Mono–Inyo Craters facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mono–Inyo Craters |

|

|---|---|

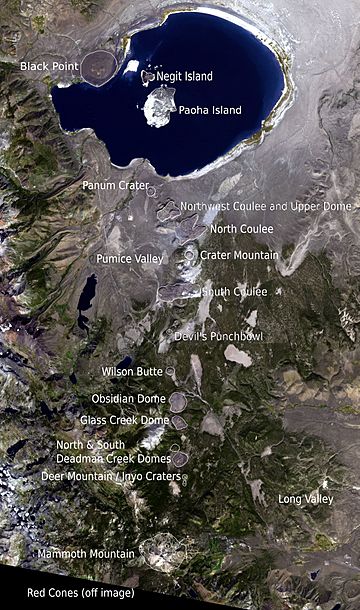

Annotated satellite image of the chain

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Crater Mountain |

| Elevation | 9,172 ft (2,796 m) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 25 mi (40 km) |

| Geography | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | Eastern California |

| County | Mono |

| Settlement | Mammoth Lakes, California |

| Range coordinates | 37°53′N 119°0′W / 37.883°N 119.000°W |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | About 40,000 years |

| Type of rock | Lava domes, cinder cones |

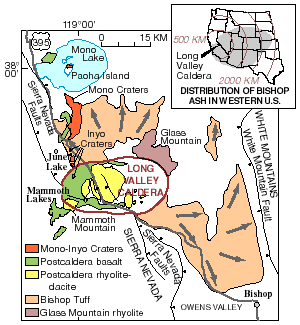

The Mono–Inyo Craters are a chain of volcanoes in Mono County, Eastern California. This chain includes craters, domes (round hills formed by lava), and lava flows. It stretches about 25 miles (40 km) from the northwest shore of Mono Lake down to the south of Mammoth Mountain.

The northern part of the chain is called the Mono Lake Volcanic Field. It has two volcanic islands in Mono Lake and a volcano shaped like a cone (called a cinder cone) on the lake's northwest shore. Most of the Mono Craters are volcanoes that formed from steam explosions. Later, these were either blocked or covered by rhyolite domes and lava flows. The Inyo volcanic chain makes up the southern part, with steam explosion pits and rhyolite lava flows and domes. The very southern end has steam vents (fumaroles) and explosion pits on Mammoth Mountain, plus some cinder cones called the Red Cones.

Volcanic activity in this area started a long time ago, between 400,000 and 60,000 years ago. Mammoth Mountain was formed during this early period. The Mono Craters were created by many eruptions from 40,000 to 600 years ago. The Inyo volcanic chain formed from eruptions between 5,000 and 500 years ago. The Red Cones were built by lava flows 5,000 years ago, and explosion pits on Mammoth Mountain appeared in the last 1,000 years. The most recent activity was about 250 years ago, when Paoha Island in Mono Lake was pushed up. These eruptions likely came from smaller pockets of molten rock, not one giant magma chamber like the one that caused the huge Long Valley Caldera eruption 760,000 years ago. Over the past 3,000 years, eruptions have happened every 250 to 700 years. In 1980, earthquakes and ground uplift showed that the area was becoming active again.

People have lived in this region for centuries. The Mono Paiutes collected obsidian (a type of volcanic glass) from the Mono–Inyo Craters to make sharp tools and arrowheads. Even today, this glassy rock is taken for cleaning products and garden decorations. From the late 1800s to early 1900s, Mono Mills processed wood from the volcanoes for the nearby gold rush town of Bodie. In 1941, a water tunnel was built under the Mono Craters to send water from Mono Lake to the Los Angeles Aqueduct system. Since 1984, the Mono Lake Volcanic Field and much of the Mono Craters have been protected as part of the Mono Basin National Scenic Area. The United States Forest Service manages the area. You can enjoy many activities here, like hiking, bird watching, canoeing, skiing, and mountain biking.

Contents

Exploring the Mono–Inyo Craters

Where are the Craters?

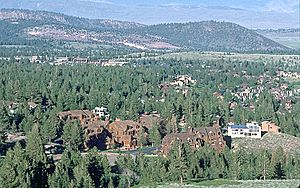

The Mono–Inyo Craters are a chain of volcanoes in Eastern California. They sit along a narrow line that runs north to south, starting from the north shore of Mono Lake and going through the western part of the Long Valley Caldera, south of Mammoth Mountain. This area is inside the Inyo National Forest and Mono County. The closest town is Mammoth Lakes. The craters are part of the larger Great Basin region.

The Mono Craters

The Mono Craters are a chain of at least 27 volcanic domes. These domes are like rounded hills made of hardened lava. The chain is about 10.5-mile (17 km) long. There are also three large lava flows, called coulees, and many explosion pits. The domes form a curve that points west, located south of Mono Lake. The tallest of the Mono Craters is Crater Mountain, which is 9,172 feet (2,796 m) high. It rises about 2,400 feet (730 m) above Pumice Valley to the west. Other volcanic features are found in Mono Lake, like Paoha and Negit Islands, and on its north shore, like Black Point.

The Inyo Volcanic Chain

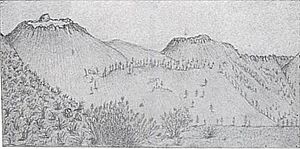

The Inyo volcanic chain stretches about 6 miles (10 km) from Wilson Butte to the main Inyo Craters. The Inyo Craters are open pits in a forest. They are about 600 feet (180 m) wide and 100 to 200 feet (30 to 60 m) deep, and each has small ponds at the bottom. A bit north of these, there's another explosion pit on top of Deer Mountain. Further north, there are five lava domes, including Deadman Creek Dome, Glass Creek Dome, and Obsidian Dome. These domes are made of gray rhyolite, light and bubbly pumice, and black obsidian.

The Red Cones

South of the Inyo volcanic chain, you'll find other features linked to the underground cracks (called dikes) that created the craters, volcanoes, and lava flows. These include fault scarps (steep slopes formed by faults) up to 20 feet (6 m) high, and cracks in the earth. One famous crack is "Earthquake Fault," which is up to 10 feet (3 m) wide and cuts 60 to 70 feet (18 to 21 m) deep into glassy rhyolite lava. This crack formed when the ground stretched as the Inyo dike pushed up. Stairs that once led to the bottom of this crack were removed after being damaged by earthquakes in 1980.

Several explosion pits related to the Mono–Inyo chain are on Mammoth Mountain. The Red Cones, located south of Mammoth Mountain, are small, reddish-brown cinder cones. They are the southernmost part of the Mono–Inyo Craters volcanic chain.

Weather and Wildlife

The Mono–Inyo Craters are in the Great Basin Desert area. The Mono Basin desert gets about 14 inches (36 cm) of rain each year. Near Mammoth Lakes, close to the Inyo volcanic chain, it gets more rain, about 23 inches (58 cm) annually. Temperatures in Mono Basin range from winter lows of 20 to 28 °F (−7 to −2 °C) to summer highs of 75 to 84 °F (24 to 29 °C). Near the Inyo volcanic chain and Mammoth Lakes, winter lows are 16 to 21 °F (−9 to −6 °C) and summer highs are 70 to 78 °F (21 to 26 °C).

Most of the Mono Craters' surface is bare, but their slopes are covered by Jeffrey pine forests and some green plants. Pumice Valley, to the west, is covered by sagebrush plants. The soil is mostly deep pumice, which doesn't hold water well. Jeffrey pine trees have a special relationship with fungi in the soil, which helps the trees get water and nutrients. Jeffrey pine forests also grow around the Inyo volcanic chain and Mammoth Mountain. Animals like Mule deer, coyotes, black bears, yellow-bellied marmots, raccoons, and mountain lions live in these forests.

How Volcanoes Form Here

Panum Crater is the northernmost volcano in the chain and shows how these volcanoes typically form. It has two main parts: an outer ring (a classic crater) and an inner dome made of rhyolite, pumice, and obsidian. The heat from the magma (molten rock) under Panum Crater turned groundwater into steam, causing an explosion that created the outer ring before lava even reached the surface. Then, lava oozed out to form the inner dome. Other Mono Craters formed this way too, but their domes grew larger than their outer crater rings. These domes have steep sides and are surrounded by piles of broken, sharp rocks. Devil's Punch Bowl, an explosion pit south of the main domes, is an example of a volcano that stopped forming at an earlier stage. It's 1,200-foot (370 m) wide and 140-foot (43 m) deep, with a smaller glass dome on its floor.

The large North and South Coulee and the smaller Northwest Coulee are made of obsidian-rich rhyolite. These formed from slow-moving lava that had a thin, fragile crust. When the lava stopped moving, it created steep, tongue-shaped piles of sharp, angular rock, usually 200 to 300 feet (60 to 90 m) thick, with piles of scree (loose rocks) at their base. South Coulee is about 2.25 miles (3.6 km) long and 0.75 miles (1.2 km) wide, making it the largest Mono Craters coulee by volume. North Coulee is almost as big and flows mostly to the east. Northwest Coulee is located northwest of North Coulee. Interestingly, permanent pockets of ice from melted snow have been found deep inside these coulees and domes.

Geology of the Area

Volcanic History

The Mono–Inyo chain of craters is in east-central California, running roughly parallel to the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Volcanic activity and earthquakes in this part of California happen because of two main geological processes: the Pacific Plate moving northwest past the North American Plate along the San Andreas Fault near the coast, and the Earth's crust stretching from east to west, which formed the Basin and Range Province. In the Long Valley area, where the craters are, this stretching affects the thick, stable crust of the Sierra Nevada.

The deepest rock layer under the Mono–Inyo chain is made of the same granite and metamorphic rock as the Sierra Nevada. Above that are volcanic rocks, from basalt to rhyolite, that are between 3.5 million and 760,000 years old. Almost all the rock east of the Sierra Nevada in the Mono Basin area came from volcanoes.

Volcanoes erupted near what is now Long Valley from 3.6 to 2.3 million years ago. Then, rhyolite eruptions happened around Glass Mountain from 2.1 to 0.8 million years ago. The ash from the massive eruption of Long Valley Caldera about 760,000 years ago is still found in the thick Bishop Tuff rock layer that covers much of the region.

The first activity linked to the Mono–Inyo Craters system was eruptions of basalt and andesite lava 400,000 to 60,000 years ago. These eruptions filled the western part of the Long Valley Caldera with lava. Later, basalt and andesite eruptions moved to Mono Basin and lasted from 40,000 to 13,000 years ago.

Scientists believe there's a magma chamber (a large pool of molten rock) about 5.0 to 6.2 miles (8 to 10 km) below the Mono Craters. This magma chamber is separate from the one under Long Valley Caldera. The recent eruptions of the Mono Craters have been similar to those from Glass Mountain that happened before the Long Valley Caldera formed. Some scientists think that the Mono Craters' volcanism might be an early sign of a new caldera forming in the future.

Mammoth Mountain, a volcano made of overlapping lava domes, was formed by repeated eruptions of dacite and rhyodacite from 220,000 to 50,000 years ago. Dacite and rhyodacite also erupted in Mono Basin from 100,000 to 6,000 years ago.

Recent Eruptions

Many eruptions of silica-rich rhyolite from 40,000 to 600 years ago built the Mono Craters. Black Point, now on the north shore of Mono Lake, is a flat volcanic cone made of basaltic rock. It formed under a much deeper Mono Lake about 13,300 years ago, during the last Ice age. Several eruptions from 1,600 to 270 years ago formed Negit Island in Mono Lake. The magma feeding the Mono Lake Volcanic Field is separate from the Mono Craters magma.

Basaltic andesite lava built the Red Cones, two small cinder cones about 6.2 miles (10 km) southwest of Mammoth Lakes, around 8,500 years ago. The five Mammoth Mountain Craters are a group of explosion pits that run west-north-west for 1.6 miles (2.5 km) near the northern side of Mammoth Mountain.

The most recent eruption on the Mono Craters happened between the years 1325 and 1365. A vertical sheet of magma, called a dike, caused groundwater to explode into steam, creating a line of vents 4 miles (6 km) long. A mix of ash and crushed rock, called tephra, covered about 3,000 square miles (8,000 km2) of the Mono Lake region. This tephra was carried by the wind, forming a layer 8 inches (20 cm) deep 20 miles (32 km) from the vents and 2 inches (5 cm) deep 50 miles (80 km) away.

Hot clouds of gas, ash, and pulverized lava, called Pyroclastic flows, erupted from these vents. They spread out in narrow paths up to 5 miles (8 km) away, covering about 38 square miles (100 km2). Rhyolite lava then oozed out of the vents to form several steep-sided domes, including Panum Dome and the larger North Coulee flow. The youngest domes and coulees are 600 to 700 years old, making them some of the youngest mountains in North America.

Inyo Volcanic Chain and Paoha Island

The Inyo volcanic chain formed about 600 years ago, just a few years after the Mono Crater eruptions. This activity was also caused by a dike of similar molten rock. This dike eventually became 6.8 miles (11 km) long and up to 33 feet (10 m) wide. The ground above the dike cracked and faulted significantly.

Explosive eruptions happened from three separate vents in the summer of 1350 CE. Pieces of molten and solid rock were thrown out, small craters formed, and an eruption column rose high above the vents. Pumice and ash covered a large area downwind. About 1 inch (2.5 cm) of tephra was deposited where the town of Mammoth Lakes, California, now stands. A pyroclastic flow from the South Deadman vent traveled about 3.7 miles (6 km).

Some of the open pits were filled with thick, slow-moving lava, forming the South Deadman Creek, Glass Creek, and Obsidian Flow domes. Others, like the Inyo Crater Lakes near Deer Mountain, stayed open and later filled partly with water. Smaller explosion pits on the north side of Mammoth Mountain also formed at this time. In the past 6,000 years, about 0.19 cubic miles (0.8 km3) of magma has erupted from the Inyo part of the chain.

The last recorded volcanic activity in the chain was at Mono Lake between the years 1720 and 1850. Magma pushing up from below the lake caused the lakebed sediments to rise, forming Paoha Island. You can see exposed rhyolite on the north part of the island, and a group of seven dacite cinder cones and a lava flow on the northeastern corner. When geologist Israel Russell visited the island in the early 1880s, steam rose hundreds of feet high from Hot Spring Cove on the island, and the spring water was 150 °F (66 °C).

Human History

Using the Land

People have used the resources around the Mono–Inyo Craters for many centuries. The Mono Paiutes collected obsidian from the Mono–Inyo Craters to make sharp tools and arrowheads. They traded this obsidian with other Native American groups by carrying it over mountain passes in the Sierra Nevada. You can still find small pieces of Mono–Inyo obsidian at many old mountain campsites.

During the Gold rush in the 19th century, boomtowns (towns that grew very quickly) appeared near Mono Basin. The largest of these, Bodie (north of Mono Lake), was founded in the late 1870s. It grew so large that it needed a sawmill, which was located at Mono Mills, just northeast of the Mono Domes. The timberland east of the Mono Craters was cut down for wood.

As part of the California water wars, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power bought large areas of land in the 1930s in Mono Basin and Owens Valley to control water rights. Building an 11.5-mile (18.5 km) water tunnel under the southern part of the Mono Craters dome complex began in 1934 and finished in 1941. Workers faced challenges like loose gravel, pockets of carbon dioxide gas, and flooding. Water that used to flow into Mono Lake now passes through this tunnel on its way to the Los Angeles Aqueduct system.

Early Visitors' Thoughts

The chain of craters has been written about by several authors and naturalists. Mark Twain visited Mono Basin in the 1860s and wrote about Mono Lake, but he didn't mention the Mono–Inyo Craters, only the lake's two volcanic islands. In his book Roughing It (1872), he described the lake as being in a "lifeless, hideous desert..." and the "loneliest spot on earth..."

Naturalist John Muir explored the area in 1869. He called the "Mono Desert" a "... country of wonderful contrasts. Hot deserts bounded by snow-laden mountains,—cinders and ashes scattered on glacier-polished pavements,—frost and fire working together in the making of beauty. In the lake are several volcanic islands, which show that the waters were once mingled with fire." Muir described the Mono Craters as "... heaps of loose ashes that have never been blest by either rain or snow..."

In the early 1880s, geologist Israel Russell studied the area. His book Quaternary History of the Mono Valley (1889) was the first detailed scientific description of Mono Lake and its volcanic features.

Russell named the Mono Craters. He wrote: "The attention of every one who enters Mono Valley is at once attracted by the soft, pleasing colors of these craters as well as by the symmetry and beauty of their forms. They are exceptional features in the scenery of the region, and are rendered all the more striking by their proximity to the angular peaks and rugged outlines of the High Sierra."

Protecting the Area

The Mono Basin National Scenic Area, created in 1984, was the first National Scenic Area in the United States. It offers more protection than other United States Forest Service lands. It includes Mono Lake and its two volcanic islands, Black Point, Panum Crater, and much of the northern half of the Mono Craters. Groups like the Mono Lake Committee and the National Audubon Society have worked to slow down the diversion of water from streams that feed Mono Lake.

Volcanic Hazards

The Long Valley to Mono Lake region is one of three areas in California that the United States Geological Survey watches closely for volcanic hazards. These areas are monitored because they have been active in the last 2,000 years and could have explosive eruptions.

About 20 eruptions have happened along the Mono–Inyo Craters chain in the past 5,000 years, occurring every 250 to 700 years. Scientists believe these eruptions came from small, separate pockets of magma. The rate of eruptions has increased over the last 1,000 years, with at least 12 eruptions occurring.

All eruptions in the past 5,000 years from the Mono–Inyo Craters have been relatively small. Future eruptions will likely be similar in size. There is about a 0.5% chance (one in 200) each year that an eruption will happen along the chain. An eruption along the Mono–Inyo chain is probably more likely in the near future than an eruption inside the Long Valley Caldera.

What Could Happen?

Future eruptions along the Mono–Inyo Craters could have various effects. Ash and rock fragments (tephra) might pile up to 33 feet (10 m) thick near an erupting vent. Downwind, tephra could be more than 7.9 inches (20 cm) deep at 22 miles (35 km) away, and 2.0 inches (5 cm) deep at 53 miles (85 km) away. Winds in the area usually blow towards the east or northeast. Volcanic ash would likely affect air travel routes east of the eruption.

Very hot flows of gas, ash, and pulverized rock (pyroclastic flows and surges) could cause severe damage up to 9.3 miles (15 km) from an explosive eruption. The amount of damage depends on where the vent is, the landscape, and how much magma erupts. Pyroclastic flows from vents on Mammoth Mountain or other high places could travel farther because they gain speed going downhill. Valleys would be more affected than ridges, but flows could still go over some ridges. Eruptions near snow could create lahars (mud and ash flows) that would damage valleys and waterways. Steam explosions under a lake could create large waves that flood nearby areas and start mudflows.

Basalt lava flows might extend more than 31 miles (50 km) from their vent. However, dacite and rhyolite lavas produce short, thick flows that rarely go more than 3.1 miles (5 km) from their vent. These flows often form mound-shaped features called lava domes. Rock fragments thrown from a growing lava dome could reach 3.1 to 6.2 miles (5 to 10 km) away. If a steep-sided growing dome partly collapses, it can send pyroclastic flows outward at least 3.1 miles (5 km). Taller domes tend to create larger pyroclastic flows that travel farther.

Things to Do

There are many fun activities to do along the Mono–Inyo Craters chain. The Mono Basin National Scenic Area visitor center is located near Mono Lake, just off U.S. Route 395. Here, you can find a bookstore, information from USDA Forest Service Rangers, and museum exhibits to help you learn about the area. The Mono Lake Committee also has an office and visitor center in Lee Vining. You can get information on camping, hiking, and tours at either location.

Several paved roads surround the Mono–Inyo Craters. U.S. 395 is a scenic route that generally runs alongside the volcanic chain. California State Route 120 leads to the northern and eastern parts of the Mono Domes, including Panum Crater. The Mammoth Scenic Loop takes you close to the Inyo Craters. To get direct access to the Mono–Inyo Craters, you'll need to drive on unpaved roads and then walk.

The town of Mammoth Lakes, located near the southern end of the chain and Mammoth Mountain, is the largest town nearby. The Mammoth Mountain Ski Area is close by, and you can take gondola rides year-round (if the weather is good) to the mountain's top. From the summit of Mammoth Mountain, you get amazing views of the craters and domes of the Mono–Inyo volcanic chain, Mono Lake, the Sierra Nevada, and the Long Valley Caldera.

Mono Lake itself offers many activities, including walking tours among its unique tufa towers (rock formations), boat tours of the lake, and great opportunities for birdwatching. The lake is too salty for fish, but you can fish in the streams that flow into Mono Lake. Other activities include hiking around and on the craters and domes, and mountain biking outside of the Scenic Area boundaries.

See also

In Spanish: Cráteres Mono-Inyo para niños

In Spanish: Cráteres Mono-Inyo para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |