1969 Santa Barbara oil spill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Santa Barbara Oil Spill |

|

|---|---|

Platform A in 2006

|

|

| Location | Pacific Ocean; Santa Barbara Channel |

| Coordinates | 34°19′54″N 119°36′47″W / 34.33167°N 119.61306°W |

| Date | Main spill January 28 to February 7, 1969; gradually tapering off by April |

| Cause | |

| Cause | Well blowout during drilling from offshore oil platform |

| Spill characteristics | |

| Volume | 80,000 to 100,000 barrels (13,000 to 16,000 m3) |

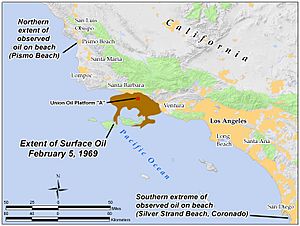

| Shoreline impacted | Southern California: Pismo Beach to the Mexican border, but concentrated near Santa Barbara |

The Santa Barbara oil spill happened in January and February 1969. It took place in the Santa Barbara Channel, close to the city of Santa Barbara in Southern California. At that time, it was the biggest oil spill in U.S. waters. Today, it is the third largest, after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon and 1989 Exxon Valdez spills. It is still the largest oil spill ever in California's waters.

The spill started from a blowout on January 28, 1969. This happened about 6 miles (10 km) from the coast. The oil came from Union Oil's Platform A in the Dos Cuadras Offshore Oil Field. Over ten days, about 80,000 to 100,000 barrels (13,000 to 16,000 m3) of crude oil spilled. It covered the Channel and beaches of Santa Barbara County. The oil reached from Goleta to Ventura. It also hit the northern shores of the four northern Channel Islands.

The spill greatly harmed ocean life. About 3,500 seabirds died. Many marine animals like dolphins, elephant seals, and sea lions were also affected. People were very angry about the spill, which was shown a lot in the news. This anger led to many new environmental laws in the U.S. These laws still help protect our environment today.

Contents

What Caused the Santa Barbara Oil Spill?

The Santa Barbara Channel has a lot of oil deep under its thick rock layers. Because of this, oil companies have been interested in the area for over 100 years. The southern coast of Santa Barbara County was where the world's first offshore oil drilling happened. This was in 1896, from piers at the Summerland Oil Field. It was only about 6 miles (10 km) from where the big spill would later happen.

Early Oil Drilling in California

Oil drilling in the Channel and nearby coast was always a debated topic. By the late 1800s, Santa Barbara was becoming a popular place for tourists. People loved its beautiful scenery, clean beaches, and perfect weather. When the Summerland oil field grew closer to Santa Barbara, some angry locals even tore down an oil rig on Miramar Beach.

Later, in 1927, oil was found west of Santa Barbara. This led to the Ellwood Oil Field. Then, in 1929, the Mesa Oil Field was found right inside the city. Oil derricks, which are tall structures used for drilling, appeared on a hilltop near the harbor. People protested, but the drilling continued because of a city rule. The derricks only left when the oil in the Mesa field ran out in the late 1930s.

Over time, new technology allowed drilling farther from shore. By the mid-1900s, drilling was happening near Seal Beach and Long Beach. This was done from man-made islands built in shallow water. Near the future spill site, the first drilling island was built in 1958. It was called Richfield Island, now Rincon Island. It was built in 45 feet (14 m) of water to get oil from the Rincon Oil Field. This island is still used for oil production today.

Scientists knew that the oil-rich rock layers under the land continued under the Channel. So, oil companies wanted to drill in deeper water. They started using seismic testing after World War II. This testing used explosions to find oil deep under the ocean floor. The explosions were loud and caused problems. They rattled windows, cracked walls, and left dead fish on the beaches. Local people and the Santa Barbara News-Press newspaper were against it. But the testing continued, though with stricter rules.

The tests showed what oil companies hoped for and what people feared. There were large oil reserves about 200 feet (60 m) deep. This depth was reachable with the new ocean-drilling technology.

However, legal battles and new laws delayed building oil platforms until the mid-1960s. The federal and state governments argued over who owned the land under the sea. In 1953, Congress passed the Submerged Lands Act. This law gave states ownership of land up to 3 nautical miles (6 km) from shore, called the tidelands. After more discussions, Santa Barbara agreed to a compromise with oil companies. They created a no-drilling zone in the Channel. It was 16 miles (26 km) long and 3 miles (5 km) wide next to the city.

Still, several large oil fields were found in state waters outside this zone. The state started giving out leases for these fields in 1957. The first offshore oil platform, Hazel, was built in 1957. Platform Hilda was built next to Hazel in 1960. Both platforms were part of the Summerland Offshore Oil Field. They could be seen from Santa Barbara on a clear day. Platform Holly, in the Ellwood Oil Field about 15 miles (24 km) west of Santa Barbara, was put in place in 1965.

Next came drilling in federal waters. In 1965, the Supreme Court decided that lands beyond the 3 miles (5 km) limit belonged to the federal government. So, the government offered parts of the Santa Barbara Channel for lease. The first lease sale happened on December 15, 1966. A group of oil companies, including Phillips and Continental, bought the first lease. They paid over $21 million to drill on about 3 square miles (8 km2) of ocean floor in the Carpinteria Offshore Oil Field.

The rig they built, Platform Hogan, was the first oil platform in federal waters off California. It started working on September 1, 1967. On February 6, 1968, 72 more leases were offered. A group including Union Oil, Gulf Oil, Texaco, and Mobil got the rights to Lease 241 in the Dos Cuadras Offshore Oil Field. Their first rig on that lease, Platform A, was set up on September 14, 1968, and drilling began.

Local people were increasingly against the oil industry from 1966 to 1968. This was despite oil companies saying their work was safe. On June 7, 1968, 2,000 US gallons (8 m3) of crude oil spilled from Phillips' new Platform Hogan. This happened even though the oil company and the Secretary of the Department of the Interior had promised it wouldn't. In November, local voters stopped the building of an onshore oil facility at Carpinteria.

How the Spill Started: Platform A Blowout

Platform A was in 188 feet (57 m) of water, about 5.8 miles (9 km) from the Summerland shore. It had 57 spots for wells to drill into the oil reservoir from different angles. At the time of the spill, it was one of twelve platforms off California. Union Oil operated two of them in the Dos Cuadras field. Four oil wells had already been drilled from Platform A but were not yet producing oil. Work on the fifth well was in progress.

On the morning of January 28, 1969, workers were drilling the fifth well, A-21. They reached its final depth of 3,479 feet (1,060 m) in just 14 days. Only the top 239 feet (73 m) of this depth had a steel conductor casing. The rest was supposed to get one after the drill bit was removed. When workers pulled the drill bit out, oil, gas, and drilling mud shot up into the rig. It splattered the workers. Some tried to attach a blowout-preventer to the pipe. But the pressure was over 1,000 pounds per square inch (7 MPa), making it impossible.

Workers were evacuated because of the risk of explosion from the gas. Finally, they tried a last-resort method. They dropped the remaining drill pipe, almost 0.5 miles (800 m) long, into the hole. Then, they crushed the top of the well pipe with "blind rams." These are huge steel blocks that slam together to stop anything from escaping. It took 13 minutes from the start of the blowout for the blind rams to be used.

Only then did workers on the rig and in nearby boats see more bubbles on the ocean surface. This was happening hundreds of feet from the rig. Plugging the well at the top had not stopped the blowout. The oil was now breaking through the ocean floor in several places.

Normally, an offshore well would have at least 300 feet (91 m) of conductor casing. This was required by federal rules then. It would also have about 870 feet (270 m) of a secondary, inner steel tube called the surface casing. Both casings are meant to stop high-pressure gas from blowing out through the sides of the well. At Well A-21, this is exactly what happened. There was not enough casing below 238 feet (73 m) to stop the huge gas pressure. Once the well was plugged at the rig, the oil and gas left the well. They ripped through the soft sandstones on the Santa Barbara Channel floor. A huge amount of oil and gas then spewed to the water surface. A thick, bubbling oil slick quickly began to grow.

Oil Spreads Across the Ocean

The bubbling on the ocean surface started 14 minutes after the blowout. It grew larger over the next 24 hours. The biggest area of bubbling was about 800 feet (200 m) east of the platform. Another smaller area was about 300 feet (100 m) west of the platform. Several smaller bubbling spots were around the platform itself. Even after the well was plugged with drilling mud the next week, these spots kept bubbling. Investigators later found that oil and gas were escaping from five different cracks on the ocean floor.

The first warning of the disaster came from Don Craggs, a Union Oil manager. He told Lieutenant George Brown of the U.S. Coast Guard about two and a half hours after the blowout. Craggs said a well had blown out but no oil was escaping. He refused help, saying the situation was under control.

The seriousness of the spill became clear the next morning. A Coast Guard helicopter took Brown and a State Fish and Game warden over the platform. They saw a large oil slick stretching for miles east, west, and south of the platform. They estimated that 75 square miles (200 km2) were covered by oil less than 24 hours after the blowout. An anonymous worker on the rig called the Santa Barbara News-Press about the blowout. The newspaper quickly confirmed it with Union Oil's main office in Los Angeles. The story was out.

John Fraser, Union Oil Vice President, told reporters the spill was small. He said it was only 1,000 to 3,000 feet (300 to 900 m) wide and would be quickly controlled. He also estimated the spill rate at 5,000 US gallons (19 m3) per day. Later estimates showed the spill rate in the first days was about 210,000 US gallons (790 m3).

Santa Barbara had a stormy winter. A big flood had happened on January 25, just three days before the blowout. A lot of fresh water was still flowing from local streams into the ocean. This water, along with the usual winds, pushed the oil slick away from the shore. For several days, it seemed Santa Barbara's beaches would be safe.

However, another huge storm hit on February 4. Winds pushed the oil slick north into Santa Barbara harbor and onto all the beaches. Booms, which are floating barriers, had been placed around the harbor and beaches. But the waves were heavy in the storm. The oil was up to 8 inches (200 mm) deep at the booms by late afternoon. That evening, the booms completely broke. By morning, the entire harbor, with about 800 boats, was covered in several inches of crude oil. All the boats were black. People were told to leave because of the risk of explosion from the gas fumes. Oil cleanup crews and the Coast Guard started using chemicals to break up the oil near the shore.

On the morning of February 5, people along the coast woke up to the smell of crude oil. They saw blackened beaches with dead and dying birds. The sound of waves was strangely quiet because of the thick oil layer. In some places, the oil on shore was 6 inches (150 mm) deep. People visited the beaches and watched in horror.

Fighting the Oil Spill

Five days after workers tried to stop Well A-21, on February 12, a research ship found something new. Three large new bubbles of gas and oil were coming from the ocean floor. Each rupture was about ten yards wide. A large oil slick was forming on the ocean surface again. An anonymous call from a rig worker again told the Santa Barbara News-Press about the new spill. This time, the oil was coming from the ocean floor, not the well. People were even angrier. It was private citizens who found the problem, and the oil company only admitted it later.

This new problem needed to be fixed on the ocean bottom. Union Oil put a large steel cap over much of the leaking area. But oil still leaked from other nearby spots. The company estimated the leak rate at up to 4,000 US gallons (15 m3) per day. The government allowed some wells to be reopened to try and stop the oil under the sea floor. They even reopened A-21. Neither method worked.

The next step was to pump oil as fast as possible from all five wells on Platform A. The idea was that this would lower the pressure in the oil reservoir and slow the leak. But this only made more oil spew from the cracks in the ocean floor. Meanwhile, cleanup efforts faced problems. Huge waves of new oil covered beaches that had been partly cleaned. Oil from the spill reached places as far as Pismo Beach, Catalina Island, and Silver Strand Beach in San Diego.

Union Oil tried to seal the cracks in the ocean floor with cement. But leaks continued. By the end of February, the flow had slowed. But oil was still seeping, though less, from cracks east and west of the platform. Leaking continued at about 30 barrels (4.8 m3) a day. It slowly decreased to between 5 to 10 barrels (0.79 to 1.59 m3) a day by May and June 1969. This slow leak continued into 1970. One last spill happened at Platform A. About 400 barrels (64 m3) leaked between December 15 and 20, 1969, from a broken pipeline.

Most beaches were cleaned in about 45 days after the first spill. However, tar balls kept washing ashore because of the ongoing leaks. Larger patches came ashore during later spills. Most beaches were open to the public by June 1. Some rocky areas were not cleaned until around August 15. But oil continued to collect and wash up. On August 26, the harbor was so full of oil that it had to be closed again. Cleanup crews spread straw from boats to gather the oil, just like they had six months before. Oil from the spill was still seen in the ocean in 1970.

President Nixon Visits the Spill Site

On March 21, President Richard Nixon came to Santa Barbara to see the spill and cleanup. He flew over the Santa Barbara Channel, Platform A, and the polluted beaches. He landed in Santa Barbara and spoke to residents. He promised to handle environmental problems better. He told the crowd, "the Santa Barbara incident has frankly touched the conscience of the American people." He also said he would consider stopping all offshore drilling. He told reporters that the Department of the Interior had made the no-drilling zone larger. They also turned the old zone into a permanent nature preserve.

However, on April 1, the drilling ban was lifted. Drilling was allowed to continue on five leases in the channel, but with stricter rules. Local residents became even angrier after this change.

After trying and failing in court to stop more oil drilling, the Department of the Interior gave permission to Sun Oil on August 15. They could build Platform Hillhouse next to Union's Platform A. Protesters bothered the convoy bringing the platform from the Oakland shipyard. The group Get Oil Out! (GOO!) held a "fish-in" with boats and helicopters at the planned platform site. They refused to move until the Supreme Court answered their appeal. Then, the crane lifting the platform dropped it. Platform Hillhouse fell over in the water, upside down.

While this was happening, the Supreme Court denied the appeal. This allowed Sun Oil to continue, even with their platform floating upside down. This was a strange and upsetting sight for locals who hoped the spill would make oil accidents less likely. By November 26, Hillhouse was installed correctly. Platform C, the last of the four platforms in the Dos Cuadras field, was built in 1977.

What Happened After the Spill?

The Santa Barbara oil spill had immediate and dramatic effects on the environment.

Impact on Animals and Nature

At least 3,686 birds died. This was only the number counted; many more died unseen. Some marine mammals, like sea lions and elephant seals, also died. The exact number is not known. The spill's effects on other living things varied. Fish populations seemed okay in the long run. But data from 1969 showed fewer fish of some types. Scientists were not sure if this was directly from the oil spill. Other things, like water temperature or an El Niño year, could have played a role. Animals living between the high and low tide lines, like barnacles, died in large numbers. In some areas, 80 to 90 percent of them died.

Overall, the long-term environmental effects of the spill seemed small. A study suggested a few reasons why there wasn't more damage to ocean life, except for birds and intertidal animals. First, creatures in the area might be used to oil in the water. This is because natural oil seeps have been there for thousands of years. The area around Coal Oil Point has one of the most active natural underwater oil seeps in the world. Second, there might be more oil-eating bacteria in the water because oil is always present. Third, the spill happened between two big storms. The storms broke up the oil, spreading it faster than in many other spills. Also, the dirt from freshwater runoff helped the oil sink quickly. Fourth, Santa Barbara Channel crude oil is heavy. It doesn't dissolve much in water and sinks easily. So, fish and other animals were exposed to the oil for a shorter time. This was different from other spills, like the 1967 Torrey Canyon spill. In that spill, the oil was lighter and stayed in the water longer.

Reports that large sea mammals were mostly unharmed were contradicted by a story in Life magazine. In late May 1969, reporters visited San Miguel Island. This island is known for its colonies of elephant seals and sea lions. The team counted over 100 dead animals on the beach they visited. The beach was still black with oil.

Money Matters: Economic Impact

The economic effects of the spill were worst in 1969. All commercial fishing stopped in the affected area. Tourism dropped sharply. Most ocean-related businesses were hurt. Property damage along the shoreline was also significant. The storms had washed oil beyond the normal high-tide line. Both government groups and private people filed lawsuits against Union Oil to get money for damages. These lawsuits were settled within about five years. The City of Santa Barbara received $4 million in 1974 for damages. Owners of hotels, beachfront homes, and other damaged places received $6.5 million. Commercial fishing businesses got $1.3 million for their losses. Cities, the state, and Santa Barbara County settled for a total of $9.5 million.

New Rules for Protecting the Environment

The Santa Barbara oil spill was not the only event that created the modern environmental movement in the United States. But it was one of the most important and visible events. It led to big changes like the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It also helped pass laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Clean Water Act. In California, it led to the California Coastal Commission and the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

During the 1960s, people became more aware of pollution. This started with Rachel Carson's 1962 book Silent Spring. Other events included the Water Quality Act, the ban on DDT, and the creation of the National Wilderness Preservation System. There was also the 1967 Torrey Canyon tanker accident, which harmed coasts in England and France. And the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio, caught fire. At the time, the Santa Barbara spill was the largest oil spill in U.S. waters. It happened during a big fight between locals and the oil company. This made the issue even more public and made the anti-oil cause seem right to many more people. In the years after the spill, more environmental laws were passed than ever before in U.S. history.

The spill was the first test for the new National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan. President Lyndon Johnson signed this plan into law in 1968. Officials from the Federal Water Pollution Control Administration came to Santa Barbara. They oversaw the cleanup and the effort to plug the well.

Local groups formed after the spill. These included Get Oil Out! (GOO), which started on the first day of the disaster. Also, the Environmental Defense Center and the Community Environmental Council were created. Plus, people like Rod Nash, Garrett Hardin, and environmental lawyer Marc McGinnes started the first college program in Environmental Studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara. A California ballot initiative created the powerful California Coastal Commission. This group watches over all activities in the coastal zone. This zone is 3 nautical miles (6 km) from the shoreline and extends inland.

How Laws Changed After the Spill

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) completely changed how things worked. It required that all projects by any federal government agency be checked for their possible bad effects on the environment. This had to happen before they were approved. It also included a time for the public to give their opinions. This applied to plans for new drilling platforms in offshore oil leases.

Protecting Our Coasts: Drilling Bans

The California State Lands Commission has not given out any new leases for offshore drilling in its area since 1969. This area goes out to the 3 nautical miles (6 km) limit. However, existing operations, like at Platform Holly on the Ellwood field and Rincon Island on the Rincon field, have been allowed to continue. A plan to drill into the state-controlled zone from an existing platform outside it was rejected in 2009.

Drilling beyond the three-mile limit, in federal waters, has been more complex. Oil production from existing leases has mostly continued since the spill. New drilling from existing platforms within lease boundaries has also been allowed. But no new leases have been given out in federal waters since 1981.

In 1981, Congress put a temporary stop, called a moratorium, on new offshore oil leasing. This stop lasted until 2008.

Some leases bought in the 1960s were not developed until much later. Even with the moratorium on new leases, Exxon installed Platforms Harmony and Heritage in the Santa Barbara Channel in 1989. These platforms were in over 1,000 feet (300 m) of water. They completed the development of their Santa Ynez Unit. Several federal leases are still undeveloped.

The First Earth Day

About three months before Earth Day, Santa Barbara celebrated Environmental Rights Day on January 28, 1970. This was the first anniversary of the oil blowout. Here, the Declaration of Environmental Rights was read. The people who organized this event worked with Congressman Pete McCloskey to create the National Environmental Policy Act. Many important people spoke at the Environmental Rights Day conference. They supported the Declaration of Environmental Rights. Denis Hayes, an organizer of the first Earth Day, said this was the first big crowd he spoke to that cared so much about environmental issues. He thought then that it might be the start of a movement.

The spill's aftermath inspired then-Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin to organize "Earth Day". He gathered about 20 million people to learn about environmental issues on April 22, 1970. He did this with the help of Denis Hayes and U.S. Representative Pete McCloskey.

Santa Barbara Oil Spill Today

Platform A is still in the Santa Barbara Channel. Its three sister platforms, B, C, and Hillhouse, are also there. They are still pumping oil from the mostly used-up field. As of 2010, the Dos Cuadras Field has produced 260 million barrels of oil. Experts estimated in 2010 that 11,400,000 barrels (1,810,000 m3) of oil remain in the field and can be recovered with today's technology.

The company that currently operates Platform A and the other three platforms in the Dos Cuadras field is DCOR LLC. They are a private firm from Ventura, California. They bought Platform A from Plains Exploration & Production in 2005. DCOR is the fourth company to run the platform since Unocal sold its Santa Barbara Channel operations in 1996.

Images for kids

-

President Richard Nixon visiting the beach on March 21, 1969

-

Colony of marine mammals (elephant seals, sea lions) at western tip of San Miguel Island, 40 years after the spill. This colony was affected by the oil spill; many of these animals were oiled, and an unknown number died.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |