Fort Union National Monument facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fort Union National Monument |

|

|---|---|

Fort Union Ruins

|

|

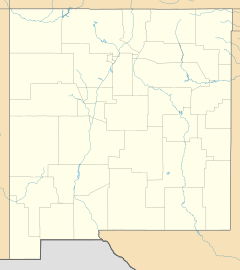

| Location | Mora County, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Watrous, New Mexico |

| Area | 720.6 acres (291.6 ha) |

| Established | June 28, 1954 |

| Visitors | 9,570 (in 2023) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Fort Union National Monument |

|

Fort Union National Monument

|

|

| Built | 1851 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000044 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

Fort Union National Monument is a special place in Mora County, New Mexico. It's managed by the National Park Service. This monument protects the old remains of three forts. These forts were built a long time ago, starting in the 1850s.

When you visit, you can also see old wagon ruts. These ruts were made by wagons traveling on the famous Santa Fe Trail. The trail had two main paths, the Mountain and Cimarron Branches, and you can see their marks here.

The monument has a visitor center. Inside, you'll find a museum with cool historical items. There's also a film that tells the story of the fort. You can walk a special trail that guides you through the ruins of the second and third forts. You can even spot the remains of the first fort across the valley!

Fort Union National Monument is open most days from 8:00 am to 4:00 pm. It's closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas Day, and New Year’s Day. The best part? It's free to visit!

Contents

Exploring Fort Union's Past

Imagine stepping back in time to 1857! A traveler named William Davis visited Fort Union then. He said it looked more like a quiet village than a military base. The fort had wide, straight streets. Its buildings were made from pine logs from nearby mountains. Everything looked neat and cozy for the soldiers and officers living there.

Why Fort Union Was Built

After the U.S.-Mexican War ended, the United States gained a lot of new land. This included parts of what are now California, New Mexico, and other states. The U.S. Army needed to protect the people and trade routes in these new areas.

At first, soldiers were stationed in towns. But this didn't work very well. Soldiers often got distracted in busy civilian communities. So, in 1851, Lt. Col. Edwin V. Sumner decided to move the army's main base. He chose a spot where two branches of the Santa Fe Trail met. This new spot became Fort Union.

The First Fort: A Busy Hub

The first Fort Union was started in August 1851. For ten years, it was a very important place. It served as a base for military operations. It was also a key stop on the Santa Fe Trail. Travelers could rest there and buy supplies at the sutler's store. This store sold things the army didn't provide. Fort Union quickly became the main military supply center in the Southwest.

During the 1850s, soldiers called "dragoons" (mounted riflemen) worked to keep the Santa Fe Trail safe. They protected travelers from raids by some Native American tribes. For example, in 1854, they had a big campaign against the Jicarilla Apaches. They also worked to protect the plains from other tribes like the Utes, Kiowas, and Comanches.

Fort Union During the Civil War

The American Civil War began in 1861. Many regular soldiers from Fort Union were sent to fight in the East. Volunteer soldiers took their place.

People worried that Confederate forces might invade New Mexico. So, a second Fort Union was built. This fort was shaped like a star and made of earth. It was designed to defend against an invasion coming from Texas.

In 1862, soldiers from Fort Union, along with volunteers from Colorado and New Mexico, stopped the Confederates. They fought at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, near Santa Fe. The Confederates lost and went back to Texas. This battle was very important. It ended the Civil War in the Southwest. It also kept valuable mines in Colorado from falling into Confederate hands. The second Fort Union was then no longer needed.

The Third Fort: A Giant Supply Center

Work on the third Fort Union began in 1863. New Mexico was now safely under federal control. This new fort was huge and took six years to finish. It had a military post and a separate supply depot. This depot had warehouses, corrals, shops, offices, and homes for workers.

The supply depot was actually more important than the military post. It employed many more people, mostly civilians. An ordnance depot, where weapons and ammunition were stored, was also built nearby.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, soldiers from Fort Union continued to be involved in operations against various Native American tribes. By 1875, peace finally came to the Southern Plains. After this, Fort Union's soldiers sometimes helped track down outlaws or settle disputes.

The supply depot kept running strong until 1879. That's when the Santa Fe Railroad arrived. Trains became the main way to transport goods, replacing the old Santa Fe Trail. By 1891, Fort Union was no longer needed and was closed down.

Famous Faces at Fort Union

Fort Union was home to some important military units. It was the headquarters for the 8th Cavalry in the early 1870s. Later, it was the headquarters for the 9th Cavalry in the late 1870s.

A very famous person, Kit Carson (whose full name was Christopher Carson), was the commander of Fort Union for a few months. He led the fort from December 1865 to April 1866.

Images for kids

See also

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |