The Bowl (Cherokee chief) facts for kids

The Bowl (also known as Chief Bowls), whose Cherokee name was Di'wali, was an important Cherokee leader. He was born around 1756 and died on July 16, 1839. Di'wali led the Chickamauga Cherokee during the Cherokee–American wars. He also served as a Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation–West. Later, he became a key leader of the Texas Cherokees, also called Tshalagiyi nvdagi.

Contents

Early Life of Di'wali

Di'wali was born in a Cherokee town called Little Hiwassee around 1756. This town was in what is now North Carolina. His mother was Cherokee, and his father was a Scottish trader. An early Cherokee historian, Emmet Starr, said that Di'wali looked very Scottish. He had light eyes, red hair, and some freckles.

A Young Warrior's Path

As a young man, Di'wali followed Dragging Canoe. Dragging Canoe helped start the Chickamauga Cherokee group. This group supported the British during the American Revolutionary War. Di'wali fought alongside Dragging Canoe and John Watts in the Cherokee–American wars. During this time, Di'wali became the chief of Running Water Town. This town is near what is now Whiteside, Tennessee. After American forces destroyed the Chickamauga settlements in 1794, Di'wali went back to Little Hiwassee.

Moving West for New Homes

To find better hunting grounds and avoid white settlers, Di'wali led many Cherokee people west. In 1809, they crossed the Mississippi River. They settled in the Louisiana Territory along the St. Francis River. This area is near what is now New Madrid, Missouri.

The next year, more Cherokee people arrived. They formed a tribal government. Di'wali was chosen as the first Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation–West. In 1812-1813, Di'wali moved his people south. They settled near what is now Conway, Arkansas. In 1813, Degadoga became the new Principal Chief.

White settlers kept moving into the Arkansas Territory. So, in the winter of 1819-1820, Di'wali led about 60 Cherokee families into Spanish Texas. They lived for two years along the Red River in northeast Texas. The community chose Di'wali as their Head Chief, or ugu'.

As more white settlers came to the Red River area, Di'wali moved his community again. This time, they went to the Trinity River valley, near present-day Dallas. The next year, they moved again. They settled about fifty miles north of what is now Nacogdoches, Texas. At this time, Richard Fields became the leader of the "Cherokee and their associated bands."

Working for Land Rights

On November 8, 1822, Richard Fields and Di'wali made an agreement. They met with José Félix Trespalacios, the governor of the Province of Tejas. The agreement said the Cherokee could peacefully live on lands in east Texas. Fields and Di'wali then traveled to Mexico City. They asked the Mexican government for a treaty. They wanted to settle there permanently.

The Mexican government would not give up ownership of the land. They only allowed the Cherokee to live there and farm.

It was hard to make the 1822 agreement work. On April 15, 1825, a white immigrant named Benjamin Edwards received land from Mexico. This land was in areas the Cherokee claimed in east Texas. Many white settlers in nearby Nacogdoches were also unhappy with the Mexican government. They rebelled in what was called the Fredonian Rebellion.

Richard Fields, as the war chief, and John Dunn Hunter, as the peace chief, talked with the Fredonian leaders. But Di'wali told the Cherokee not to help the rebels. He believed that if they stayed loyal to Mexico, their land claims would finally be recognized. Di'wali convinced his people. The Cherokee stayed loyal to Mexico during the rebellion.

Because they supported the rebellion, Fields and Hunter were executed by the Mexican government on May 8, 1827. Di'wali then became the war chief.

Seeking a Secure Homeland

After the Fredonian Rebellion, Stephen F. Austin and other Mexican officials praised Di'wali and the Cherokee. Di'wali was called to Nacogdoches. On July 19, 1827, he was made a lieutenant-colonel in the Mexican Army. Di'wali kept trying to get a written promise from Mexico for the Cherokee lands. But the Mexican government never gave a written agreement. By 1830, about 800 Cherokee lived in up to seven settlements in Texas. They became known as the Texas Cherokee, or Tsalagiyi nvdagi.

When the Texas Revolution began, the Texas Cherokee decided to stay neutral. But Sam Houston, who had married into the Cherokee tribe, wanted an alliance. Houston had a long friendship with Chief Di'wali. He wanted to give the Cherokee what Mexico had refused. Houston was given power by the new Texas government. He negotiated a treaty with the Cherokee and other groups. This treaty granted them over 2.5 million acres of land in east Texas.

The treaty said that the Cherokee and their twelve associated tribes had a right to these lands. These lands were north of the San Antonio road and the Neches River. They were also west of the Angeline and Sabine rivers. The new Texas government promised to set up clear boundaries and guarantee their peaceful enjoyment of the land.

The Cherokee agreed, hoping to finally have a secure homeland. Di'wali signed the treaty for the Texas Cherokees on February 23, 1835. This happened near what is now Alto, Texas. Because of this, the Texas Cherokee supported the Texans against Santa Anna.

On December 20, 1836, Sam Houston, as President of the Republic of Texas, asked the Texas Senate to approve the treaty. He said it was fair and the best possible. However, the Senate of the Republic of Texas refused to approve it. They said the Cherokee had not actively fought with Texans. They also said the treaty conflicted with a land grant given to David G. Burnet. Despite Houston's objections, the Senate officially canceled the treaty on December 16, 1837. Soon after, land was sold within the Cherokee lands.

Even though relations were difficult, Houston and Di'wali remained close friends. Di'wali helped Houston by representing Texas in talks with the Comanche tribe. Di'wali still wanted to secure land for his people. He looked to Mexico again when Vicente Córdova tried to rebel against the Republic of Texas. The Mexican government offered the Cherokee land if they supported this rebellion. Di'wali allowed Córdova's militia to operate in Cherokee lands in 1838.

In May 1839, a member of Córdova's militia was killed. Texas officials found documents that suggested the Texas Cherokee were working with pro-Mexican forces. The Córdova Rebellion had been stopped quickly in August 1838. But these new documents led the new President of the Republic of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar, to accuse Di'wali of secretly helping Córdova.

Conflict with the Texas Republic

In 1839, President Lamar said that the Cherokee and Comanche tribes should be driven from Texas. He believed that getting rid of the Native American tribes was necessary to open up land for white settlers. Lamar ordered the Texas military to build a fort on the Great Sabine. This was in the southwest corner of what is now Smith County, Texas. Di'wali warned that this would cause a fight.

Lamar sent a message that the Cherokee must leave or be forced out. But Di'wali insisted that Texas should honor the 1836 treaty. John Henninger Reagan, a representative for Lamar, met with Di'wali in early July. Reagan delivered Lamar's demands and gave Di'wali a few days to talk with his Council.

Reagan later wrote about his second meeting with Di'wali. He said Chief Bowles looked very serious. Di'wali told him that his young men and all the council members, except himself and White Chief Big Mush, wanted war. His young men thought they could defeat the white settlers. But Di'wali knew the white settlers would eventually win, though it would cause ten years of bloody war. He asked if they could wait until his people harvested their crops. Reagan said he had no power to change the President's demand. Di'wali understood this meant war would happen. He said he had led his people for a long time. He felt it was his duty to stand by them, no matter what happened to him.

The Final Fight

On July 14, Lamar sent troops led by General Thomas Rusk to take over the Native American territory. The Cherokee fled their town and moved north into what is now Van Zandt County, Texas. On July 15, they stopped and prepared to defend themselves at the Neches River.

On the morning of July 16, Di'wali faced his pursuers. Even though his forces were much smaller, he encouraged his people to fight bravely. He was heard urging them to charge many times during the battle. But eventually, his troops ran out of ammunition. Di'wali ordered a retreat, but he stayed behind.

He sat on his horse, wearing a military hat and a sword given to him by Sam Houston. Di'wali faced the Texans as they advanced. The Texan forces shot his horse. Then they shot the chief in the thigh and the back. Di'wali could not walk, but he sat up on the ground. He was singing a war song when Captain Robert W. Smith came up to him. Smith then shot Di'wali in the head. Smith took the sword from Di'wali's body and cut off pieces of skin from his arm as souvenirs.

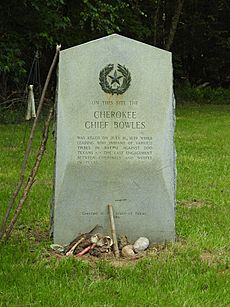

John H. Reagan remembered Di'wali as a dignified and manly leader. He admired Di'wali's loyalty to his tribe, even when their decision for war went against his own judgment. He also respected Di'wali's courage in battle. As he had asked, Di'wali's body was left on the battlefield, following tradition. A historical marker now stands where Chief Di'wali died. In 1995, a funeral for Di'wali was held by his descendants. This was on the 156th anniversary of his death.

Images for kids