Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee facts for kids

The Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee was a group formed in 1943. They protested against the draft of Nisei (American citizens whose parents were Japanese immigrants). These young men were living in Japanese American concentration camps during World War II.

Kiyoshi Okamoto started a "Fair Play Committee of One" in 1943. This was his response to a tricky "loyalty questionnaire" from the War Relocation Authority. Later, Frank Emi and other people held in the Heart Mountain camp joined him. The committee got its name from this camp.

The group had seven main leaders. More people joined as draft notices arrived in the camp. They refused to join the army or volunteer for the draft. They wanted their rights as citizens restored first. By June 1944, many young men were arrested. They were accused by the U.S. government of breaking draft laws.

The Poston camp in Arizona had the most draft resisters. But the Fair Play Committee was the most well-known group protesting the draft. Heart Mountain had the highest rate of draft resistance compared to its population. Nearly 300 young men from all ten camps eventually resisted the draft.

A total of 85 Heart Mountain resisters and the committee leaders were found guilty. They were sentenced to three to five years in federal prison. In 1947, President Harry S. Truman pardoned them. However, for many years, the Fair Play Committee members were seen as traitors by some in the Japanese American community. This was especially true when compared to the brave 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd RCT. These military units were famous for their courage.

After the war, Japanese Americans worked hard to rebuild their lives. In the 1970s, a movement began to get justice for their forced imprisonment. As former camp residents shared their stories, feelings about the resisters started to change.

Since the late 1900s, these draft resisters have been recognized. They are seen as people who followed their conscience. They hold an important place in the history of the Japanese American incarceration. In 2002, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) formally apologized. During the war, the JACL had opposed the committee. They even worked with the FBI to prosecute its members.

Contents

Why the Committee Formed

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the United States entered World War II. Japanese Americans were quickly seen as enemies. This was partly due to existing unfair feelings and business rivalries. Especially on the West Coast, where many Japanese Americans lived, leaders pushed for a "solution."

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. This order allowed military leaders to remove people from certain areas. Over the next few months, about 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese Americans were forced from their homes. They were sent to inland concentration camps. Two-thirds of them were American citizens, born in the United States.

Heart Mountain was one of ten camps. It was located in Wyoming. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) ran these camps. The WRA made Japanese Americans build their own prison barracks. By early 1943, Heart Mountain had over 10,700 people.

The WRA then started giving out a "leave clearance registration form." They hoped some Japanese Americans would move outside the West Coast. This would help reduce overcrowding in the camps. At first, only Nisei who volunteered to move got the form.

However, the U.S. needed more soldiers for Europe and North Africa. WRA officials saw a chance to check the loyalty of Japanese Americans in the camps. They expanded the "loyalty questionnaire" to find potential soldiers and "troublemakers."

The Loyalty Questionnaire

The loyalty questionnaire was very unpopular in all the camps. This was mainly because of its last two questions:

- Would the person volunteer for military service (Question 27)?

- Would the person give up loyalty to the Emperor of Japan (Question 28)?

Many young men felt insulted. They were asked to join the army for a country that had imprisoned them. They had lost their family businesses and homes. They also disliked the second question. It seemed to assume Japanese Americans were loyal to Japan, not the U.S. Others were simply confused. They worried that saying "yes" to Question 27 meant volunteering for dangerous combat. They also feared that giving up loyalty to Japan would be seen as admitting guilt. This could lead to deportation.

Starting the Fair Play Committee

The Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee began because of the loyalty questionnaire. Frank Emi refused to answer the questions. He wrote that he could not complete the form "under the present circumstances." He put up flyers around the camp telling others to do the same.

Kiyoshi Okamoto was already a known figure in Heart Mountain. He had helped organize a "Congress of American Citizens." This group protested the lack of information from the WRA and military. Okamoto continued to protest the loyalty questionnaire. He also spoke out against the unfair treatment of Nisei citizens. In November 1943, he called himself a "Fair Play Committee of One."

Later that year, Emi and others met with Okamoto. They started holding informal meetings. They discussed their complaints against the WRA. They also talked about what they could do.

The meetings stayed small until early 1944. That's when Nisei men, who had been excused from the draft, were added back to the draft pool. They started getting induction notices in the camp. The Fair Play Committee formally elected its seven founders as leaders on January 26. These founders were Okamoto, Emi, Sam Horino, Guntaro Kubota, Paul Nakadate, Min Tamesa, and Ben Wakaye.

Their first public meeting was on February 8, 1944. Sixty young men came to hear the leaders' arguments. They spoke against forcing citizens to join the army when their rights had been taken away. As more Heart Mountain men were drafted, interest in the Fair Play Committee grew. A rally on March 1 attracted over 400 people. Public meetings continued. The Committee became a formal group. Members paid a $2 fee. They also had to be loyal U.S. citizens. They had to be willing to serve if their rights were restored.

Draft Resistance and Legal Action

The Fair Play Committee began meeting regularly in February 1944. They held evening meetings in the camp's mess halls. Many young men attended. They wondered whether to report for their required physical exams. At first, Okamoto, Emi, and other FPC leaders avoided telling people directly to disobey the draft. They feared punishment from military or WRA officials.

On March 4, 1944, the Committee changed its approach. They announced their plan to "refuse to go to the physical examination or to the induction." They wanted to challenge the issue in court. On March 6, the first two resisters refused their physicals. By the end of the week, ten more joined them.

Many Japanese Americans, both inside and outside the camp, criticized the committee. The camp newspaper, the Heart Mountain Sentinel, published articles against the Fair Play Committee. As more people joined the FPC meetings, Sentinel articles called members "deluded youths." The national newspaper of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the Pacific Citizen, also wrote against the resisters.

After almost a month, U.S. Marshals entered the camp on March 25, 1944. They arrested the first twelve draft resisters. While these resisters waited for their court hearings, Frank Emi and two other Fair Play leaders tried to walk out of Heart Mountain. They knew they would be stopped. This was a protest against being held as prisoners. Camp officials transferred Kiyoshi Okamoto to another camp. Still, the number of young men disobeying draft orders grew. By June, there were sixty-three.

During this time, Okamoto wrote to Roger N. Baldwin, head of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). He asked for legal help to challenge the draft of people held in camps. Baldwin replied in a letter. He said the men were "within their rights" but "had no legal case at all." He refused to have the ACLU represent them. Records later showed that the JACL and ACLU worked together. They wanted to stop the draft resisters' appeals.

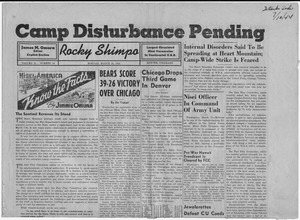

The Pacific Citizen newspaper also published an editorial on April 8, 1944. It called the resisters "draft dodgers." It said they had "injured the cause of loyal Japanese Americans everywhere." Ben Kuroki, a Japanese American war hero, visited Heart Mountain. He said the resisters were "Fascists." However, James Omura of the Denver-based Rocky Shimpo newspaper wrote articles supporting the FPC. He argued that Nisei rights should be restored before they were drafted.

Trials and Sentences

In the largest federal trial in Wyoming history, sixty-three arrested resisters were found guilty. They were accused of breaking draft laws and working against the government. Judge Thomas Blake Kennedy sentenced them to three years in federal prison. On July 1, 1944, the Heart Mountain Sentinel wrote that the actions of the 63 defendants were "as serious an attack on the integrity of all nisei as the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor." Twenty-two more young men were tried later and received the same sentence. This brought the total number of Heart Mountain draft resisters to eighty-five.

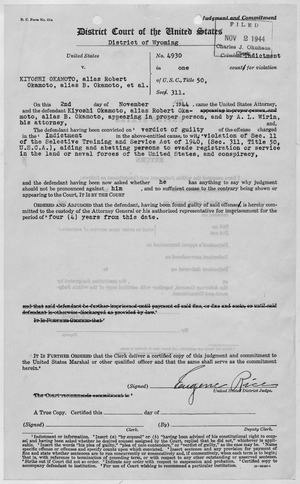

On May 10, 1944, the seven leaders of the Fair Play Committee and James Omura were accused of a crime. They were charged with planning to help others break the draft laws. (Omura and the FPC leaders were older. They were not subject to the draft themselves. The government used the "conspiracy" charge to prosecute them.) Their case was heard in October 1944. Omura was found not guilty. The seven Fair Play leaders were found guilty. They were sentenced to two to four years in federal prison.

After World War II

In 1945, a court overturned the convictions of the seven Fair Play Committee leaders. The court found that the jury in their trial had been told not to consider their reasons for protesting. The eighty-five younger Fair Play members stayed in prison. Many were released early for good behavior in July 1946. The rest of the Heart Mountain resisters, and over 200 from other camps, were not released until December 1947. President Harry Truman gave them a full pardon.

The West Coast was reopened to Japanese American settlement on January 2, 1945. Over the next few months, the camps slowly emptied. People either returned home or moved to cities like Chicago and New York. Those who returned early faced severe housing and job shortages. There was still a lot of unfair treatment. The Fair Play members faced a tough job market and discrimination. They also faced hostility from other Japanese Americans.

The brave actions of the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regiment were widely publicized. These Nisei soldiers were seen as heroes. They helped create a positive image of patriotic Japanese Americans. Many believed they helped end the incarceration. The draft resisters, however, were seen by many as working against this goal. They were thought to have created more difficulties for Japanese Americans. In February 1946, the JACL officially condemned the Fair Play Committee. They held this position for over fifty years.

Despite tensions, former FPC members rebuilt their lives. Most did not talk about their wartime resistance. Public opinion remained mostly against the Committee until the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, activists began to reexamine the reasons for their resistance. This movement led to the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. This law gave a formal apology and money to camp survivors. Interest in the Fair Play resisters grew in the following decades. By the 1990s, many Nisei veterans groups began to see the resisters differently. They saw them as showing a different kind of courage and patriotism.

Around this time, the JACL started to try and make peace with the resisters. In 1994, Frank Emi and Mits Koshiyama (another Fair Play member) were invited to speak at the JACL's national meeting. Five years later, a proposal to apologize to draft resisters was introduced. It was quickly stopped by opposing members. A successful proposal finally passed a vote at the JACL's 2000 convention. In May 2002, the JACL held a public ceremony. They apologized to the Fair Play Committee and other wartime resisters.

The last surviving member of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, Frank Emi, passed away on December 1, 2010.

Creative Works About the Committee

- John Okada's novel, No-No Boy (1956), is set after the war. It is about a main character who was imprisoned for refusing the draft.

- Frank Abe, Conscience and the Constitution, PBS, 2000

- Allegiance (2013), a musical that first showed in San Diego, California.

See also

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |