Josiah Gregg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Josiah Gregg

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | July 19, 1806 |

| Died | February 25, 1850 (aged 43) |

| Occupation | Merchant, explorer, naturalist, and author |

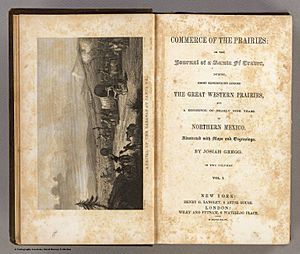

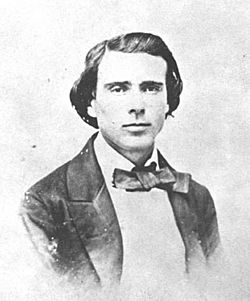

Josiah Gregg (born July 19, 1806 – died February 25, 1850) was an American merchant, explorer, and writer. He was also a naturalist, meaning he studied nature. Gregg is famous for his book, Commerce of the Prairies. This book describes the American Southwest and parts of northern Mexico.

He discovered many new plants during his travels and during the Mexican–American War. After the war, he went to California. He reportedly died near Clear Lake in 1850. This happened after a difficult journey where he helped find the location of Humboldt Bay.

Contents

Josiah Gregg's Early Life and Travels

Josiah Gregg was born on July 19, 1806, in Overton County, Tennessee. He was the youngest of seven children. When he was six, his family moved to Howard County, Missouri. At 18, Gregg worked as a schoolteacher in Liberty, Missouri. A year later, in 1825, his family moved to Independence. In Liberty, he studied law and surveying. However, his health became poor in 1830.

Because of his health, Gregg followed his doctor's advice. He traveled with a merchant group to Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1831. This journey started from Van Buren, Arkansas. In New Mexico, Gregg worked as a bookkeeper. He returned to Missouri in 1833. By spring, he was back on the road to Santa Fe. This time, he was a wagon master and a business partner.

In 1834, Gregg brought the first printing press to New Mexico. He sold it in Santa Fe, where it was used to print the territory's first newspaper. By 1840, Gregg had learned Spanish. He had crossed the plains between Missouri and Santa Fe four times. He also traveled into Mexico on the Chihuahua Trail. He had become a successful businessman.

On his last trip from Santa Fe, he chose a southern route to the Mississippi River. He left Santa Fe on February 25, 1840. He traveled with 28 wagons, 47 men, 200 mules, and 300 sheep and goats. In March, Pawnee attacked the group in Oldham County, Texas. A storm also scattered most of his animals. But the group continued east through Indian Territory to Fort Smith and Van Buren. In the early 1840s, Gregg lived briefly in Shreveport, Louisiana.

A few months later, he traveled through Oklahoma Territory. He went as far west as Cache Creek in Comanche land. During 1841 and 1842, Gregg explored Texas. He traveled up the Red River valley. On another trip, he went from Galveston to Austin. He then returned through Nacogdoches to Arkansas. He took notes on nature and human cultures. He also made money selling mules to the Republic of Texas.

He briefly settled in Van Buren as a partner in a store. He started writing his travel notes into a book. In the summer of 1843, he went to New York to find a publisher. He worked on his book while staying at the Franklin Hotel.

Commerce of the Prairies Book

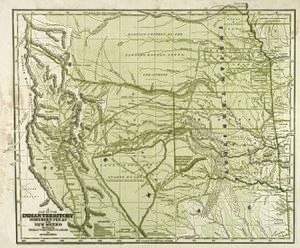

Gregg's book, Commerce of the Prairies, was published in two parts in 1844. It tells about his time as a trader on the Santa Fe Trail from 1831 to 1840. The book also describes the geography, botany (plants), geology (rocks), and culture of New Mexico. Gregg wrote about the local people and Native American cultures.

The book was an instant hit and made Gregg famous as a writer. It was printed many times and sold well in England. It was also translated into French and German. The map he made of the Santa Fe Trail was the most detailed at that time. His ideas about where the Red River started inspired a journey by Randolph B. Marcy and George B. McClellan in 1852.

Josiah Gregg and the Mexican–American War

In the fall of 1845, Gregg began studying medicine. He attended the University of Louisville School of Medicine. He graduated on March 9, 1846. By then, Gregg had learned to make daguerreotypes, which were early photographs. He became friends with artist John Mix Stanley.

Gregg joined General John E. Wool's Arkansas Volunteers. He worked as an unofficial news reporter and interpreter. In this role, he traveled through Chihuahua.

Life After the War

Gregg had planned to start a business with Samuel Magoffin. He left his belongings in Saltillo and traveled east in 1847 to buy goods. But Magoffin changed his mind. Gregg then went to Washington, D.C. He met President James K. Polk but was not impressed.

He took several steamships down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. Then he went up the Rio Grande and back to Saltillo in late 1847. Through the spring of 1848, he worked as a doctor for the first time since graduating.

Plant Collector and Discoveries

Many plant species in the Southwestern United States and Mexico are named greggii. This honors Gregg's important work in botany (the study of plants). One example is Ceanothus greggii, the desert ceanothus. He collected this plant in 1847.

He found and collected many other plants that were new to science. This happened on a trip to Mexico between 1848 and 1849. He sent these plant samples to his friend, botanist George Engelmann, in St. Louis, Missouri. Engelmann identified them.

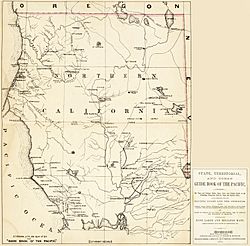

The California Gold Rush and Humboldt Bay

In 1849, Gregg joined the California Gold Rush. He sailed from Mazatlán to San Francisco. He tried canned food for the first time and liked it. He left his notes with his old partner, Jesse Sutton. He told Sutton what to do with them if he did not return from his trip. Soon after, he visited gold mines on the Trinity River.

On November 5, 1849, Gregg led a group of miners from Rich Bar. This was a mining camp on the Trinity River. They wanted to find "Trinity Bay" by crossing unknown land. The group included Gregg, Thomas Seabring, David A. Buck, J. B. Truesdale, Charles C. Southard, Isaac Wilson, Lewis Keysor Wood, and James Van Duzen.

Native Americans told them the Pacific Ocean was an eight-day journey. So, they packed ten days' worth of food. A few days later, David A. Buck found the South Fork Trinity River. There, they met a group of Native Americans who ran away. The group took smoked salmon from their village. That evening, eighty warriors came to Gregg's camp. They talked, and the Native Americans warned them not to follow the Trinity River to the sea. They said to go west and leave the river. This trail later became part of California State Route 299.

The group followed the river until it was too hard to pass. Then they went west. By November 13, their food was gone. They started eating deer and smoked game. They walked about 7 miles (11 km) a day. When they reached the redwood forests, they slowed to about 2 miles (3 km) a day. About six weeks after starting, they left the redwood forests. They saw the ocean at the mouth of a river they called the Little River. They explored a bit north, then turned south along the coast. They camped at Trinidad.

Leaving Trinidad, they crossed a large river. But the tired explorers did not want to wait for Gregg to figure out the exact location. So, they left without him. When he caught up, he was very angry. They named the river Mad River because of his outburst.

On December 20, 1849, David A. Buck was the first to discover what they called "Trinity Bay." A few months later, it became known as Humboldt Bay. The group walked around the bay. They passed the site of today's Arcata. They had a Christmas meal of elk meat near the Elk River. On December 26, they passed through today's Eureka. They reached the bay at a spot that would later be Fort Humboldt and Bucksport. Bucksport was named after David A. Buck.

Three days later, they found and named the Eel River. The name "Eel" is a mistake for the Pacific lamprey. Local Native Americans had caught these and shared them with the group. This was near where the Van Duzen River, named after James Van Duzen, joins the Eel.

Soon after, the group argued again about the best way to get back to San Francisco. About 20 miles (32 km) from the coast on the Eel River, the group split. Seabring, Buck, Wilson, and Wood followed the Eel River. Gregg, Van Duzen, Southard, and Truesdale went to the coast. L.K. Wood was badly hurt by a grizzly bear while stuck in a snow-covered camp. His friends carried him on a horse. They traveled south along the South Fork of the Eel. When they reached Santa Rosa, news of their discovery spread.

Gregg's group had a harder time. Wood wrote: "They tried to follow the mountains near the coast. But they were very slow because of the snow on the high ridges. The country was very rough, with many steep points and deep canyons. After struggling for several days, they decided to leave that route. They headed east toward the Sacramento valley. They had very little ammunition. They almost died from hunger. Mr. Southard told me that Dr. Gregg grew weaker. One day, he fell from his horse and died in a few hours without speaking. He died from starvation. He had not eaten meat for several days. He had been living only on acorns and plants. They dug a hole with sticks and buried him. Then they piled rocks on his grave to keep animals away. They reached the Sacramento valley a few days after we reached Sonoma valley. This was the end of our journey."

Southard's story of burying Gregg might not be the full truth. Other reports say Gregg died on February 25 near Clear Lake, California. This was due to poor health and the hard journey. Another story suggests he survived for a short time in a Native American village. In any case, his papers, tools, and plant samples were lost.

Josiah Gregg's Legacy

Gregg's expedition in 1849–1850 is credited with finding Humboldt Bay again by land. This led to people settling there. The Gregg party's trip also led to an expedition in 1850 by Colonel Redick McKee. This expedition aimed to make treaties with Native Americans in Northern California. However, these treaties were never officially approved.

About eighty plant names were first given to honor Gregg. As of 2002, 47 plant species from Mexico and the Southwest still have the name greggii.

A portrait of Gregg, painted by Herndon Davis, is in the Palace of the Governors. This is a history museum in New Mexico.

|

See also

In Spanish: Josiah Gregg para niños

In Spanish: Josiah Gregg para niños