Tule Lake War Relocation Center facts for kids

|

Tule Lake War Relocation Center

|

|

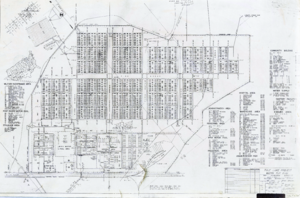

View of the Tule Lake War Relocation Center

photographed by Russell Lee, 1942 |

|

| Location | Northeast side CA 139, Newell, California |

|---|---|

| Website | Tule Lake National Monument |

| NRHP reference No. | 06000210 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | February 17, 2006 |

| Designated NHL | February 17, 2006 |

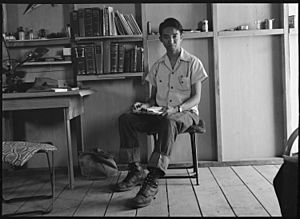

The Tule Lake War Relocation Center was a special camp in California. The United States government built it in 1942. It was used to hold Japanese Americans during World War II. Many of these people were forced to leave their homes on the West Coast. About 120,000 people were held in these camps. More than two-thirds of them were American citizens.

Later, in 1943, the camp was renamed the Tule Lake Segregation Center. It became a high-security camp. Here, people who were thought to be "disloyal" or who caused trouble were kept separate. This included people who protested the unfairness of the camps. At its busiest, Tule Lake held 18,700 people. It was the largest and most talked-about of the ten camps. Over four years, 29,840 people were held there.

After the war, Tule Lake became a place for Japanese Americans waiting to go to Japan. Some had given up their US citizenship because of the pressure. Many later fought in court to get their citizenship back. The camp closed on March 20, 1946. Years later, many people won their court cases. They were able to get their US citizenship restored.

Today, the Tule Lake camp site is a California Historical Landmark. In 2006, it became a National Historic Landmark. In 2008, it was made part of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument. This monument honors important places from the war. In 2019, it became its own special place, the Tule Lake National Monument.

Contents

Why Tule Lake Was Built

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an order. This order, called Executive Order 9066, allowed the military to remove certain groups from the West Coast. Military leaders then ordered nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans to leave their homes. Most of these people were US citizens.

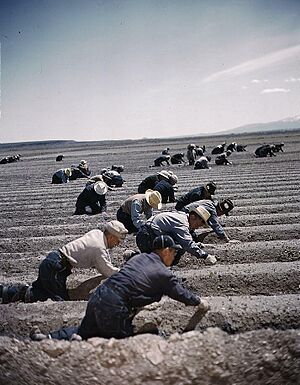

Later studies showed that this decision was based on unfair ideas. It was caused by racism, fear during wartime, and poor leadership. The government built ten large camps in faraway places. They called these camps "relocation centers." Tule Lake opened on May 27, 1942. It first held about 11,800 Japanese Americans. They came from areas like Sacramento, California, and parts of Washington and Oregon.

A newsletter called The Tulean Dispatch was started in June 1942. It stopped in October 1943. This was when Tule Lake became a segregation center. It was the shortest-running newspaper of all the camps.

The Loyalty Questionnaire

In 1943, the government gave out a questionnaire. It was meant to check how "loyal" the Japanese Americans in the camps were. This "loyalty questionnaire" was first for young men who might join the army. But soon, all adults in the camps had to fill it out. Two questions caused a lot of confusion and anger.

Question 27 asked if they would serve in the US armed forces. Many young men felt insulted. The government had taken away their rights. Now it was asking them to risk their lives. Some said they would serve if their families were freed. Others refused to answer at all.

Question 28 asked if they would promise loyalty to the US. It also asked them to give up any loyalty to the Japanese emperor. Many people felt insulted by this question too. Most US citizens had never been to Japan. They felt it was wrong to suggest they were loyal to Japan. Non-citizens, called Issei, worried they would be sent to Japan. They feared an "yes" answer would make Japan see them as enemies. Some people answered "no" to both questions. They did this to protest being held in the camps.

Tule Lake Segregation Center's Role

In 1943, Tule Lake became the Segregation Center. It was used to separate people thought to be disloyal. It also held those who protested the camp conditions. The camp was made into a high-security prison. It quickly became the toughest of the ten camps. People who answered "yes" to the loyalty questions could leave Tule Lake. About 6,500 "loyal" people moved to other camps.

More than 12,000 Japanese Americans were labeled "disloyal." This was because of their answers to the loyalty questions. They were moved to Tule Lake during 1943. The camp became very crowded. Conditions were poor, with bad food and not enough medical care. These problems led to protests by the prisoners.

On November 14, the army took control of Tule Lake. This was after many meetings and protests about the living conditions. The army built more barracks in 1944. This made the population grow to 18,700 people. The camp became a difficult and unsafe place. Army control ended on January 15, 1944. But many prisoners were still upset. They had lived with curfews and searches for months.

In 1944, a lawyer named Wayne M. Collins helped prisoners. He learned about a special jail, called a stockade, at Tule Lake. Prisoners were held there unfairly. Collins used legal threats to get the stockade closed. He had to close it again a year later when it reopened.

In 1944, a new law was passed. It allowed US citizens to give up their citizenship during wartime. Many Japanese Americans at Tule Lake felt angry about how they were treated. They felt there was nothing left for them in the US. About 5,589 people chose to give up their citizenship. Most of these people were at Tule Lake.

After the war ended in 1945, other camps closed. Tule Lake stayed open for those who had given up citizenship. It also held non-citizens who wanted to go to Japan. But many no longer wanted to leave the US. They were held at Tule Lake until their cases could be heard in court. The camp finally closed in March 1946.

Even after release, many who had given up citizenship could not get it back. Wayne M. Collins filed a lawsuit for them. He argued that they had given up citizenship under pressure. After a long legal fight, Collins helped restore citizenship to many in the late 1960s. He also helped 3,000 Japanese Americans stay in the US.

Victory for Tule Lake Draft Resisters

Some Japanese-American men refused to join the army. They wanted to challenge their unfair imprisonment. They also wanted to fight for their rights as US citizens. One important case was United States v. Masaaki Kuwabara. This was the only case of its kind during WWII to be dismissed by a court. It showed that the government had violated his rights.

Judge Louis E. Goodman helped Masaaki Kuwabara. He saw that Kuwabara was treated unfairly because of his Japanese background. The judge ruled against the US government. The government had put Kuwabara in a camp. It had called him an "enemy alien." Then it tried to draft him into the military. Kuwabara refused to join until his rights as an American citizen were returned.

Remembering Tule Lake Today

Japanese-American activists worked to bring attention to the forced removal. They wanted an apology from the US government. The Japanese American Citizens League joined this movement. They helped educate people and gain support.

Pilgrimages to Tule Lake

Since 1974, people have made special trips, called pilgrimages, to Tule Lake. These trips happen every two years around the 4th of July. They are for education and to remember what happened. The movement gained a lot of support. In 1988, Congress passed a law. President Ronald Reagan signed it. This law included an official apology from the government. It also gave money to camp survivors. Another similar law was passed in 1992.

Groups organize these pilgrimages around different themes. They use them to teach others.

- 2000 – 'Honoring our Living Treasures, Forging New Links'

- 2002 – 'As We Revisit the Meaning of Patriotism and Loyalty'

- 2004 – 'Citizens Betrayed'

- 2006 – 'Dignity and Survival in a Divided Community'

- 2009 – 'Shared Remembrances'

- 2010 – 'Untold Stories of Tule Lake'

- 2012 – 'Understanding No-No and Renunciation'

Protecting the Sites

In 2006, President George W. Bush signed a law. It created the Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program. This program provides money to protect and explain these historical sites. It helps preserve the temporary camps and the ten main concentration camps.

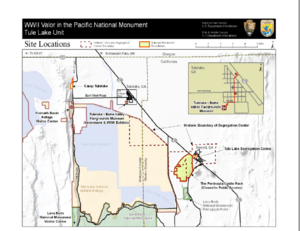

Managing the Monument

The Tule Lake National Monument is managed by two groups. These are the National Park Service (NPS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). The monument covers about 1,391 acres.

The monument has three separate parts. These are the Tule Lake Segregation Center, nearby Camp Tulelake, and a rock formation called the Peninsula/Castle Rock. The NPS manages the Segregation Center alone. Camp Tulelake is managed by both the NPS and USFWS. The USFWS owns the land, and the NPS takes care of the buildings. The USFWS manages the Peninsula/Castle Rock alone.

Famous People Held at Tule Lake

Many people who were held at Tule Lake later became famous.

- Violet Kazue de Cristoforo (1917–2007), a poet.

- Mitsuye Endo (1920–2006), her court case helped Japanese Americans return home.

- Mary Matsuda Gruenewald (1925–2021), a writer of memoirs.

- Taneyuki "Dan" Harada (1923–2020), a painter and computer programmer.

- Hiroshi Honda (1910–1970), an American painter.

- Yamato Ichihashi (1878–1963), one of the first Asian professors in the US.

- Emerick Ishikawa (1920–2006), a weightlifting champion.

- Harvey Itano (1920–2010), a biochemist known for his work on sickle cell anemia.

- Shizue Iwatsuki (1897–1984), a Japanese American poet.

- Hiroshi Kashiwagi (1922–2019), a poet, playwright, and actor.

- Taky Kimura (1924–2021), a martial arts teacher.

- Daisuke Kitagawa (1910–1970), a reverend and priest.

- Mary Koga (1920–2001), a photographer and social worker.

- Tommy Kono (1930–2016), an Olympic gold medalist in weightlifting.

- Joseph Kurihara (1895–1965), who gave up his citizenship.

- Masaaki Kuwabara (1913–1993), who challenged his draft order in court.

- William M. Marutani (1923–2004), a lawyer and judge.

- Bob Matsui (1941–2005), who served many terms in the US House of Representatives.

- Toshiko Mayeda (1923–2004), a Japanese American chemist.

- Tsutomu "Jimmy" Mirikitani (1920–2012), an artist.

- Fujimatsu Moriguchi (1898–1962), an American businessman.

- Sadako Moriguchi (1907–2002), an American businesswoman.

- Tomio Moriguchi (born 1936), an American businessman and civil rights activist.

- Tomoko Moriguchi-Matsuno (born 1945), an American businesswoman.

- Pat Morita (1932–2005), an actor famous for The Karate Kid films.

- Jimmy Murakami (1933–2014), an animator and director.

- George Nakano (born 1935), a former California State Assemblyman.

- Alan Nakanishi (born 1940), a California politician.

- James K. Okubo (1920–1967), a US Army soldier and Medal of Honor recipient.

- James Otsuka (1921–1984), who refused to fight in WWII.

- Otokichi Ozaki (1904–1983), a poet.

- James Sakoda (1916–2005), a psychologist.

- Minako Sasaki (1943–2023), an actress.

- Toshiyuki Seino (born 1938), an American judo athlete.

- Joan Shigekawa (born 1936), a film producer and arts leader.

- Yuki Shimoda (1921–1981), an actor.

- Sab Shimono (born 1937), an actor.

- Hana Shimozumi (1893–1978), an American singer.

- Noboru Shirai, author of "Tule Lake: An Issei Memoir."

- Robert Mitsuhiro Takasugi (1930–2009), the first Japanese-American federal judge.

- George Takei (born 1937), an American actor famous for Star Trek.

- George T. Tamura (1927–2010), an artist.

- Kazue Togasaki (1897–1992), one of the first Japanese-American women doctors.

- Teiko Tomita (1896–1990), a tanka poet.

- Taitetsu Unno (1930–2014), a Buddhist scholar and author.

- Harry Urata (1917–2009), a music teacher.

- Jimi Yamaichi, a Tule Lake survivor and activist.

- Koho Yamamoto (born 1922), an American artist.

- Takuji Yamashita (1874–1959), an early civil rights leader.

- Kenneth Yasuda (1914–2002), a scholar and translator.

- David Ikeda (1920–2015), a painter and store owner.

What to Call the Camps

There has been a lot of discussion about what to call Tule Lake and other camps. People have used terms like "relocation camp" and "internment camp." But many activists and scholars believe "concentration camp" is more accurate. They say the government used softer words to hide the truth.

In 1998, a museum exhibit used the term "concentration camps." At first, some groups disagreed. But Japanese American and Jewish American leaders met. They agreed on a shared understanding. They said a concentration camp is a place where people are held just because of who they are. They noted that Nazi camps were much worse, with torture and killings. But they agreed that all concentration camps share one thing. People in power remove a minority group, and society lets it happen.

In 2012, the Japanese American Citizens League agreed. They called for using "truthful and accurate terms." They wanted to stop using misleading words. They said these words were created to cover up the denial of rights. They wanted to describe the forced conditions and racism against 120,000 innocent people.

See also

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |