Manzanar facts for kids

|

Manzanar War Relocation Center

|

|

A hot windstorm brings dust from the surrounding desert, July 3, 1942

|

|

| Location | Inyo County, California |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Independence, California |

| Area | 814 acres (329 ha) |

| Built | 1942 |

| Visitation | 97,382 (2019) |

| Website | Manzanar National Historic Site |

| NRHP reference No. | 76000484 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | July 30, 1976 |

| Designated NHL | February 4, 1985 |

| Designated NHS | March 3, 1992 |

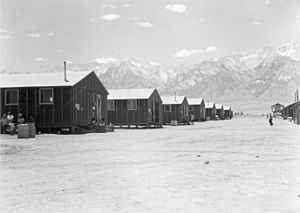

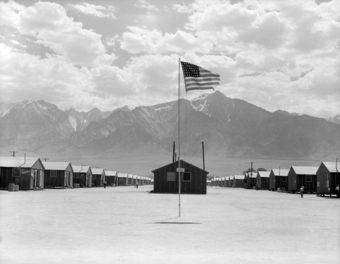

Manzanar was one of ten American concentration camps where over 120,000 Japanese Americans were held during World War II. This happened from March 1942 to November 1945. Even though it was one of the smaller camps, it held more than 10,000 people at its busiest time.

Manzanar is located at the base of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California's Owens Valley. It is between the towns of Lone Pine and Independence. This spot is about 230 miles (370 km) north of Los Angeles. The word "Manzanar" means "apple orchard" in Spanish.

Today, the Manzanar National Historic Site protects this important place. It helps us remember the history of Japanese American imprisonment in the United States. The National Park Service says it's the best-preserved of the ten former camp sites.

The first Japanese Americans arrived at Manzanar in March 1942. This was just one month after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. These first arrivals helped build the camp where their families would live. Manzanar operated as a camp from 1942 to 1945.

Since the camp closed in 1945, former prisoners and others have worked to protect Manzanar. They wanted it to become a National Historic Site. This helps make sure the history of the site and the stories of those held there are remembered. The main focus is the Japanese American imprisonment era. The site also teaches about the old town of Manzanar, its ranching past, and the Owens Valley Paiute who lived there. It also explains how water shaped the history of the Owens Valley.

Contents

What Was Manzanar Before the Camp?

Manzanar was first home to Indigenous Americans almost 10,000 years ago. About 1,500 years ago, the Owens Valley Paiute people settled there. They lived across the Owens Valley.

When European American settlers arrived in the mid-1800s, they found many Paiute villages. John Shepherd was one of the first new settlers. He started a ranch in 1864. With help from Owens Valley Paiute workers, his ranch grew very large.

In 1905, George Chaffey bought Shepherd's ranch. He divided the land and started the town of Manzanar in 1910. The town grew quickly, reaching almost 200 people by 1911. They built an irrigation system and planted many fruit trees. By 1920, Manzanar had homes, a school, a town hall, and a general store. There were also thousands of acres of fruit trees and other crops.

How Water Changed Manzanar's History

The City of Los Angeles began buying water rights in the Owens Valley in 1905. In 1913, Los Angeles finished building its 233-mile (375 km) Los Angeles Aqueduct. During dry years, Los Angeles took all the water. This left Owens Valley ranchers without water for their farms.

Without water, ranchers had to leave their land and communities. This included the town of Manzanar, which was empty by 1929. Manzanar stayed empty until the United States Army rented the land. This was to create the Manzanar War Relocation Center.

Why Were People Sent to Manzanar?

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the U.S. government worried about people of Japanese descent. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) arrested many Japanese men. Many people in California were concerned about potential actions by Japanese Americans.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order allowed military commanders to create special areas and remove "any or all persons" from them. It also allowed the building of "relocation centers" to hold those who were removed.

This order led to the forced relocation of over 120,000 Japanese Americans. Two-thirds of them were born in the U.S. and were American citizens. The others were prevented from becoming citizens by law. More than 110,000 people were held in ten camps far from the coast.

Manzanar was the first of these ten camps. It started taking people in March 1942. At first, it was a temporary "reception center." It was called the Owens Valley Reception Center until May 1942. The U.S. Army's Wartime Civilian Control Administration (WCCA) ran it.

How Manzanar Became a Camp

The first director of the camp was Calvin E. Triggs. He had worked for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a government program. Many of his staff also came from the WPA. They used their experience to build things like guard towers and spotlights.

The Owens Valley Reception Center became the "Manzanar War Relocation Center" on June 1, 1942. The first Japanese Americans to arrive were volunteers. They helped build the camp. By mid-April, up to 1,000 Japanese Americans arrived daily. By July, the camp's population was almost 10,000.

About 90 percent of the people held at Manzanar were from the Los Angeles area. Others came from Stockton, California, and Bainbridge Island, Washington. Many were farmers and fishermen. At its busiest, Manzanar held 10,046 people. A total of 11,070 people were held there over time.

Life Inside the Camp

People who were forced to leave their homes faced difficult conditions at Manzanar. They had little privacy and had to wait in long lines for meals, bathrooms, and laundry. Each camp was meant to be self-sufficient. Manzanar had its own services like a newspaper, shops, and a hospital. Some people raised chickens, hogs, and grew vegetables.

During the time Manzanar was open, 188 weddings took place. 541 children were born in the camp. Between 135 and 146 people died there.

Weather and Environment

The Manzanar camp was located between Lone Pine and Independence. The weather was very hard on the people held there. Most were from the Los Angeles area and were not used to such extreme temperatures. The temporary buildings did not protect them well from the weather.

The Owens Valley is about 4,000 feet (1,200 meters) high. Summers were very hot, often over 100°F (38°C). Winters brought snow and cold temperatures. High winds were common day and night.

The area gets very little rain, only about five inches (12.7 cm) a year. The constant dust was a big problem because of the strong winds. People often woke up covered in dust and had to constantly sweep dirt from their barracks.

Former prisoner Ralph Lazo said, "In the summer, the heat was unbearable. In the winter, the sparsely rationed oil didn't adequately heat the tar paper-covered pine barracks with knotholes in the floor. The wind would blow so hard, it would toss rocks around."

Camp Layout and Buildings

The camp was built on 6,200 acres (2,500 ha) of land. The main part of the camp covered about 540 acres (220 ha). There were eight guard towers with machine guns around the camp's fence. The fence was topped with barbed wire. The camp had a standard grid layout, similar to other relocation centers.

The living area was about one square mile (2.6 km²). It had 36 blocks of quickly built barracks. These barracks were 20 feet (6.1 m) by 100 feet (30.5 m) long. Each family, up to eight people, lived in a single "apartment" that was 20 feet (6.1 m) by 25 feet (7.6 m).

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, who was held at Manzanar, described the living conditions. She wrote that the shacks were made of pine boards covered with tar paper. There were gaps between the boards, which grew wider as the wood dried. Knotholes in the floor also let in dirt. Each apartment had one light bulb, an oil stove for heat, and army blankets and cots.

The apartments had partitions but no ceilings, so there was no privacy. This lack of privacy was a big issue, especially with shared bathrooms and showers. Former prisoner Rosie Kakuuchi said the shared facilities were "one of the hardest things to endure." Neither the bathrooms nor showers had partitions.

Each living block also had a shared dining hall, a laundry room, a recreation hall, and an ironing room. There were also staff houses, offices, warehouses, a hospital, and firebreaks.

The camp had schools, a high school auditorium, a cemetery, a post office, and an orphanage. Some facilities were built later. Armed military police guarded the camp from watchtowers. They also had sentry posts at the main entrance.

Food and Meals

The barracks at Manzanar had no cooking areas. All meals were served in large dining halls. Lines for meals were long and often stretched outside, no matter the weather. This cafeteria-style eating changed family life. Children often wanted to eat with friends instead of their families.

There was a strict meal schedule. One young prisoner noted, "We eat from 7:00 AM to 8:00 AM o'clock in the morning 12:00 PM-1:00 PM in afternoon and 5:00 PM-6:00 in night and on Sunday we eat 8:00 AM-9:00." Food at Manzanar followed military requirements. Meals usually had hot rice and vegetables. Meat was rare due to rationing.

In 1944, a chicken ranch and a hog farm started. These provided some meat for the camp. Many prisoners were farmers. They used their skills to grow successful gardens. They even made their own soy sauce and tofu. Many families had small gardens outside their barracks.

The food quality varied but was often not as good as what people ate before being imprisoned. Togo Tanaka said people "got sick from eating ill-prepared food." Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga described her baby not gaining enough weight because of the poor food.

The food was often starchy and low quality. It included things like Vienna sausages, canned string beans, hot dogs, and apple sauce. Meat was rare, usually chicken or mutton. Frank Kikuchi, a prisoner, said newspapers sometimes lied to the public. They claimed prisoners were getting "steaks, chops, eggs, or eating high off the hog."

Camp, school, and individual gardens helped improve the food. Prisoners also sometimes snuck out to fish. They would bring their catches back to the camp.

Work and Jobs

Most adults at Manzanar had jobs to help run the camp. The camps were meant to be self-sufficient. People worked in many different areas. These included making clothes and furniture, farming, and tending orchards. They also worked in military manufacturing, like making camouflage nets.

Some worked as teachers, police, firefighters, or nurses. Others had general service jobs in stores, beauty parlors, and a bank.

A farm and orchards provided vegetables and fruits for the camp. People of all ages helped maintain them. By summer 1943, farms produced many vegetables. Eventually, over 400 acres (160 ha) of farms produced more than 80 percent of the camp's food. In 1944, a chicken ranch and a hog farm opened. These provided much-needed meat.

Unskilled workers earned $8 per month. Semi-skilled workers earned $12 per month. Skilled workers made $16 per month. Professionals earned $19 per month. Everyone also received $3.60 per month for clothes.

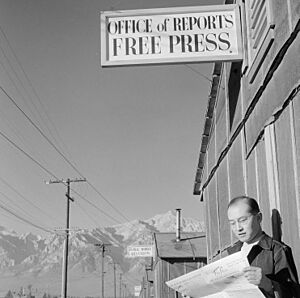

The Manzanar Free Press Newspaper

The Manzanar Free Press was the camp newspaper. It was first published on April 11, 1942. It continued until October 19, 1945. The paper had both Japanese and English sections.

At first, it was four pages and printed by hand. As more people arrived, it was published three times a week. A printing press was brought in, and the paper grew to six pages.

Journalists like Togo Tanaka worked for the newspaper. Tanaka wrote many articles about daily life in the camp. Chiye Mori, a poet and journalist, also became an editor.

Even though it was called "Free Press," the War Relocation Authority (WRA) controlled its content. The paper published announcements from the camp, news from other camps, and WRA rules. Some content was not allowed to be published. The paper also covered life in the camps, sports, and war news.

Fun and Recreation

People found ways to make life at Manzanar better through recreation. They played many sports, including baseball, football, basketball, soccer, volleyball, and softball. A nine-hole golf course was even built.

Lou Frizzell was the music director. Under his guidance, Mary Nomura became known as the "songbird of Manzanar." She sang at dances and other events. There were also theater performances. These included original plays by prisoners and traditional Japanese kabuki and noh plays.

Many prisoners were landscapers from Los Angeles. They made the barren camp beautiful by building amazing gardens and parks. These often had pools, waterfalls, and rock designs. There were even competitions between landscapers. These gardens helped create a sense of community and offered a place for healing. Some parts of these gardens can still be seen at Manzanar today.

One of the most popular activities was baseball. Men formed almost 100 baseball teams, and women formed 14. They had regular seasons and championship games. Some players felt playing baseball showed their loyalty to America. Photographer Ansel Adams took a famous photo of a baseball game. He wanted to show how prisoners "overcome [their] sense of defeat and despair."

Japanese cultural celebrations continued in the camp. The New Year tradition of mochitsuki (pounding rice into mochi) was often covered by the camp newspaper. Craftsmen made geta (wooden sandals) for many residents.

The Manzanar Disturbance

While most people quietly accepted their situation, there was some resistance in the camps. Other camps also had problems over pay, food shortages, and rumors. The most serious event happened at Manzanar on December 5–6, 1942. It became known as the "Manzanar Revolt" or "Manzanar Riot."

Some tension came from differences in jobs and pay. Nisei (Japanese Americans born in the U.S.) and members of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) sometimes got better treatment. Rumors spread that camp leaders were stealing food and selling it. On December 5, JACL leader Fred Tayama was beaten. Harry Ueno, a leader of the Kitchen Workers Union, was arrested as a suspect.

About 200 prisoners met on December 6 to discuss what to do. Later, between two and four thousand people gathered. They listened to speeches and chose five people to talk to the camp director. The crowd followed these representatives. The camp director called in military police to control the crowd.

The representatives demanded Ueno's release. The director eventually agreed, but only if Ueno would still face trial. The crowd was asked to leave and not gather again. Ueno was returned to the camp jail.

When the representatives went to check on Ueno, the crowd returned. Instead of leaving, they split into groups to find Tayama and other suspected collaborators. They couldn't find them. The searchers then started heading back to the jail.

The crowd became angrier and began throwing bottles and rocks at the soldiers. The military police used tear gas to scatter them. As people ran, some pushed a truck toward the jail. At that moment, the military police fired into the crowd. A 17-year-old boy was killed instantly. A 21-year-old man died a few days later. At least nine others were wounded.

That night, some prisoners continued to attack suspected collaborators. Over the next few days, those marked as collaborators were quietly moved out of the camp with their families for their safety.

Japanese American Soldiers

Japanese American soldiers formed important combat units during World War II. The 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate) was formed in June 1942. Their training showed the War Department that Japanese American soldiers could be trusted in combat. This led to the creation of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) on February 1, 1943.

The 100th Battalion fought bravely in Italy starting in September 1943. Their courage paved the way for the 442nd RCT to join them in June 1944.

President Roosevelt allowed the 442nd RCT to form after many groups pushed for Japanese Americans to serve. In Hawaii, 10,000 young men signed up. About two-thirds of the 442nd RCT were from Hawaii, and one-third were from the mainland.

In Hawaii, fewer than 2,000 people of Japanese descent were imprisoned. This is much less than on the West Coast. So, less than 2% of the soldiers from Hawaii had families in the camps.

The Camp Closes

The WRA closed Manzanar on November 21, 1945. It was the sixth camp to close. The U.S. government had brought Japanese Americans to the Owens Valley. But they had to leave the camp and travel on their own.

The WRA gave each person $25 (about $420 today). They also received a one-way train or bus ticket and meals if they had less than $600 (about $10,000 today).

Many people left willingly. But a large number refused to leave. They had lost everything and had nowhere to go. So, they were forced to leave Manzanar again, sometimes by force.

Between 135 and 146 Japanese Americans died at Manzanar. Fifteen were buried there. Only five graves remain, as most were reburied by their families elsewhere. The Manzanar cemetery has a monument built by stonemason Ryozo Kado in 1943. The Japanese inscription on the front means "Soul Consoling Tower."

After the camp closed, the site returned to its original state. Within a few years, almost all buildings were removed. Only two sentry posts at the entrance, the cemetery monument, and the former Manzanar High School auditorium remained. The auditorium was bought by Inyo County.

The site still has many building foundations, parts of the water and sewer systems, and the old road layout. It also shows signs of the ranches and the town of Manzanar. And it has artifacts from the time of the Owens Valley Paiute settlement.

Remembering Manzanar

During the war, the War Relocation Authority hired photographers Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange. They took pictures to document the Japanese Americans affected by the forced relocation. Togo Tanaka and Joe Masaoka were hired as historians for the camp.

The Manzanar Pilgrimage

On December 21, 1969, about 150 people traveled from Los Angeles to Manzanar. This was the first official annual Manzanar Pilgrimage. However, two ministers had been making yearly trips to Manzanar since the camp closed in 1945.

The non-profit Manzanar Committee has sponsored the Pilgrimage since 1969. It happens every year on the last Saturday of April. Hundreds of visitors, including former prisoners, gather at the Manzanar cemetery. They remember the imprisonment. The goal is to learn from this sad part of American history and make sure it never happens again. The event includes speakers, cultural performances, and a service for those who died at Manzanar.

In 1997, the Manzanar At Dusk program started. It brings together local residents and descendants of Manzanar's past. In small groups, people can hear stories directly from those who were there. They talk about how Manzanar's history relates to their own lives.

Since the September 11 attacks, American Muslims have joined the Pilgrimage. They want to raise awareness about civil rights. They compare the treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II to how Muslims are sometimes treated today. In 2019, over 2,000 people visited for the 50th anniversary. Many Muslim speakers attended, and a group of Muslims held afternoon prayers at the monument.

Manzanar Becomes a Historic Site

The Manzanar Committee worked hard to get Manzanar recognized. In 1972, the State of California named Manzanar a California Historical Landmark. A historical marker was placed there in 1973. Manzanar was also named a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 1976.

The committee also pushed for Manzanar to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In February 1985, Manzanar became a National Historic Landmark. Then, in March 1992, President George H. W. Bush signed a law. This law made Manzanar a National Historic Site. It was created "to provide for the protection and interpretation of the historical, cultural, and natural resources associated with the relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II." Five years later, the National Park Service bought 814 acres (329 ha) of land at Manzanar. It was the first camp to become a National Historic Site.

Challenges to Preserving Manzanar

After Manzanar became a National Historic Site in 1992, some people protested. They sent letters saying Manzanar should be called a "guest housing center." Others said calling it a "concentration camp" was "treason." Some even threatened to destroy buildings. The California State historical marker was damaged. A man even said he drove 200 miles to urinate on the marker.

Visiting Manzanar Today

The Manzanar National Historic Site has a visitor center and a gift shop. These are in the restored Manzanar High School Auditorium. The auditorium and the two sentry posts at the entrance are the only original buildings from the camp's time. Exhibits tell stories of the prisoners, the Owens Valley Paiute, the ranchers, and the town of Manzanar. They also explain how water shaped the valley's history. A video of Ronald Reagan signing the Civil Liberties Act is also shown.

An "interpretive center" helps visitors understand the prisoners' experiences. The exhibits use materials similar to those used when the camp was open. Details about camp life come from all ten relocation centers. Visitors can also take a driving tour with 27 points of interest.

A dining hall, moved from a military facility, was added in 2002. A replica guard tower was built in 2005. The Manzanar cemetery has the memorial monument built by masons in 1943. All the remains of those buried there have been moved to other places.

The site has restored sentry posts and a replica guard tower. There is a self-guided tour road and outdoor exhibits. Staff offer guided tours and educational programs. There's even a Junior Ranger program for children aged four to fifteen.

Rebuilding Parts of the Camp

The National Park Service usually avoids rebuilding old structures. But they make exceptions when it helps explain history and there's enough information to rebuild accurately. After talking with the Japanese-American community, the NPS decided to rebuild some parts of Manzanar. They also preserve the parts that still exist.

The National Park Service is rebuilding one of the 36 living blocks (Block 14). One barrack shows how it looked when Japanese Americans first arrived in 1942. Another barrack shows how life was in 1945. These exhibits opened in 2015. A restored World War II dining hall, moved to the site in 2002, opened to visitors in 2010. The Manzanar National Historic Site also launched a virtual museum in 2010.

National Park Service staff continue to find artifacts from Manzanar's history. They have also dug up several gardens built there, including Merritt Park. A classroom exhibit is being planned for the Block 9 barracks. A replica of the Block 9 women's latrine opened in 2016.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Manzanar para niños

In Spanish: Manzanar para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |