Topaz War Relocation Center facts for kids

|

Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz)

|

|

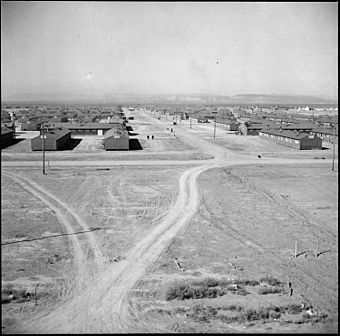

Looking down a main thoroughfare at Topaz (October 18, 1942)

|

|

| Location | Millard County, Utah, United States |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Delta, Utah |

| Area | 300 acres (120 ha) |

| Built | 1942 |

| Architect | Daley Brothers |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001934 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | January 2, 1974 |

| Designated NHL | March 29, 2007 |

The Topaz War Relocation Center was a special camp in Utah where people of Japanese descent were held during World War II. These people, called Nikkei (which includes both American citizens and immigrants from Japan), were forced to leave their homes.

In February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order made it possible to move people of Japanese ancestry into these "relocation centers" like Topaz. Most people sent to Topaz came from the San Francisco Bay Area and were first held at the Tanforan Assembly Center. The Topaz camp opened in September 1942 and closed in October 1945.

The camp was about 15 miles (24 km) west of Delta, Utah. It covered a large area, with a main living space of 640 acres (259 ha). About 9,000 people lived and worked at Topaz, making it the fifth-largest city in Utah at that time. The weather in the desert area was very extreme, with big temperature changes. The living barracks were not well insulated, making conditions uncomfortable, even after stoves were added.

Topaz had two elementary schools, a high school, a library, and places for fun activities. Life in the camp was recorded in a newspaper called Topaz Times and a literary magazine called Trek. People worked inside and outside the camp, often in farming. Many talented artists lived at Topaz.

In 1983, Jane Beckwith started the Topaz Museum Board. Topaz was named a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 2007. After many years of hard work, the Topaz Museum was built in Delta. It shows art made at Topaz and tells the stories of the people who lived there.

Contents

What Was Topaz Called?

Since World War II ended, people have discussed what to call places like Topaz. The U.S. government used terms like "relocation camp" or "relocation center." However, many people, including the Topaz Museum Board, believe "detention camp" or "concentration camp" and "prisoners" or "internees" are more accurate terms. This is because people were held there against their will.

Why Was Topaz Built?

In December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Soon after, in February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order forced about 120,000 people of Japanese descent to leave their homes on the West Coast of the United States. Most of these people were American citizens (called Nisei) or Japanese-born residents (called Issei).

About 5,000 people left the restricted areas on their own to avoid being sent to camps. But the remaining 110,000 were moved from their homes by the Army.

Topaz opened on September 11, 1942. It became Utah's fifth-largest city, with over 9,000 people living there at its peak. In total, 11,212 people lived at Topaz at some point. Utah's governor, Herbert B. Maw, did not want Japanese Americans moved into the state. He argued that if they were a danger to the West Coast, they would be a danger to Utah too.

Most people arrived at Topaz from temporary centers like Tanforan or Santa Anita. Many came from the San Francisco Bay Area. About 65% of the people were Nisei, meaning they were American citizens born to Japanese immigrant parents. The camp closed on October 31, 1945.

Topaz was first called the Central Utah Relocation Authority. Then it was called the Abraham Relocation Authority. But these names were too long for the post office. The final name, Topaz, came from Topaz Mountain, which is about 9 miles (14 km) away. Topaz was the main camp in Utah.

Life at Topaz Camp

Weather and Environment

Most people at Topaz came from the San Francisco Bay Area, which has mild, wet winters and dry summers. Topaz, however, had a very extreme climate. It was located in the Sevier Desert, 4,580 feet (1,396 m) above sea level. Temperatures could change a lot during the day. The area also had strong winds and dust storms. One storm in 1944 damaged 75 buildings.

Temperatures could drop below freezing from mid-September to late May. The average temperature in January was 26°F (-3°C). Spring rains turned the clay soil into mud, which brought mosquitoes. Summers were hot, sometimes over 100°F (38°C), with occasional thunderstorms. The first snow in 1942 fell on October 13, before the camp was even finished.

Buildings and Living Spaces

Topaz had a living area called the "city," which was about 1 square mile (2.6 km²). It also had large areas for farming. Inside the city, 42 blocks were for the people living there. Each residential block held 200–300 people. They lived in barracks, with five people sharing a 20 by 20 foot (6.1 by 6.1 m) room. Families usually stayed together. Single adults shared rooms with four other people.

Each residential block also had a recreation hall, a dining hall, an office for the block manager, and a building for laundry, toilets, and bathing. There were only four bathtubs for all the women and four showers for all the men in each block. These crowded conditions meant people had little privacy.

The barracks were made of wood frames covered in tarpaper, with wooden floors. Many people moved in before the barracks were finished, which meant they faced harsh weather. Later, the walls were lined with sheetrock and the floors filled with masonite. Construction started in July 1942, but people moved in by September 1942. The camp was not fully completed until early 1943. Some 214 people volunteered to arrive early and help build the camp.

Rooms were heated by pot-bellied stoves. No furniture was provided. People used leftover wood from construction to build beds, tables, and cabinets. Some families used fabric to divide their living spaces. Water came from wells and was stored in a large wooden tank. The water was "almost undrinkable" because it was very alkaline.

Topaz also had shared areas like a high school, two elementary schools, a 28-bed hospital, at least two churches, and a community garden. There was a cemetery, but it was never used. All 144 people who died in the camp were cremated. Their ashes were held until after the war for burial. The camp was guarded by 85–150 policemen. It was surrounded by a barbed wire fence with watchtowers every 0.25 miles (400 m) that had searchlights.

Daily Life and Activities

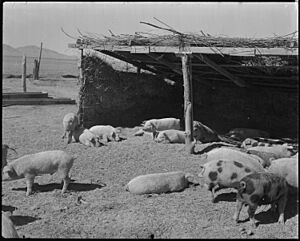

The camp was designed to be self-sufficient. Most of the land was used for farming. People at Topaz raised cattle, pigs, and chickens. They also grew crops and vegetables. The vegetables were very good and won awards at the Millard County Fair. However, due to bad weather, poor soil, and short growing seasons, the camp could not grow all the food needed for the animals.

Topaz had two elementary schools: Desert View Elementary and Mountain View Elementary. Topaz High School taught students from grades 7–12. There was also a program for adult education. Both local teachers and people living in the camp taught at the schools. The schools were often crowded and lacked supplies, but the teachers were very dedicated. Topaz High School created a strong community, and former students had many reunions after the war.

Sports were popular in the schools and among adults. People played baseball, basketball, and even practiced sumo wrestling. Many cultural groups formed in the camp. Topaz had its own newspaper, the Topaz Times, and a literary magazine, Trek. There were also two libraries with almost 7,000 books in both English and Japanese. Artist Chiura Obata led an art school at Topaz, teaching art to over 600 students.

Sometimes, people were allowed to leave the camp for work. In 1942, some got permission to work in nearby Delta. They helped with farming because many local workers had joined the military. In 1943, over 500 people from Topaz worked in seasonal farming jobs outside the camp. Another 130 worked in other jobs.

People were also sometimes allowed to leave the camp for fun. A former camp at Antelope Springs, about 90 miles (145 km) west, was used as a recreation area for people living in Topaz and camp staff. Two buildings from Antelope Springs were moved to the main camp to be used as Buddhist and Christian churches. During a rock hunting trip, two men, Akio Uhihera and Yoshio Nishimoto, found a very rare 1,164 lb (528 kg) iron meteorite. The Smithsonian Institution later bought it.

After Topaz Closed

After Topaz closed, the land was sold. Most of the buildings were sold off, taken apart, and moved. Even the water pipes and utility poles were sold. Today, you can still see many foundations and other ground-level features at the site. But few buildings remain, and nature has taken over most of the abandoned areas.

In 1976, the Japanese American Citizens League placed a monument at the camp site. On March 29, 2007, the "Central Utah Relocation Center Site" was named a National Historic Landmark.

In 1982, Jane Beckwith, a teacher at Delta High School, and her journalism students began studying Topaz. She helped create the Topaz Museum Board in 1983. The Topaz Museum first shared space with another museum. With funding, the Topaz Board built its own museum building in 2013. In 2015, the museum officially opened with an exhibit of art created at Topaz. The museum closed for updates in November 2016 and reopened in 2017 as a traditional museum focusing on the history of Topaz. By 2017, the Topaz Museum and Board had bought 634 of the original 640 acres of the camp site.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |