California water wars facts for kids

The California water wars were big disagreements between the city of Los Angeles and farmers in the Owens Valley of Eastern California. These fights were all about who had the right to use water.

As Los Angeles grew in the late 1800s, it needed more and more water. Frederick Eaton, who was the mayor of Los Angeles, realized that water could flow from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles through a long water channel. William Mulholland led the building of this aqueduct, which finished in 1913. Los Angeles got the water rights through clever tricks and secret plans.

Since 1913, the Owens River's water was sent to Los Angeles. This caused big problems for the valley's farms and economy. By the 1920s, so much water was taken that farming became very hard. Because of this, farmers tried to destroy the aqueduct in 1924. But Los Angeles won, and the water kept flowing. By 1926, Owens Lake at the bottom of Owens Valley was completely dry because its water was diverted.

Los Angeles kept needing more water. In 1941, the city started taking water that used to flow into Mono Lake, which is north of Owens Valley. This made Mono Lake's water level drop, threatening the birds that lived there. From 1979 to 1994, David Gaines and the Mono Lake Committee went to court against Los Angeles. These legal battles made Los Angeles stop taking water from around Mono Lake. The lake has now started to rise back to a level that can support its wildlife.

Contents

Owens Valley Before the Water Wars

The Paiute natives were the first people to live in the Owens Valley. They used special ditches to water their crops.

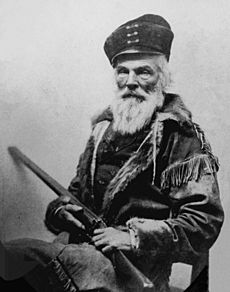

In 1833, Joseph R. Walker led the first known trip into the area that would become the Owens Valley. He saw that the valley's soil was not as good as other places. He also noticed that water from the mountains disappeared into the dry desert ground. After the United States took control of California in 1848, the government started to survey the valley. An early report incorrectly said the Owens Valley was "worthless to the White Man."

Settlers and Land Rules

In 1861, Samuel Bishop and other ranchers started raising cattle in the Owens Valley. The valley had lots of grass. These ranchers soon had conflicts with the Paiute people over land and water. Most of the Paiutes were forced out of the valley by the U.S. Army in 1863 during the Owens Valley Indian War.

Many settlers came to the area hoping to find riches from mining. But the water from the Owens River also made farming and raising animals appealing. The Homestead Act of 1862 let pioneers claim up to 160 acres (65 ha) of land for a small fee. This law was meant to create many small farms.

Later, the Desert Land Act of 1877 allowed people to claim more land, up to 640 acres (259 ha). This was to encourage more settlers. By the mid-1890s, most of the land in the Owens Valley had been claimed. However, many of these claims were made by people who just wanted to sell the land later. This slowed down the building of canals and ditches needed for farming.

Farming and Water Use

Before the Los Angeles Aqueduct, most of the 200 miles (320 km) of canals and ditches in the Owens Valley were in the northern part. The southern part was mostly used for raising livestock. The early irrigation systems often put too much water on the soil, making it hard to grow crops. These systems also lowered the water level in Owens Lake. This problem got much worse later when Los Angeles started taking water. By the early 1900s, the northern Owens Valley began focusing on growing fruit, poultry, and dairy products.

Building the Los Angeles Aqueduct

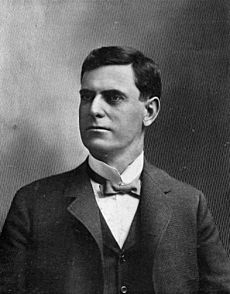

Frederick Eaton and William Mulholland were key figures in the California water wars. They were friends and had worked together at the Los Angeles Water Company. In 1898, Eaton became mayor of Los Angeles. He helped the city take control of the Water Company in 1902. Mulholland then became the superintendent of the new Los Angeles Water Department.

Vision for a Growing City

Eaton and Mulholland dreamed of a much bigger Los Angeles. But the city's growth was limited by its water supply. Mulholland famously said, "If you don't get the water, you won't need it."

They realized that the Owens Valley had a lot of water flowing from the Sierra Nevada mountains. They saw that a water channel could carry this water to Los Angeles using gravity.

Getting Water Rights: A Secret Plan

At the start of the 1900s, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation planned to build an irrigation system for Owens Valley farmers. This would have stopped Los Angeles from taking the water.

From 1902 to 1905, Eaton and Mulholland used secret methods to get water rights and block the Bureau of Reclamation. Joseph Lippincott, an engineer for the Bureau, worked closely with Eaton. Eaton got inside information about water rights and could suggest actions to the Bureau that helped Los Angeles. Lippincott also secretly advised Los Angeles on how to get water rights.

In 1905, Eaton offered high prices to buy land in Owens Valley. This made some local people in Inyo County suspicious. Eaton bought land as a private citizen, hoping to sell it back to Los Angeles for a big profit. He later claimed he gave all his water rights to the city without being paid, except for some cattle and mountain grazing land. Eaton moved to Owens Valley to become a cattle rancher on the land he bought. He always said he did not act in a dishonest way.

Mulholland also misled the public in Los Angeles. He said there was much less local water available for the city's growth than there actually was. He also misled Owens Valley residents. He said Los Angeles would only use extra water flows, but he planned to take all the water rights. He wanted to fill the underground water storage of the San Fernando Valley.

By 1907, Eaton was busy getting important water rights. He also went to Washington to meet with President Theodore Roosevelt's advisors. He tried to convince them that the water from the Owens River would be more useful flowing to Los Angeles homes than being used on Owens Valley farms.

The fight over Owens River water became a political issue in Washington. Los Angeles needed permission to build the aqueduct across federal land. California Senator Frank Flint proposed a bill to allow this. But Congressman Sylvester C. Smith from Inyo County was against it. He argued that watering Southern California was not more important than watering Owens Valley. President Roosevelt eventually decided in favor of Los Angeles.

Some historians say that Los Angeles paid an unfairly low price for the farmers' land in Owens Valley. The price Los Angeles was willing to pay for water from other sources was much higher than what the farmers received. Farmers who waited until 1930 to sell got the best prices. But most farmers sold their land between 1905 and 1925 for less. Still, selling their land brought farmers more money than if they had kept farming. No sales were made under the threat of the government forcing them to sell.

The aqueduct project was presented to Los Angeles citizens as vital for the city's growth. But the public did not know that the first water would be used to water the San Fernando Valley to the north, which was not part of the city yet. The San Fernando Valley was perfect for water storage because its underground water supply could hold water without it evaporating. A city rule said that Los Angeles could not sell or lease its water without a two-thirds vote from citizens. This rule was avoided by adding a large part of the San Fernando Valley to the city. This also allowed Los Angeles to borrow more money to pay for the aqueduct.

A group of rich investors, called the San Fernando land syndicate, bought large areas of land in the San Fernando Valley. They had secret information from Eaton. This group included friends of Eaton, like Harrison Gray Otis. The syndicate worked hard to get the public to vote yes on the bond issue that paid for the aqueduct. Some reports say they even dumped water from Los Angeles reservoirs into the sewers to create a fake water shortage. They also published scary articles in the Los Angeles Times newspaper, which Otis owned. However, some historians doubt water was dumped from reservoirs. The syndicate did get the business community to support the aqueduct. Their land purchases were public by the time people voted on the aqueduct.

Building the Giant Aqueduct

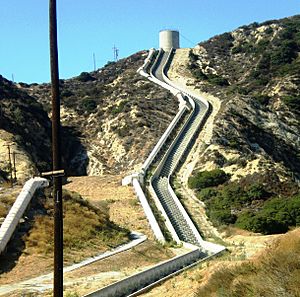

From 1907 to 1913, Mulholland oversaw the building of the aqueduct. The 233-mile (375 km) Los Angeles Aqueduct opened in November 1913. It needed over 2,000 workers and 164 tunnels. Mulholland's granddaughter said the project was as complex as building the Panama Canal. Water from the Owens River reached a reservoir in the San Fernando Valley on November 5, 1913. At the opening ceremony, Mulholland said his famous words: "There it is. Take it."

After the aqueduct was finished in 1913, the San Fernando investors demanded so much water from the Owens Valley that it started to turn from a green area into a desert. Mulholland could not get more water from the Colorado River, so he decided to take all the available water from the Owens Valley.

Farmers Fight Back

In 1923, farmers and ranchers formed a group to work together. It was led by Wilfred and Mark Watterson, who owned the Inyo County Bank. Los Angeles used disagreements among some farmers to get important water rights from this group. After these water rights were secured, water flowing into Owens Lake was greatly reduced. This caused the lake to dry up by 1924.

By 1924, farmers and ranchers rebelled. Mulholland made some moves that angered them, and the farmers responded by damaging Los Angeles property. Finally, a group of armed ranchers took control of the Alabama Gates and blew up part of the aqueduct system. This allowed water to flow back into the Owens River.

In August 1927, when the conflict was at its peak, the Inyo County bank failed. This greatly weakened the valley's resistance. An investigation showed that money was missing from the bank. The Watterson brothers were charged with misusing money and found guilty. Since all local businesses used their bank, its closing left people with very little money. The brothers claimed they did it to help Owens Valley against Los Angeles. Many people in Inyo County believed this. The bank's failure wiped out the life savings of many people, including money they got from selling their homes and ranches to Los Angeles.

With the resistance broken and the Owens Valley economy ruined, the attacks on the aqueduct stopped. The City of Los Angeles started repair and maintenance programs for the aqueduct. This created some local jobs. Los Angeles water employees were even paid a month in advance to help. But many businesses still had to close.

The End of Owens Valley Farming

The City of Los Angeles kept buying private land and water rights to meet its growing needs. By 1928, Los Angeles owned 90 percent of the water in Owens Valley. Farming in the region was practically over.

The Second Aqueduct and New Rules

In 1970, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) finished building a second aqueduct. In 1972, the agency started taking more surface water and pumping underground water. This was hundreds of thousands of acre-feet each year. As a result, Owens Valley springs and wet areas dried up, and plants that depended on underground water began to die.

Protecting Owens Valley's Nature

LADWP had not fully studied how pumping groundwater would affect the environment. So, Inyo County sued Los Angeles under California's environmental laws. Los Angeles did not stop pumping water. They submitted two environmental reports, but courts rejected both as not good enough.

In 1991, Inyo County and Los Angeles signed the Inyo-Los Angeles Long Term Water Agreement. This agreement said that groundwater pumping must be managed to avoid major harm to the environment. It also had to provide a steady water supply for Los Angeles. In 1997, Inyo County, Los Angeles, the Owens Valley Committee, and the Sierra Club signed another agreement. This one said that the lower Owens River would have water flowing in it again by June 2003. This was to help fix some of the damage to the Owens Valley.

Even with these agreements, studies from 2003 showed that plants in the valley that depend on groundwater, like alkali meadows, were still being harmed. Also, Los Angeles did not put water back into the lower Owens River by the 2003 deadline. In December 2003, LADWP settled a lawsuit brought by California's top lawyer, Bill Lockyer, the Owens Valley Committee, and the Sierra Club. Under this agreement, new deadlines were set for the Lower Owens River Project. LADWP was supposed to return water to the lower Owens River by 2005. This deadline was also missed. But on December 6, 2006, a ceremony was held to restart the flow of water down the 62-mile (100 km) river. This was at the same spot where William Mulholland had opened the aqueduct that stopped the river's flow. David Nahai, president of the L.A. Water and Power Board, changed Mulholland's famous words from 1913 and said, "There it is ... take it back."

However, groundwater pumping continues at a faster rate than the water can naturally refill the underground supply. This is slowly turning parts of the Owens Valley into a desert.

Saving Mono Lake

By the 1930s, Los Angeles needed even more water. LADWP started buying water rights in the Mono Basin, which is north of the Owens Valley. An extension to the aqueduct was built. This included amazing engineering, like tunneling through the Mono–Inyo Craters, which is an active volcanic area. By 1941, the extension was finished. Water from various creeks, like Rush Creek, was sent into the aqueduct. To follow California water laws, LADWP set up a fish hatchery on Hot Creek, near Mammoth Lakes, California.

The diverted creeks had previously fed Mono Lake, which is a lake with no outlet. Mono Lake was a very important place for birds, especially gulls and migratory birds that nested there. Because the creeks were diverted, the water level in Mono Lake started to fall. This exposed strange rock formations called tufa. The water also became saltier and more alkaline. This threatened the tiny brine shrimp that lived in the lake. Changes in saltiness made the shrimp smaller and less able to have babies. This put the shrimp at risk, and also the birds that nested on two islands (Negit Island and Paoha Island) in the lake. Falling water levels started to create a land bridge to Negit Island. This allowed predators to reach the bird eggs for the first time.

People Fight to Save the Lake

In 1974, David Gaines began studying the plants and animals of Mono Lake. In 1975, while at Stanford, he got others interested in the lake's ecosystem. This led to a 1977 report that showed the dangers caused by the water diversion. In 1978, the Mono Lake Committee was formed to protect Mono Lake. The Committee and the National Audubon Society sued LADWP in 1979. They argued that taking the water went against the idea that natural resources should be managed for everyone's benefit. The court case reached the California Supreme Court by 1983, which ruled in favor of the Committee. More lawsuits started in 1984, claiming LADWP did not follow state laws protecting fish.

Mono Lake Starts to Recover

Finally, all the legal battles were decided in 1994 by the California State Water Resources Control Board. The hearings lasted 44 days. In its ruling, the Board set important rules for protecting Mono Lake and restoring its ecosystem. LADWP was told to release water into Mono Lake to raise its level 20 feet (6.1 m) higher than it was then. At that time, the lake was 25 feet (7.6 m) lower than it was in 1941. As of 2011, the water level in Mono Lake has risen 13 feet (4.0 m) of the required 20 feet (6.1 m). Los Angeles made up for the lost water by using state-funded conservation and recycling projects.

Water Challenges in Central California

In February 2014, after three years of less-than-normal rainfall, California faced a very serious drought. Fish in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta were in huge trouble. This was due to decades of large amounts of water being sent from Northern California to the south. Bill Jennings, a director of a fishing protection group, said that "Fisheries... people and economic prosperity of northern California are at grave risk." Half a million acres of farmland in the Central Valley were supposedly in danger of drying up because of the drought.

On February 5, 2014, the House of Representatives passed a bill to send more water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta to the Central Valley. This bill would stop recent efforts to restore the San Joaquin River since 2009. These efforts had been won after 18 years of legal battles. Democratic Senators Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer suggested emergency drought help of $300 million. They also wanted to speed up environmental checks for water projects. This would give state and federal officials more freedom to move water south, from the delta to farms in the San Joaquin Valley.

On February 14, 2014, President Barack Obama visited near Fresno. He announced $170 million in new plans. This included $100 million for ranchers whose animals were suffering and $60 million to help food banks. Obama joked about California's long and sometimes angry history of water politics. He said, "I'm not going to wade into this. I want to get out alive on Valentine's Day."

Stories and Films About the Water Wars

The California water wars were a main topic in Cadillac Desert. This was a 1984 book by Marc Reisner about land development and water rules in the western United States. The book was made into a four-part documentary with the same name in 1997.

The 1974 film Chinatown was inspired by the California water wars. It shows a made-up version of the conflict as a main part of its story.

Images for kids

-

The Los Angeles Aqueduct in the Owens Valley.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |