Comanche–Mexico Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Comanche–Mexican Wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Comanche Wars | |||||||

The Comanche were famous for their horsemanship. By George Catlin, 1835. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Comanche Kiowa Kiowa Apache |

|||||||

The Comanche–Mexico Wars were a series of conflicts that took place from 1821 to about 1870. These wars were part of the larger Comanche Wars. The Comanche people, along with their allies the Kiowa and Kiowa Apache, launched huge raids deep into Mexico. They killed thousands of people and stole hundreds of thousands of cattle and horses.

These raids started because Mexico's military became weaker after it gained independence in 1821. Also, there was a big demand in the United States for stolen Mexican horses and cattle. The biggest Comanche raids happened from 1840 to the mid-1850s. When the U.S. Army invaded northern Mexico in 1846 during the Mexican–American War, the area was already in ruins. The Comanche were finally defeated by the U.S. Army in 1875 and moved to a reservation.

Contents

Understanding the Comanche Wars

Who were the Comanche?

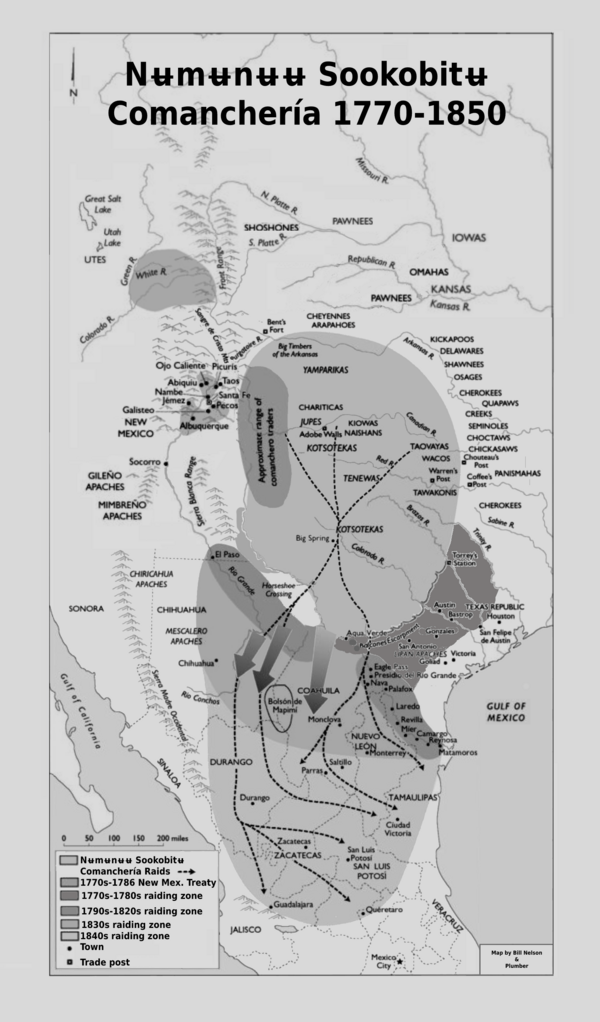

The Comanche were a very powerful Native American group. U.S. Army General James Wilkinson once called them "the most powerful nation of savages on this continent." This power was clear as the United States and the new country of Mexico fought over land. The Comanche saw themselves as owners of a large area of land. This land was about 500 by 400 miles wide. It stretched from the Arkansas River in Colorado to near the Rio Grande in Texas.

In the early 1800s, over 10,000 Comanches lived in this land. They called it Comancheria. About 2,000 Kiowa and Plains Apache also lived there. Sometimes, the Comanche let other tribes, like the Wichita, hunt on their land.

How did the Wars Begin?

The Comanche first met the Spanish in New Mexico in 1706. There were some fights, but peace treaties were made in 1785 and 1786. The Spanish liked the Comanche as allies against the Apache. They traded goods and corn for horses, captives, and buffalo meat. They also gave the Comanche gifts.

This good relationship changed in 1821 when Mexico became independent from Spain. The new Mexican government did not have money to keep giving gifts to the Comanche. They were also busy with their own political problems.

In the 1820s and 1830s, the Comanche faced many challenges. Other tribes, like the Osage, were strong enemies. Also, the U.S. government forced many Eastern Indian tribes, like the Five Civilized Tribes, Shawnee, and Delaware, to move west. This brought them into conflict with the Comanche. The Comanche lost some battles to these tribes, who often had better weapons.

Anglo-Americans (people of European descent from the U.S.) also started moving into the area. Traders used the Santa Fe Trail, which crossed Comanche land. Hunters reduced the buffalo herds. Northern Plains Indians like the Cheyenne and Arapaho moved south. They were also strong fighters. European diseases also caused Comanche numbers to drop.

The Comanche tried to make peace with Mexico. They asked Mexico for military help against other tribes, but Mexico refused. This made the Comanche less committed to peace with Mexico. However, Mexican leaders tried to improve trade with the Comanche in the early 1830s.

Why did the Comanche raid Mexico?

A big reason for the raids was the high demand for horses and mules in the United States. The Comanche could get these animals by raising them, catching wild horses, or stealing them from Mexican ranches. Stealing was often the easiest way for young Comanche men to get rich. A young man could improve his life by raiding for horses and captives. The wealth he gained could help him buy a wife.

The Mexican government believed the U.S. and independent Texas encouraged these raids. They thought Americans traded guns to the Comanche for stolen horses. In 1826, a Mexican official asked the U.S. to stop "traders in blood." In 1835, the state of Chihuahua offered money for each scalp of a hostile Indian. This led to some scalp hunters, including Americans and other Native Americans, killing Apache and peaceful Indians. But it did not seem to stop the Comanche much.

Comanche Diplomacy and Strategy

Making Peace with Neighbors

The Comanche were very smart in how they dealt with their neighbors in the 1830s. They had a flexible plan. With New Mexico, a Mexican area to their west, they had good trading relationships. New Mexico was helpful to the Comanche, and its people avoided war with them. In 1841, the Mexican government told New Mexico's Governor Manuel Armijo to fight the Comanche. But Armijo refused, saying war would "bring complete ruin to the Department of New Mexico."

With their western side safe, the Comanche focused on their northern and eastern borders. In 1835, they met with U.S. soldiers and Eastern Indians in the Wichita Mountains of Oklahoma. They made a peace agreement. This agreement allowed Eastern Indians and Anglo-Americans to hunt on Comanche lands. But it did not stop the Comanche from fighting Mexico.

Next, the Comanche made peace with the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho in 1840. These tribes were moving south from the north. The agreement was very good for the Cheyenne and Arapaho. They could live and hunt on Comanche lands, which had many buffalo and horses. The Comanche even gave them gifts, including up to six horses for every Cheyenne and Arapaho man. This showed that the Comanche saw these tribes as strong rivals. It also showed that the Comanche needed more people and resources to control their large territory.

Dealing with Texas

South and southeast of Comancheria were the fast-growing Anglo-American communities in Texas. In the 1820s and 1830s, most Comanche raids in Texas were in the southern parts. These raids affected the Hispanic people around San Antonio, Laredo, and Goliad.

After Texas became independent from Mexico in 1836, the Comanche had to deal with the new Republic of Texas. Texas's first President, Sam Houston, knew a lot about Native Americans. He wanted to get along with the Comanche.

But Comanche raids continued. So, in 1838, Mirabeau B. Lamar was elected President. He wanted to fight the Comanche more aggressively. In March 1840, 35 Comanche chiefs were killed at a peace meeting in San Antonio. This event, known as the Council House Fight, led to many bloody attacks and battles. Hundreds of Comanches attacked and destroyed the towns of Victoria and Linnville in 1840. This was called the Great Raid of 1840.

Even though Texans showed they could fight back (like in the Battle of Plum Creek), military campaigns cost a lot of money. So, Texas became more willing to make peace. In 1844, Texas and the Comanche agreed to recognize Comanche lands. This left Comancheria as it was.

Focusing on Mexico

These agreements with the United States, neighboring tribes, and Texas allowed the Comanche to focus their attacks on the Mexican provinces south of the Rio Grande. Texas, the U.S., and other tribes could invade Comancheria. But Mexico was rich in horses and could not easily fight back. After 1836, any Mexican army going after the Comanche would have to cross Texas. Mexico did not recognize Texas as an independent country.

The Comanche attacked Mexico for several reasons: opportunity, money, and revenge. Their anger towards non-Comanches grew over decades of war. So, their raids on Mexico became more violent and destructive.

Comanche Raids in the 1840s

Before 1840, Comanche raids usually did not go far south of the Rio Grande. They often resulted in few deaths and the theft of a few thousand animals. But the threat was serious. In 1826, the Governor of northern Nuevo León ordered that no one should leave villages unless they were in groups of at least thirty armed men.

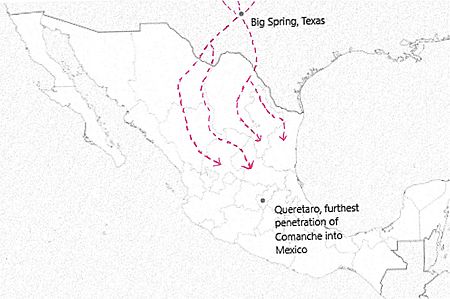

In the 1840s, Comanche raids became larger, deadlier, and went deep into Mexico. From September 1840 to March 1841, six Comanche armies invaded northern Mexico. Each army had between 200 and 800 warriors. The farthest raids reached San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas. These places were 400 miles south of the Big Bend, a common crossing point into Mexico. Reports said 472 Mexicans were killed and over 100 were taken captive in these six raids. Many others lost their homes and livelihoods. So much wealth was taken that the number of raids dropped for three years. But they started again even more strongly between 1844 and 1848, after the Comanche made peace with Texas.

The Comanche raided Mexico without fear of Mexico attacking their home in Texas. The Mexican government was busy with its own problems. It gave little help to its northern states to fight the Comanche. Local governments and ranchers tried to fight back with poorly armed militias. They also hired scalp-hunters, often Anglo-Americans or other Native Americans. In 1847, Durango offered 50 pesos for the head of a hostile Indian. In 1849, this was raised to 200 pesos, which was more than a laborer earned in a whole year.

Records show that between 1831 and 1848, 44 large Comanche raids (over 100 men each) went into Mexico. These raids killed 2,649 people and took 852 captives. About 580 captives were later returned. More than 100,000 animals were stolen. Any animals the Comanche could not steal, they killed. The Comanche also suffered many losses. They often seemed to look for a fight instead of just raiding. About 702 Comanche were killed, and 32 were captured. Comanches also got diseases from Mexican captives. The bloodiest year for raids was from July 1845 to June 1846. In that time, 652 Mexicans and 48 Comanches were killed. The Comanche had turned northern Mexico into a place where they could easily take resources.

Historians in the U.S. often described the Comanche as a simple tribe without clear political organization. But their success in building an empire on the Plains, their smart diplomacy, and their well-organized raids on Mexico show this was not true. Many small Comanche groups would gather in the summer. This was usually on the Red River or its branches in Texas or Oklahoma. They would plan and organize raiding parties. Comanches from as far away as the Arkansas River joined these raids. Other raiders included Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, and some Mexicans and Anglos who had left their own groups.

In the fall, small Comanche groups met at Big Spring. They traveled south along known trails, riding at night during the full moon. (Texans called a full moon in the fall a "Comanche Moon.") They crossed the Rio Grande either east or west of the Big Bend. Then they met up in the Bolson de Mapimi. This was a large, empty desert area. The Bolson had good grass, many springs, and mild winters. Many Comanche men brought their families there and stayed for the winter.

From the Bolson, the Comanche spread out in all directions. They went in small and large groups. They raided as far south as Jalisco and Querétaro in tropical Mexico. This was 600 miles from their usual Rio Grande crossing point. Each warrior took three or four horses, saving his best one for battle. Women and children often traveled with the men. They were ready to defend themselves if needed. One weakness of the Comanche was their strong desire to get back the bodies of their fallen warriors. They took big risks and suffered more losses because of this. They also sometimes seemed careless and were surprised by large groups of Mexican soldiers.

At the end of their yearly raids, usually in late winter or spring, the Comanche drove their stolen animals back to Texas. They sold or traded the horses and mules at American trading posts. Some posts were as far north as Bent's Fort in Colorado. They used the captives, mostly children, as workers. Boys took care of horse herds. Girls helped with household chores, like preparing buffalo skins for sale. Boys often grew up to be Comanche warriors. Girls often became one of several wives for Comanche men. A few captives were returned after money was paid.

Impact of the Raids on Mexico

In 1846, the government of Chihuahua described their difficult situation. They said, "We travel the roads…at their [the Comanches and Apaches] whim; we cultivate the land where they wish and in the amount they wish; we use sparingly things they have left to us until the moment that it strikes their appetite to take them for themselves." People feared the Comanche might even reach "the streets of Mexico City." In 1847, 200 Comanches boldly marched through the city of Durango and left without being challenged.

Also in 1847, a traveler named Josiah Gregg said that "the whole country from New Mexico to the borders of Durango is almost entirely depopulated." Many large farms and ranches were abandoned. People mostly stayed in towns and cities. When American troops invaded northern Mexico in 1846 and 1847, they found a ruined land and a discouraged people. There was little resistance to the Americans. Some Mexicans in the north might have hoped the U.S. would be better at fighting the "barbarians" than Mexican forces had been. The U.S. won the Mexican–American War (1846–48). Mexico gave up a huge amount of land to the U.S. This created new challenges for the Comanche.

After the Wars

Comanche raids into Mexico did not stop after Texas joined the United States and the Mexican–American War ended in 1848. But the Comanche faced a new situation. The U.S. now controlled the areas that would become California, Arizona, and New Mexico. One small benefit for Mexico from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was a promise from the U.S. to patrol the border. The U.S. would try to stop Native American invasions of Mexico. It also promised to outlaw trade in stolen Mexican goods and return Mexican captives.

Despite spending a lot of money, the U.S. had little more success than Mexico in stopping Comanche and Apache raids. In fact, the raids increased in the 1850s. In 1852, in one of the longest raids, the Comanche reached the Mexican state of Jalisco. This was near the Pacific Ocean, 600 miles from their usual Rio Grande crossing point. It was almost 1,000 miles from their home on the Great Plains. The U.S. stopped its promise to fight the raids in 1853. By 1856, officials in Durango claimed that Native American raids, mostly Comanche, had killed nearly 6,000 people in their state. They also said 748 people were taken captive, and 358 settlements were abandoned over 20 years.

The Comanche were at their strongest in the late 1840s. But their power quickly declined. In 1849, a cholera disease spread among the Plains Indians. Thousands of Comanches and their allies died. The 1850s brought a drought. This severely affected the buffalo herds in Comancheria, which were already being hunted a lot. The Comanche's huge horse herds also put a strain on their land. Soon, the Comanche were eating their horses for food.

The population of Texas grew very fast, reaching 600,000 by 1860. This meant more people moved onto Comanche lands. The U.S. army built five forts within Comancheria. This limited the Comanche's movement and reduced their hunting grounds. By the end of the 1850s, the Comanche population had dropped by about half since 1849. During the American Civil War (1861–1865), the Comanche pushed back the Texas frontier and took back some of their land.

The last Comanche raid into Mexico might have been in 1870. Reports say the Comanche killed 30 people near Lampazos, Nuevo Leon. After the Civil War, the Comanche were overwhelmed. The last of them, now only about 1,500 people, surrendered to the U.S. army in 1875. Their long-time raiding partners, the Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache, also surrendered.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra entre los Comanches y México para niños

In Spanish: Guerra entre los Comanches y México para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |