History of the Byzantine Empire facts for kids

The Byzantine Empire was a powerful and long-lasting empire that grew out of the eastern part of the old Roman Empire. Its story generally starts in the late 300s AD and continues until 1453 AD, when its capital, Constantinople, was finally captured.

The Roman Empire was huge, stretching across Europe, Africa, and Asia. Over time, the eastern and western parts of the empire grew apart. In 285 AD, Emperor Diocletian officially divided the administration. Later, in 330 AD, Emperor Constantine I built a new capital city in the East called Constantinople. Christianity also became the official religion under Emperor Theodosius I.

Under Emperor Heraclius (610–641 AD), the empire changed a lot. Its army and government were reorganized, and Greek became the main language instead of Latin. Even though the Byzantine Empire was a continuation of the Roman Empire, historians often see it as a new era because of these big changes, especially the move of the capital and the shift to Greek language.

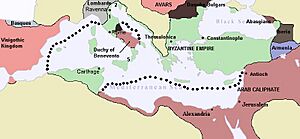

The empire's borders changed many times, like a wave, with periods of growth and decline. During the reign of Emperor Justinian I (527–565 AD), the empire was at its largest. It took back many parts of the old Roman western Mediterranean, including North Africa, Italy, and even Rome itself. These areas stayed under Byzantine control for about 200 more years.

Emperor Maurice (582–602 AD) expanded the eastern border and made the northern areas safe. But his murder led to a long, costly war with Persia. This war weakened the empire, making it easy for Muslim armies to conquer its richest provinces, Egypt and Syria, in the 600s.

During the Macedonian dynasty (800s–1000s), the empire grew strong again and had a period of great cultural and military success. This "renaissance" ended when much of Asia Minor was lost to the Seljuk Turks after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. This battle allowed the Turks to settle in Anatolia, which became their homeland.

In its final centuries, the empire slowly declined. It tried to recover in the 1100s, but it was badly hurt during the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Crusaders attacked and looted Constantinople, and the empire broke into smaller Greek and Latin states. Even though Constantinople was eventually recaptured and the empire was restored in 1261, it remained much smaller and weaker. Its remaining lands were gradually taken over by the Ottomans, until Constantinople finally fell to them in 1453, marking the end of the Roman Empire.

Contents

Early Roman Empire Divisions

Diocletian's Tetrarchy System

In the 200s AD, the Roman Empire faced huge problems. There were constant invasions from outside, civil wars within, and a struggling economy. The city of Rome became less important as a center of government. The old system of ruling the vast empire, set up by Emperor Augustus, was not working anymore. A new, stronger system was needed.

Emperor Diocletian created a new way to rule called the "tetrarchy." This meant "rule by four." He chose a co-emperor, called an Augustus, to help him. Then, each Augustus would adopt a younger helper, called a Caesar. These Caesars would share in the rule and eventually take over from the senior emperors. However, after Diocletian and his co-emperor Maximian stepped down, the tetrarchy system fell apart. Emperor Constantine I replaced it with a system where sons inherited the throne.

Constantine I: A New Capital and Changes

Constantine I moved the capital of the empire and made big changes to its government and religion. In 330 AD, he founded Constantinople, a "second Rome," on the site of an old city called Byzantium. This new city was perfectly located for trade between East and West. It was also a great place to protect the Danube River and was close to the eastern borders. Constantine also started building the huge, strong walls of Constantinople, which were made even stronger in later years. Historians say that founding Constantinople created a lasting split between the Greek-speaking East and the Latin-speaking West of the empire. This change greatly affected the future of Europe.

Constantine built on the government changes started by Diocletian. He made the money system stable again, introducing a gold coin called the solidus, which became very valuable. He also changed the army. Under Constantine, the empire regained much of its military strength and had a time of peace and wealth. He even took back parts of Dacia (modern-day Romania) after defeating the Visigoths in 332 AD.

To manage the empire better, Constantine divided the responsibilities of the praetorian prefects. These officials used to handle both military and civil duties. Constantine gave them only civil power, creating regional prefects. This idea of separating military and civil power continued until the 600s.

Constantine also supported Christianity. It didn't become the only religion, but the emperor gave Christians special treatment. Church leaders were free from taxes, Christians were preferred for government jobs, and bishops were given legal duties. Constantine believed emperors should not decide church teachings. Instead, they should call together big church councils for that purpose. He called the Synod of Arles and the First Council of Nicaea, showing his role as a leader in the Church.

By 395 AD, Constantine's work had shaped the empire. The idea of sons inheriting the throne was firmly in place. Emperor Theodosius I, who died that year, left the empire to his two sons: Arcadius in the East and Honorius in the West. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule over both halves of the empire.

The Eastern Empire avoided many of the problems that the West faced. This was partly because it had stronger cities and more money. This allowed it to pay invaders to leave and hire foreign soldiers. Throughout the 400s, many invading armies swept through the Western Empire but left the East alone. Emperor Theodosius II made the walls of Constantinople even stronger, making the city almost impossible to attack. These walls were not broken until 1204. To keep the Huns, led by Attila, away, Theodosius paid them large amounts of gold. He also supported merchants in Constantinople who traded with the Huns.

His successor, Marcian, refused to keep paying the Huns. Luckily, Attila turned his attention to the Western Roman Empire. After Attila died in 453 AD, his empire fell apart. Constantinople then made good deals with the remaining Huns, who sometimes fought as soldiers in the Byzantine army.

Leonid Dynasty: New Leaders and Challenges

Leo I became emperor after Marcian. After Attila's empire fell, a general named Aspar, who was not Orthodox Christian, had a lot of power in Constantinople. Leo I managed to get rid of Aspar's influence by supporting the Isaurians, a group from southern Anatolia. Aspar and his son were killed in 471 AD. After this, Constantinople had Orthodox Christian leaders for centuries.

Leo was also the first emperor to be crowned by the Patriarch of Constantinople, the head of the church, instead of a military leader. This became a permanent change. In the Middle Ages, the religious crowning became much more important than the old military one. In 468 AD, Leo tried to take back North Africa from the Vandals, but he failed. By this time, the Western Roman Empire was much smaller, mostly just Italy and parts of the Balkans.

In 466 AD, Leo married his daughter Ariadne to an Isaurian man named Tarasicodissa, who then took the name Zeno. When Leo died in 474 AD, Zeno and Ariadne's young son, Leo II, became emperor with Zeno as his helper. When Leo II died later that year, Zeno became emperor. The end of the Western Roman Empire is sometimes marked by the year 476 AD, early in Zeno's reign. In that year, a Germanic general named Odoacer removed the last Western Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, but did not replace him.

To try and get Italy back, Zeno talked with the Ostrogoths, a Germanic group led by Theodoric, who had settled in Moesia. Zeno sent Theodoric to Italy as a military commander. After Odoacer fell in 493 AD, Theodoric, who had lived in Constantinople when he was young, ruled Italy on his own. By doing this, Zeno kept some control over Italy, at least in name, and got rid of a troublesome group from the Eastern Empire.

In 475 AD, Zeno was removed from power by Basiliscus, a general. But Zeno got his throne back 20 months later. However, he faced a new threat from another Isaurian, Leontius, who also claimed to be emperor. In 491 AD, Anastasius I, an older civil officer, became emperor. It took until 498 AD for his forces to finally defeat the Isaurian resistance. Anastasius proved to be a strong leader and good at managing the empire. He improved Constantine I's money system by setting the exact weight of the copper follis, a coin used every day. He also changed the tax system and got rid of a hated tax called the chrysargyron. When he died, the empire's treasury had a huge amount of gold, about 145,150 kilograms (320,000 pounds).

Justinian I and His Legacy

Justinian I became emperor in 527 AD. His time as ruler saw the Byzantine Empire grow into many of its old Roman lands. Justinian, who came from a farming family, may have already been in charge during the reign of his uncle, Justin I (518–527 AD). In 532 AD, to make his eastern border safe, Justinian signed a peace treaty with Khosrau I of Persia. He agreed to pay a large yearly tribute to the Persians. In the same year, Justinian survived a huge riot in Constantinople called the Nika riots, which ended with many thousands of rioters killed. This victory made Justinian's power very strong.

The conquests in the West began in 533 AD. Justinian sent his general Belisarius to take back the province of Africa from the Vandals, who had controlled it since 429 AD. The victory was surprisingly easy, but it took until 548 AD to fully defeat the local tribes. In Ostrogothic Italy, the deaths of Theodoric and his family left a weak ruler, Theodahad, on the throne. In 535 AD, a small Byzantine army easily took Sicily. But the Goths soon fought back harder. Victory finally came in 540 AD when Belisarius captured Ravenna, after successfully taking Naples and Rome.

However, the Ostrogoths soon reunited under a new leader, Totila, and captured Rome in 546 AD. Belisarius was called back by Justinian in 549 AD. The arrival of a new general, Narses, with a large army in late 551 AD, changed the tide for the Byzantines. Totila was defeated and died in battle. His successor, Teia, was also defeated. Even with some continued resistance and two invasions by other groups, the war for Italy was over. In 551 AD, Justinian also sent forces to help a noble in Visigothic Spain, and the Byzantine Empire held a small part of the Spanish coast for a while.

In the East, wars with Persia continued until 561 AD, when Justinian and Khusro agreed to a 50-year peace. By the mid-550s, Justinian had won victories in most areas, except for the Balkans, which were often attacked by the Slavs. In 559 AD, the empire faced a big invasion from the Kutrigurs and Sclaveni. Justinian called Belisarius out of retirement, but once the immediate danger passed, the emperor took charge himself. The news that Justinian was strengthening his Danube fleet made the Kutrigurs nervous, and they agreed to a treaty.

Justinian is most famous for his legal work. In 529 AD, a group of ten men, led by John the Cappadocian, updated the old Roman legal code. This new collection of laws was called the Corpus Juris Civilis, or "Justinian's Code." In another part, the Pandects, completed in 533 AD, they organized and explained the many different rulings of Roman legal experts. A textbook, the Institutiones, was also created to help teach law. The fourth part, the Novellae, contained new laws issued between 534 and 565 AD. Because of his religious policies, Justinian had conflicts with Jews, pagans, and different Christian groups. To completely end paganism, Justinian closed the famous philosophy school in Athens in 529 AD.

During the 500s, old Greek and Roman culture was still important in the Eastern Empire. But Christian ideas and culture became more and more dominant. Hymns written by Romanos the Melode helped develop church services. Architects and builders worked to complete the new Church of the Holy Wisdom, the Hagia Sophia. This amazing church was built to replace an older one destroyed during the Nika revolt. Today, Hagia Sophia is one of the most important buildings in architectural history. During the 500s and 600s, the empire was hit by several outbreaks of plague. These diseases greatly reduced the population, causing economic problems and weakening the empire.

After Justinian died in 565 AD, his successor, Justin II, refused to pay the large tribute to the Persians. Meanwhile, the Germanic Lombards invaded Italy. By the end of the century, only a third of Italy was still under Byzantine control. Justin's successor, Tiberius II, chose to pay the Avars to keep them away while fighting the Persians. Although Tiberius's general, Maurice, led a successful campaign in the East, the payments did not stop the Avars. They captured the Balkan fortress of Sirmium in 582 AD, and the Slavs began to move across the Danube River. Maurice, who became emperor after Tiberius, got involved in a Persian civil war. He helped the rightful Persian king, Khosrau II, get his throne back and married his daughter to him. Maurice's treaty with his new brother-in-law expanded the empire's lands in the East. This allowed the energetic emperor to focus on the Balkans. By 602 AD, a series of successful Byzantine campaigns had pushed the Avars and Slavs back across the Danube.

Heraclian Dynasty and Shrinking Borders

After Maurice was murdered by Phocas, Khosrau used this as an excuse to take back the Roman province of Mesopotamia. Phocas was an unpopular ruler, often described as a "tyrant." He was eventually removed from power in 610 AD by Heraclius, who sailed to Constantinople. After Heraclius became emperor, the Persians pushed deep into Asia Minor, taking Damascus and Jerusalem. They even took the True Cross, a holy relic, to their capital. Heraclius's counter-attack became like a holy war. A special image of Christ was carried as a military flag. Similarly, when Constantinople was saved from an Avar siege in 626 AD, the victory was credited to icons of the Virgin Mary, which were carried around the city walls. The main Persian army was destroyed in 627 AD, and in 629 AD, Heraclius returned the True Cross to Jerusalem in a grand ceremony. The war had exhausted both the Byzantine and Persian empires, leaving them very weak against the Arab forces that appeared in the following years. The Byzantines suffered a huge defeat in 636 AD, and the Persian capital fell in 634 AD.

Heraclius tried to heal the religious differences between different Christian groups by suggesting a compromise. However, by this time, Syria and Palestine, which had many of these groups, had already fallen to the Arabs. Egypt, another center for these groups, fell by 642 AD. Some historians believe that these Christian groups' mixed feelings about Byzantine rule might have made them less resistant to the Arab expansion.

Heraclius did succeed in starting a new ruling family, and his descendants held the throne, with some breaks, until 711 AD. Their reigns were marked by big threats from both the West and the East. These threats reduced the empire's territory to a small part of what it had been in the 500s. There was also a lot of internal trouble and cultural change.

The Arabs, now in control of Syria and the Levant, often raided deep into Asia Minor. From 674–678 AD, they even laid siege to Constantinople itself. The Arab fleet was finally pushed back using "Greek fire," a secret weapon. A 30-year peace treaty was signed between the empire and the Arab Caliphate. However, the raids into Anatolia continued. This led to the decline of classical city life. People in many cities either built smaller, stronger areas within their old walls or moved entirely to nearby fortresses. Constantinople itself shrank greatly in size, and like other cities, parts of it became more like rural areas. The city also stopped receiving free grain shipments in 618 AD, after Egypt fell to the Persians and then the Arabs.

The old system of semi-independent city governments disappeared. In its place, a new system called the "theme system" developed. This divided Asia Minor into "provinces" where armies were stationed. These armies also took on civil duties and reported directly to the emperor. This system helped the empire survive the external pressures and laid the groundwork for future gains. However, some historians argue that these changes were so big that the Byzantine state should be seen as a new successor state rather than a direct continuation of the Roman Empire.

Moving many troops from the Balkans to fight the Persians and Arabs in the East allowed Slavic peoples to gradually move south into the Balkan peninsula. Like in Anatolia, many cities there shrank to small, fortified settlements. In the 670s, the Bulgars were pushed south of the Danube by the arrival of the Khazars. In 680 AD, Byzantine forces sent to stop these new settlements were defeated. The next year, Emperor Constantine IV signed a treaty with the Bulgar leader Asparukh. This new Bulgarian state took control over several Slavic tribes that had previously been under Byzantine rule. In 687–688 AD, Emperor Justinian II led a successful campaign against the Slavs and Bulgars. But the fact that he had to fight his way from Thrace to Macedonia shows how much Byzantine power in the northern Balkans had weakened.

Constantinople was the only Byzantine city that remained relatively strong, even with a big drop in population and outbreaks of plague. However, the capital had its own political and religious conflicts. Emperor Constans II continued his grandfather Heraclius's religious policy, which faced strong opposition from both common people and church leaders. The most outspoken opponents were arrested and exiled. Constans became very unpopular in the capital and moved his home to Syracuse, Sicily, where he was eventually murdered. The Senate, a council of important people, became more important in the 600s and often disagreed with the emperors. The last Heraclian emperor, Justinian II, tried to break the power of the city's wealthy families by taxing them heavily and appointing "outsiders" to government jobs. He was removed from power in 695 AD and sought help from the Khazars and then the Bulgars. In 705 AD, he returned to Constantinople with the Bulgar army, took back the throne, and started a period of terror against his enemies. With his final overthrow in 711 AD, supported by the city's wealthy families again, the Heraclian dynasty ended.

The 600s were a time of huge change. The empire that once stretched from Spain to Jerusalem was now much smaller, mostly just Anatolia, Chersonesos, and some parts of Italy and the Balkans. The loss of land also brought cultural changes. City life was greatly disrupted, old literary styles were replaced by religious writings, and a new, more abstract art style appeared. It's surprising that the empire survived this period at all, especially since the Persian Empire completely collapsed against the Arab expansion. But a strong military reorganization helped it withstand the outside pressures and set the stage for the next dynasty's successes.

Internal Instability and Iconoclasm

Isaurian Dynasty and Religious Conflict

Emperor Leo III the Isaurian (717–741 AD) stopped the Muslim attack in 718 AD, with great help from the Bulgarian leader Tervel. Arab raids continued to trouble the empire during Leo III's reign, but the threat was never as great as that first attack. In just over 12 years, Leo went from being a simple Syrian farmer to the Emperor of Byzantium. Leo then began to reorganize the military districts in Asia Minor.

In 726 AD, Leo III ordered the removal of a large golden statue of Christ that was above the Chalke Gate, the main entrance to the Great Palace of Byzantium. The Chalke Gate was named after its large bronze doors. It had been destroyed in the Nika riots of 532 AD and rebuilt by Justinian I. When it was rebuilt, a large golden statue of Christ was placed over the doors.

By the early 700s, some people in the Byzantine Empire felt that religious statues and paintings, called "icons," were being worshipped instead of God. They believed icons were getting in the way of true worship. So, a movement called "iconoclasm" (meaning "image-breaking") began. Its goal was to "cleanse" the church by destroying all religious icons. The most important icon in all of Byzantium was the golden Christ over the Chalke Gate. Iconoclasm was more popular in Asia Minor and the Levant than in the European parts of the empire. Although Leo III was from Syria, there is no clear proof that he was strongly in favor of iconoclasm. His order to remove the golden Christ and replace it with a simple cross was likely to calm the growing public opposition to religious icons.

In 730 AD, Leo III issued a law that made iconoclasm the official policy throughout the empire. The destruction of the golden Christ in 726 AD marks the start of the "first iconoclast period" in Byzantine history. Iconoclasm remained strong during the reigns of Leo III's successors, especially his son Constantine V. In fact, Constantine V's iconoclast policies caused a revolt in 742 AD. The leader of this revolt, Artabasdus, actually overthrew Constantine V and ruled as emperor for a few months before Constantine V got his power back.

Leo III's son, Constantine V (741–775 AD), won important victories in northern Syria and greatly weakened the Bulgars. Like his father, Constantine V's son, Leo IV (775–780 AD), was an iconoclast. However, Leo IV was influenced by his wife Irene, who supported religious statues and images. When Leo IV died in 780 AD, his 10-year-old son, Constantine VI (780–797 AD), became emperor with his mother Irene as his regent (a temporary ruler). But before Constantine VI could rule on his own, his mother Irene took the throne for herself.

Empress Irene (797–802 AD) brought back the policy of supporting icons. In 787 AD, at the Council of Nicaea, supporting icons became the official church policy, canceling Leo III's law from 730 AD. So, the "first iconoclasm" period, from 726 AD to 787 AD, ended. A period of supporting icons began, lasting through the reigns of Irene and her successors.

In the early 800s, the Arabs captured Crete and attacked Sicily. But on September 3, 863 AD, a general named Petronas won a huge victory against the Arab leader of Melitene. The Bulgar threat also returned under their leader Krum. However, in 814 AD, Krum's son, Omortag, made peace with the Byzantine Empire.

The 700s and 800s were also marked by the big religious disagreement over Iconoclasm. As mentioned, icons were banned by Leo and Constantine, leading to revolts by those who supported icons. After Empress Irene's efforts, the Second Council of Nicaea met in 787 AD. It confirmed that icons could be honored but not worshipped.

Irene tried hard to stop iconoclasm everywhere, even in the army. During her reign, Arabs continued to raid the small farms in Asia Minor. These small farmers had a duty to serve in the Byzantine army, which was largely based on them. Irene's policy of supporting icons drove these farmers out of the army and off their farms. This weakened the army and left Anatolia unprotected from Arab raids. Many remaining farmers moved to Constantinople, further reducing the army's ability to find soldiers. Also, the abandoned farms no longer paid taxes, which reduced the government's income. These farms were often taken over by monasteries, which were the largest landowners in the empire. To make things worse, Irene had made all monasteries free from taxes.

Given the financial problems the empire faced, it's not surprising that Irene was eventually removed from power by her own finance minister. The leader of this successful revolt against Irene became emperor under the name Nicephorus I.

Nicephorus I (802–811 AD) was of Arab origin. He immediately worked to improve the empire's finances by ending Irene's tax exemptions and to strengthen the army by drafting poor farmers. However, Nicephorus I continued Irene's policy of supporting icons. Nicephorus I was killed in 811 AD while fighting the Bulgars under their King Krum. Nicephorus's son and successor, Stauracius (811 AD), was badly wounded in the same battle and died just six months later. Nicephorus I's daughter, Procopia, was married to Michael Rhangabe, who then became Emperor Michael I.

Irene reportedly tried to arrange a marriage between herself and Charlemagne, the powerful Western ruler. But this plan was stopped by one of her favorites. During Michael I's reign (811–813 AD), foreign policy with Charlemagne became important again. Since being crowned Emperor by the Pope in Rome in 800 AD, Charlemagne had been claiming parts of the Eastern Empire. Nicephorus I had refused to recognize Charlemagne's title and ignored his claims. This led to a naval war with the Franks, which indirectly caused Venice to officially separate from the Byzantine Empire. (Venice had been acting independently since 727 AD, but officially remained part of the empire until 811 AD.)

The threat from the Bulgars under King Krum, which became very clear in 811 AD, forced Michael I to change his policy towards Charlemagne. Michael I had to recognize Charlemagne and start peace talks to avoid fighting both the Franks and the Bulgars at the same time. This change in policy and the agreement with Charlemagne had long-term effects. Under the treaty, Charlemagne's imperial title over his lands in the West was recognized. In return, Charlemagne dropped all his claims to the Byzantine throne or any part of the empire. This treaty of 811 AD was a turning point. Until this date, despite centuries of separation, there was always a small hope that the two parts of the old Roman Empire might reunite. From 811 AD onwards, this hope was finally given up. There was no longer any idea of merging the two parts of the old Roman Empire.

Michael I was forced into this treaty with Charlemagne because of the Bulgar threat. His failure to succeed against the Bulgars led to a revolt against him, ending his reign in 813 AD. The army rose up against Michael I. The leader of this revolt was an Armenian commander who took the throne as Leo V.

Amorian Dynasty and the Second Iconoclasm

In 813 AD, Leo V the Armenian (813–820 AD) brought back the policy of iconoclasm. This started the "Second Iconoclasm" period, which lasted from 813 to 842 AD. Only in 843 AD did Empress Theodora, with the help of Patriarch Methodios, restore the honoring of icons. Iconoclasm played a part in further separating the Eastern and Western churches.

However, iconoclasm may have also helped feudalism grow in the Byzantine Empire. Feudalism is when central government power decreases, and power is given to private, local landowners. These private individuals become the new rulers over the common people living and working in their area. These landowners owe only military service to the central government when called upon. In return, they are given freedom to rule their local area. This practice had roots in earlier Roman history, where lands were given to soldiers in exchange for hereditary military service. With iconoclasm, many monasteries were stripped of their wealth, and church lands were taken by the emperor. These lands were given to private individuals. Their duty was again military service to the emperor. Although some of these lands were returned to monasteries under Empress Irene, feudalism had already taken root through the private control of these lands.

Macedonian Dynasty and a New Golden Age

The Byzantine Empire reached its peak under the Macedonian emperors (who were of Greek descent) from the late 800s to the early 1000s. During this time, the empire controlled the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy, and all the lands of Tsar Samuel of Bulgaria. Cities grew, and wealth spread across the provinces because of new safety. The population increased, and production went up, leading to more trade. Culturally, there was a lot of growth in education and learning. Old texts were saved and carefully copied. Byzantine art thrived, and beautiful mosaics decorated many new churches. Even though the empire was smaller than during Justinian's time, it was stronger because its remaining lands were closer together and more united.

Internal Changes and Strength

The "Macedonian Renaissance" is often linked to Emperor Basil I (867–886 AD), who started the Macedonian dynasty. However, it's also linked to the changes made by his predecessor, Michael III (842–867 AD), and his wife's smart advisor, Theoktistos. Theoktistos especially supported culture at court and, with careful money management, steadily increased the empire's gold reserves. The rise of the Macedonian dynasty happened at the same time as internal changes that made the empire's religious unity stronger. The iconoclast movement was fading, which allowed emperors to gently end the religious conflict that had drained the empire's resources for centuries.

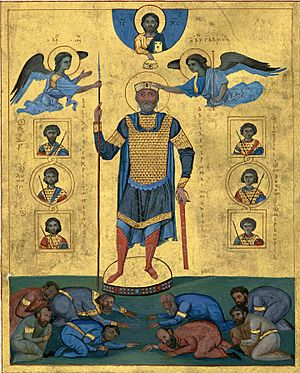

Despite occasional military losses, the government, laws, culture, and economy continued to improve under Basil's successors, especially with Romanos I Lekapenos (920–944 AD). The "theme system," which divided Asia Minor into military and administrative districts, reached its final form during this time. Once the government was safely back in the hands of those who supported icons, and monastery lands and privileges were returned, the church became a strong, loyal supporter of the emperor. Most of the Macedonian emperors (867–1056 AD) were against the interests of the rich noble families. They created many laws to protect and favor small farmers over the nobles. Before the Macedonian emperors, large landowners controlled much of society and owned most of the farmland. Since landowners owed military service to the emperor, having many small landowners meant larger armies than having a few large landowners. So, supporting small farmers created a stronger military for the empire. These policies helped the emperors become better at fighting wars against the Arabs.

Wars Against Muslim Powers

By 867 AD, the empire had become stable again in both the East and West. Its strong defense system allowed emperors to plan wars to take back lands in the East. This reconquest had mixed results. A temporary recapture of Crete (843 AD) was followed by a big Byzantine defeat. Emperors also couldn't stop the ongoing Muslim conquest of Sicily (827–902 AD). Using modern-day Tunisia as a starting point, Muslims conquered Palermo in 831 AD, Messina in 842 AD, and other cities, with the last Byzantine stronghold in Sicily falling in 902 AD.

However, these setbacks were balanced by a successful expedition against Damietta in Egypt (856 AD), a defeat of the Arab leader of Melitene (863 AD), and the confirmation of imperial control over Dalmatia (867 AD). Emperor Basil I also launched attacks towards the Euphrates River in the 870s. Unlike the worsening situation in Sicily, Basil I managed the situation in southern Italy well, and that province remained under Byzantine control for another 200 years.

In the early years of Basil I's reign, Arab raids on the coasts of Dalmatia were successfully stopped, and the region became safely Byzantine again. This allowed Byzantine missionaries to go inland and convert the Serbs and other groups to Orthodox Christianity. However, the attempt to retake Malta ended badly when the local people sided with the Arabs and killed the Byzantine soldiers. In contrast, the Byzantine position in Southern Italy slowly became stronger. By 873 AD, Bari was back under Byzantine rule, and most of Southern Italy stayed with the empire for the next 200 years. On the more important eastern front, the empire rebuilt its defenses and went on the attack. The Paulicians, a religious group, were defeated, and their capital was taken. The attack against the Abbasid Caliphate began with the recapture of Samosata.

Under Michael's son, Leo VI the Wise, the gains in the East against the now weak Abbasid Caliphate continued. However, Sicily was lost to the Arabs in 902 AD. In 904 AD, Thessaloniki, the empire's second-largest city, was looted by an Arab fleet. The empire quickly fixed its naval weakness. A few years later, a Byzantine fleet recaptured Cyprus, which had been lost in the 600s, and also attacked Laodicea in Syria. Despite this revenge, the Byzantines still couldn't deliver a decisive blow against the Muslims. The imperial forces suffered a crushing defeat when they tried to regain Crete in 911 AD.

The death of the Bulgarian tsar Simeon I in 927 AD greatly weakened the Bulgarians, allowing the Byzantines to focus on the eastern front. The situation on the border with Arab lands remained changeable, with the Byzantines sometimes attacking and sometimes defending. The Varangians (later known as the Russians), who attacked Constantinople for the first time in 860 AD, were another new challenge. In 941 AD, the Russians appeared on the Asian side of the Bosporus. But this time, they were crushed, showing how much the Byzantine military had improved after 907 AD, when only diplomacy had been able to push back the invaders. The general who defeated the Varangians/Russians was the famous John Kourkouas, who continued the attack with other important victories in Mesopotamia (943 AD). These Byzantine victories ended with the recapture of Edessa (944 AD). This was especially celebrated because the revered Mandylion, a relic believed to have a portrait of Jesus, was returned to Constantinople.

The soldier-emperors Nikephoros II Phokas (963–969 AD) and John I Tzimiskes (969–976 AD) expanded the empire deep into Syria. They defeated the Arab leaders of north-west Iraq and recaptured Crete and Cyprus. At one point under John, the empire's armies even threatened Jerusalem, far to the south. The Arab state of Aleppo and its neighbors became subject to the empire in the East. The biggest threat there was Caliph Hakim of the Fatimid caliphate. After many campaigns, the last Arab threat to Byzantium was defeated when Basil II quickly brought 40,000 mounted soldiers to help Roman Syria. With many resources and victories from the Bulgar and Syrian campaigns, Basil II planned an expedition to retake Sicily from the Arabs there. After his death in 1025 AD, the expedition set off in the 1040s and had some initial success, but it didn't fully succeed.

Wars Against the Bulgarians

The ongoing conflict with the Pope in Rome continued during the Macedonian period. This was fueled by the question of who had religious authority over the newly Christianized state of Bulgaria. Ending 80 years of peace, the powerful Bulgarian tsar Simeon I invaded in 894 AD. But the Byzantines pushed him back. They used their fleet to sail up the Black Sea to attack the Bulgarian rear, getting help from the Hungarians. However, the Byzantines were defeated in 896 AD and agreed to pay yearly payments to the Bulgarians.

Leo the Wise died in 912 AD, and fighting soon started again. Simeon marched to Constantinople with a large army. Although the city's walls were too strong to break, the Byzantine government was in chaos. Simeon was invited into the city, where he was crowned emperor of Bulgaria. He also had the young emperor Constantine VII marry one of his daughters. When a revolt in Constantinople stopped his plan to join the two royal families, he invaded Thrace again and conquered Adrianople. The empire now faced a strong Christian state very close to Constantinople, and had to fight on two fronts.

A large imperial expedition ended with another crushing Byzantine defeat in 917 AD. The following year, the Bulgarians were free to raid northern Greece. Adrianople was looted again in 923 AD, and a Bulgarian army besieged Constantinople in 924 AD. However, Simeon died suddenly in 927 AD, and Bulgarian power collapsed with him. Bulgaria and Byzantium entered a long period of peace, and the empire was now free to focus on the eastern front against the Muslims. In 968 AD, Bulgaria was overrun by the Rus' people. But three years later, John I Tzimiskes defeated the Rus' and brought Eastern Bulgaria back into the Byzantine Empire.

Bulgarian resistance revived under a new ruling family. But the new emperor Basil II (976–1025 AD) made defeating the Bulgarians his main goal. Basil's first expedition against Bulgaria, however, resulted in a humiliating defeat. For the next few years, the emperor was busy with internal revolts in Anatolia, while the Bulgarians expanded their lands in the Balkans. The war lasted for nearly 20 years. Byzantine victories greatly weakened the Bulgarian army. In yearly campaigns, Basil slowly took over Bulgarian strongholds. Finally, in 1014 AD, the Bulgarians were completely defeated. The Bulgarian army was captured, and it is said that 99 out of every 100 men were blinded, with the last man left with one eye to lead his comrades home. When Tsar Samuil saw the broken remains of his army, he died of shock. By 1018 AD, the last Bulgarian strongholds had surrendered, and the country became part of the empire. This huge victory restored the Danube border, which had not been held since the time of Emperor Heraclius.

Relations with Kiev Rus'

Between 850 and 1100 AD, the Byzantine Empire had a changing relationship with the new state of Kiev Rus' that emerged north of the Black Sea. The Byzantine Empire quickly became a main trading and cultural partner for Kiev. After the Rus' people became Christian, their leader Vladimir the Great hired many architects and artists to build churches around Rus', spreading Byzantine influence even further.

Kiev Princes often married into the Byzantine imperial family. Constantinople often hired the Princes' armies, most notably Vladimir the Great, who gave the Byzantines the famous Varangian Guard. This was an army of fierce Scandinavian soldiers. Some believe this was in exchange for Vladimir marrying Basil's sister, Anna. However, historical records state the marriage was in exchange for the Rus' converting to Orthodox Christianity. The creation of the Varangian Guard, though important, was a result of this exchange.

These relationships were not always friendly. During these 300 years, Constantinople and other Byzantine cities were attacked several times by the armies of Kiev Rus'. Kiev never went far enough to truly threaten the empire. These wars were mostly a way to force the Byzantines to sign better trade treaties. Constantinople, at the same time, constantly played Kiev Rus', Bulgaria, and Poland against each other.

The Byzantine influence on Kiev Rus' was huge. Byzantine-style writing became the basis for the Cyrillic alphabet. Byzantine architecture was popular in Kiev. As a main trading partner, Byzantium played a critical role in the rise and fall of Kiev Rus'.

The Empire's Peak

The Roman Empire then stretched from Armenia in the East to Calabria in Southern Italy in the West. Many successes had been achieved, from conquering Bulgaria to taking parts of Georgia and Armenia, and completely destroying an invading Egyptian army outside Antioch. Yet even these victories were not enough. Basil considered the continued Arab control of Sicily to be unacceptable. So, he planned to retake the island, which had belonged to the empire for over 300 years. However, his death in 1025 AD ended the project.

Leo VI completed the full organization of Byzantine law in Greek. This huge work of 60 volumes became the basis of all later Byzantine law and is still studied today. Leo also reformed the empire's government, redrawing the borders of the administrative regions and organizing the system of ranks and privileges. He also regulated the behavior of different trade groups in Constantinople. Leo's reforms greatly reduced the empire's earlier fragmentation. From then on, Constantinople was the single center of power. However, the empire's increasing military success greatly enriched the provincial noble families, giving them more power over the farmers, who were essentially reduced to a state of serfdom (like being tied to the land).

Under the Macedonian emperors, Constantinople thrived. It became the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, with about 400,000 people in the 800s and 900s. During this time, the Byzantine Empire had a strong civil service made up of skilled noblemen. They managed tax collection, internal affairs, and foreign relations. The Macedonian emperors also increased the empire's wealth by encouraging trade with Western Europe, especially through selling silk and metalwork.

The 1000s were also important for religious events. In 1054 AD, relations between the Greek-speaking Eastern Church and the Latin-speaking Western Church reached a breaking point. Although there was a formal declaration of separation on July 16, when papal representatives placed a document of excommunication on the altar in the Hagia Sophia, the "Great Schism" was actually the result of centuries of slow separation. While the split was caused by disagreements over religious teachings, arguments about church administration and political issues had been simmering for centuries. The official separation of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Western Roman Catholic Church would have big consequences for the future of Byzantium.

Crisis and Decline

The Byzantine Empire soon faced difficulties. These were largely caused by the weakening of the theme system and the neglect of the military. Emperors like Nikephoros II, John Tzimiskes, and Basil II changed the military divisions from a quick-response, defensive citizen army into a professional army that often used expensive foreign soldiers. However, mercenaries were costly. As the threat of invasion lessened in the 900s, so did the need for large garrisons and expensive forts. Basil II left a growing treasury when he died, but he didn't plan for who would rule after him. None of his immediate successors had much military or political skill, and the empire's government increasingly fell into the hands of civil servants. Efforts to revive the Byzantine economy only led to rising prices and a weaker gold currency. The army was now seen as both an unnecessary cost and a political threat. So, native troops were dismissed and replaced by foreign mercenaries.

At the same time, the empire faced new, ambitious enemies. Byzantine provinces in southern Italy faced the Normans, who arrived in Italy in the early 1000s. The combined forces of a local leader and the Normans were defeated in 1018 AD. Two decades later, Emperor Michael IV prepared an expedition to retake Sicily from the Arabs. Although the campaign started well, Sicily was not fully reconquered. This was mainly because the Byzantine commander, George Maniaces, was called back to Constantinople when he was suspected of having his own ambitious plans. During a period of conflict between Constantinople and Rome, which ended in the East–West Schism of 1054 AD, the Normans began to slowly but steadily advance into Byzantine Italy.

However, the biggest disaster happened in Asia Minor. The Seljuk Turks first explored across the Byzantine border into Armenia in 1065 and 1067 AD. This emergency gave power to the military noble families in Anatolia. In 1068 AD, they made one of their own, Romanos Diogenes, emperor. In the summer of 1071 AD, Romanos led a huge campaign to draw the Seljuks into a big battle. At Manzikert, Romanos not only suffered a surprise defeat by Sultan Alp Arslan but was also captured. Alp Arslan treated him with respect and didn't demand harsh terms from the Byzantines. In Constantinople, however, a coup (a sudden takeover of power) happened in favor of Michael Doukas. By 1081 AD, the Seljuks had expanded their rule over almost all of Anatolia, from Armenia in the East to Bithynia in the West, and set up their capital in Nicea.

Meanwhile, the Normans had wiped out the Byzantine presence in southern Italy. Reggio, the capital of Calabria, was captured by Robert Guiscard in 1060 AD. At that time, the Byzantines controlled only a few coastal cities in Apulia. Otranto fell in 1068 AD, the same year the siege of Bari began. After the Byzantines were defeated in several battles, and all attempts to help the city failed, Bari surrendered in April 1071 AD. This event ended the Byzantine presence in southern Italy.

Komnenian Dynasty and the Crusaders

A Period of Restoration

During the Komnenian period, from about 1081 to 1185 AD, five emperors from the Komnenos family (Alexios I, John II, Manuel I, Alexios II, and Andronikos I) led a strong, though not fully complete, recovery of the Byzantine Empire's military, land, economy, and political power. Even though the Seljuk Turks controlled the central part of Asia Minor, most Byzantine military efforts during this time were against Western powers, especially the Normans.

The Komnenian emperors played a key role in the history of the Crusades to the Holy Land. Alexios I helped bring about the First Crusade. The empire also had a huge cultural and political influence in Europe, the Near East, and the Mediterranean lands under John and Manuel. Contact between Byzantium and the "Latin" West, including the Crusader states, greatly increased during this period. Venetian and other Italian traders lived in large numbers in Constantinople and the empire. Their presence, along with many Latin mercenaries hired by Manuel, helped spread Byzantine technology, art, literature, and culture throughout the Latin West. At the same time, Western ideas and customs flowed into the empire.

In terms of wealth and cultural life, the Komnenian period was one of the best times in Byzantine history. Constantinople remained the leading city of the Christian world in size, wealth, and culture. There was a renewed interest in old Greek philosophy, and more literature was written in everyday Greek. Byzantine art and literature were very important in Europe, and their cultural impact on the West during this period was huge and lasted a long time.

Alexios I and the First Crusade

After the Battle of Manzikert, a partial recovery (called the Komnenian restoration) was made possible by the Komnenian dynasty. The first Komnenian emperor was Isaac I (1057–1059 AD). Then the Doukas family held power (1059–1081 AD). The Komnenos family regained power under Alexios I in 1081 AD. From the very start of his reign, Alexios faced a strong attack by the Normans. They captured cities and besieged Larissa. Robert Guiscard's death in 1085 AD temporarily eased the Norman problem. The next year, the Seljuk sultan died, and his empire split due to internal conflicts. Alexios, through his own efforts, defeated the Pechenegs, who were caught by surprise and destroyed in 1091 AD.

After achieving stability in the West, Alexios could focus on the serious economic problems and the weakening of the empire's defenses. However, he still didn't have enough soldiers to retake the lost lands in Asia Minor and advance against the Seljuks. At a church council in 1095 AD, Alexios's envoys spoke to Pope Urban II about the suffering of Christians in the East. They stressed that without help from the West, they would continue to suffer under Muslim rule.

Pope Urban saw Alexios's request as a chance to unite Western Europe and bring the Eastern Orthodox Churches back under the Roman Catholic Church. On November 27, 1095 AD, Pope Urban II called together the Council of Clermont. He urged everyone present to take up arms under the sign of the Cross and start an armed journey to take back Jerusalem and the East from the Muslims. The response in Western Europe was overwhelming.

Alexios had expected help in the form of mercenary soldiers from the West. But he was completely unprepared for the huge and unruly force that soon arrived in Byzantine territory. It was not comforting for Alexios to learn that four of the eight leaders of the main Crusader army were Normans, including Bohemund. Since the Crusade had to pass through Constantinople, the emperor had some control over it. He required its leaders to promise to return to the empire any towns or lands they might conquer from the Turks on their way to the Holy Land. In return, he gave them guides and military protection.

Alexios was able to retake several important cities and islands, and much of western Asia Minor. However, the Crusaders believed their promises were no longer valid when Alexios did not help them during the siege of Antioch. (He had actually set out for Antioch but was convinced to turn back by a Crusader who told him all was lost.) Bohemund, who had made himself Prince of Antioch, briefly went to war with the Byzantines. But he agreed to become Alexios's subject under a treaty in 1108 AD. This marked the end of the Norman threat during Alexios's reign.

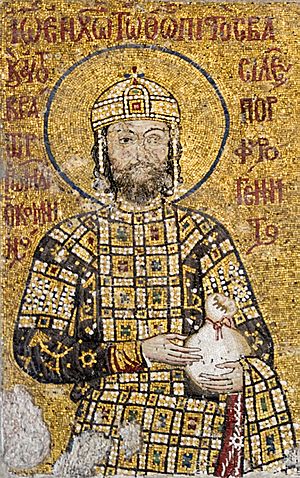

John II, Manuel I, and the Second Crusade

Alexios's son John II Komnenos became emperor in 1118 AD and ruled until 1143 AD. John was a religious and dedicated emperor who wanted to fix the damage his empire had suffered at the Battle of Manzikert, 50 years earlier. Famous for his religious devotion and his remarkably fair and gentle rule, John was an excellent example of a moral ruler, at a time when cruelty was common. For this reason, he has been called the Byzantine Marcus Aurelius. During his 25-year reign, John made alliances with the Holy Roman Empire in the West. He decisively defeated the Pechenegs and personally led many campaigns against the Turks in Asia Minor. John's campaigns greatly changed the balance of power in the East, forcing the Turks to defend themselves and returning many towns, forts, and cities across the peninsula to the Byzantines. He also stopped Hungarian and Serbian threats in the 1120s. In 1130 AD, he allied with the German emperor against the Norman King Roger II of Sicily.

In the later part of his reign, John focused on the East. He defeated the Danishmend Turks and reconquered all of Cilicia. He also forced Raymond of Poitiers, the Prince of Antioch, to recognize Byzantine authority. To show the Byzantine emperor's role as the leader of the Christian world, John marched into the Holy Land with the combined forces of Byzantium and the Crusader states. Yet, despite his great energy, John's hopes were disappointed by the betrayal of his Crusader allies. In 1142 AD, John returned to press his claims to Antioch, but he died in the spring of 1143 AD after a hunting accident. Raymond was encouraged to invade Cilicia, but he was defeated and forced to go to Constantinople to beg for mercy from the new emperor.

John's chosen heir was his fourth son, Manuel I Komnenos. Manuel aggressively campaigned against his neighbors in both the West and the East. In Palestine, he allied with the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem and sent a large fleet to join a combined invasion of Egypt. Manuel strengthened his position as overlord of the Crusader states, with his control over Antioch and Jerusalem secured by agreements. In an effort to restore Byzantine control over the ports of southern Italy, he sent an expedition to Italy in 1155 AD. But disagreements within his allies led to the campaign's failure. Despite this military setback, Manuel's armies successfully invaded the Kingdom of Hungary in 1167 AD, defeating the Hungarians. By 1168 AD, almost the entire eastern Adriatic coast was in Manuel's hands. Manuel made several alliances with the Pope and Western Christian kingdoms, and successfully managed the passage of the Second Crusade through his empire. Although hopes for a lasting alliance with the Pope faced big problems, Pope Innocent III clearly had a positive view of Manuel.

In the East, however, Manuel suffered a major defeat in 1176 AD against the Turks. Yet the losses were quickly made up. The following year, Manuel's forces defeated a group of "picked Turks." The Byzantine commander, John Vatatzes, who destroyed the Turkish invaders, not only brought troops from the capital but also gathered an army along the way. This showed that the Byzantine army remained strong and that the defense program in western Asia Minor was still working.

1100s Renaissance

John and Manuel actively pursued military policies. They spent a lot of resources on sieges and city defenses. Strong fortification policies were central to their imperial military plans. Despite the defeat, the policies of Alexios, John, and Manuel led to huge land gains, increased border stability in Asia Minor, and secured the empire's European borders. From about 1081 to 1180 AD, the Komnenian army kept the empire safe, allowing Byzantine civilization to flourish.

This safety allowed the Western provinces to experience an economic revival that continued until the end of the century. Some historians argue that Byzantium under Komnenian rule was wealthier than at any time since the Persian invasions of the 600s. During the 1100s, the population grew, and large areas of new farmland were put into use. Evidence from both Europe and Asia Minor shows a big increase in the size of cities, along with a noticeable rise in new towns. Trade was also thriving. The Venetians, Genoese, and others opened up the ports of the Aegean Sea to trade, shipping goods from the Crusader kingdoms and Egypt to the West and trading with the Byzantine Empire through Constantinople.

In art, there was a revival in mosaics. Regional schools of architecture began creating many unique styles that drew on various cultural influences. During the 1100s, the Byzantines offered their model of early humanism, showing a renewed interest in classical authors.

Decline and Fragmentation

Angeloi Dynasty and the Third Crusade

Manuel's death in 1180 AD left his 11-year-old son Alexios II Komnenos on the throne. Alexios was not good at ruling. His mother, Maria of Antioch, and her Western background made his regency unpopular. Eventually, Andronikos I Komnenos, a grandson of Alexios I, started a revolt against his younger relative. He managed to overthrow him in a violent takeover. Using his good looks and his huge popularity with the army, he marched on Constantinople in August 1182 AD and caused a massacre of the Latins (Western Europeans). After getting rid of his rivals, he was crowned co-emperor in September 1183 AD. He then killed Alexios II and even took his 12-year-old wife for himself.

This troubled succession weakened the family line and unity that the Byzantine state had come to rely on.

Andronikos started his reign well. Historians have praised the steps he took to reform the empire's government. Andronikos was determined to stop corruption. Under his rule, government jobs were no longer sold; people were chosen based on skill, not favoritism. Officials were paid enough to reduce the temptation of bribes. In the provinces, Andronikos's reforms led to quick and clear improvements. People felt his laws were strict but fair, and they were protected from greedy officials. Andronikos's efforts to control oppressive tax collectors and officials greatly helped the farmers. But his attempt to limit the power of the noble families was much harder. The aristocrats were furious with him. To make matters worse, Andronikos seemed to become more and more unstable. Executions and violence became common, and his reign turned into a period of terror. Andronikos seemed to want to destroy the aristocracy completely. The fight against the nobles turned into a widespread killing, while the emperor used increasingly brutal methods to keep his power.

Despite his military background, Andronikos failed to deal with several threats. He couldn't stop Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus, or Béla III of Hungary, who took back Croatian lands. Stephen Nemanja of Serbia also declared his independence from Byzantium. Yet none of these problems compared to William II of Sicily's invasion force of 300 ships and 80,000 men, which arrived in 1185 AD. Andronikos gathered a small fleet of 100 ships to defend the capital, but otherwise, he seemed indifferent to the people. He was finally overthrown when Isaac Angelos, surviving an assassination attempt, seized power with the help of the people and had Andronikos killed.

The reigns of Isaac II and, even more so, his brother Alexios III, saw the collapse of what was left of the Byzantine government and defense. Although the Normans were driven out of Greece, in 1186 AD, the Vlachs and Bulgars started a rebellion that led to the formation of the Second Bulgarian Empire. The poor management of the Third Crusade clearly showed Byzantium's weaknesses under the Angeloi emperors. When Richard I of England took Cyprus from its ruler, Isaac Komnenos, he refused to give it back to the empire. And when Frederick Barbarossa conquered Iconium, Isaac failed to take action. The Angeloi emperors' internal policy was marked by wasting public money and poor financial management. Byzantine authority was severely weakened, and the growing power vacuum in the center of the empire encouraged it to break into smaller pieces. There is evidence that some Komnenian heirs had set up a semi-independent state in Trebizond before 1204 AD. Historians say that the Angeloi dynasty, though Greek in origin, "hastened the ruin of the Empire, already weakened from outside and disunited within."

The Fourth Crusade and its Impact

In 1198 AD, Pope Innocent III started talking about a new crusade. The goal of this crusade was to conquer Egypt, which was then the center of Muslim power in the Holy Land. The Crusader army that arrived in Venice in the summer of 1202 AD was smaller than expected. They didn't have enough money to pay the Venetians, whose fleet was hired to take them to Egypt. Venetian policy, under the old and blind but still ambitious Doge Enrico Dandolo, might have been different from the Pope's and the Crusaders'. This was because Venice had strong trade ties with Egypt. The Crusaders agreed to help the Venetians capture the Christian port of Zara in Dalmatia instead of paying. Zara was a city loyal to Venice that had rebelled and put itself under Hungary's protection in 1186 AD. The city fell in November 1202 AD after a short siege. The Pope, who knew about the plan (and whose veto was ignored), was hesitant to risk the Crusade. He gave the Crusaders conditional forgiveness, but not the Venetians.

After the death of Theobald III, the leadership of the Crusade went to Boniface of Montferrat. Boniface was a friend of Philip of Swabia, and both had married into the Byzantine imperial family. In fact, Philip's brother-in-law, Alexios Angelos, the son of the deposed and blinded emperor Isaac II Angelos, had appeared in Europe seeking help and had contacted the Crusaders. Alexios offered to reunite the Byzantine church with Rome, pay the Crusaders 200,000 silver marks, and join the Crusade with 200,000 silver marks and all the supplies they needed to get to Egypt. The Pope knew about a plan to divert the Crusade to Constantinople and forbade any attack on the city. But the Pope's letter arrived after the fleets had left Zara.

Alexios III made no preparations to defend the city. So, when the Venetian fleet entered the waters of Constantinople in June 1203 AD, they met little resistance. In the summer of 1203 AD, Alexios III fled. Alexios Angelos was then made emperor as Alexios IV, along with his blind father Isaac. The Pope scolded the Crusader leaders and ordered them to go immediately to the Holy Land.

In late November 1203 AD, Alexios IV announced that his promises were hard to keep because the empire was short on money. He had paid about half of the promised amount and couldn't pay for the Venetians' fleet. So, the Crusaders declared war on him. Meanwhile, opposition to Alexios IV grew within the city. On January 25, 1204 AD, one of his courtiers, Alexios Doukas, killed him and took the throne as Alexios V. Isaac died soon after, likely from natural causes. The Crusaders and Venetians, angered by the murder of their supposed supporter, prepared to attack the Byzantine capital. They decided that 12 electors (six Venetians and six Crusaders) should choose a Latin emperor for the new "Romania."

The Crusaders took the city again on April 13, 1204 AD. Constantinople was then looted and massacred by the soldiers for three days. Many priceless icons, relics, and other objects later appeared in Western Europe, a large number in Venice. When order was restored, the Crusaders and Venetians carried out their agreement. Baldwin of Flanders was elected Emperor of a new Latin Empire, and the Venetian Thomas Morosini was chosen as Patriarch. The lands divided among the leaders included most of the former Byzantine territories. However, resistance continued through the Byzantine remnants in Nicaea, Trebizond, and Epirus.

The Final Fall

Empire in Exile

After Constantinople was sacked by Latin Crusaders in 1204 AD, two Byzantine successor states were formed: the Empire of Nicaea and the Despotate of Epirus. A third, the Empire of Trebizond, was created a few weeks before the sack of Constantinople. Of the three, Epirus and Nicaea had the best chance of taking back Constantinople. The Nicaean Empire struggled to survive for the next few decades. By the mid-1200s, it had lost much of southern Anatolia. The weakening of the Seljuk Sultanate after the Mongol Invasion in 1242–43 AD allowed many Turkish groups to set up their own small states in Anatolia. This weakened Byzantine control over Asia Minor. In time, one of these Turkish leaders, Osman I, created an empire that would eventually conquer Byzantium. However, the Mongol Invasion also gave Nicaea a temporary break from Seljuk attacks, allowing it to focus on the Latin Empire to the north.

Recapturing Constantinople

The Empire of Nicaea, founded by the Laskaris family, managed to reclaim Constantinople from the Latins in 1261 AD and defeat Epirus. This led to a short period of Byzantine recovery under Michael VIII Palaiologos. But the empire, damaged by war, was not ready to deal with the enemies that now surrounded it. To continue his campaigns against the Latins, Michael moved troops from Asia Minor. He also placed very heavy taxes on the farmers, causing much anger. Huge building projects were completed in Constantinople to repair the damage from the Fourth Crusade. But none of these efforts helped the farmers in Asia Minor, who were suffering from raids by fanatical Turkish warriors.

Instead of holding onto his lands in Asia Minor, Michael chose to expand the empire, gaining only short-term success. To avoid another sacking of the capital by the Latins, he forced the Church to submit to Rome. This was another temporary solution for which the farmers and people of Constantinople hated Michael. The efforts of Andronikos II Palaiologos and later his grandson Andronikos III Palaiologos were Byzantium's last real attempts to bring back the empire's glory. However, Andronikos II's use of mercenaries often backfired, with one group of soldiers ravaging the countryside and increasing anger towards Constantinople.

Late Civil Wars and Ottoman Rise

Internal fighting greatly weakened the Byzantine Empire's military power in the 1300s. This included two major civil wars starting in 1321 and 1341 AD. The civil war of 1321–28 AD was led by a grandson of Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos. He was supported by powerful Byzantine nobles who often disagreed with the central government. The war was not decisive and ended with Andronikos III Palaiologos becoming co-emperor with his grandfather. However, the civil war allowed the Ottoman Turks to make big gains in Anatolia and set up their capital in Bursa, not far from Constantinople. After the first conflict, Andronikos III removed his grandfather from the throne and became the sole emperor.

After Andronikos III died in 1341 AD, another civil war broke out, lasting until 1347 AD. Andronikos III left his six-year-old son under the care of Anne of Savoy. The real leader of the Byzantine Empire, John Cantacuzenus, was a close friend of the dead emperor and a very rich landowner. He wanted to become regent instead. He failed, but he was declared emperor in Thrace. This conflict was largely a class struggle, with the wealthy and powerful supporting Cantacuzenus and the poorer people supporting the empress regent. In fact, when nobles in 1342 AD suggested that the city of Thessalonica be given to Cantacuzenus, anti-aristocrats seized the city and governed it until 1350 AD.

The civil war allowed the rising Serbian Empire to take advantage of the Byzantine Empire. The Serbian king Stefan Uroš IV Dušan made significant land gains in Byzantine Macedonia in 1345 AD and conquered large parts of Thessaly and Epirus in 1348 AD. However, Dušan died in 1355 AD, along with his dream of a Greek-Serbian empire.

Cantacuzenus conquered Constantinople in 1347 AD and ended the civil war. To secure his power, Cantacuzenus hired Turkish mercenaries left over from the civil war to use in ongoing fights against his opponents. While these mercenaries were somewhat useful, in 1354 AD, they seized Gallipoli from the Byzantines. In the same year, the rogue mercenaries were defeated by Western Crusaders. Turkish armies would eventually control much of the territory once held by the Byzantine Empire. These two major civil wars severely weakened the Byzantine Empire's military strength and allowed its enemies to make big gains into Byzantine territory. Later, a smaller conflict arose from 1373–79 AD, and a revolt in 1390 AD. The Byzantine Empire was becoming surrounded by the Ottoman advance.

The Ottoman Rise and Constantinople's Fall

Things got worse for Byzantium when, during the civil war, an earthquake at Gallipoli in 1354 AD destroyed the fort. This allowed the Turks to cross into Europe the very next day. By the time the Byzantine civil war ended, the Ottomans had defeated the Serbians and made them their subjects. After the Battle of Kosovo, much of the Balkans came under Ottoman control.

The emperors appealed to the West for help. But the Pope would only consider sending aid if the Eastern Orthodox Church reunited with the Church of Rome. Church unity was considered, and sometimes even declared by imperial order. But the Eastern Orthodox people and clergy strongly disliked Roman authority and the Latin Church. Some Western troops arrived to help defend Constantinople, but most Western rulers, busy with their own problems, did nothing as the Ottomans slowly took over the remaining Byzantine territories.

By this stage, Constantinople was underpopulated and falling apart. The city's population had dropped so much that it was now little more than a group of villages separated by fields. On April 2, 1453 AD, the Sultan's army of about 80,000 men and many irregular soldiers laid siege to the city. Despite a desperate last-ditch defense by the greatly outnumbered Christian forces (about 7,000 men, 2,000 of whom were foreign), Constantinople finally fell to the Ottomans after a two-month siege on May 29, 1453 AD. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, was last seen taking off his imperial clothes and fighting hand-to-hand after the city's walls were breached.

Aftermath and Legacy

By the time Constantinople fell, the only remaining Byzantine territory was the Despotate of the Morea. This area was ruled by brothers of the last Emperor and continued as a state that paid tribute to the Ottomans. Poor rule, failure to pay the yearly tribute, and a revolt against the Ottomans finally led to Mehmed II's invasion of Morea in May 1460 AD. He conquered the entire Despotate by that summer. The Empire of Trebizond, which had split from the Byzantine Empire in 1204 AD, became the last remnant and last actual successor state to the Byzantine Empire. Efforts by Emperor David of Trebizond to get European powers to join an anti-Ottoman crusade led to war between the Ottomans and Trebizond in the summer of 1461 AD. After a month-long siege, David surrendered the city of Trebizond on August 14, 1461 AD. With the fall of Trebizond, and then the Principality of Theodoro by the end of 1475 AD, the last parts of the Roman Empire were gone.

The nephew of the last Emperor, Constantine XI, named Andreas Palaeologos, inherited the title of Roman Emperor. He lived in the Morea until its fall in 1460 AD, then escaped to Rome. He lived there under the protection of the Pope for the rest of his life. He called himself "Emperor of Constantinople" and sold his right to the title to both Charles VIII of France and the Catholic Monarchs of Spain. However, no one ever used the title after Andreas's death, so he is considered the last person to hold the title of Roman Emperor. Mehmed II and the Ottoman rulers after him continued to see themselves as heirs to the Roman Empire until the Ottoman Empire ended in the early 1900s. Meanwhile, the Danubian Principalities (whose rulers also saw themselves as heirs of the Eastern Roman Emperors) welcomed Orthodox refugees, including some Byzantine nobles.

Vlachs and Romanians speak a Romance language and see themselves as descendants of the ancient Romans who conquered southeastern Europe. Vlach is a name given to them by others, as the Vlachs used various words from "romanus" to refer to themselves. All Balkan countries were influenced by the Vlachs from early medieval times. Today, the Vlachs do not have their own country.

After the fall of Constantinople, the role of the emperor as a protector of Eastern Orthodoxy was claimed by Ivan III of Russia. He had married Andreas's sister, Sophia Paleologue. Her grandson, Ivan IV, would become the first Tsar of Russia. "Tsar" means "Caesar" and was a term traditionally used by Slavs for the Byzantine Emperors. Their successors supported the idea that Moscow was the rightful heir to Rome and Constantinople. The idea of the Russian Empire as the new "Third Rome" continued until its end with the Russian Revolution of 1917.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del Imperio bizantino para niños

In Spanish: Historia del Imperio bizantino para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |