Medieval Jerusalem facts for kids

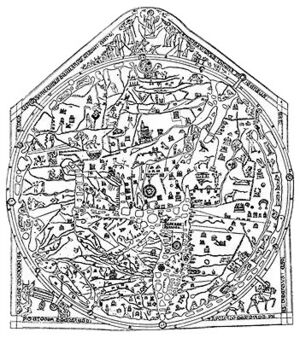

Jerusalem in the Middle Ages was a big city under the Byzantine Empire starting in the 300s CE. Then, in the 600s, it became the main city of a region called Jund Filastin under different caliphates (Islamic rulers). Later, Jerusalem faced more wars and became less important. Christian rulers from the Crusades took control for about 200 years, creating the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, the city was given to the Ottomans in 1517. They ruled it until the British took it in 1917.

Jerusalem grew during the Byzantine and early Islamic periods. But under the Fatimid caliphate in the late 900s, its population dropped from about 200,000 to less than half. When the Crusaders attacked in 1099 during the siege, many people living there were killed. The city's population grew back quickly during the Kingdom of Jerusalem. However, it fell again to less than 2,000 people when the Khwarezmi Turks took it in 1244. Jerusalem remained a smaller city under the Ayyubids, Mameluks, and Ottomans. Its population did not go above 10,000 again until the 1500s.

Contents

- What "Middle Ages" Means for Jerusalem

- Jerusalem Under Byzantine Rule

- Early Muslim Period (637/38–1099)

- Crusader Control

- Khwarezmian Control

- Ayyubid Control

- Mamluk Control and Mongol Raids

- Mamluk Rebuilding

- Ottoman Era

- See also

What "Middle Ages" Means for Jerusalem

When we talk about Jerusalem's history, archaeologists like S. Weksler-Bdolah say the "Middle Ages" (or medieval period) usually means the 1100s and 1200s.

Jerusalem Under Byzantine Rule

Jerusalem was at its biggest and had the most people around the end of the Second Temple period. The city covered about 2 square kilometers (0.8 sq mi) and had 200,000 people. For 500 years after the Bar Kokhba revolt in the 100s, the city was ruled by the Romans and then the Byzantines. In the 300s, the Roman Emperor Constantine I built Christian sites in Jerusalem, like the famous Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

A Christian monk named John Cassian lived near Bethlehem in the late 300s. He wrote that Jerusalem could be seen in four ways: as the actual city of the Jews, as the "Church of Christ," as the heavenly city of God, and as the human soul.

In 603, Pope Gregory I asked Abbot Probus to build a hospital in Jerusalem. This hospital was for Christian travelers visiting the Holy Land. In 800, Charlemagne made Probus's hospital bigger and added a library. But in 1005, a ruler named Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah destroyed it along with many other buildings in Jerusalem.

From Constantine's time until the Arab conquest in 637-638, Jewish people were not allowed to enter Jerusalem. After the Arabs took the city, Muslim rulers like Umar ibn al-Khattab allowed Jews to return. From the 700s to the 1000s, Jerusalem became less important as different Arab powers fought for control.

Early Muslim Period (637/38–1099)

Rashidun Caliphate (630s–661)

Muslims Take Control of the Area

Muslims, led by commander Amr ibn al-As, conquered southern Palestine. This happened after they won a big battle against the Byzantines at Battle of Ajnadayn in 634. This battle was likely fought about 25 km (15.5 mi) southwest of Jerusalem. Even though Jerusalem itself was not yet taken, a Christmas sermon in 634 showed that Muslim Arabs already controlled the areas around the city. The Christian leader, Patriarch Sophronius of Jerusalem, could not travel to nearby Bethlehem for a religious holiday because Arab raiders were present.

By 635, southern Syria was under Muslim control, except for Jerusalem and Caesarea. Around 636–637, Sophronius wrote sadly about the killings, raids, and churches being destroyed by the Arabs.

Siege and Surrender of Jerusalem

It's not exactly clear when Jerusalem was captured, but most experts say it was in the spring of 637. That year, the Muslim army, led by Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, surrounded the city. Historical records say that Caliph Umar (who ruled from 634 to 644) visited the Muslim camp in Syria in 637–638. He came to deal with many new rules for the conquered area. While there, Umar talked with a group from Jerusalem about the city's surrender. The Christian leader insisted on surrendering directly to the Caliph, not his commanders.

The earliest Muslim stories about Jerusalem's capture say that an Arab commander named Khalid ibn Thabit al-Fahmi arranged the surrender. The terms allowed Muslims to control the countryside and protected the city's people. In return, the people had to pay a tax. Khalid ibn Thabit was sent by Umar. Many historians believe this story is the most reliable. Other accounts also mention a treaty between the Muslims and Jerusalem's people, with similar terms.

The agreement for Jerusalem was generally good for the city's Christians. It promised safety for them, their property, and their churches. It also allowed them to practice their religion freely if they paid a special tax called jizya (a poll tax). Byzantine soldiers and others who wanted to leave the city were promised safe passage. One historian believes Umar was lenient so that the people could continue their lives and work, which would help support the Arab soldiers in Palestine.

The treaty also said that Jewish people could not live in Jerusalem alongside Christians. This rule had been in place since the time of Emperor Hadrian (who ruled from 117 to 138) and was renewed by Emperor Constantine (who ruled from 306 to 337). Later Christian writers said that Sophronius negotiated this ban on Jews living in Jerusalem.

Several later Muslim and Christian stories, and an 11th-century Jewish record, mention Caliph Umar visiting Jerusalem. Some stories say that Jewish people guided Umar and showed him the Temple Mount. In Muslim and Jewish accounts, a Jewish convert to Islam suggested that Umar pray behind the Holy Rock. Umar refused, saying that the Ka'aba in Mecca was the only direction for Muslim prayer. Jerusalem had been the first direction for prayer until Muhammad changed it to the Ka'aba.

Muslim and Jewish sources reported that the Temple Mount was cleaned by Muslims and a group of Jews from the city. The Jewish account also said that Umar watched the cleaning and talked with Jewish elders. Christian accounts said Umar visited Jerusalem's churches but refused to pray in them. He did this to avoid setting a rule that future Muslims would have to pray in Christian holy places.

After the Conquest: How Jerusalem Was Run

Jerusalem was likely the main Muslim political and religious center in Jund Filastin (the district of Palestine) after the conquest. This lasted until the city of Ramla was founded in the early 700s. Some historians believe that from Umar's time, Palestine had two capitals: Jerusalem and Lydda, each with its own governor and soldiers. A group of soldiers from Yemen was stationed in Jerusalem during this time.

Christian leaders in Jerusalem faced problems after Sophronius died around 638. No new Christian leader was appointed until 702. Still, Jerusalem remained mostly Christian during the early Islamic period. Soon after the conquest, perhaps in 641, Umar allowed a small number of Jews to live in Jerusalem. This happened after talks with the city's Christian leaders. A Jewish record from the 1000s says that Jews asked to settle 200 families, but Christians only agreed to 50. Umar finally decided on 70 families from Tiberias. One historian thinks the Caliph did this because he recognized the importance of Jews in the area, both for their numbers and their wealth. He also wanted to reduce Christian control over Jerusalem.

At the time of the conquest, the Temple Mount was in ruins. Byzantine Christians had mostly left it unused for religious reasons. Muslims took over the site for government and religious purposes. This was likely because the Temple Mount was a large, empty space in Jerusalem. Also, the surrender terms prevented Muslims from taking Christian property. Jewish converts to Islam might have also told early Muslims about the site's holiness. The early Muslims might have also wanted to show they disagreed with the Christian belief that the Temple Mount should stay empty. Also, early Muslims might have felt a spiritual connection to the site before they conquered it. Using the Temple Mount gave Muslims a huge space overlooking the whole city. It was probably used for Muslim prayer from the start of Muslim rule. This was because the surrender agreement stopped Muslims from using Christian buildings. Umar might have allowed this use of the Temple Mount. Stories from the 1000s say that Jews were hired to take care of and clean the Temple Mount. These workers did not have to pay the jizya tax.

The first Muslim settlements were built south and southwest of the Temple Mount, in areas with few people. Most Christian settlements were in western Jerusalem, around Golgotha and Mount Zion. The first Muslim settlers in Jerusalem mainly came from the Ansar, who were people from Medina. This included Shaddad ibn Aws, a nephew of a famous companion of Muhammad. Shaddad died and was buried in Jerusalem between 662 and 679. His family remained important there, and his tomb later became a respected place. Another important companion, Ubada ibn al-Samit, also settled in Jerusalem and became the city's first qadi (Islamic judge). The father of Muhammad's Jewish wife and a Jewish convert from Medina, Sham'un, settled in Jerusalem. He gave Muslim sermons on the Temple Mount. A woman named Umm al-Darda, the wife of the first judge of Damascus, lived in Jerusalem for half of the year. Caliph Uthman (who ruled from 644 to 656) was said to have used money from the rich vegetable gardens of Silwan, outside the city, to help the city's poor. These gardens would have been Muslim property after the surrender.

Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

Sufyanid Period (661–684)

Caliph Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan (who ruled from 661 to 680) founded the Umayyad Caliphate. He had been the governor of Syria under earlier caliphs. He opposed the next caliph, Ali, and made an agreement with Amr ibn al-As in Jerusalem in 658.

According to old records, Mu'awiya received promises of loyalty as caliph in Jerusalem at least twice between 660 and July 661. While the exact dates are unclear, Muslim and non-Muslim accounts agree that these promises were made at a mosque on the Temple Mount. This mosque might have been built by Umar and made bigger by Mu'awiya. The records say that "many leaders and Arab nomads gathered [at Jerusalem] and gave their loyalty to Mu'awiya." Afterward, he prayed at Golgotha and then at Mary's Tomb in Gethsemane. Mu'awiya prayed at Christian sites to show respect for the Syrian Arabs, who were mostly Christian and supported his power.

Mu'awiya's son and successor, Yazid I (who ruled from 680 to 683), might have visited Jerusalem several times. One historian thinks these visits were to show his power as caliph to Muslims.

Marwanid Period (684–750)

The Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (who ruled from 685 to 705) also received his promises of loyalty in Jerusalem. He had been the governor of Palestine. From the start of his rule, Abd al-Malik planned to build the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount. The Dome of the Rock was finished in 691–692. It was the first great example of Islamic architecture. The building was overseen by the Caliph's adviser and a local helper. The Dome of the Chain on the Temple Mount is also generally believed to have been built by Abd al-Malik.

Abd al-Malik is also credited with building two gates of the Temple Mount: the Prophet's Gate and the Mercy Gate. He also fixed the roads connecting his capital, Damascus, to Palestine and linking Jerusalem to its surrounding areas. Milestones found along these roads show this work. The oldest milestone is from May 692, and the latest is from September 704. These road projects were part of the Caliph's plan to centralize his rule. Palestine was important because it was a key travel area between Syria and Egypt, and Jerusalem was religiously central to the Caliph.

Many buildings were constructed on the Temple Mount and outside its walls under Abd al-Malik's son and successor, al-Walid I (who ruled from 705 to 715). Most historians believe al-Walid built the al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount. However, some think it might have been started by earlier Umayyad rulers, and al-Walid finished parts of it. Records show that workers from Egypt were sent to Jerusalem for six months to a year to work on the al-Aqsa Mosque, al-Walid's palace, and another building.

Al-Walid's brother and successor, Sulayman (who ruled from 715 to 717), was first recognized as caliph in Jerusalem. He lived in Jerusalem for some time during his rule and built a bathhouse there. However, Sulayman might not have loved Jerusalem as much as his predecessors. He built a new city called Ramla, about 40 km (25 mi) northwest of Jerusalem. Over time, Ramla became the main administrative and economic capital of Palestine, which made Jerusalem less important.

According to a Byzantine historian, Jerusalem's walls were destroyed by the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, in 745. This happened after the Caliph put down a rebellion by Arab tribes in Palestine.

Muslim Pilgrimage in the Umayyad Period

During the Umayyad period, Muslim religious ceremonies and pilgrimages in Jerusalem focused on the Temple Mount. Other important sites included the Prayer Niche of David (possibly the Tower of David), the Spring of Silwan, the Garden of Gethsemane, Mary's Tomb, and the Mount of Olives. The Umayyads encouraged Muslims to visit and pray in Jerusalem. Stories from this time celebrated the city. During this period, Muslim pilgrims came to Jerusalem to prepare themselves before going on the Umra or Hajj pilgrimages to Mecca. Muslims who could not make the pilgrimage, and possibly Christians and Jews, donated olive oil to light up the al-Aqsa Mosque. Most Muslim pilgrims to Jerusalem likely came from Palestine and Syria, but some came from far away parts of the Caliphate.

Abbasids, Tulunids, and Ikhshidids (750–969)

The Umayyads were overthrown in 750 by the Abbasid dynasty. The Abbasids then ruled the Caliphate, including Jerusalem, for the next two centuries, with some breaks. This time period is not well-documented. Any building work focused on repairing structures on the Temple Mount that were damaged by earthquakes. Caliphs al-Mansur (who ruled from 754 to 775) and al-Mahdi (who ruled from 775 to 785) ordered major rebuilding of the al-Aqsa Mosque after earthquake damage.

After the first Abbasid period (750–878), the Tulunids, a dynasty of Turkic origin, ruled Egypt and much of Syria, including Palestine, for almost 30 years (878–905). Ahmad ibn Tulun, the founder of this dynasty, took control of Palestine between 878 and 880. He passed it on to his son when he died in 884. According to a Christian leader, Ibn Tulun ended a period of persecution against Christians. He named a Christian governor in Ramla (or perhaps Jerusalem), who started renovating churches in the city. Ibn Tulun had a Jewish doctor and was generally relaxed towards non-Muslims. When he was dying, both Jews and Christians prayed for him. Ibn Tulun was the first of several Egyptian rulers of Palestine.

The Abbasids took back control over Jerusalem in 905. Between 935 and 969, it was managed by their Egyptian governors, the Ikhshidids. During this entire period, Jerusalem's religious importance grew. Several Egyptian rulers chose to be buried there.

The mother of Caliph al-Muqtadir (who ruled from 908 to 932) had wooden porches built under all the city gates and repaired the Dome of the Rock.

The Ikhshidid period saw some persecution of Christians. In 937, Muslims attacked the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, setting it on fire and stealing its treasures. These tensions were linked to the threat from the Byzantines. In this situation, Jews joined forces with Muslims. In 966, a Muslim and Jewish crowd, encouraged by the Ikhshidid governor, attacked the Church of the Holy Sepulchre again. The fire caused the dome over Jesus' Tomb to collapse and killed the Christian leader John VII.

Fatimids and Seljuks (970–1099)

The start of the first Fatimid period (970–1071) saw a mostly Berber army conquer the region. After 60 years of war and 40 years of peace, Turkish tribes invaded the region. This started a time of constant fighting against each other and the Fatimids. In less than 30 years of war and destruction, much of Palestine was ruined, causing terrible hardship, especially for the Jewish population. However, Jewish communities stayed in their places, only to be forced out after 1099 by the Crusaders. Turkish rule meant more than 25 years of constant warfare. This negatively affected local Christian communities and eventually blocked access for pilgrims from Europe. This blocking of pilgrims is seen as one reason for the Crusades to begin. We also know about a visitor from Muslim Spain who wrote a report in 1093–95 about the busy Sunni schools in Jerusalem and his interactions with Jews and Christians.

Between 1071 and 1076, Turkman tribes captured Palestine, and Jerusalem fell in 1073. These Turcomans acted independently but were linked to the Seljuk dynasty. Seljuk leader Atsiz ibn Uvaq al-Khwarizmi, from the Nawaki tribe, surrounded and captured Jerusalem in 1073. He held it for four years. Atsiz placed the land he captured under the rule of the Abbasid caliphate. In 1077, after a failed attempt to capture Cairo, he found that the people of Jerusalem had rebelled. They forced his soldiers to hide in the citadel and captured the families and belongings of the Turcomans. Atsiz then surrounded Jerusalem again. He promised the defenders safety if they surrendered. They did, but Atsiz broke his promise and killed 3,000 people, including those who had hidden in the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Only those inside the Dome of the Rock were spared. In 1079, Atsiz was killed by his ally Tutush, who then made Abbasid rule stronger in the area.

After Atsiz, other Seljuk commanders ruled Jerusalem and used it as a base for their wars. A new period of trouble began in 1091 when Tutush's governor in Jerusalem, Artuq, died. His two sons, who were bitter rivals, took over. The city changed hands between them several times. Finally, in August 1098, the Fatimids took back control of the city. They used the chance given by the approaching First Crusade. They ruled Jerusalem for less than a year.

Crusader Control

Stories of Christians being killed and the Byzantine Empire being defeated by the Seljuqs led to the First Crusade. Europeans marched to take back the Holy Land. On July 15, 1099, Christian soldiers won the Siege of Jerusalem, which lasted one month. The Jews had helped defend Jerusalem against the Crusaders because they were allied with the Muslims. When the city fell, the Crusaders killed most of the Muslim and Jewish people living there.

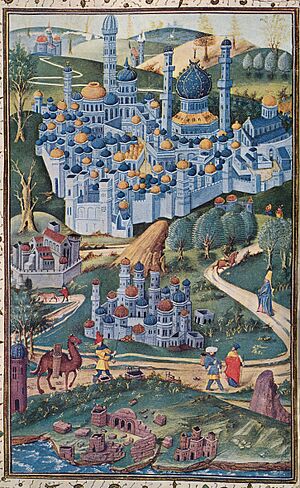

Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Christian settlers from the West began to rebuild the main holy sites linked to the life of Christ. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was rebuilt as a large Romanesque church. Muslim holy places on the Temple Mount (the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque) were changed for Christian use.

The Military Orders of the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar were created during this time. Both groups were formed to protect and care for the many pilgrims coming to Jerusalem. This was important because Bedouin raids and attacks by remaining Muslim groups continued on the roads. King Baldwin II of Jerusalem allowed the Templars to set up their headquarters in the captured Al-Aqsa Mosque. The Crusaders believed the Mosque was built on the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. So, they called the Mosque "Solomon's Temple" in Latin. This is how the Order got its name, "Temple Knights" or "Templars."

Under the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the area saw a great revival. This included rebuilding the city and harbor of Caesarea. The city of Tiberias was restored and fortified. The city of Ashkelon was expanded. Jaffa was walled and rebuilt. Bethlehem was reconstructed. Dozens of towns were repopulated. Large-scale farming was restored, and hundreds of churches, cathedrals, and castles were built.

The old hospice, rebuilt in 1023 at the site of the monastery of Saint John the Baptist, was expanded into a hospital. This was done under the Hospitaller leader Raymond du Puy de Provence near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

In 1173, Benjamin of Tudela visited Jerusalem. He described it as a small city with many Jacobites, Armenians, Greeks, and Georgians. Two hundred Jews lived in a part of the city near the Tower of David.

In 1187, with the Muslim world united under Saladin, Jerusalem was taken back by the Muslims. This happened after a successful siege. As part of this same campaign, Saladin's armies conquered, expelled, enslaved, or killed the remaining Christian communities in Galilee, Samaria, Judea, and the coastal towns.

In 1219, the city's walls were torn down by order of Al-Mu'azzam, the Ayyubid sultan of Damascus. This left Jerusalem without defenses and greatly hurt the city's importance.

After another Crusade by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in 1227, the city was given back by Saladin's relative, al-Kamil. This was part of a diplomatic treaty in 1228. It stayed under Christian control. The treaty said that no walls or defenses could be built in the city or along the strip connecting it to the coast. In 1239, after the ten-year truce ended, Frederick ordered the walls to be rebuilt. But without the strong Crusader army he had used ten years before, his plans were stopped. The walls were torn down again by an-Nasir Da'ud, the emir of Kerak, in the same year.

In 1243, Jerusalem was firmly back under the power of the Christian Kingdom, and the walls were repaired. However, this period was very short. A large army of Turkish and Persian Muslims was advancing from the north.

Khwarezmian Control

Jerusalem fell again in 1244 to the Khwarazmian Empire. These people had been forced out of their own lands by the Mongol invasion. As the Khwarezmians moved west, they joined forces with the Egyptians, under the Egyptian Ayyubid sultan as-Salih Ayyub. He hired Khwarezmian horsemen and sent the rest of the Khwarezmian army into the Levant. He wanted to build a strong defense against the Mongols there.

The Khwarezmians killed many local people, especially in Jerusalem. Their Siege of Jerusalem began on July 11, 1244. The city's fortress, the Tower of David, surrendered on August 23. The Khwarezmians then greatly reduced the population, leaving only 2,000 people (Christians and Muslims) still living in the city. This attack caused Europeans to start the Seventh Crusade. However, the new forces of King Louis IX of France did not succeed in Egypt, let alone reach Palestine.

Ayyubid Control

After having problems with the Khwarezmians, Sultan as-Salih started sending armed groups to raid Christian communities. They captured men, women, and children. These raids, called razzias or ghazw, reached into Caucasia, the Black Sea, Byzantium, and the coastal areas of Europe.

The newly enslaved people were divided into groups. Women became maids. Men, depending on their age and strength, became servants or were killed. Young boys and girls were sent to religious teachers, where they learned about Islam. Depending on their abilities, young boys were then made into eunuchs or trained for decades as mamluk (slave soldiers). This army of trained slaves became a powerful fighting force. The Sultan then used this new army to defeat the Khwarezmians. Jerusalem returned to Ayyubid rule in 1247.

Mamluk Control and Mongol Raids

When al-Salih died, his wife, Shajar al-Durr, became the ruler. She then gave power to the Mamluk leader Aybeg, who became Sultan in 1250. Meanwhile, the Christian rulers of Antioch and Cilician Armenia joined the Mongols. They fought with the Mongols as the Mongol Empire expanded into Iraq and Syria. In 1260, part of the Mongol army moved towards Egypt. They were met by the Mamluks in Galilee at the important Battle of Ain Jalut. The Mamluks won, and the Mongols retreated. In early 1300, there were some Mongol raids into the southern Levant again. This was shortly after the Mongols had captured cities in northern Syria. However, the Mongols only stayed for a few weeks and then went back to Iran. The Mamluks regrouped and took back control of the southern Levant a few months later, with little resistance.

There is not much clear evidence to say if the Mongol raids reached Jerusalem in 1260 or 1300. Historical reports from that time often disagree, depending on who wrote them. There were also many rumors in Europe that the Mongols had captured Jerusalem and would give it back to the Crusaders. However, these rumors were false. Most modern historians agree that even if Jerusalem was raided, the Mongols never tried to make it part of their government. This is what would be needed to call a place "conquered" instead of just "raided."

Mamluk Rebuilding

Even during the conflicts, a small number of pilgrims continued to come to Jerusalem. Pope Nicholas IV made an agreement with the Mamluk sultan to allow Latin Christian priests to serve in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. With the Sultan's agreement, Pope Nicholas sent a group of friars to keep the Latin church services going in Jerusalem. Since the city was not very important at the time, they had no official living quarters. They simply lived in a pilgrim hostel. Then, in 1300, King Robert of Sicily gave a large amount of money to the Sultan. Robert asked that the Franciscans be allowed to have the Sion Church, the Mary Chapel in the Holy Sepulchre, and the Nativity Cave. The Sultan agreed. But the other Christian holy places were left to decay.

Mamluk sultans made sure to visit the city. They built new buildings, encouraged Muslims to settle there, and made mosques bigger. During the rule of Sultan Baibars, the Mamluks renewed their alliance with the Jews. He built two new holy places: one for Moses near Jericho and one for Salih near Ramla. This was to encourage many Muslim and Jewish pilgrims to be in the area at the same time as Christians, who filled the city during Easter. In 1267, Nahmanides (also known as Ramban) moved to Jerusalem. In the Old City, he built the Ramban Synagogue, which is the oldest active synagogue in Jerusalem. However, the city had no great political power. The Mamluks actually considered it a place to send officials who had fallen out of favor. The city itself was ruled by a low-ranking leader.

After the persecutions of Jews during the Black Death, a group of Ashkenazi Jews led by Rabbi Isaac Asir HaTikvah moved to Jerusalem. They founded a religious school called a yeshiva. This group was part of the beginning of a much larger community that grew in the Ottoman period.

Ottoman Era

In 1517, Jerusalem and its surrounding areas came under the control of the Ottoman Turks. They would rule the city until the 1900s. Even though Europeans no longer controlled any land in the Holy Land, Christians, including Europeans, remained in Jerusalem. During the Ottoman period, this Christian presence grew. Greeks, with the support of the Turkish Sultan, rebuilt, restored, or constructed Orthodox Churches, hospitals, and communities. This era saw the first expansion of the city outside the Old City walls. New neighborhoods were built to ease the overcrowding that had become common. The first of these new neighborhoods included the Russian Compound and the Jewish Mishkenot Sha'ananim, both founded in 1860.

See also

- Aelia Capitolina

- Demographic history of Jerusalem

- Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Old City of Jerusalem

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |