Julian (emperor) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Julian |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Augustus | 3 November 361 – 26 June 363 (proclaimed in February 360) | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Constantius II | ||||||||

| Successor | Jovian | ||||||||

| Caesar | 6 November 355 – 360 | ||||||||

| Born | 331 Constantinople, Roman Empire |

||||||||

| Died | 26 June 363 (aged 31–32) Samarra, Mesopotamia, Sassanid Empire |

||||||||

| Burial | Tarsus, then Church of the Holy Apostles | ||||||||

| Spouse | Helena (m. 355, died 360) | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Dynasty | Constantinian | ||||||||

| Father | Julius Constantius | ||||||||

| Mother | Basilina | ||||||||

| Religion |

|

||||||||

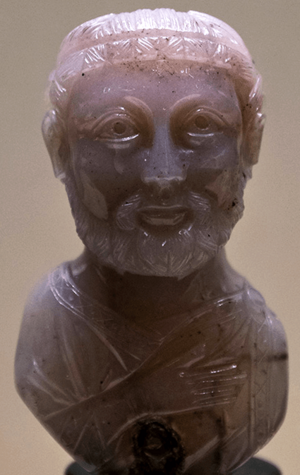

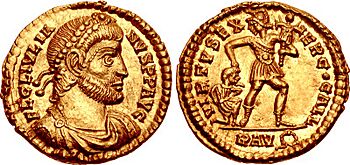

Julian (born in 331 – died June 26, 363) was a Roman leader. He was a Caesar (a junior emperor) in the western part of the Roman Empire from 355 to 360. Then, he became the full Roman emperor from 361 to 363. He was also a talented philosopher and writer.

Julian is often called Julian the Apostate by Christians. This is because he turned away from Christianity and instead promoted Neoplatonic Hellenism, which was the traditional Greek and Roman religion. He is also sometimes known as Julian the Philosopher because of his deep interest in learning.

Julian was a nephew of Constantine the Great, a famous Roman emperor. Julian was one of the few family members who survived the difficult times and conflicts during the rule of his cousin, Constantius II. Julian became an orphan when his father was killed in 337. He spent much of his life under Constantius's watchful eye. However, Constantius allowed Julian to get a good education in the Greek-speaking East. This made Julian unusually well-read for an emperor of his time.

In 355, Constantius II called Julian to his court and made him a ruler in Gaul. Even though Julian had no experience, he was surprisingly successful. He defeated Germanic invaders along the Rhine river. He also helped the damaged provinces become strong again. In 360, his soldiers in Lutetia (now Paris) declared him emperor. This started a civil war with Constantius. But Constantius died before they could fight, and he supposedly named Julian as his successor.

In 363, Julian started a big military campaign against the Sasanian Empire (Persia). The campaign began well, with a victory outside Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia. However, he did not try to capture the capital city. Julian moved deeper into Persia, but his army soon had problems getting supplies. He had to retreat north while Persian fighters constantly attacked them. During the Battle of Samarra, Julian was badly wounded and died.

Jovian, a high-ranking officer, became emperor after Julian. Jovian had to give up some Roman land to save the trapped Roman army. Julian and Jovian were the last emperors to rule the entire Roman Empire alone. After them, the empire was permanently split into a Western and Eastern part.

Julian was the last non-Christian ruler of the Roman Empire. He believed that Rome needed to go back to its old values and traditions to survive. He tried to make the government smaller and less corrupt. He also tried to bring back traditional Roman religious practices instead of Christianity. He even tried to rebuild a Third Temple in Jerusalem. This was probably meant to weaken Christianity. Julian also stopped Christians from teaching and learning classical texts.

Early Life of Julian

Julian, whose full name was Flavius Claudius Julianus, was born in Constantinople around 331. He was part of the emperor's family. His father, Julius Constantius, was the younger half-brother of Emperor Constantine I. Julian's mother, Basilina, was a noblewoman. She died shortly after he was born. Julian grew up in Constantinople and loved the city. He likely spoke Greek as his first language. Since his uncle Constantine was the first Christian emperor, Julian was raised as a Christian.

After Constantine died in 337, there was a lot of trouble. Julian's cousin, Constantius II, seemed to have ordered the killing of most of Julian's close relatives. This was to make sure he and his brothers stayed in power. Only Constantius, his brothers Constantine II and Constans I, and their cousins Julian and Constantius Gallus (Julian's half-brother) survived. Constantius II, Constans I, and Constantine II became joint emperors. Julian and Gallus were kept away from public life. They were closely watched and given a Christian education. They were probably saved because they were so young.

Julian first grew up in Bithynia with his grandmother. At age seven, he was looked after by Eusebius, a Christian bishop. He was taught by Mardonius, a Gothic eunuch, whom Julian later spoke of fondly. After Eusebius died in 342, Julian and Gallus moved to an imperial estate in Cappadocia. There, Julian met Christian bishop George of Cappadocia, who let him read classical books. When he was 18, he was allowed to live in Constantinople and Nicomedia. He became a lector, a small role in the Christian church. His later writings show he knew the Bible well, likely from this time.

Julian changed from Christianity to paganism around age 20. He later wrote that he spent 20 years as a Christian and 12 years following the "true way" of Helios (the sun god). Julian began studying Neoplatonism in Asia Minor in 351. He first studied with Aedesius, then with Aedesius's student Eusebius of Myndus. Eusebius warned Julian about magic, but Julian was interested in Maximus of Ephesus, who practiced a mystical form of Neoplatonic theurgy (magic rituals). Julian left Eusebius to study with Maximus.

Constantine II died in 340 while attacking his brother Constans. Constans then died in 350 fighting against a rebel named Magnentius. This left Constantius II as the only emperor. He needed help, so in 351, he made Julian's half-brother, Gallus, a caesar in the East. Constantius II then focused on Magnentius, whom he defeated. In 354, Gallus, who had ruled harshly, was executed.

Julian was called to Constantius's court in Mediolanum (Milan) in 354. He was held for a year because he was suspected of plotting against the emperor. But he was cleared, partly because Empress Eusebia helped him. He was then allowed to study in Athens. There, Julian met Gregory of Nazianzus and Basil the Great, who later became important Christian figures. During this time, Julian also joined the Eleusinian Mysteries, a secret religious group he later tried to bring back.

Julian as Caesar in Gaul

After dealing with rebellions, Emperor Constantius needed someone to represent him in Gaul. In 355, Julian was called to Milan. On November 6, he was made Caesar of the West. He also married Constantius's sister, Helena. Constantius wanted Julian to be more of a symbol than an active ruler. So, he sent Julian to Gaul with a small group of helpers, thinking his own officials there would control Julian.

Julian was at first hesitant to leave his studies for war and politics. But he soon took every chance to get involved in Gaul's affairs. In the next few years, he learned how to lead an army. He fought many battles against Germanic tribes who had settled on both sides of the Rhine River.

Fighting Germanic Tribes

In his first campaign in 356, Julian led his army to the Rhine. He fought the local tribes and took back several towns that the Franks had captured, including Colonia Agrippina (Cologne). After this success, he went back to Gaul for the winter. He spread his forces out to protect different towns. He chose the small town of Senon near Verdun to wait for spring. This was a mistake. A large group of Franks surrounded the town, and Julian was trapped for months. His general Marcellus finally lifted the siege. Julian and Marcellus did not get along well. Constantius accepted Julian's report and replaced Marcellus with Severus.

The next year, Constantius planned a joint operation to take back control of the Rhine. From the south, his general Barbatio was to march north with 25,000 soldiers. Julian, with 13,000 troops, would move east. However, Julian was delayed by an attack on Lugdunum (Lyon). This left Barbatio alone in Alamanni territory, so he had to retreat. The planned attack against the Germanic tribes failed.

With Barbatio gone, King Chnodomarius led an Alamanni army against Julian and Severus at the Battle of Argentoratum. The Romans were greatly outnumbered. During the battle, 600 Roman horsemen deserted. But Julian used the land to his advantage, and the Romans won a huge victory. The enemy was defeated and driven into the river. King Chnodomarius was captured and sent to Constantius. Ammianus, who was there, said Julian was in charge of the battle. He also said the soldiers cheered for Julian, trying to make him Augustus, but Julian refused.

Instead of chasing the enemy across the Rhine, Julian followed the river north. At Moguntiacum (Mainz), he crossed the Rhine and went deep into what is now Germany. He forced three local kingdoms to surrender. This showed the Alamanni that Rome was strong again. On his way back to winter camp in Paris, he dealt with some Franks who had taken over old forts along the river Meuse.

In 358, Julian won more victories. He defeated the Salian Franks on the Lower Rhine and settled them in Toxandria. He also drove the Chamavi tribe back to Hamaland.

Taxes and Government

At the end of 357, Julian had gained confidence from his victory over the Alamanni. He stopped a tax increase planned by the Gallic official Florentius. Julian personally took charge of the province of Belgica Secunda. This was Julian's first time dealing with civil government. His ideas were shaped by his Greek education. This role usually belonged to the praetorian prefect. However, Florentius and Julian often disagreed about how to run Gaul.

Julian's main goal as Caesar was to drive out the barbarians who had crossed the Rhine border. He wanted to gain the support of the people, which was important for his military actions. He also wanted to show his army the benefits of Roman rule. So, Julian felt it was important to rebuild peace in the damaged cities and countryside. This is why he disagreed with Florentius about tax increases and Florentius's own corruption.

Emperor Constantius tried to keep some control over Julian. He removed Julian's close advisor Saturninius Secundus Salutius from Gaul. Julian wrote a speech called "Consolation Upon the Departure of Salutius" about this.

Rebellion in Paris

In Julian's fourth year in Gaul, the Sassanid emperor, Shapur II, invaded Mesopotamia. He captured the city of Amida. In February 360, Constantius II ordered more than half of Julian's troops from Gaul to join his army in the East. This order went directly to the military commanders, bypassing Julian.

Julian at first tried to follow the order. But the troops, especially the Petulantes, did not want to leave Gaul. They rebelled. According to the historian Zosimus, army officers spread anonymous complaints against Constantius. They also worried about Julian's future. The official Florentius was not there at the time. Julian later blamed him for the order from Constantius. Some even suggested that Constantius sent the order because he feared Julian was becoming too popular.

The troops declared Julian Augustus (full emperor) in Paris. This led to a quick military effort to gain the loyalty of others. The full details are not clear, but there is some evidence that Julian might have encouraged the rebellion. If so, he quickly went back to his duties in Gaul. From June to August of that year, Julian led a successful campaign against the Attuarian Franks. In November, Julian openly used the title Augustus. He even made coins with the title, sometimes with Constantius, sometimes without. He celebrated his fifth year in Gaul with big games.

In the spring of 361, Julian led his army into the territory of the Alamanni. He captured their king, Vadomarius. Julian claimed that Vadomarius had been working with Constantius, encouraging raids on the borders of Raetia. Julian then split his forces. He sent one group to Raetia, one to northern Italy, and he led the third down the Danube River on boats. His forces took control of Illyricum, and his general, Nevitta, secured a mountain pass into Thrace. Julian was now moving towards a civil war. He later said he did this to scare Constantius and hoped they could become friends again.

However, in June, forces loyal to Constantius captured the city of Aquileia on the north Adriatic coast. This threatened to cut Julian off from his forces. Constantius's troops were marching towards him from the east. Aquileia was then surrounded by 23,000 men loyal to Julian. Julian could only wait in Naissus, the city where Constantine was born. He waited for news and wrote letters to Greek cities explaining his actions. Civil war was avoided only because Constantius died on November 3. Some sources say Constantius recognized Julian as his rightful successor in his last will.

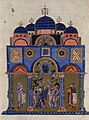

Julian's Reign as Emperor

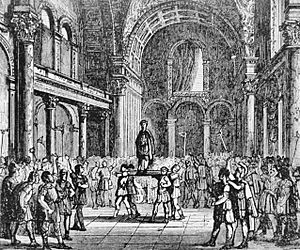

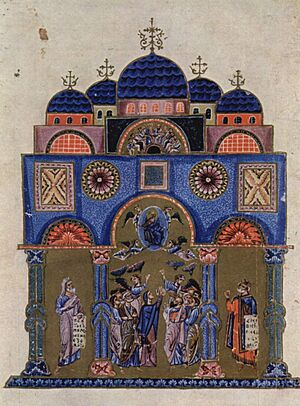

On December 11, 361, Julian entered Constantinople as the sole emperor. Even though he had rejected Christianity, his first official act was to lead Constantius's Christian burial. He escorted the body to the Church of the Holy Apostles, where it was placed next to Constantine's. This showed that he had a lawful right to the throne. He is also thought to have built Santa Costanza near Rome, a Christian site, as a tomb for his wife Helena and sister-in-law Constantina.

The new Emperor did not like how his predecessors had governed. He blamed Constantine for the problems in the government and for abandoning old traditions. He did not try to bring back the tetrarchy system started by Diocletian. He also did not want to rule as an absolute dictator. His own ideas led him to admire the reigns of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius. Julian believed an ideal ruler should be "first among equals," following the same laws as his people. So, in Constantinople, Julian often took part in Senate debates and gave speeches, acting like other members of the Senate.

He thought the royal court of previous emperors was inefficient, corrupt, and too expensive. So, he fired thousands of servants, eunuchs, and unnecessary officials. He set up the Chalcedon tribunal to investigate corruption from the previous government. Several high-ranking officials under Constantius were found guilty and executed. Julian was not present at these trials, perhaps showing he was unhappy they were necessary. He constantly tried to reduce what he saw as a costly and corrupt government.

Another result of Julian's ideas was that cities gained more power, and the imperial government became less involved in local affairs. For example, city land owned by the government was given back to the cities. City council members were forced to take back their civic duties, even if they didn't want to. Also, a gold tribute from cities, called the aurum coronarium, became voluntary instead of a required tax. Unpaid land taxes were also cancelled. This was an important reform that reduced the power of corrupt officials. Forgiving old taxes made Julian more popular and helped him collect current taxes.

While he gave more power to the cities, Julian also took more direct control himself. For example, new taxes had to be approved by him directly. Julian had a clear vision for Roman society, both politically and religiously. The chaos of the 3rd century meant the Eastern Mediterranean had become the economic center of the Empire. If cities were treated as somewhat independent local areas, it would simplify imperial government. Julian believed the government should focus on law and defending the empire's borders.

Julian replaced Constantius's political and civil officials with educated and skilled people. He also kept reliable officials like the speaker Themistius. His choices for consuls in 362 were more debated. One was Claudius Mamertinus, a respected official. The other, more surprising choice was Nevitta, Julian's trusted Frankish general. This choice showed that an emperor's power depended on the army. Julian likely chose Nevitta to keep the support of the Western army that had made him emperor.

Problems in Antioch

After five months in the capital, Julian left Constantinople in May and moved to Antioch. He arrived in mid-July and stayed for nine months. He planned to start his campaign against Persia from there in March 363. Antioch was known for its beautiful temples and a famous oracle of Apollo nearby. This might have been why he chose to live there. It was also a good place to gather troops.

His arrival on July 18 was well-received by the people of Antioch. However, it happened during the Adonia festival, which marked the death of Adonis. So, there was crying and sadness in the streets, which was not a good sign for his arrival.

Julian soon found that wealthy merchants were causing food shortages by hoarding food and selling it at high prices. He hoped the city council would fix the problem, as the situation was leading to a famine. When the council did nothing, he spoke to the city's leaders, trying to convince them to act. Thinking they would help, he turned his attention to religious matters.

He tried to bring back the ancient spring of Castalia at the temple of Apollo at Delphi. He was told that the bones of a 3rd-century bishop, Babylas, were stopping the god. So, he made a public mistake by ordering the bones removed from the temple area. This led to a huge Christian procession. Soon after, the temple was destroyed by fire. Julian suspected Christians and ordered strict investigations. He also closed the city's main Christian church. Later, investigations showed the fire was an accident.

When the city council still did not act on the food shortage, Julian stepped in. He set prices for grain and imported more from Egypt. But landowners refused to sell their grain. They claimed the harvest was so bad they needed higher prices. Julian accused them of price gouging and forced them to sell. Some historians suggest both sides had valid points.

Julian's simple lifestyle was also not popular. His people were used to an all-powerful emperor who lived in luxury. He also did not improve his image by taking part in bloody animal sacrifices.

Julian tried to deal with public criticism by writing a satire about himself called Misopogon or "Beard Hater." In it, he blamed the people of Antioch for caring more about a ruler's looks than their character.

Persian Campaign

Julian became emperor because of a military rebellion and Constantius's sudden death. This meant he had the full support of the Western army, but the Eastern army was loyal to the emperor he had fought against. To gain the Eastern army's loyalty, he needed to lead them to victory. A campaign against the Sassanid Persians offered this chance.

He planned a bold attack to capture the Sassanid capital, Ctesiphon, and secure the eastern border. The reasons for this ambitious plan are not fully clear. There was no urgent need for an invasion, as the Sassanids sent messengers hoping for peace. Julian refused their offer. Historian Ammianus says Julian wanted revenge on the Persians and sought glory.

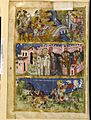

Into Enemy Lands

On March 5, 363, Julian left Antioch with about 65,000 to 90,000 soldiers. He headed north towards the Euphrates River. Along the way, small kingdoms offered help, but he refused. He ordered the Armenian King Arsaces to gather an army and wait. Julian crossed the Euphrates near Hierapolis and moved east to Carrhae. He made it seem like he would invade Persia by going down the Tigris River. He sent 30,000 soldiers under Procopius and Sebastianus further east to attack Media with Armenian forces. This was where earlier Roman campaigns had focused, and where the main Persian forces soon gathered. However, Julian's real plan was different.

He had a fleet of over 1,000 ships built at Samosata to supply his army as they marched down the Euphrates. He also had 50 pontoon ships for river crossings. Procopius and the Armenians were to march down the Tigris to meet Julian near Ctesiphon. Julian's main goal seemed to be to change the Persian ruler, by replacing King Shapur II with his brother Hormisdas.

After pretending to march further east, Julian's army turned south to Circesium at the meeting point of the Abora and the Euphrates. They arrived in early April. Passing Dura on April 6, the army made good progress. They bypassed towns after talks or besieged those that resisted. At the end of April, the Romans captured the fortress of Pirisabora. This fort guarded the canal route from the Euphrates to Ctesiphon on the Tigris. As the army marched towards the Persian capital, the Sassanids broke the dams, turning the land into marshland. This slowed the Roman army's progress.

At Ctesiphon

By mid-May, the army reached the heavily fortified Persian capital, Ctesiphon. Julian partly unloaded his fleet and had his troops ferried across the Tigris at night. The Romans won a battle against the Persians outside the city gates, driving them back into the city. However, the Persian capital was not captured. The general Victor worried about being trapped inside the city. He ordered his soldiers not to enter the open gates in pursuit of the defeated Persians. As a result, the main Persian army was still free and approaching. The Romans lacked a clear goal.

In a meeting of war leaders, Julian's generals convinced him not to siege the city. Its defenses were too strong, and Shapur would soon arrive with a large force. Julian did not want to give up what he had gained. He probably still hoped for the arrival of Procopius and Sebastianus's column. So, he set off east into Persia, ordering his fleet to be destroyed. This was a quick decision. They were on the wrong side of the Tigris with no clear way to retreat. The Persians began to attack them from a distance, burning any food in the Romans' path. Julian had not brought enough siege equipment. He found that the Persians had flooded the area behind him, forcing him to retreat. On June 16, 363, a second war council decided the best plan was to lead the army back to Roman borders. They would go north to Corduene, not through Mesopotamia.

Death of Julian

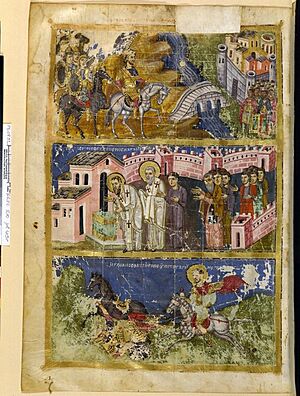

During the retreat, Julian's forces were attacked several times by Sassanid forces. In one battle on June 26, 363, the Battle of Samarra near Maranga, Julian was wounded. This happened when the Sassanid army raided his column. In his hurry to chase the retreating enemy, Julian chose speed over safety. He only took his sword and left his armor. He was wounded by a spear that reportedly went through his liver and intestines. The wound was not immediately deadly. Julian was treated by his doctor, Oribasius of Pergamum. He tried to treat the wound, possibly by cleaning it with wine and stitching the damaged intestine. On the third day, Julian had a major bleeding and died during the night.

Some Christian writers said his last words were "You have won, Galilean," meaning Jesus. As Julian wished, his body was buried outside Tarsus. Later, it was moved to Constantinople.

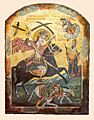

In 364, a writer named Libanius said Julian was killed by a Christian soldier from his own army. However, other historians like Ammianus Marcellinus do not support this claim. John Malalas reported that Basil of Caesarea ordered the killing. Fourteen years later, Libanius said Julian was killed by a Saracen (a Lakhmid). Julian's doctor Oribasius, who examined the wound, may have confirmed this. Later Christian historians spread the story that Saint Mercurius killed Julian.

Julian's Legacy

Julian was followed by Emperor Jovian, who ruled for a short time. Jovian brought back Christianity's special status throughout the Empire.

Libanius wrote that many cities honored Julian like a god. He said people prayed to him and their prayers were answered. However, the Roman government, which became more Christian, did not take similar actions.

A famous, but likely untrue, story says Julian's dying words were "You have won, Galilean" (meaning Jesus). This supposedly showed he knew Christianity would become the Empire's main religion after his death. This phrase is used in the 1866 poem "Hymn to Proserpine" and the 1833 Polish play The Undivine Comedy.

Julian's Tomb

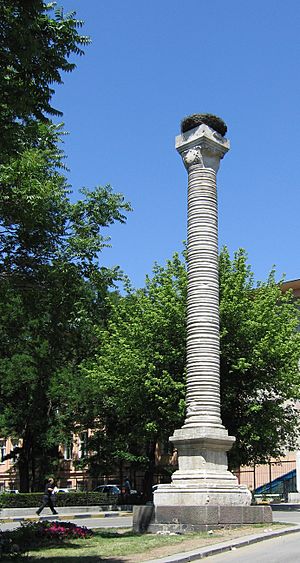

As he had asked, Julian's body was buried in Tarsus. His tomb was outside the city, across from the tomb of Maximinus Daia.

However, the writer Zonaras says that at some "later" date, Julian's body was dug up and reburied in or near the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. This is where Constantine and the rest of his family were buried. His stone coffin is listed as being in a "stoa" (a covered walkway) there by Constantine Porphyrogenitus. The church was destroyed by the Ottomans after Constantinople fell in 1453. Today, a porphyry sarcophagus, believed by some to be Julian's, is in the grounds of the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul.

Julian's Religious Beliefs

His Personal Faith

Julian's personal religion was a mix of paganism and philosophy. He saw the old myths as stories that explained deeper truths. He believed the ancient gods were different parts of a single philosophical god. His main surviving writings are To King Helios and To the Mother of the Gods. These were written as praises, not religious studies.

Julian was the last pagan ruler of the Roman Empire, so his beliefs are very interesting to historians. He learned theurgy (a type of magic ritual) from Maximus of Ephesus. His ideas were similar to the Neoplatonism of Plotinus. Some historians also think he was influenced by Mithraism, another ancient religion. Certain parts of his thinking, like organizing paganism with high priests and believing in one main god, might show Christian influence. It is hard to know for sure because many of the sources that influenced him are lost.

One idea is that Julian's paganism was very unusual. It was strongly shaped by a secret approach to Platonic philosophy called theurgy and Neoplatonism. Others argue that Julian's philosophical views were normal for an educated pagan of his time. They also say his paganism was not just philosophy; he was deeply devoted to the same gods and goddesses as other pagans.

Because of his Neoplatonist background, Julian accepted how humanity was created as described in Plato's Timaeus. Julian wrote that when Zeus was creating everything, drops of sacred blood fell from him, and from these, humans were born. He also wrote that those who could create one man and one woman could create many at once. This was different from the Christian belief that humanity came from one pair, Adam and Eve. He also argued against the single pair origin, noting how different Germans and Scythians were from Libyans and Ethiopians.

The Christian historian Socrates Scholasticus believed that Julian thought he was Alexander the Great "in another body." This was through transmigration of souls, following the teachings of Pythagoras and Plato.

Julian's diet was mostly vegetables.

Bringing Back State Paganism

After becoming emperor, Julian began a religious reform of the empire. He wanted to bring back the strength of the Roman state. He supported restoring Hellenistic polytheism (worship of many gods) as the state religion. His laws often targeted wealthy and educated Christians. His goal was not to destroy Christianity, but to remove it from the ruling classes.

He restored pagan temples that had been taken since Constantine's time. He also stopped the payments Constantine had given to Christian bishops. He removed their other special rights, like being asked about appointments or acting as private courts. He also reversed some favors given to Christians. For example, he reversed Constantine's decision that Majuma, the port of Gaza, was a separate city. Majuma had many Christians, while Gaza was mostly pagan.

On February 4, 362, Julian issued a law to guarantee freedom of religion. This law said that all religions were equal before the law. It stated that the Roman Empire should return to its original religious diversity. This meant the Roman state would not force any religion on its provinces. This law was seen as a favor to the Jews, meant to upset Christians.

Since past Roman emperors' persecution of Christians seemed to only make Christianity stronger, many of Julian's actions might have been meant to bother Christians. He wanted to stop them from organizing against the return of paganism. Julian's preference for a non-Christian view of Iamblichus's theurgy seemed to convince him that it was right to outlaw Christian worship and suppress Christian Holy Mysteries (sacraments).

In his School Edict, Julian required that all public teachers be approved by the Emperor. The state paid much of their salaries. Ammianus Marcellinus explained that this was to stop Christian teachers from using pagan texts, like the Iliad, which were central to classical education. The edict said: "If they want to learn literature, they have Luke and Mark: Let them go back to their churches and explain them." This was an attempt to reduce the influence of Christian schools. It also caused financial problems for many Christian scholars and teachers.

In his Tolerance Edict of 362, Julian ordered pagan temples to reopen. He also returned confiscated temple properties. He brought back "heretical" Christian bishops who had been punished by the Church. This showed tolerance for different religious views. But it might also have been Julian's attempt to create arguments and divisions among his Christian rivals.

Julian carefully set up a pagan leadership system to oppose the Church's hierarchy. He wanted to create a society where every part of citizens' lives was connected to the Emperor. There was no place for a separate organization like the Church's hierarchy or Christian charity.

Paganism Changes Under Julian

Julian's popularity during his short rule suggests he might have brought paganism back to the center of Roman public and private life. In his time, neither pagan nor Christian ideas fully dominated. The smartest people of the day debated which religion was better. For pagans, Rome was still mostly pagan and had not fully accepted Christianity.

Even so, Julian's short reign did not stop the spread of Christianity. The emperor's failure can be linked to the many different religious traditions and gods that paganism had. Most pagans preferred religions unique to their own culture. They also had internal disagreements that stopped them from forming one "pagan religion." The word "pagan" was just a simple term Christians used to group together all those who believed in other systems. In truth, there was no single Roman religion as we understand it today. Instead, paganism was a system of traditions that one historian called "a spongy mass of tolerance and tradition."

This system of tradition had already changed a lot by the time Julian came to power. The days of huge sacrifices honoring the gods were gone. The community festivals that involved sacrifices and feasts, which once united people, now caused divisions between Christians and pagans. City leaders did not have the money or support to hold religious festivals. Julian found that the money that used to support these events (sacred temple funds) had been taken by his uncle Constantine to support the Christian Church. Overall, Julian's short rule simply could not change the general feeling of indifference that had spread across the Empire. Christians had spoken out against sacrifice, taken money from temples, and removed priests and officials from the social and financial benefits they once had. Leading politicians and city leaders had little reason to upset things by bringing back pagan festivals. Instead, they chose a middle path, holding ceremonies and entertainment that were religiously neutral.

After seeing two emperors who supported the Church and tried to end paganism, it is understandable that pagans did not fully support Julian's idea of openly showing their devotion to many gods and rejecting Christianity. Many chose a practical approach and did not actively support Julian's public reforms. They feared a Christian return to power. However, this lack of enthusiasm forced the emperor to change key parts of pagan worship. Julian's efforts to energize the people shifted paganism from a system of tradition to a religion with some of the same features he disliked in Christianity. For example, Julian tried to create a stricter organization for priests, with higher standards for their character and service. Traditional paganism did not have this idea of priests as perfect citizens. Priests were important people with social status and money who organized and paid for festivals. But Julian's attempt to make priesthood more morally strict made paganism more like Christian morality.

This creation of a pagan order actually helped paganism and Christianity find common ground. Also, Julian's persecution of Christians, who pagans saw as just another religious group, was very unlike paganism. It turned paganism into a religion that accepted only one type of religious experience, excluding others like Christianity. By trying to compete with Christianity in this way, Julian fundamentally changed what pagan worship was. He made paganism a religion, when it had once been only a system of tradition.

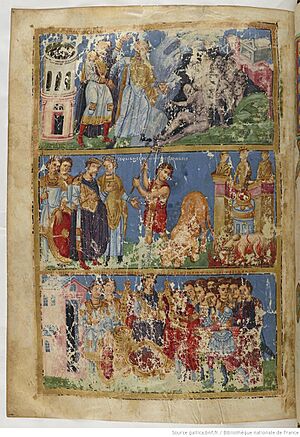

Juventinus and Maximus

Many early Christian writers were hostile towards Julian. They told stories of his supposed wickedness after his death. A sermon by Saint John Chrysostom, called On Saints Juventinus and Maximinus, tells a story about two of Julian's soldiers in Antioch. They were heard criticizing the emperor's religious policies at a party and were arrested. According to Chrysostom, the emperor tried to avoid making martyrs of those who disagreed with him. But Juventinus and Maximinus admitted they were Christians and refused to change their views. Chrysostom claims the emperor forbade anyone from contacting them, but no one obeyed. So, he had the two men executed in the middle of the night. Chrysostom encouraged his audience to visit the tomb of these martyrs.

Charity

Christian charities were open to everyone, including pagans. This meant that this part of Roman citizens' lives was controlled by the Church, not the Emperor. So, Julian planned to create a Roman charity system. He also cared about the behavior and morals of pagan priests. He hoped this would reduce pagans' reliance on Christian charity. He said: "These unholy Galileans not only feed their own poor, but ours too; welcoming them into their agapae, they attract them, as children are attracted, with cakes."

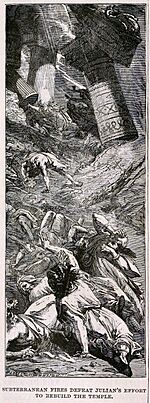

Attempt to Rebuild the Jewish Temple

In 363, just before Julian left Antioch for his campaign against Persia, he allowed Jews to rebuild their temple. This was part of his effort to oppose Christianity. The idea was that rebuilding the temple would prove wrong Jesus's prophecy about its destruction in 70 AD. Christians had used this as proof of Jesus's truth. But fires broke out and stopped the project. A personal friend of Julian's, Ammianus Marcellinus, wrote about this effort:

Julian wanted to rebuild the grand Temple in Jerusalem at great cost. He gave this task to Alypius of Antioch. Alypius worked hard, helped by the governor of the province. But terrible balls of fire kept breaking out near the foundations. They attacked the workers until they could not get close anymore. So, he gave up the attempt.

The failure to rebuild the Temple might have been caused by the Galilee earthquake of 363. In the writings of St. Gregory Nazianzen, the builders were described as "being driven against one another, as though by a furious blast of wind, and sudden heaving of the earth." Some sought safety in a church where "a flame issued forth... and stopped them." Gregory said this is "what all people nowadays report and believe." The 18th-century writer Edward Gibbon thought this was not reliable. He suggested sabotage or an accident instead. Divine intervention is a common view among Christian historians, and it was seen as proof of Jesus's divinity.

Julian's support for Jews led Jews to call him "Julian the Hellene" (meaning Greek). However, most historians believe Julian's favor towards the Jews was more an attempt to stop Christianity from growing, rather than a true liking for Judaism.

Julian's Writings

Julian wrote several works in Greek, and some of them still exist today.

| Budé No. | Date | Work Title | What it's About | Wright No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 356/7 | Praise for Constantius | Written to assure Constantius that Julian was on his side. | I |

| II | ~June 357 | Praise for Eusebia | Shows thanks for Empress Eusebia's help. | III |

| III | 357/8 | The Heroic Deeds of Constantius | Shows his support for Constantius, but also includes some criticism. | II |

| IV | 359 | Comfort After Salutius Left | Deals with his close advisor being removed from Gaul. | VIII |

| V | 361 | Letter to the Senate and People of Athens | Tries to explain why he rebelled. | – |

| VI | early 362 | Letter to Themistius the Philosopher | His response to a letter from Themistius, explaining Julian's political ideas. | – |

| VII | March 362 | To Heracleios the Cynic | Tries to correct Cynics about their religious duties. | VII |

| VIII | ~March 362 | Hymn to the Mother of the Gods | A defense of Greek culture and Roman traditions. | V |

| IX | ~May 362 | To the Uneducated Cynics | Another attack on Cynics he felt were not following their own principles. | VI |

| X | December 362 | The Caesars | A funny story about Roman emperors competing to see who was the best. It strongly criticizes Constantine. | – |

| XI | December 362 | Hymn to King Helios | Julian's attempt to describe the Roman religion as he saw it. | IV |

| XII | early 363 | Misopogon, or Beard-Hater | Written as a satire about himself, while also criticizing the people of Antioch. | – |

| – | 362/3 | Against the Galileans | A strong argument against the Christian religion. Only parts survive. | – |

| – | 362 | Fragment of a Letter to a Priest | Tries to counter the positive aspects he saw in Christianity. | – |

| – | 359–363 | Letters | Both personal and public letters from his career. | – |

| – | ? | Epigrams | A few short poems. | – |

- Budé numbers are from the Budé edition (1963 & 1964) of Julian's Opera.

- Wright numbers are from W. C. Wright's edition of Julian's works.

His religious writings contain complex philosophical ideas. The praises he wrote for Constantius are formal and detailed.

The Misopogon (or "Beard Hater") is a light-hearted story about Julian's conflict with the people of Antioch. They made fun of him for his beard and messy appearance as an emperor. The Caesars is a funny story about a competition among famous Roman emperors: Julius Caesar, Augustus, Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, and Constantine. Alexander the Great also joins the competition. This was a satirical attack on the recent emperor Constantine. Julian strongly questioned Constantine's value as both a Christian and a Roman leader.

One of his most important lost works is Against the Galileans. This book was meant to argue against the Christian religion. Only parts of this work still exist today. They were copied by Cyril of Alexandria, who used them in his own book, Contra Julianum, which argued against Julian. These copied parts do not give a full idea of the work. Cyril admitted he did not copy some of the strongest arguments.

Questions About His Writings

Julian's works have been edited and translated many times since the Renaissance. However, there are many questions about the large collection of letters said to be written by Julian. The collections of letters we have today come from many smaller collections. These smaller collections had different numbers of Julian's works in various combinations. For example, the largest collection, found in Laurentianus 58.16, has 43 manuscripts. The origins of many letters in these collections are unclear.

Joseph Bidez and François Cumont put together the different collections in 1922. They found a total of 284 items. Of these, 157 were thought to be real, and 127 were thought to be fake. This is very different from W. C. Wright's earlier collection, which has only 73 items believed to be real, along with 10 fake letters. Michael Trapp notes that Bidez and Cumont considered 16 of Wright's "real" letters to be fake. So, it is still debated which works were truly written by Julian.

The problems with Julian's writings are made worse because he was a very active writer. This means many more letters could have been passed around, even though he ruled for a short time. Julian himself mentions how many letters he had to write in a letter that is likely real. Julian's religious goals gave him even more work than the average emperor. He tried to teach his new pagan priests and dealt with unhappy Christian leaders and communities. An example of him teaching his pagan priests is found in a small piece of writing inserted into the Letter to Themistius.

Also, Julian's dislike of the Christian faith led Christian writers to strongly oppose him. For example, Gregory of Nazianzus wrote harsh criticisms against Julian. Christians likely destroyed some of Julian's works too. This Christian influence can still be seen in Wright's smaller collection of Julian's letters. She notes that some letters suddenly stop when the content becomes hostile towards Christians. She believes this is due to Christian censorship. Good examples are found in the Fragment of a letter to a Priest and the letter to High-Priest Theodorus.

Family Tree

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Family of Julian (emperor) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Emperors are shown with a rounded-corner border with their dates as Augusti, names with a thicker border appear in both sections 1: Constantine's parents and half-siblings

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

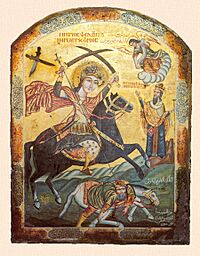

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Juliano el Apóstata para niños

In Spanish: Juliano el Apóstata para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |