Rancho Petaluma Adobe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rancho Petaluma Adobe |

|

|---|---|

Rancho Petaluma Adobe, California

|

|

| General information | |

| Town or city | east of Petaluma, California |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 38°15′20″N 122°35′04″W / 38.25547°N 122.58451°W |

| Construction started | 1834 |

| Completed | 1857 |

| Cost | $80,000 |

| Client | Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | adobe brick and timber |

| Size | 200 x 145 feet (44.2 m) |

|

Petaluma Adobe

|

|

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Casa Grande Road, Petaluma, California |

| Area | 5 acres (2.0 ha) |

| Built | 1836 |

| Architectural style | Adobe/Monterey Colonial |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000151 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 15, 1970 |

| Designated NHL | April 15, 1970 |

Rancho Petaluma Adobe is a very old ranch house in Sonoma County, California. It was built from special adobe bricks starting in 1836. A man named Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo ordered its construction. This building was the biggest private adobe structure ever built in California. It is also the best example of the Monterey Colonial style of architecture in the United States.

Today, part of the old ranch is saved as the Petaluma Adobe State Historic Park. It is recognized as both a California Historic Landmark and a National Historic Landmark. You can find the park on Adobe Road, just east of the town of Petaluma, California.

Contents

What the Rancho Petaluma Adobe Looks Like

The Adobe was built to do two important jobs. First, it was the main office for a busy ranch. Second, it was a strong fort to protect against attacks. These attacks might have come from the Russians living nearby or from local Native American tribes.

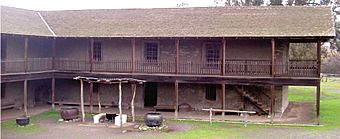

The building originally had two parts, each with two stories. These parts wrapped around an open yard that was about 200 by 145 feet. Workers built it using adobe bricks and strong redwood timbers. The floors were made of planks, and the roof was gently sloped and covered with shingles.

A wide, covered porch on the second floor protected the adobe walls from bad weather. It also offered good spots to shoot from if there was an attack. Large gates stood between the buildings on the north and south sides of the main courtyard.

Inside the Adobe Building

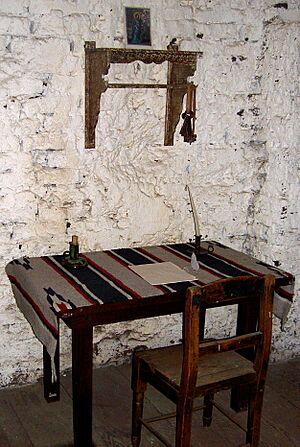

The southwest part of the building was where the Vallejo family stayed when they visited. Some of these walls were smooth and painted white. The kitchen and dining room were on the ground floor. The dining room even had special imported glass windows!

Upstairs, on the second floor, were the family's bedrooms. There was also Vallejo's office and rooms for guests. The ranch manager had his own sleeping room. The most important workers also had shared sleeping areas here. The dining room downstairs and the family's and manager's rooms had fireplaces to keep warm.

The eastern part of the building was never fully finished. Workers built the walls, but they never added floors or a roof. This part of the building is gone now. So, what you see of the Petaluma Adobe today is only about half of its original size.

History of the Rancho Petaluma Adobe

The Mexican-American Era and Building the Ranch

In 1834, the Governor of California, José Figueroa, told Lieutenant Vallejo to move his soldiers north. Vallejo was given the first lands of Rancho Petaluma. In 1836, Vallejo started building the ranch house. He spent a lot of money and effort, about $80,000, on the project. However, the building was never fully completed as planned.

Vallejo's younger brother, Salvador Vallejo, oversaw most of the construction. Between 1836 and 1839, many Native Americans worked at the ranch. At least 2,000 people helped make bricks, carry wood, build structures, cook, and farm. They also made tools, tanned animal hides, and cared for the large herds of cattle.

The Vallejo family sometimes used the Petaluma Adobe as a summer home. They also hosted guests there. Their main home was in the nearby town of Sonoma. Vallejo's Sonoma home, called Lachryma Montis, is now part of Sonoma State Historic Park.

Vallejo had a manager, called a mayordomo, named Miguel Alvarado. Alvarado lived at the ranch and handled the daily tasks. From 1836 to 1857, up to 2,000 Native Americans worked at Rancho Petaluma. This ranch became one of the biggest north of the San Francisco Bay. It was a very important place for business and social life in Northern California.

Life and Work at the Ranch

The ranch had many workshops, including a tannery for making leather and a smithy for metalwork. It also had a grist mill powered by Adobe Creek to grind grain. The ranch owned over 12,000 cattle. About a quarter of them were used each year.

The main products from the cattle were hides (animal skins) and tallow (animal fat). These were sent by river boats on the Petaluma River to the San Francisco Bay. Hides and tallow were the ranch's main source of money. Much of the meat, however, was not used. Vallejo earned a lot of money each year from selling hides and tallow.

The ranch also had up to 3,000 sheep, mainly for their wool. Native American artisans in the ranch shops made many items. These included candles, soap, thousands of wool blankets, and boots and shoes for soldiers. They also made saddles.

In 1843, Mexican Governor Manuel Micheltorena gave Vallejo more land. This was the 84,000-acre Rancho Suscol. This new land stretched the Rancho Petaluma south to the San Francisco Bay. It also went southeast past the city of Vallejo. However, in 1862, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that Vallejo did not own the Rancho Suscol land.

Native American Workers at the Ranch

Having many workers who did not cost much was key to the ranch's success. Native American workers usually received food, clothing, and other goods as payment.

The most skilled workers were Native Americans who had been trained at missions. Vallejo was good at getting these workers from the missions at Sonoma and San Rafael. They had the skills needed to run the ranch and its workshops. These workers made up most of the year-round staff. The most important workers lived in rooms on the second floor of the Adobe. Other year-round workers lived in reed huts in a historic Native American village along Adobe Creek.

Other Native Americans, whom the Californios called "gentiles," worked seasonally. They helped with the grain harvest, the cattle slaughter, or making adobe bricks. Some of these individuals or families chose to work at the Rancho for a time. Others might have been sent by Vallejo's friends, like Chief Marin or Chief Solano. Some Native Americans at Rancho Petaluma were not working there by choice. They might have been captured by soldiers as punishment for stealing or raids.

The Ranch's Decline (1846–1910)

The ranch's fortunes changed between 1846 and 1848 when the United States and Mexico went to war. Lieutenant Colonel Vallejo was put in prison because of his role in the Mexican military. While he was away, John C. Frémont took the ranch's horses, cattle, and grain for his soldiers. Many Native American workers, who were the main workforce, ran away from the soldiers. After this, the ranch became less valuable and less profitable each year.

In 1851, Vallejo asked the United States for money for the animals and supplies that Fremont had taken. A group of officers looked at his claim. They reduced the amount, and Vallejo was paid $48,700 in 1855.

The University of California thought about buying the ranch for a new campus in 1856. Around 1857, Vallejo sold the building and 1,600 acres to William Whiteside for $25,000. Whiteside then sold it to William Bliss. The southeast half of the adobe fell apart, and the Bliss family could not afford all the repairs needed.

Becoming a Historic Park

In 1910, a group called the Native Sons of the Golden West bought what was left of General Mariano G. Vallejo's large adobe ranch house. More than half of the building had been ruined by neglect and nature. In 1932, it was named California State Historical Landmark #18.

After many years of hard work and raising money, the fully restored historic site was given to the State of California in 1951. In 1970, it was recognized as a National Historic Landmark.

Today, it is the main attraction of Petaluma Adobe State Historic Park. About 80% of the adobe bricks are original, but most of the wood has been replaced. You can still see part of the foundation of the half that fell apart. There is also a small museum and other displays to explore.

Locals often call it "Old Adobe."

See also

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |