War Relocation Authority facts for kids

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency. It was created to manage the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. This meant that many people of Japanese descent living in the U.S. were forced to move to special camps. The WRA also managed the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York. This was the only refugee camp in the U.S. for people escaping Europe during the war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the WRA on March 18, 1942. It was closed by President Harry S. Truman on June 26, 1946.

Contents

Why the WRA Was Formed

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. government became worried about national security. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order allowed military leaders to create special zones. People who might be a threat to national security could be removed from these zones.

Soon after, large areas of California, Washington, Oregon, and Arizona were declared "military areas." Japanese Americans living in these areas were told they would have to leave their homes. This order also applied to Alaska. This meant the entire U.S. West Coast was off-limits for Japanese nationals and Americans of Japanese descent.

On March 18, 1942, the WRA was officially formed by Executive Order 9102. Milton S. Eisenhower was its first director. He did not agree with the idea of putting so many people in camps. He tried to let women and children stay free, but he was not successful. Eisenhower wanted the camps to be like small farming communities. He also tried to help Japanese Americans move to other parts of the country where workers were needed. However, governors in those states were concerned and said it was "politically impossible."

Eisenhower was the WRA director for only 90 days. He resigned on June 18, 1942. During his time, he worked to improve conditions. He raised wages for people in the camps. He also helped create a student program for college-age Nisei (Japanese Americans born in the U.S.). He asked Congress to create programs to help people after the war. Eisenhower was replaced by Dillon S. Myer. Myer led the WRA until it closed.

Before the WRA built its permanent camps, Japanese Americans were first moved to temporary "assembly centers." These were run by a different military group. Myer's main job was to continue building the more permanent WRA camps.

Choosing Camp Locations

The WRA looked at 300 possible places for the camps. They finally chose ten locations. Most of these were on tribal lands. The WRA had several rules for choosing a camp site:

- It had to offer jobs in public works, farming, or manufacturing.

- It needed good transportation, power, soil, water, and climate.

- It had to be big enough for at least 5,000 people.

- It had to be on public land.

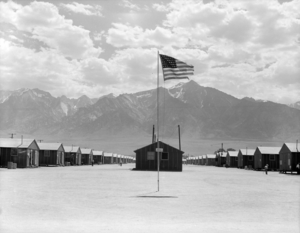

The camps had to be built from scratch. There were shortages of workers and wood during the war. Also, some WRA camps became very large, like small cities. This meant many camps were not finished when people started arriving. For example, at Manzanar, people living in the camp helped finish building it.

Life Inside the Camps

Life in a WRA camp was challenging. People who found jobs worked long hours, often in farming. Most Japanese Americans in the camps focused on daily life. They tried to make their living spaces better. They also sought education and prepared for when they could leave. Many found their jobs important, especially if they were responsible roles. However, the pay was much lower than outside the camps. This was done to stop rumors that Japanese Americans were getting special treatment. Unskilled workers earned $14 a month. Doctors and dentists made only $19 a month.

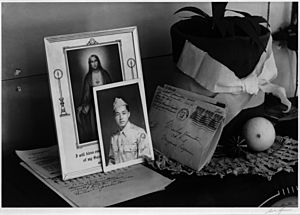

Many people found comfort in religion. Both Christian and Buddhist services were held regularly. Others focused on hobbies or took classes. These classes included American history, job skills like bookkeeping, and cultural arts like ikebana (Japanese flower arrangement). Young people spent time on sports, plays, and dances. News about these activities filled the camp newspapers.

Living space was very small. Families lived in army-style barracks. These barracks were divided into "apartments." The walls usually did not reach the ceiling. The largest "apartments" were about 20 by 24 feet. They were expected to house a family of six. In April 1943, each person at the Topaz camp had about 114 square feet of space.

Everyone ate in common dining halls, assigned by their living block. The WRA spent about 50 cents per person per day on food. This was also to counter rumors of "coddling" the people in the camps. However, many people grew their own food in the camps to add to their meals.

The WRA allowed Japanese Americans to have some self-governance. Elected leaders worked with WRA supervisors to help run the camps. This kept people busy and gave them some say in daily life. It also helped the WRA's goal of "Americanizing" people. This was so they could fit into white communities after the war. However, the WRA still made the most important decisions.

Leaving the Camps

Director Dillon Myer wanted people to leave the camps and rejoin outside communities. He worried that people would become too dependent on the government. Even before the permanent camps were built, some farm workers were allowed to leave for temporary jobs. Also, the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council helped college students attend schools outside the camps.

The WRA started its own "leave permit" system in July 1942. At first, it was hard to apply. But the process became simpler over time. By the end of 1942, only 884 people had left the camps.

In 1943, the application process changed again. People now only needed to fill out a registration form and pass a background check. This form became known as the "loyalty questionnaire." It was later made mandatory for all adults. The questionnaire asked about loyalty to the U.S. and willingness to serve in the military. Many people felt insulted by these questions. They felt it questioned their loyalty to the United States. Most answered yes to the questions. However, about 15 percent refused to answer or answered "no."

The WRA then began to focus on helping people resettle. Offices were set up in cities like Chicago and Salt Lake City. These offices helped people find housing, jobs, and education. WRA officials encouraged people to move to cities without large Japanese American populations. They also advised against speaking Japanese or holding onto too many cultural ties. By the end of 1944, nearly 35,000 people had left the camps. Most of them were Nisei.

Challenges and Protests

The WRA wanted Japanese Americans to adopt American customs. They sponsored patriotic activities and English classes. They also encouraged young men to join the U.S. Army. People who followed the WRA's rules were rewarded. Those who protested their confinement were seen as a security threat.

There were tensions over poor working conditions, low wages, and bad housing. There were also rumors of guards stealing food. These issues led to protests. Workers went on strike at Poston, Tule Lake, and Jerome camps. In November and December 1942, there were violent incidents at Poston and Manzanar. People suspected of working with the WRA were attacked. These events led to government investigations.

The "loyalty questionnaire" caused a lot of anger. It asked 28 questions, including if people would serve in combat and give up loyalty to the Emperor of Japan. Many were upset about being asked to risk their lives for a country that had imprisoned them. They also felt the allegiance question implied they were disloyal.

About 15 percent of people refused to answer or answered "no" to key questions. These people were called "no-nos." In July 1943, Tule Lake was made into a special high-security camp for these "no-nos." About 12,000 people were moved to Tule Lake. This caused overcrowding and more problems.

Conditions worsened after a labor strike and a large protest. The camp was placed under military control in November 1943. During this time, many men were imprisoned. The general population faced curfews and searches. Some angry young men joined groups like the Hoshi-dan. These groups were pro-Japan and aimed to prepare members for life in Japan. In July 1944, the Renunciation Act was passed. This allowed people to give up their U.S. citizenship. About 5,589 people, mostly from Tule Lake, gave up their citizenship. They applied to move to Japan.

The Camps Close

The West Coast was reopened to Japanese Americans on January 2, 1945. Director Dillon Myer wanted it opened sooner. But it was delayed until after the November 1944 election. On July 13, 1945, Myer announced that most camps would close between October 15 and December 15 of that year. Tule Lake was the last to close. It held people who had given up their U.S. citizenship and were waiting to go to Japan. Many of these people later regretted their decision and fought to stay in the U.S.

Despite protests from people who had nowhere to go, the WRA began to cut services. Those who remained were eventually forced to leave the camps and return to the West Coast.

Tule Lake closed on March 20, 1946. President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9742 on June 26, 1946. This order officially ended the WRA's mission.

Relocation Centers

- Gila River War Relocation Center

- Granada War Relocation Center

- Heart Mountain War Relocation Center

- Jerome War Relocation Center

- Manzanar War Relocation Center

- Minidoka War Relocation Center

- Poston War Relocation Center

- Topaz War Relocation Center

- Tule Lake War Relocation Center

- Rohwer War Relocation Center

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |