Heart Mountain Relocation Center facts for kids

|

Heart Mountain Relocation Center

|

|

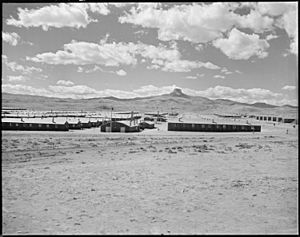

Heart Mountain historical marker and mountain behind.

|

|

| Location | Park County, Wyoming, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Ralston, Wyoming |

| Built | 1942 |

| Architect | US Army Corps of Engineers; Hazra Engineering; Hamilton Br. Co. |

| NRHP reference No. | 85003167 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | December 19, 1985 |

| Designated NHL | September 20, 2006 |

The Heart Mountain War Relocation Center was a special camp in Wyoming, located between the towns of Cody and Powell. It was one of ten such camps built during World War II. These camps were used to hold Japanese Americans who were forced to leave their homes on the West Coast.

This happened after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. President Franklin Roosevelt ordered that people of Japanese descent be moved away from the coast. This was a very difficult time for many families.

Construction of the camp began in June 1942. It had 650 military-style buildings and guard towers. The first Japanese Americans arrived on August 11, 1942. They came by train from temporary "assembly centers" in places like Pomona and Portland.

Over three years, Heart Mountain held nearly 14,000 Japanese Americans. At its busiest, it was the third-largest "town" in Wyoming. The camp closed on November 10, 1945.

Heart Mountain is well-known because many young residents bravely challenged the government. They protested being drafted into the U.S. military while their families were still held in the camp. The Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee encouraged people to refuse the draft until their rights were given back. Heart Mountain had the highest number of draft resisters among all the camps.

In 1988 and 1992, the U.S. government formally apologized for these actions. They also set up a fund to pay a small amount of money to those who had been held in the camps.

Today, the Heart Mountain site is one of the best-preserved camps. You can still see the old street layout and many building foundations. Some original buildings remain, and others have been moved back. In 2007, part of the center became a National Historic Landmark.

The Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation runs the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. It opened in 2011 in Powell. This museum shares the stories of Japanese Americans during the war. It shows how unfair prejudice led to their forced relocation.

Contents

Why Heart Mountain Was Built

Before the War

The land where Heart Mountain was built was originally part of a big irrigation project. This project aimed to bring water to dry land in Wyoming. In 1897, William "Buffalo Bill" Cody bought a large area of land. He planned to irrigate it for farming.

Later, the federal government took over the project. In 1937, during the Great Depression, workers began building canals. This was part of a government effort to create jobs and improve the country's infrastructure. However, construction stopped when the United States entered World War II.

A Difficult Order

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, fear and prejudice against Japanese Americans grew. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. This order allowed military leaders to create "exclusion zones." From these zones, certain people could be removed.

Soon, the entire West Coast of the United States was declared an exclusion zone. Japanese Americans, along with some Italian and German Americans, were ordered to leave these areas. Over 110,000 Japanese Americans were forced from their homes. They were first sent to temporary "assembly centers." These were often large public spaces like fairgrounds. Meanwhile, permanent "relocation centers" like Heart Mountain were being built.

Building the Camp

On May 23, 1942, the government announced a new camp would be in Wyoming. Heart Mountain was chosen because it was far away from cities but still had access to water and a railroad. This made it easy to bring in people and supplies.

On June 1, 1942, the land was given to the War Relocation Authority. This group was in charge of the incarceration program. More than 2,000 workers began building the camp on June 8. They put up a tall barbed wire fence and nine guard towers around 740 acres of land.

Inside, 650 military-style barracks were built in a grid pattern. These included living areas, a hospital, schools, and other facilities. The buildings had electricity, which was unusual for Wyoming at the time. However, they were built very quickly and often poorly. Workers were told they could get a job "if you can drive a nail." The camp was also designed to grow much of its own food.

Life Inside the Camp

Daily Life

The first people arrived at Heart Mountain on August 12, 1942. They came from places like Los Angeles and San Francisco. Families were given a barracks unit based on their size. They tried to make their new "apartments" more comfortable. They hung bed sheets for privacy and stuffed rags into cracks to keep out dust and cold. Some even ordered tools to make repairs.

Each barracks unit had one light, a wood-burning stove, and a cot and two blankets for each person. Bathrooms and laundry rooms were shared in separate buildings. Meals were served in large dining halls. Armed military police watched over the camp from the guard towers.

European-American administrators ran the camp. However, some Japanese Americans, called Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans born in the U.S.), became block managers. Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) served on councils. They helped with some camp administration. People could work in the hospital, schools, or camp factories. But the pay was very low, only $12–$19 a month. This was much less than what non-Japanese American workers earned for similar jobs.

School and Fun

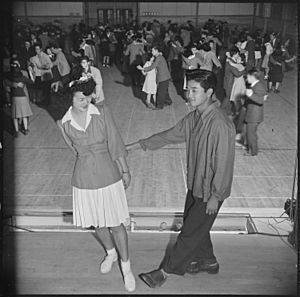

Children in the camp started school in barracks classrooms in October 1942. Books and furniture were scarce. Still, going to school helped children feel a sense of normal life. By May 1943, a high school was built. It had regular classrooms, a gym, and a library. The high school's football team, the Heart Mountain Eagles, even played against local high school teams.

Other activities helped people pass the time. There were sporting events, movie theaters, religious services, and craft groups. Knitting, sewing, and woodcarving were popular. They also helped people improve their living conditions. Boy and Girl Scout programs were very popular among children. Heart Mountain had more scout troops than any other camp. Scouts went hiking, made crafts, and swam.

Standing Up for Rights

Refusing the Draft

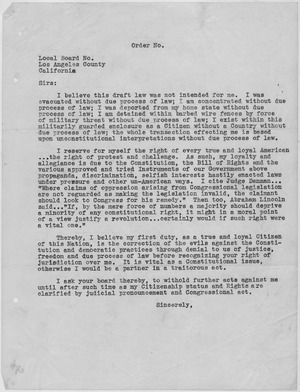

In early 1943, camp officials gave out a "loyalty questionnaire." It had two questions that caused a lot of trouble. Question 27 asked if men would serve in the armed forces. Question 28 asked people to give up loyalty to the Emperor of Japan. Many people were confused or felt insulted by these questions. They worried that any answer could be used against them. Some answered "no" or gave a conditional answer, like "I will serve when I am free."

Soon after, Kiyoshi Okamoto started the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee. This group protested the unfair treatment of Japanese American citizens. Frank Emi and others put up flyers encouraging people not to answer the questions.

When draft orders came to Heart Mountain, the Fair Play Committee held meetings. They talked about how it was wrong to force people to serve while they were held as prisoners. They encouraged others to refuse military service until their freedom was restored. On March 25, 1944, twelve Heart Mountain resisters were arrested for not reporting for their physicals.

In July 1944, 63 Heart Mountain residents were put on trial. They were found guilty of refusing to join the army. In total, 300 draft resisters from eight camps were arrested. Most served time in federal prison. The seven leaders of the Fair Play Committee were also sent to prison. Heart Mountain had the highest rate of draft resistance among all the camps.

Heroes from Heart Mountain

Even with the resistance, about 650 young men from Heart Mountain joined the U.S. Army. They either volunteered or were drafted into famous units like the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Fifteen of these young men died in battle, and 52 were wounded.

Joe Hayashi and James K. Okubo were two heroes from Heart Mountain. They both received the Medal of Honor for their bravery. This is the highest military award. Heart Mountain is the only camp to have more than one Medal of Honor recipient. In late 1944, camp residents built an Honor Roll. It listed the names of these soldiers. A new, accurate copy of this tribute stands there today.

The Camp Closes

By December 1944, President Roosevelt ended Executive Order 9066. Japanese Americans could start returning to the West Coast the next month. Many had already left to work or go to college in other parts of the country.

Starting in January 1945, people began leaving Heart Mountain. Administrators gave them $25 and a train ticket back to where they came from. However, many Japanese Americans had nothing to return to. Unfair laws in California had prevented them from owning their homes and farms. Also, Wyoming had laws that stopped Japanese Americans from buying land or even voting. This made it hard for them to stay in Wyoming. The last group of former residents left Heart Mountain on November 10, 1945.

Remembering Heart Mountain

After Heart Mountain closed, most of the land and buildings were sold. Farmers and former soldiers bought them to create new homes and farms. Today, only parts of the hospital, a high school shed, a root cellar, the Honor Roll, and one remodeled barracks building remain.

The Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation started in 1996. This group works to preserve the site and its history. They want to teach people about the Japanese American incarceration. They also support research so future generations can learn from this experience.

The Foundation helped the site become a National Historic Landmark in 2007. On August 20, 2011, they opened the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. This museum has exhibits, photos, and stories about the wartime incarceration. It also explores issues of race and fairness in America. Visitors can walk around the site and see the remaining structures.

Famous people like former U.S. Secretary of Transportation Norman Mineta and retired U.S. Senator Alan K. Simpson were advisors to the Foundation. They met as Boy Scouts at Heart Mountain, on opposite sides of the fence. The Foundation also hosts an annual gathering at Heart Mountain.

What Do We Call It?

There has been a lot of discussion about what to call Heart Mountain and the other camps. People have used terms like "War Relocation Center," "relocation camp," "internment camp," and "concentration camp."

Many scholars and activists believe "internment camp" is not strong enough. They say it sounds too mild. Japanese Americans were not there for their protection. They were forced to work and could not leave. The debate about the most accurate term continues today.

Notable People from Heart Mountain

Many people who lived at Heart Mountain went on to do important things. Here are a few:

- Kathryn Doi (born 1942), a judge in California.

- Frank S. Emi (1916–2010), a leader of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee and a civil rights activist.

- Sadamitsu "S. Neil" Fujita (1921–2010), a graphic designer who served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

- Joe Hayashi (1920–1945), a soldier who bravely served and received the Medal of Honor.

- Bill Hosokawa (1915–2007), an author and journalist who edited the camp newspaper.

- Kiyoshi Kuromiya (1943–2000), an author and advocate for civil rights.

- Yosh Kuromiya (1923–2018), a member of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee who resisted the draft.

- Norman Mineta (1931–2022), who became a U.S. Secretary of Transportation and Secretary of Commerce.

- James K. Okubo (1920–1967), another brave soldier who received the Medal of Honor.

- Albert Saijo (1926–2011), a poet.

Other Camps Like Heart Mountain

Heart Mountain was one of ten such camps. Here are some of the others:

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |