History of Santa Barbara, California facts for kids

The history of Santa Barbara, California began around 13,000 years ago when the first Native Americans arrived. Later, in the 1700s, the Spanish came to settle the area and introduce Christianity. After Mexico gained independence from Spain, Santa Barbara became part of Mexico. In 1848, the United States took control of California, including Santa Barbara, after winning the Mexican–American War.

Santa Barbara then changed a lot. It went from a small town of adobe buildings to a lively place during the California Gold Rush. It became a health resort in the Victorian era, a hub for making silent films, and an oil boomtown. During World War II, it supported a military base and hospital. Today, it's a popular tourist spot with a diverse economy. The city was hit by big earthquakes in 1812 and 1925. After the 1925 quake, it was rebuilt in a beautiful Spanish Colonial style.

Contents

Ancient History of Santa Barbara

The land around the Santa Barbara Channel, including Santa Barbara and the nearby Channel Islands, has been home to the Chumash people for at least 13,000 years. The oldest human skeleton found in North America, called Arlington Springs Man, was discovered on Santa Rosa Island, about 30 miles (48 km) from Santa Barbara.

In more recent times, before Europeans arrived, the Chumash had many villages along the coast and inland. One village, on what is now Mescalitan Island, had over a thousand people in the 1500s. The Chumash were peaceful hunter-gatherers. They lived off the land's rich natural resources and traveled the ocean in special canoes called tomols. These boats were similar to those used by people in Polynesia. You can see their amazing rock art at Chumash Painted Cave. Their skilled basket weaving is displayed at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. The Chumash in Santa Barbara spoke a dialect called Barbareño. Sadly, their population decreased as Europeans settled in their lands.

Spanish Exploration and Settlement

First European Visitors

The first Europeans to see this area were part of a Spanish journey led by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo. He sailed through the Channel in 1542 and stopped near Goleta. On his way back, Cabrillo was hurt in a fight with natives on Santa Catalina Island and later died. He was buried on either San Miguel Island or Mescalitan Island.

In 1602, another Spanish explorer, Sebastián Vizcaíno, named the channel and one of the Channel Islands "Santa Barbara." He did this because he survived a big storm in the Channel on December 3, which is the day before the feast day of Saint Barbara.

Portolà Expedition Arrives

A land expedition led by Gaspar de Portolà came through in 1769. They camped on August 18 near where Laguna Street is today. There was a freshwater pond there. A large native village was nearby, which a missionary named Juan Crespi called "Laguna de la Concepcion." But Vizcaíno's earlier name, Santa Barbara, stuck. The next night, August 19, the group moved to a camp by a creek, likely Mission Creek.

Portolà's group met many friendly natives. Many lived in Syuxtun, a village behind the beach. The natives, whom the Spanish called "Canaliños" for their skilled use of canoes (tomols), gave so many gifts and played such loud music that Portolà moved his camp to get some rest. On August 20, they held the first Catholic mass in Santa Barbara, near Arroyo Burro.

Portolà's journey was the start of Spain's efforts to settle Alta California. They wanted to protect it from other European countries like the British and Russians. Also, Franciscan missions, started by Junípero Serra, aimed to convert natives to Christianity and make them loyal Spanish colonists.

Building the Presidio and Mission

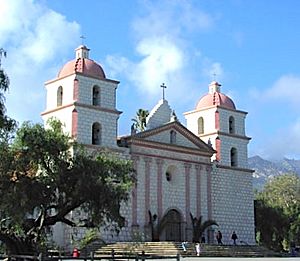

Portolà did not stay, but in 1782, soldiers led by Don Felipe de Neve came to build the Presidio of Santa Barbara. This was a military fort to protect Alta California and the missions. The Presidio was finished in 1792. Father Fermín Lasuén dedicated the nearby Mission Santa Barbara on December 4, 1786. He chose the site of a Chumash village called Tay-nay-án.

Many soldiers brought their families and settled in Santa Barbara after their service. They built adobe homes near the Presidio. Most of Santa Barbara's old families are descendants of these early settlers. Many street names, like Cota, De la Guerra, and Ortega, come from them. José Francisco Ortega was important in the Portolà expedition. He received the only Spanish land grant in Santa Barbara County in 1794, Rancho Nuestra Señora del Refugio. This ranch gave its name to Refugio State Beach. Ortega is also remembered in the name of El Capitán State Beach.

In 1793, British explorer George Vancouver anchored his ship, HMS Discovery, off West Beach. He got permission to cut wood and refill water from the Mesa bluffs.

Building the Mission continued for the rest of the century. Converting the Native Americans to Christianity was hard. By 1805, only 185 of over 500 Native Americans in Santa Barbara had been baptized. Records show that 3,997 Native Americans died between 1787 and 1841, mostly from diseases like smallpox, to which they had no immunity. By 1803, the Mission's chapel was done. By 1807, a complete village for the Native Americans was built, mostly by their own work. This village was on the Mission grounds near Constance Street.

The Spanish also built a chapel west of the Mission. This was for a group of Native Americans who lived in the Cieneguitas (swamps) area and did not want to move to the Mission. This chapel, called Cieneguitas chapel, was an adobe building with a tile roof and two bells from the King of Spain. It stood from 1803 until the 1890s. When the first adobe mission was destroyed by an earthquake in 1812, this chapel was the only place of worship left for the friars.

The 1812 Earthquake

On December 21, 1812, a very large earthquake, one of the biggest in California history, completely destroyed the first Mission and most of Santa Barbara. The quake was about magnitude 7.2. It also caused a tsunami that brought water all the way to modern-day Anapamu Street. A ship was carried half a mile up Refugio Canyon. After this disaster, the Mission priests decided to build a bigger and more detailed Mission complex. This is the one that stands today. The Franciscans started looking for building materials in 1815. They got limestone from a quarry in Hope Ranch, mixed it with seashells, and baked it in a brick kiln. While the church was ready in 1820, the bell towers were not finished until 1833.

Bouchard's Raids

The biggest military threat to Santa Barbara during the Spanish period came from Hippolyte Bouchard. He was a French privateer working for Argentina, which, like Mexico, was trying to break free from Spanish rule. Bouchard's job was to destroy Spanish ports in the Americas. He had two well-armed ships and had just destroyed Monterey, the capital of Alta California, before coming to Santa Barbara.

Bouchard's raiders first landed at Refugio Canyon on December 5, 1818. They looted and burned the Ortega family's ranch, killing cattle and horses. However, messengers from Monterey had warned the Presidio. Soldiers from the Presidio caught three of Bouchard's men and brought them back to Santa Barbara in chains. Bouchard sailed to Santa Barbara a few days later, anchoring off Milpas Street. He threatened to attack the town unless his men were returned. José de la Guerra y Noriega, the commander of the Presidio, agreed. But Bouchard didn't know he had been tricked. The town was not as heavily defended as it seemed. The hundreds of soldiers Bouchard saw through his spyglass were actually just a few dozen riding in circles, changing costumes each time they went behind some bushes. Even though Bouchard had just destroyed Monterey, he left Santa Barbara without attacking.

When Santa Barbara faced Bouchard's attack, the mission friars, following orders from Governor Pablo Vicente de Solá, used San Marcos Pass to escape. They sent the church treasures and evacuated the town's women and children to Mission Santa Inés in Solvang.

This event scared De la Guerra. He asked the viceroy for more soldiers to defend Santa Barbara. Forty-five cavalrymen, called the "Mazatlan Volunteers," were sent to De la Guerra's fort. One of these volunteers, Narciso Fabrigat, later became a civilian when Mexico gained independence. In 1843, he received the Rancho La Calera land grant. Voluntario Street is named after his group of volunteers.

Another lasting effect of Bouchard's raid was the arrival of Joseph John Chapman. He was an American sailor from Bouchard's crew who was left behind. He became the first U.S.-born person to live permanently in Spanish California. Many years later, Chapman, who married an Ortega daughter, also became the first U.S.-born permanent resident of Santa Barbara.

Mexican Rule and the American Takeover

Indian Rebellion of 1824

In 1822, Spanish rule ended, and Santa Barbara became part of independent Mexico. One important event during this time was the Indian rebellion in February 1824. The Native Americans were upset by the poor treatment from the soldiers at the Presidio, who were not being paid by the new government. The rebellion started at Mission Santa Inés and quickly spread to Mission La Purísima Concepción. In Santa Barbara, the Native Americans took control of the Mission buildings. However, Presidio soldiers quickly surrounded the buildings. Overnight, the Native Americans escaped north into Mission Canyon and over the mountains. They met up with other Native American groups in the southern San Joaquin Valley. After a battle in March and a three-month chase, the Native Americans were recaptured and brought back to Santa Barbara.

The Mexican-American War

The Mexican period in Santa Barbara ended quickly and peacefully during the Mexican–American War. This war started in May 1846 over Texas. In August, Commodore Robert F. Stockton anchored a warship in Santa Barbara harbor. He sent ten Marines to occupy the town. They raised the American flag over the city for the first time. Soon after, seeing the town was peaceful, they left. Ten cavalrymen from John C. Frémont's army replaced them. However, a group of one hundred Mexican cavalrymen chased them out. The outnumbered Americans fled on foot into Mission Canyon. They fortified a rocky ridge and resisted calls to surrender. When the Mexican force set fire to the chaparral, the Americans climbed over the mountain ridge overnight. They escaped north and eventually joined Frémont's forces in Monterey.

The most important event of the war for Santa Barbara was Frémont's return. He took a surprise route over San Marcos Pass, which was just a trail then. On December 24, 1846, during a heavy rainstorm, he led his California Battalion over the mountains. He lost many horses, mules, and cannons on the muddy slopes, but none to enemy fire. He reached the foothills near Tucker's Grove. He spent several days regrouping, camping along Mission Creek. Then he marched into Santa Barbara to capture the Presidio. He met no resistance. All the men who wanted to fight had left for Los Angeles to join the forces defending that city. On January 3, Frémont headed south, arriving in Los Angeles ten days later. The Treaty of Cahuenga, signed on January 13, 1847, ended the war in California. A year later, after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Santa Barbara officially became part of the United States.

U.S. Annexation and Growth

Gold Rush and City Changes

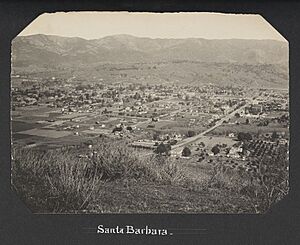

After the war, things changed fast. Gold was found in the Sierra foothills, and many people came to California hoping to get rich. Few did, but Santa Barbara started attracting settlers. Newcomers found the area charming and saw that almost anything would grow there. In 1850, California became the 31st state. Santa Barbara City and County were created right away. In 1850, the county had only 1,185 people, but that number doubled in ten years.

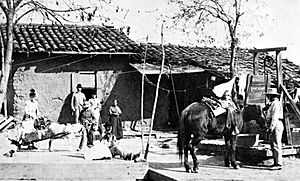

The city began to change. On April 9, 1850, Santa Barbara officially became a city and formed a town council. Settlers from the east wanted wooden houses instead of adobe. They had to import wood from Oregon because local oak trees weren't good for lumber. This led to the development of the port.

Another big change was the creation of a street grid. Before, buildings were scattered, and paths were irregular. The survey in 1851 by Salisbury Haley was a disaster. His measuring chains were broken and held together with oxhide, which stretched when damp and shrank when dry. This meant his measurements were often wrong, causing errors of up to 45 feet (14 m) across the city. Haley was supposed to create neat square blocks exactly 450 feet (137 m) on a side. A later survey found his blocks ranged from 450 to 464 feet (137 to 141 m). The misaligned lots and street problems from Haley's survey still exist today. Kinks in Mission Street and De La Guerra Street are examples. Haley also decided to lay out the streets at an angle, which still confuses people. Ironically, Haley Street, named after him, is one of the few streets that didn't need adjustments because of his errors.

The first newspaper, the Santa Barbara Gazette, started in 1855. It was half English and half Spanish because the population spoke both languages. English slowly became the main language. City Council records were in English by 1852, but Spanish was used for public records until 1870.

Lawlessness and Natural Disasters

The 1850s were a wild and violent time. The town was disrupted by rough Americans returning from the gold camps and by gangs of toughs. Some of these outlaws targeted the local Spanish population, leading to violent incidents. Outlaws like Joaquin Murrieta (the Zorro of legend) attacked travelers and citizens. A famous event was the "Battle of Arroyo Burro" in 1853, where a gang led by Jack Powers scared away about 200 citizens. Powers was eventually driven out by angry vigilantes from San Luis Obispo. His removal brought back law and order to Santa Barbara.

In 1859, Richard Henry Dana returned to Santa Barbara 24 years after his first visit. He described the changes, noting that the town still had its "repose in the golden sunlight and glorious climate." He also mentioned the "same grand surf of the great Pacific" and the "same dreamy town, and gleaming white Mission."

That same year, 1859, Santa Barbara recorded a very high temperature of 133 °F (56 °C). Birds dropped dead, cattle died, and fruit fell from trees. People fled to their adobe homes, which kept them safe from the superheated wind. In the years that followed, two other weather events greatly affected Santa Barbara. Catastrophic floods in the winter of 1861–62 caused the Goleta Slough, once open to large ships, to fill with silt and become a marsh. The disastrous drought of 1863 ended the Rancho era. The value of rangeland collapsed, cattle died or were sold, and large ranches were broken up and sold in smaller pieces for development.

Victorian Era and Modernization

The town continued to grow and slowly became less isolated after the American Civil War. The war itself had little effect on Santa Barbara. One group of cavalry joined the Union side but never fought Confederate forces. They served briefly in Arizona against Apache raids.

In 1869, Santa Barbara College, the first coeducational preparatory school in southern California, opened. Improvements to the harbor included building Stearns Wharf in 1872. This made the port more useful. Before, ships had to anchor far offshore and use small boats to load and unload cargo. In the same year, Jose Lobero built an opera house (now the Lobero Theatre), State Street was paved, and gas lamps were lit downtown.

Writer Charles Nordhoff helped make Santa Barbara a famous resort. He was hired by Southern Pacific Railroad to write about the town to attract people from the east. He called Santa Barbara the "pleasantest" spot in California, especially good for those with health problems. His book led to many travelers coming by steamship, and many stayed. The luxurious Arlington Hotel, built in 1874, housed many of them. It was destroyed by fire in 1909.

Santa Barbara's isolation ended in stages. Stearns Wharf allowed easy access by steamboat. In 1887, the railroad to Los Angeles was finished. In 1901, the railroad reached San Francisco, creating the first version of the Coast Line. Santa Barbara was finally easy to reach by land and sea. The day the first train arrived from San Francisco was also the last day the stagecoach traveled over dusty San Marcos Pass. These new connections helped Santa Barbara become the resort destination it is today. Within the city, the first electric streetcar line opened in 1896 as the need for transportation grew. By 1900, the population had reached 6,587, doubling in twenty years.

The discovery of oil changed the local economy and landscape. Oil had been known from natural seeps and used as a roof sealant for the Mission. But its value as fuel became widely known in the late 1800s. In the 1890s, the large Summerland Oil Field was found and developed. Summerland was where the world's first offshore oil well was located. Most of the oil was pumped out by 1910, but derricks stayed on the beach in Summerland until the 1920s.

Hope Ranch Development

Meanwhile, to the west, Thomas Robbins, who owned Rancho Las Positas y La Calera, died in 1860. His widow couldn't manage the 6,000-acre ranch. Thomas W. Hope bought the entire ranch in 1861. It became known as Hope Ranch. Hope had come from Ireland and worked as a cowboy in Texas. He moved west and bought 2,000 sheep, which he grazed on land leased from the Cieneguitas natives. He and his wife, Delia, lived in an adobe home.

Wool prices went up during the Civil War, making Hope rich. But he had problems. Stagecoaches and farm wagons crossed his property daily. Hope worried that continued public use might lead to a public road being built across his land. To stop this, Hope had his Native American foreman, Juan Justo, block the road and turn away all traffic. In 1873, the county surveyor began marking out a road along this path. Because of Justo's role and a war happening at the time, locals called the disputed road "the Modoc Road," which it is still called today.

Later, Hope gave a 100-foot-wide highway from his ranch to Turnpike Road, which became modern Hollister Avenue. Hope also donated land for a Catholic cemetery. Most burials were moved to Calvary Cemetery on Hope Avenue starting in 1912.

Thomas Hope never learned to read or write, but he lived well. He built the first flat racing course in California for trotters and pacers near Laguna Blanca. He also held the first hurdle races there. In 1875, Hope hired Santa Barbara's top architect, Peter J. Barber, to build a $10,000 Victorian home. It was made of redwood lumber and is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Hope died unexpectedly in 1876. He left the western half of his property to his wife. The eastern half was divided among his six children. A clause in his will said that if any daughter married a "worthless spendthrift," her share would be held in trust by his wife.

In 1887, the Southern Pacific Transportation Company built a railroad across Hope Ranch. The line was very crooked because it had to stay level. The railroad was moved to bypass Hope Ranch in 1901 when the Coast Line was finished.

Also in 1887, Delia Hope sold her half of the ranch for $200,000 in gold to the Pacific Improvement Company. This company was founded by the "Big Four" of the Southern Pacific Railroad. They had wanted Thomas Hope's land for a tourist resort. In the following decades, Hope Ranch was developed into what it is today.

Early 1900s to World War II

Silent Film Era and City Growth

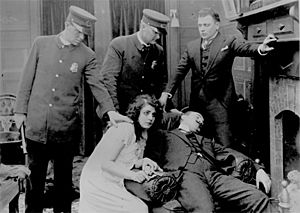

Santa Barbara was a key part of the U.S. silent film industry from 1910 to 1922. The American Film Manufacturing Company moved its western studio, Flying A Studios, to Santa Barbara in August 1912. The Santa Barbara studio became American's main location. It covered two city blocks and was the largest movie studio in the world at the time. American made about 1,200 films, but only about 100 still exist. Many were westerns, but they also made dramas and comedies about city life. Famous people like Lon Chaney, Sr. worked at Flying "A" early in their careers. In 1911, before Flying A became the biggest studio, there were 13 different film companies in Santa Barbara. The local film era ended in 1922, and studios moved south to bigger cities.

During this time, the city grew even faster. By 1920, the population reached 19,441, tripling in twenty years. A water tunnel under the mountains to Gibraltar Reservoir helped with water shortages. In the 1910s, a movement began to beautify the city, led by Bernhard Hoffmann and Pearl Chase. They wanted all new buildings to be in a Spanish Colonial style, matching the Mission. Many old buildings from the late 1800s were seen as ugly. The Lobero Theatre, built in 1924, and the first part of the Santa Barbara Natural History Museum are examples of this new style.

The 1925 Earthquake

The most destructive earthquake in Santa Barbara's history happened on June 29, 1925. It turned much of the town into rubble. The earthquake's center was offshore, but most damage came from two strong aftershocks on land. The shaking was very strong along the coast.

Only 13 or 14 people died because the quake happened early in the morning, at 6:23 a.m., before most people were out in the streets. A fire broke out after the earthquake, destroying more of the town. But U.S. Marines arrived quickly and helped control it. The earthquake, along with the architectural reform movement, helped give the town its unified Spanish look. During rebuilding, Hoffmann and Chase pushed for new structures to be in a Spanish style. The most famous of these was the County Courthouse, finished in 1929. It is called "the loveliest in the United States."

Oil Fields and World War II Impact

In 1928, oil was found at the Ellwood Oil Field near Santa Barbara. This new oil source was quickly developed. Peak production in 1930 was huge. Like at Summerland, oil derricks were built on piers into the ocean, and storage tanks dotted the cliffs. Some of this development is still there today. In 1929, the Mesa Oil Field was discovered within the city limits. It had over 100 oil derricks in the early 1930s, leading to the city's first anti-oil protest. But a local rule already allowed such development. The field was smaller than expected and failed in the late 1930s, allowing homes to be built on the Mesa.

World War II brought big changes. U.S. Marines set up camp near Goleta Point, where the University of California, Santa Barbara campus is now. The military filled in the Goleta Slough to expand the airport. The U.S. Navy took over the harbor. North of Point Conception, the Army created Camp Cooke, which later became Vandenberg Air Force Base. On February 23, 1942, a Japanese submarine fired about 25 shells at the Ellwood Oil Field. This was the first attack on a land target in the continental United States during the war. Although the gunners were bad shots and only caused about $500 damage, panic spread. Many Santa Barbara residents fled, and land values dropped. One week after the attack, on March 2, military authorities ordered the internment of Japanese Americans. About 700 people of Japanese descent gathered to be taken to Manzanar.

In 1941, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art was founded in the old Santa Barbara Post Office building.

After World War II to Today

After the war, many people who had seen Santa Barbara during the war came back to live there. The population grew by 10,000 in just five years by 1950. During this time, the University of California took over the Marine camp and turned it into a modern university. This growth brought problems with traffic, housing, and water. This led to improvements like building Highway 101 through town. Low-cost housing was built, especially on the Mesa, where oil derricks were replaced by houses. Lake Cachuma reservoir was built on the other side of the mountains, with a tunnel to bring water to residents. The city also tried to attract clean industries like aerospace and technology, instead of the oil industry. In 1959, Santa Barbara Junior College moved to its current location and was renamed Santa Barbara City College.

The oil industry moved most of its local operations offshore in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1947, the government approved offshore leases. Seismic exploration of the Channel happened in the 1950s, even though fishermen complained it killed fish. The first huge oil platforms, which are a common sight south of Santa Barbara, went up in 1958. Stearns Wharf was the main connection for oil services going out to the platforms.

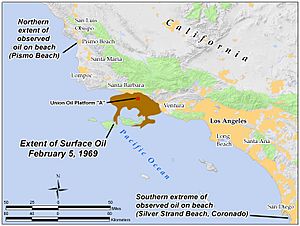

The relationship between Santa Barbara and the oil industry worsened with the disaster of January 28, 1969. A blowout on an offshore oil well released a huge amount of oil, creating a massive oil slick. It spread over hundreds of square miles of ocean, polluting shorelines, killing wildlife, and hurting the tourist industry. The anti-oil group "GOO" (Get Oil Out) formed after the spill. Oil drilling has been a sensitive topic in the area ever since. The spill also led to the passage of important environmental laws in 1970, like the National Environmental Policy Act.

The center of Santa Barbara's population moved west during this time. Areas like San Roque and Hope Ranch Annex grew. Citrus groves were cut down and replaced by homes and shops. Shopping centers like Loreto Plaza and La Cumbre Plaza developed. Between 1960 and 1970, the population of the Goleta Valley rose from 19,016 to 60,184.

By the mid-1970s, groups against uncontrolled growth became stronger. On April 8, 1975, the City Council voted to limit the city's population to 85,000 through zoning. To limit growth in nearby areas like Goleta, the city often denied water meters to new developments. This effectively stopped growth. The city and nearby areas stopped growing fast, but housing prices rose sharply.

Several big fires burned parts of Santa Barbara and the nearby mountains. In 1964, the Coyote Fire burned 67,000 acres (271 km2) and 150 homes. In 1977, the Sycamore Fire destroyed over 200 homes. The most destructive was the 1990 Painted Cave Fire. It burned over 500 homes in just hours, causing over a quarter billion dollars in damage.

Santa Barbara in the 21st Century

When voters approved connecting to state water supplies in 1991, parts of Santa Barbara, especially outlying areas, started growing again. But it was slower than in the 1950s and 1960s. While slow growth preserved the quality of life, housing became scarce, and prices soared. In 2006, only six percent of residents could afford a median-value house. As a result, many people who work in Santa Barbara commute from more affordable areas like Santa Maria and Ventura. The resulting traffic on Highway 101 is a problem planners are trying to fix.

In 2000, local billionaire Wendy McCaw bought the Santa Barbara News-Press. Years of trouble followed as the paper changed direction, becoming unpopular with employees and readers. In 2006, reporters protested when she forced the removal of stories she didn't like. The paper lost readers as McCaw seemed to turn it against its own city. The News-Press closed in 2023.

In November 2008, the Tea Fire started in Montecito. It burned 1,800 acres (7.3 km2) and destroyed 130 homes in Santa Barbara. A 98-year-old man who evacuated died. Damages were high because of the expensive homes in the area. The fire likely started from an illegal bonfire lit by young people.

Similarly, in May 2009, the Jesusita Fire burned 8,733 acres (35.3 km2) and destroyed 80 homes northwest of the city. The fire may have started from two people using a weed whacker in hot weather.

On May 19, 2015, the Santa Barbara coast was affected by the Refugio oil spill. It was caused by a broken pipeline from Plains All American Pipeline company.

From December 2017 to June 2018, the Thomas Fire burned 281,893 acres (1,140.7 km2) and destroyed over 1,000 structures in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties. It reached the edge of Santa Barbara city. Amid dry conditions and Santa Ana winds, the fire spread quickly, killing a firefighter and causing deadly mudflows in Montecito. It was the largest fire Cal Fire had dealt with since 1932.

On September 1, 2019, the dive boat MV Conception left Santa Barbara Harbor for Santa Cruz Island. While docked at the island, 33 passengers and one crew member were sleeping when the ship caught fire and sank on September 2, killing all 34.

In the mid-2010s, there were more empty stores downtown as businesses slowed. A 2015 city report found that downtown had too many tourist shops and not enough local stores. Negative views of the area's homeless population also affected business. In 2018, the city banned sitting or lying down on the first 13 blocks of State Street. The COVID-19 pandemic made the crisis worse. Many businesses closed. In response, the city closed eight blocks of State Street to cars, making it a pedestrian mall. Reaction to this change was mixed, but the street mostly stayed that way. In 2023, bike lanes were added, and cars were allowed to drive one-way only to drop off passengers at the Granada Theatre.

In 2024, the Santa Barbara Independent newspaper wrote that removing most car traffic had not fixed downtown's problems. It was still affected by homelessness and a lack of housing. That year, the city began talks with developers to build a 642-unit housing development at a Macy's location set to close in 2028. If approved, it would be one of the largest development projects in the city's history.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |