William Mulholland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Mulholland

|

|

|---|---|

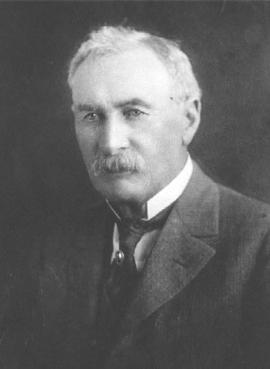

Mulholland in 1924

|

|

| Born |

William Mulholland

September 11, 1855 Belfast, Ireland, UK

|

| Died | July 22, 1935 (aged 79) Los Angeles, California, US

|

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery, Glendale, California |

| Citizenship | British/Irish, American |

| Education | O'Connell school |

| Occupation | Civil engineer |

| Years active | 1878–1929 |

| Employer | Bureau of Water Works and Supply |

| Known for | Building the water system of Los Angeles |

| Successor | Harvey Van Norman |

| Spouse(s) |

Lillie Ferguson

(m. 1890) |

William Mulholland (born September 11, 1855 – died July 22, 1935) was an Irish American engineer who taught himself everything he knew. He was very important for building the water system that helped Los Angeles grow into the biggest city in California. Mulholland led the group that later became the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. He designed and watched over the building of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. This was a 233-mile (375 km) long system that brought water from the Owens Valley to the San Fernando Valley.

The aqueduct caused big disagreements known as the California Water Wars. In March 1928, Mulholland's career ended when the St. Francis Dam broke. This happened just 12 hours after he and his helper had checked it for safety.

Contents

Early Life

William Mulholland was born in Belfast, Ireland, which was part of the United Kingdom. His parents, Hugh and Ellen Mulholland, were from Dublin. They moved back to Dublin a few years after William was born. His younger brother, Hugh Jr., was born in 1856. When William was born, his father worked as a guard for the Royal Mail.

In 1862, when William was seven, his mother died. Three years later, his father married again. William went to O'Connell School in Dublin. He was taught by the Christian Brothers. After his father punished him for getting bad grades, Mulholland ran away to sea.

At 15, Mulholland joined the British Merchant Navy. For the next four years, he worked as a sailor on a ship called Gleniffer. He crossed the Atlantic Ocean at least 19 times, visiting ports in North America and the Caribbean. In 1874, he got off the ship in New York. He then traveled west to Michigan. There, he worked on a Great Lakes freighter in the summer and in a lumber camp in the winter.

He almost lost a leg in a logging accident. After that, he moved to Ohio and worked as a handyman. Mulholland met up with his brother Hugh again. In December 1876, they secretly boarded a ship in New York that was going to California. They were found in Panama and had to leave the ship. They then walked over 47 miles (76 km) through the jungle to Balboa. Mulholland finally arrived in Los Angeles in 1877.

Starting Work in Los Angeles

When Mulholland arrived in Los Angeles, about 9,000 people lived there. He quickly thought about going back to sea because it was hard to find work. On his way to the port at San Pedro to find a ship, he took a job digging a well.

After a short time in Arizona, where he looked for gold and worked on the Colorado River, he got a job from Frederick Eaton. He became a Deputy Zanjero (water distributor) for the new Los Angeles City Water Company (LACWC). In the past, during Spanish and Mexican times, water was brought to the Pueblo de Los Angeles in a big open ditch called the Zanja Madre. The person who took care of this ditch was called a zanjero.

In 1880, Mulholland was in charge of putting in the first iron water pipeline in Los Angeles. Mulholland left the LACWC for a short time in 1884 but came back in December. He left again in 1885 and worked for another water company. In 1886, he returned to the LACWC. In October, he became an American citizen. By the end of that year, he was made the superintendent of the LACWC. In 1898, the city of Los Angeles decided not to continue its contract with the LACWC.

Four years later, the Los Angeles Water Department was created, and Mulholland became its superintendent. In 1911, the Water Department changed its name to the Bureau of Water Works and Supply. Mulholland was named its chief engineer. In 1937, two years after Mulholland died, this bureau joined with another one to form the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). This agency still manages the city's water today.

The Los Angeles Aqueduct

Mulholland believed Los Angeles could become much bigger. But the city needed more water to grow because it has a semi-arid climate, meaning it doesn't get much rain. Mulholland famously said, "If you don't get the water, you won't need it," showing how important water was.

Mulholland shared this idea of a bigger Los Angeles with Frederick Eaton, who was the mayor of Los Angeles from 1898 to 1900. They both worked together in the private Los Angeles Water Company in the 1880s. In 1886, Eaton became the City Engineer, and Mulholland became the superintendent of the Water Company. When Eaton became mayor, he helped the city take control of the Water Company in 1902.

When the company became the Los Angeles Water Department, Mulholland stayed on as superintendent. This was because he knew so much about the water system. The city quickly grew as Mulholland's projects began to bring water to dry land. In just ten years, the city's population doubled from 50,000 in 1890 to over 100,000 in 1900. Ten years later, it had tripled to almost 320,000.

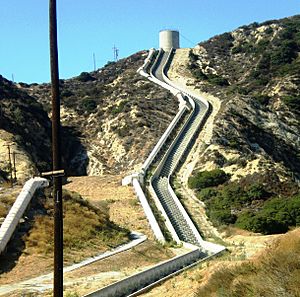

To make this growth possible, Eaton and Mulholland realized that a lot of water flowed from the Sierra Nevada mountains into the Owens Valley. They thought this water could be brought to Los Angeles using a gravity-fed aqueduct.

From 1902 to 1905, Eaton, Mulholland, and others worked to make sure Los Angeles got the water rights in the Owens Valley. Mulholland did not tell the public in Los Angeles how much water the city already had. He also did not fully explain to Owens Valley residents that Los Angeles planned to use all the water rights, not just the unused water.

In 1906, the Los Angeles Board of Water Commissioners made Mulholland the Chief Engineer of the Los Angeles Aqueduct project. From 1907 to 1913, Mulholland led the building of the aqueduct. The 233-mile (375 km) Los Angeles Aqueduct opened in November 1913. At its busiest, the project needed 3,900 workers. They had to dig 164 tunnels. Building started in 1908. The project was so complex that people compared it to building the Panama Canal. Water from the Owens River reached a reservoir in the San Fernando Valley on November 5, 1913. At a ceremony that day, Mulholland said his famous words about this amazing engineering achievement: "There it is. Take it."

The aqueduct brings water from the Owens Valley in the Eastern Sierra mountains to water farms and store water in the San Fernando Valley. When the aqueduct was built, the San Fernando Valley was not part of the city. The San Fernando Valley was a good place for water storage because its underground water supply (aquifer) could hold water without it evaporating. To use this water for farming, a rule in the Los Angeles City Charter had to be worked around. This rule said that the city's water could not be sold or used without two-thirds of voters agreeing. This rule was avoided by adding a large part of the San Fernando Valley to the city.

Mulholland knew that adding this land would allow Los Angeles to borrow more money, which was needed to pay for the aqueduct. By 1915, the first areas were added to the city. By 1926, the land area of Los Angeles had doubled, making it the largest city in the United States by size. Areas that joined the city's water system included Owensmouth (Canoga Park) (1917), Laurel Canyon (1923), Lankershim (1923), Sunland (1926), La Tuna Canyon (1926), and the city of Tujunga (1932). The connection between water and the fast growth of Los Angeles is shown in the 1974 film Chinatown.

The water from Mulholland's aqueduct also changed farming. Farmers started growing crops like corn, beans, squash, and cotton, instead of just wheat. They also grew fruit trees like apricots, persimmons, and walnuts, and many citrus groves of oranges and lemons. These farms stayed in the city until new buildings and neighborhoods took their place. A few small farm areas still exist, like the groves at the Orcutt Ranch Park and the CSUN campus.

Professional Achievements

Mulholland, who learned engineering on his own, was the first American civil engineer to use a special method called hydraulic sluicing to build a dam. He used this method when building the Silver Lake Reservoir in 1906. This new way of building dams got attention from engineers and dam builders across the country. Government engineers used this method when building the Gatun Dam in the Panama Canal Zone, where Mulholland was a helper.

In 1914, the University of California, Berkeley gave Mulholland an honorary doctorate degree. The words on his diploma meant, "He broke the rocks and brought the river to the thirsty land." Mulholland became more and more famous. His offices were once on the top floor of Sid Grauman's Million Dollar Theater. Some even thought he might become mayor of Los Angeles. When asked if he would run for mayor, he joked, "I'd rather give birth to a porcupine backward."

Owens Valley Water Conflict

After the Los Angeles Aqueduct was finished, the San Fernando Valley needed so much water from the Owens Valley that the valley began to turn from a green area into a desert. Mulholland could not get more water from the Colorado River, so he decided to take all the available water from the Owens Valley.

By 1924, farmers and ranchers in the Owens Valley were very angry. They started to fight back against Los Angeles. Mulholland's actions led to threats from local farmers and the destruction of Los Angeles property. A group of armed ranchers took control of the Alabama Gates and blew up the aqueduct at Jawbone Canyon. This allowed water to flow back into the Owens River.

More acts of violence against the aqueduct continued that year. This led to a big event where opponents took over a key part of the aqueduct. For four days, they completely stopped the water flow to Los Angeles. State and local leaders did not act, and newspapers showed the Owens Valley farmers and ranchers as underdogs. Eventually, Mulholland and the city leaders had to talk and try to find a solution. Mulholland was quoted saying, in anger, that he "half-regretted the demise of so many of the valley's orchard trees, because now there were no longer enough trees to hang all the troublemakers who live there."

In 1927, during the height of the water conflict, the Inyo County Bank failed. The economy of Owens Valley collapsed, and the attacks stopped. The city of Los Angeles started programs to repair and maintain the aqueduct. This helped create some jobs in the area.

St. Francis Dam Collapse

Mulholland's career basically ended on March 12, 1928. This was when the St. Francis Dam broke. It happened just twelve hours after he and his assistant, Harvey Van Norman, had personally checked the dam. In seconds, a huge part of the dam broke, and 12.4 billion gallons (47 million cubic meters) of water rushed down San Francisquito Canyon. The water was 140 feet (43 meters) high and moved at 18 miles per hour (29 km/h). It destroyed Powerhouse Number Two, a power plant, and killed 64 of the 67 workers and their families living there.

The water flowed south and into the Santa Clara riverbed. It flooded parts of what are now Valencia and Newhall. Following the river, the water continued west, flooding towns like Castaic Junction, Piru, Fillmore, Bardsdale, and Santa Paula in Ventura County. The flood was almost two miles (3 km) wide. It was still moving at 5 miles (8 km) per hour when it reached the ocean at 5:30 am. It carried victims and debris into the Pacific Ocean near Montalvo, 54 miles (87 km) from the dam. Many bodies that were washed out to sea were found, some as far south as the Mexican border. Others were never found.

Santa Paula suffered some of the worst damage, especially the low areas near the river. In many places, only foundations or rubble showed where homes had been. Rescue efforts were difficult because a thick layer of mud covered the area.

Rescue teams worked for days to find bodies and clear the mud from the flood's path. The total number of deaths is thought to be at least 431. At least 108 of those who died were children.

Mulholland took full responsibility for what has been called the worst human-made disaster in the US in the 20th century. He retired in November 1928. During the investigation by the Los Angeles Coroner, Mulholland said, "this inquest is very painful for me to have to attend but it is the occasion of that is painful. The only ones I envy about this whole thing are the ones who are dead." Later, he added, "Whether it is good or bad, don't blame anyone else, you just fasten it on me. If there was an error in human judgment, I was the human, I won't try to fasten it on anyone else."

The jury decided that the disaster happened because of a mistake in judging if the ground was stable enough for the dam. They also pointed to mistakes in public policy. They said Mulholland should not be held criminally responsible. Their verdict stated, "We, the Jury, find no evidence of act of criminal act or intent on the part of the Board of Water Works and Supply of the City of Los Angeles, or any engineer or employee in the construction or operation of the St. Francis Dam..."

However, some critics pointed out that another dam Mulholland had advised on also broke. The city also stopped a dam project in San Gabriel before it was finished. Mulholland had made the St. Francis Dam 20 feet (6 meters) taller after building started, without making the base wider to match.

Later Life and Death

Mulholland spent the rest of his life mostly out of public view, deeply saddened by the tragedy. In retirement, he started writing his life story but never finished it. Shortly before he died, he was asked for advice on the Hoover Dam and Colorado River Aqueduct projects. He died in 1935 from a stroke. He is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale, California.

Legacy

In Los Angeles, the Mulholland Dam in the Hollywood Hills, Mulholland Drive, Mulholland Highway, and Mulholland Middle School are all named after William Mulholland.

See also

In Spanish: William Mulholland para niños

In Spanish: William Mulholland para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |