Next

It's hard to know exactly how many people died in medieval battles. Christian writers claimed Saladin's army lost 32 leaders and 7,000 men, but the real number might have been lower. Ambroise, a Crusader writer, said Richard's troops counted thousands of dead Saracen soldiers after the battle. Baha al-Din only recorded three deaths among Saladin's leaders. King Richard's army is said to have lost no more than 700 men. The only important Crusader leader to die was James d'Avesnes, a French knight.

Arsuf was a very important victory. Saladin's army wasn't completely destroyed, but it did run away. This was seen as shameful by the Muslims and greatly boosted the Crusaders' spirits. Some people at the time thought that if Richard had been able to choose the exact moment for his knights to charge, the victory could have been even more complete. It might have stopped Saladin's forces for a long time.

After the defeat, Saladin tried to go back to his old tactics of small attacks, but they didn't work well. He was shaken by the Crusaders' sudden and powerful counterattack at Arsuf. He was no longer willing to risk another big battle. Arsuf damaged Saladin's reputation as an unbeatable warrior. It also proved Richard's bravery as a soldier and his skill as a commander.

Richard was able to take, defend, and hold Jaffa. This was a very important step towards securing Jerusalem. Saladin also had to leave and destroy most of the fortresses in southern Palestine. These included Ascalon, Gaza, Blanche-Garde, Lydda, and Ramleh. He realized he couldn't hold them. Richard even took the fortress of Darum, which Saladin had guarded, with only his own small group of soldiers. This showed how low Muslim morale had become. By taking control of the coast, Richard seriously threatened Saladin's hold on Jerusalem. Richard spent time in Jaffa rebuilding the walls that Saladin had destroyed earlier.

In the end, the Third Crusade didn't manage to retake Jerusalem. However, a three-year peace agreement was made with Saladin. This agreement, called the Treaty of Jaffa, allowed Christian pilgrims from the west to visit Jerusalem again. Saladin also recognized that the Crusaders controlled the coast as far south as Jaffa. Both sides were tired from the fighting. Richard needed to return to Europe to protect his lands from the King of France, and Palestine was in ruins.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |