John Horse facts for kids

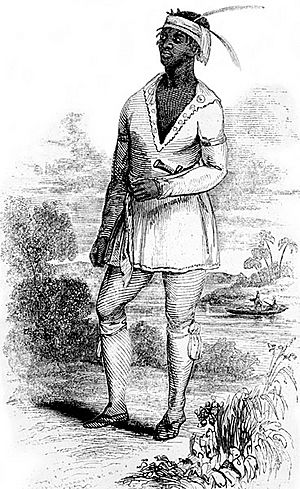

John Horse (born around 1812, died 1882) was a very important leader. He was also known as Juan Caballo or Gopher John. John Horse was part African and part Seminole Indian. He fought with the Seminoles in the Second Seminole War in Florida. He became a key leader during this long war. This happened after many other leaders were lost, and the main Seminole chief, Osceola, was captured by the American army.

Contents

John Horse's Story

Growing Up in Florida

John Horse, called Juan when he was young, was born around 1812 in Florida. He had a mix of Spanish, Seminole, and African family roots. He lived near a place now called Micanopy. His father was a Seminole trader named Charley Cavallo. The name "Horse" is thought to be a translation of "Cavallo," which means horse in Spanish. His mother was likely of African descent. John also had a sister named Juana. It seems his father did not treat John or his sister as slaves.

When John was born, the War of 1812 was happening. He and his family probably lived near the Suwannee River. American General Andrew Jackson attacked the area. He forced many Native American groups and their Black allies to move. John's family was likely displaced by these actions. He later appeared in records as a teenager near Tampa.

John Horse grew up among the Oconee Seminole people. He learned to hunt, fish, and track animals. He became very skilled with a bow and arrow and a rifle. Later, he was known as an excellent shot in battle. Unlike many others, he also learned to read and write. He could speak English, Spanish, and the Hitchiti language. He likely also spoke Muscogee, the language of Osceola, the Seminole war chief. John Horse often helped Osceola talk with the Americans.

Fighting in the Seminole Wars

The First Seminole War (1817–1818) happened when John was a child. He and his family probably moved south towards Tampa Bay. There, John met American soldiers at Fort Brooke. An officer named Major George M. Brooke found out John had tricked his cook by selling the same tortoise (a "gopher") multiple times! Major Brooke was kind and let John go. This event gave John his nickname, "Gopher John."

Later, John Horse fought against the American army with the Seminoles. The Second Seminole War (1835–1842) started because American settlers wanted Native American lands. John Horse became a field officer for the Seminoles. He translated for leaders who didn't speak English. He also became a lower-level war chief. Because he was smart and good with languages, John Horse often helped with talks between the Seminoles and the U.S. Army.

By 1838, John Horse decided the war could not be won. He surrendered to U.S. troops. He may have done this after losing his first wife. The Black Seminoles were promised freedom if they stopped fighting. They would also be moved to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

General William J. Worth later gave John Horse papers that freed him a second time. This was for his help to the U.S. Army as a translator and scout. General Thomas Sydney Jesup had made the first promise of freedom to all who surrendered. So, John Horse had at least two legal claims to freedom. This would become important later. However, his second wife, Susan, and their children were not freed by his later service. They only had Jesup's earlier promise. This meant they were still at risk from slave catchers.

John Horse and other Seminoles were sent by ship from Tampa Bay to New Orleans. From there, they traveled up the Mississippi River to Indian Territory. They joined other Seminole and Black Seminole people. John Horse quickly became a leader among the Black Seminoles. This was because he had good relations with Americans, was a strong leader, and spoke many languages.

Life in Indian Territory

New Challenges and Old Problems

In the new territory, John Horse sometimes worked for the army as an interpreter. He also helped leaders talk to each other. In 1839, he went back to Florida. The army asked him to convince other Seminole fighters to surrender. He helped his old friend, Chief Coacoochee, to accept moving to Indian Territory. John Horse returned to Indian Territory in 1842.

Around 1843, the Seminole leaders in Indian Territory voted to free John Horse. This was because of his great service to the Seminole people during the war. So, John Horse had been freed three times: by General Jesup, by General Worth, and by the Seminole leaders. But only Jesup's promise applied to John Horse's wife, Susan, and their children. This promise soon faced serious challenges.

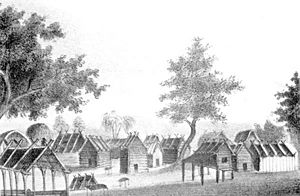

Problems arose because the Seminoles were placed on land given to the Creek Indians. The U.S. government did not fully understand the differences between the two groups. The Creek people practiced chattel slavery, like in the American South. The Seminoles did not. Free Black Seminoles living on Creek land caused tension. Their presence threatened the Creek's slave system. It also made them targets for slave catchers.

Creek slave owners and others began raiding Black Seminole settlements. They kidnapped people to enslave them. John Horse quickly became a leader in fighting back against these attacks. He spoke for his fellow Black Seminoles. In one case, a war veteran named Dembo Factor was captured. John Horse and Coacoochee protested. The army helped get Factor released. But the slave raids continued, and tensions grew.

Finding a Solution

In 1844, John Horse went to Washington, D.C., with Coacoochee. They wanted a separate land grant for the Seminoles. They argued that Seminoles had been a separate people for a long time. They did not get the support they needed. John Horse then traveled to Washington again, this time alone. He wanted General Jesup to keep his promises. Jesup felt bad about how Osceola had been captured. He tried to help, but there was political pressure to cancel his promise of freedom to the Black Seminoles.

Jesup then visited Indian Territory himself. He made a list of everyone who had surrendered under his order. He also offered them work building new facilities at Fort Gibson. Many Black Seminoles moved near the fort for army protection. Even after the work was done, they stayed there. This was because slave catchers from Creek, Cherokee, and white groups kept attacking them.

John Horse was even attacked by unknown people and shot. After this, the officer at Fort Gibson invited John and his family to live inside the fort. John accepted. The Seminole sub-agent, Marcellus Duval, wanted to profit from the Black Seminoles being enslaved again. He argued that the army should not protect them.

Threat of Slavery Again

Later, the U.S. Attorney-General, John Y. Mason, made a ruling. President James K. Polk asked him to decide if Jesup's freeing of the Seminole slaves was legal. Duval and his allies pushed for this ruling. Mason, who was from the South, ruled that Jesup's order was illegal. He said it took away the Seminole owners' legal property. This meant that the reason many Black Seminoles had surrendered peacefully was suddenly taken away.

Seminole slavery in Florida was different from the American South. It was more like a feudal system. Black Seminoles often lived in their own towns. They carried weapons and fought alongside the Seminoles. They gave some crops to the chief each year. Otherwise, their lives were very similar to other Seminoles. This changed in Indian Territory. The Seminoles had to settle on fixed land and farm.

Many Seminoles then became interested in the chattel slavery model. They were also becoming poorer. The Black Seminoles were often better farmers and craftspeople. So, getting slave labor became appealing to them. Marcellus Duval worked hard to restore the Seminoles' claims over their former allies. He hoped to benefit from this himself.

With Mason's ruling, those freed by Jesup were now considered enslaved again. Duval and the pro-Creek Seminoles demanded their return. More than 280 Black Seminoles, including John Horse's family, were now at risk. Duval arranged for the Black Seminoles at Fort Gibson to be forced back to their "owners." He had an agreement with the pro-Creek Seminole leaders. They would give a large number of the re-enslaved Black Seminoles to Duval's lawyer brother. They hoped to make money by selling these people.

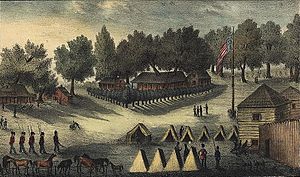

The army received orders to remove the Black Seminoles from Fort Gibson. They were to be forced back into slavery. John Horse had run out of options. Even the government and army were against him.

Moving to Mexico

The army generals liked John Horse, but they had to follow orders. The War Department and the Bureau of Indian Affairs were against the Black Seminoles. John Horse joined Coacoochee again. They tried to stop the pro-Creek leaders from taking over and enslaving the Black Seminoles. The generals delayed the orders from Washington. But when Chief Micanopy died, the army could no longer wait. John Horse led the Black Seminoles away from Fort Gibson.

Instead of going to the place Duval wanted, John Horse and another scout, Toney Barnet, settled their people at a place called Wewoka on the Little River. This was farther from the Creek and the Seminole agency. They built defenses against slave catchers. John Horse and Barnet planned to get Marcellus Duval out of the way. Barnet offered to go with Duval on a trip to Florida.

While Duval was gone, John Horse quickly made a plan with Coacoochee. Coacoochee was unhappy because he wasn't chosen to replace Micanopy. In the middle of the night, they led over a hundred Black Seminoles and many Seminoles out of Indian Territory. They went south across the Red River into Texas. Their journey across Texas took almost a year. Duval's slave catchers and the Texas Rangers chased them. The Texas governor had authorized the Rangers to capture them. From October 1849 to summer 1850, Horse and Coacoochee led the group south. They were joined by some Kickapoo Indians. They also faced attacks from the Comanche.

Reaching the Border

After a battle with the Comanche, the group had to cross a desert. They met Major John T. Sprague near the Mexican border. Sprague had known John Horse and Wild Cat in Florida. The three men talked through the night. But the Indians learned that someone from the army camp had told the Texas Rangers about them.

Before dawn, John Horse and Coacoochee woke their people. They secretly left the camp and rushed to the Rio Grande. They built rafts to cross the river. They were still crossing when the Rangers arrived. But it was too late. The Seminole, Black Seminole, and Kickapoo people made it across. They contacted officials in the Mexican state of Coahuila. On July 12, 1850, they were given land and military positions in the Mexican army. In return, they promised to fight invaders and raiders from Texas.

Later Life and Legacy

John Horse and Coacoochee worked together for the Mexican government. But Coacoochee soon died from smallpox. Many Seminole and Kickapoo people left. John Horse stayed with his people and became their main leader.

After the American Civil War and the end of slavery in the U.S., the U.S. Army hired many Black Seminoles from Mexico as scouts. John Horse was too old for active service. But he remained the leader of his people. He still led them in fighting raiding parties from the north.

In one famous event, John Horse returned to find his settlement attacked. Many of his people had been captured. He led about forty men and teenage boys to chase the raiders. The raiders tried to trick them into a canyon. But John Horse was a clever commander. He sensed the trick and stopped his men. The raiders then attacked head-on. John Horse's men had old, single-shot rifles. Their first shots did not stop the raiders. As his men reloaded, John Horse stepped forward. He aimed his empty rifle at the oncoming chief. John Horse was known as an excellent shot. The chief lost his nerve and turned his horse, breaking the charge. This gave John Horse's men time to reload. In the end, the raiders fled, and John Horse's people were rescued.

As John Horse got older, many of his people moved back to Texas. They worked for the U.S. Army as scouts. These families settled near Fort Clarke, in what is now Brackettville.

Death

In his seventies, John Horse faced another problem. Local landowners tried to take the land the Mexican government had given the Seminole settlers. John Horse rode to Mexico City to get the government to confirm their land grant. He was never heard from again. It is believed he died on this trip in 1882. Today, hundreds of Black Seminole descendants, called Mascogos, still live in Coahuila, Mexico.

See also

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |