Anishinaabe facts for kids

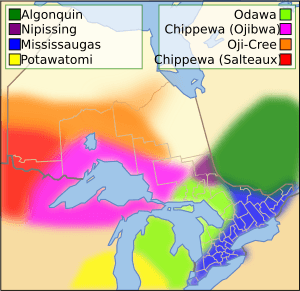

Homelands of Anishinaabe and Anishinini, ca. 1800

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Canada (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba) United States (Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin) |

|

| Languages | |

| English, French, Ojibwe (Including Odawa), Potawatomi, and Algonquin | |

| Religion | |

| Midewiwin, Catholicism, Methodism, and others | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Odawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Oji-Cree, Algonquin peoples and Métis |

| Person | Anishinaabe |

|---|---|

| People | Anishinaabeg |

| Language | Anishinaabemowin |

| Country | Anishinaabewaki |

The Anishinaabeg are a group of indigenous peoples who share similar cultures. They live in the Great Lakes area of Canada and the United States. This group includes the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Mississaugas, Nipissing, and Algonquin peoples.

The Anishinaabe speak Anishinaabemowin, which are languages from the Algonquian language family. When Europeans first arrived, the Anishinaabe lived in the Northeast Woodlands and Subarctic regions. Some later moved to the Great Plains.

The word Anishinaabe can mean "people from whence lowered" or "the good humans." It refers to those who follow the right path given by the Creator or Great Spirit. Basil H. Johnston, an Ojibwe historian, said it means "Beings Made Out of Nothing" or "Spontaneous Beings." The Anishinaabe believe they were created by a divine breath.

It's important to know that Anishinaabe is not the same as Ojibwe. Anishinaabe is a larger group that includes many different tribes.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name ᐊᓂᔑᓈᐯ Anishinaabe can be spelled in many ways. This is because different spelling systems show how vowels or consonants are pronounced. For example, Anishinaabeg or Anishinabek are plural forms, meaning "the Anishinaabe people." Forms ending in -e are singular.

Sometimes, the name is shortened to Nishnaabe, especially by Odawa people. The Potawatomi people, who have long been allies with the Odawa and Ojibwe, use the similar word Neshnabé. The Nipissing, Mississaugas, and Algonquin are Anishinaabe, but they are not part of the Council of Three Fires (which we'll learn about soon!).

The Oji-Cree people are closely related to the Ojibwe and speak a similar language. They often call themselves Anishinini and their language Anishininiimowin.

Not all Anishinaabemowin speakers call themselves Anishinaabe. For example, Ojibwe people who moved to the prairie provinces of Canada call themselves Nakawē(-k) and their language Nakawēmowin. The French called this group the Saulteaux.

Anishinaabe Clans

In Anishinaabe culture, miigis are special beings. Six of these miigis created different doodem (clans) for the people. A clan is like a large family group. The six main clans were:

- Awaazisii (Bullhead)

- Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, like a Crane)

- Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck)

- Nooke (Tender, like a Bear)

- Moozoonii (Little Moose)

- Waabizheshi (Marten)

Anishinaabe stories say that a powerful miigis gave the people a prophecy. It said the Anishinaabeg needed to move west to keep their traditions alive. This was because many new people would soon arrive. Their journey west followed a path of "Turtle Islands," which were confirmed by special shells.

After getting permission from their allies, the Anishinaabeg moved inland. They traveled along the St. Lawrence River to the Ottawa River, then to Lake Nipissing, and finally to the Great Lakes.

Their first stop was Mooniyaa, where Mooniyaang is today. Here, the Anishinaabeg split into two groups. One group settled along the Ottawa River. The main group continued to the "second stopping place" near Niagara Falls.

By the time they reached their "third stopping place" near Detroit, the Anishinaabeg had formed six distinct nations: Algonquin, Nipissing, Missisauga, Ojibwa, Odawa, and Potawatomi. The Odawa made Manitoulin Island their cultural center, while the Ojibwe centered in the Sault Ste. Marie area.

As they traded more with the French and British, and gained European small arms, members of the Council of Three Fires expanded their territory. They moved south to the Ohio River, southwest along the Illinois River, and west along Lake Superior, Lake of the Woods, and the northern Great Plains. During this western movement, the Ojibwa split again, forming the Saulteaux, who became the seventh main branch of the Anishinaabeg.

As the Anishinaabeg moved, they welcomed other related Algonquian peoples into their nation. This included groups like the Noquet and Mandwe. Other groups can often be identified by their Doodem (Clan). For example, the Migizi-doodem (Bald Eagle Clan) often means ancestors from the present-day United States. The Ma'iingan-doodem (Wolf Clan) often means ancestors from the Santee Sioux.

Today, Anishinaabe peoples live across North America, mainly around the Great Lakes and Lake Winnipeg.

After European newcomers arrived, many Anishinaabeg chiefs signed treaties with the Canadian and United States governments. These treaties were often in languages the chiefs did not speak or read. For example, Treaty 3 in Canada was signed in 1873 between the Anishinaabe (Ojibwa) people west of the Great Lakes and the Canadian government. Because of treaties and forced moves, some Anishinaabeg now live in Kansas, Oklahoma, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Montana in the United States. In Canada, they live in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Anishinaabe History

Where They Came From

According to Anishinaabe traditions and ancient wiigwaasabak (birch bark scrolls), the people came from the eastern parts of North America, along the East Coast. In old stories, their homeland was called Turtle Island. This name comes from the belief that the Earth or North America rests on the back of a giant turtle.

Anishinaabe oral history says they are descendants of the Abenaki people, whom they call "Fathers." Another story says the Abenaki are descendants of the Lenape, so they are called "Grandfathers." However, Cree stories often say the Anishinaabe are their descendants.

Anishinaabe traditions have several origin stories. One story tells of seven great miigis (shining beings in human form) who appeared to the Anishinaabeg in the Waabanakiing (Land of the Dawn, or Eastern Land). These beings taught the people about the midewiwin way of life. One miigis was too powerful and returned to the ocean, leaving six miigis to teach the people.

The Anishinaabeg are one of the First Nations in Canada.

Meeting European Settlers

The first Anishinaabeg to meet Europeans were those of the Three Fires Confederation. This group lived in areas that are now Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania in the United States, and southern Ontario and Quebec in Canada.

The Anishinaabeg and Europeans interacted a lot. They traded furs, and the Anishinaabeg often allied with Europeans in their conflicts. Europeans traded goods for furs and hired Anishinaabeg men as guides. Sometimes, Anishinaabeg women married fur traders. Their children later formed the Métis ethnic group.

French Explorers

The first Europeans in the Great Lakes area were French voyageurs. These skilled canoe paddlers moved furs and goods across North America's lakes and rivers. They gave French names to many places in present-day Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin. The French were mainly trappers and traders. They often struggled to build lasting settlements and relied on indigenous groups for supplies to survive.

British Influence

The Ojibwa, Odawa, and Potawatomi tribes developed their unique identities after the Anishinaabeg reached Michilimackinac during their journey west. An elder named Shop-Shewana dated the start of the Council of Three Fires to 796 AD at Michilimackinac.

In this council, the Ojibwa were called the "Older Brother," the Odawa the "Middle Brother," and the Potawatomi the "Younger Brother." When these three nations are listed in this order, it refers to the Council of Three Fires. Each tribe had a special role: the Ojibwa were "keepers of the faith," the Odawa were "keepers of trade," and the Potawatomi were "keepers of the fire."

The Ottawa (also Odawa) are a Native American and First Nations people. The Ojibwe language is the third most spoken Native language in Canada and the fourth most spoken in North America. Potawatomi is spoken around the Great Lakes and in Kansas, USA, and by a small number of people in southern Ontario, Canada.

The Three Fires Council met often, especially at Michilimackinac because it was in a central location. They met for military and political reasons and kept good relationships with other nations, both Anishinaabeg and non-Anishinaabeg. After Europeans arrived, the French built Fort Michilimackinac in the 18th century. After the Seven Years' War, the British took over the fort and used it for trade.

Through their totem system (a totem is a symbol that represents a group) and by promoting trade, the Council usually lived peacefully with their neighbors. However, sometimes disputes led to wars. The Council fought against the Iroquois Confederacy and the Sioux. During the Seven Years' War, they fought with France against England because they had long-standing trade ties with the French. Before Europeans, warfare was often ceremonial, like honor duels, and didn't always result in deaths or gaining land.

Later, the Anishinaabeg formed a similar relationship with the British. They created the Three Fires Confederation to deal with conflicts from settlers moving onto their lands and ongoing tensions with the British Canadian government, and later the new United States government. During this time, new diseases like smallpox, which were brought by Europeans, caused great suffering and loss of life among the Anishinaabe people.

United States

During the Northwest Indian War and the War of 1812, the Three Fires Confederacy fought against the United States. Many Anishinaabeg who were refugees from the Revolutionary War, especially Odawa and Potawatomi, moved north to British-held areas.

Those who stayed east of the Mississippi River were affected by the 1830 Indian Removal policy of the United States. The Potawatomi were most impacted by this policy. The Odawa had already moved away from settler paths, so only a few of their communities were forced to move. For the Ojibwa, attempts to remove them led to the Sandy Lake Tragedy, where hundreds died. Some Potawatomi avoided removal by hiding in Ojibwa areas.

William Whipple Warren (1825–1853) was a man of mixed Ojibwe and European descent. He became an interpreter and a legislator in the Minnesota Territory. He was a great storyteller and historian who collected many Ojibwe stories. He wrote History of the Ojibway People, which was published in 1885. Even though he had an American father and education, the Ojibwe considered him a "half brother" because he knew their language and culture so well, and his mother was of mixed Ojibwe-French heritage. His work shared much about Ojibwe culture and history.

Warren identified the Crane and Loon clans as the two main leadership clans among his mother's Anishinaabe people. The Crane Clan handled relationships with other nations, and the Loon Clan managed internal community matters. Warren believed that the British and U.S. governments damaged the clan system when they forced Native nations to adopt new forms of government. He thought this led to many conflicts among the Anishinaabe.

After the Sandy Lake Tragedy, the U.S. government changed its policy to moving tribes onto reservations, often combining several communities. Conflicts continued through the 19th century. After the Dakota War of 1862, many Anishinaabeg communities in Minnesota were moved and combined further.

Relationships with Neighbors

Other Indigenous Groups

There are many Anishinaabeg reserves and reservations. In some places, the Anishinaabeg share their lands with other groups like the Cree, Dakota, Delaware, and Kickapoo. Some Anishinaabeg who joined the Kickapoo tribe now identify as Kickapoo in Kansas and Oklahoma. The Prairie Potawatomi were Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi from Illinois and Wisconsin who were moved to Kansas in the 1800s.

The Anishinaabe of Manitoba, especially those along the east side of Lake Winnipeg, have had long-standing historical conflicts with the Cree people.

Canada

The Anishinaabe of Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec have spoken out against projects like the Energy East pipeline. The Chippewas of the Thames First Nation challenged the Canadian government's right to hold a pipeline hearing without their agreement. In June 2015, several Anishinaabe peoples declared their reclaimed sovereignty over the Ottawa River valley because of this project.

United States

The relationship between the Anishinaabe communities and the United States government has been getting better since the Indian Reorganization Act. However, some Anishinaabe communities still face challenges with state and local governments, and with non-Native American groups.

Today, the Anishinaabe are working to bring back the clan system as a way to govern themselves. They are inspired by Ojibwe educator Edward Benton-Banai, who believes in education based on one's own culture. They think using the clan system will help bring back their culture and political strength. A clan originally meant an extended family. In this system, clans were represented by spokespeople at yearly meetings. More recently, clans have been linked to personality traits, focusing on the strengths people can offer the community. For example, the deer clan might be known for hospitality, while the crane or eagle clan might be known for leadership. Discussions about how to change current governments to better match their traditional ways are ongoing across Anishinaabe Aki (Anishinaabe land).

Some big issues the Anishinaabe communities face include keeping their culture and language alive, getting full federal recognition, dealing with disputes within their own governments, protecting treaty rights, and improving health, education, and employment.

Anishinaabe Culture

Teachings of the Seven Grandfathers

The Teachings of the Seven Grandfathers are very important in Native culture, especially for the Anishinaabeg. They are seen as the basic rules for their way of life. These teachings have been passed down for centuries through storytelling by elders. They have shaped the Anishinaabeg way of life and continue to do so. These teachings can be adapted for different communities and are used by many organizations, schools, and tribes.

Nibwaakaawin: Wisdom (Beaver)

To value knowledge is to have wisdom. Wisdom is a gift from the Creator to be used for the good of all people. In Anishinaabemowin, this word also means "prudence" or "intelligence." Some communities use Gikendaasowin, which also means "intelligence" or "knowledge."

Zaagi'idiwin: Love (Eagle)

To find peace is to know love. Love should be unconditional. When people are struggling, they need love the most. In Anishinaabemowin, this word means that love is shared between people. Some communities use Gizhaawenidiwin, which can mean "love" or "zeal."

Minaadendamowin: Respect (Buffalo)

To honor all living things is to have respect. Everything in creation should be treated with respect. If you want to be respected, you must also show respect to others. Some communities use Ozhibwaadenindiwin or Manazoonidiwin.

Aakode'ewin: Bravery (Bear)

To be brave means to face challenges with honesty and strength. In Anishinaabemowin, this word means "having a fearless heart." It means doing what is right, even when it's difficult. Some communities use Zoongadiziwin ("having a strong casing") or Zoongide'ewin ("having a strong heart").

Gwayakwaadiziwin: Honesty (Raven)

Being honest in a situation shows bravery. You should always be honest in your words and actions. If you are honest with yourself first, it will be easier to be honest with others. In Anishinaabemowin, this word can also mean "righteousness."

Dabaadendiziwin: Humility (Wolf)

Humility means seeing yourself as a special part of Creation, no better or worse than anything else. In Anishinaabemowin, this word can also mean "compassion." Some communities use Bekaadiziwin, which can also mean "calmness," "meekness," "gentility," or "patience."

Debwewin: Truth (Turtle)

Truth is understanding all of these teachings. You should speak the truth and not mislead yourself or others.

Storytelling

The Anishinaabeg have a strong tradition of oral storytelling. Stories are a key part of their culture because they share wisdom and knowledge. They also encourage "respectful individualism," meaning people don't force their ideas on others. Instead of directly saying what's right or wrong, stories share history and cultural truths, including the Teachings of the Seven Grandfathers. Stories often "provide important lessons for living and give life purpose, value, and meaning." They can include religious teachings, cultural insights, history, and Indigenous "truths." By understanding traditional stories, people can better understand themselves and their world.

Storytelling is flexible. Storytellers think about their audience and keep the story easy to understand. Both the teller and the listener are active. Stories are not fixed; people can add to them and change them over time. There is no single "final form" for any story.

Before telling a story, Elders often mention the Elders who told the story before them. They might say, "This is what they used to say."

Storytelling also helps Anishinaabeg children learn to express themselves. Allowing children to share stories is seen as empowering them. It shows that even children have something valuable to share.

Stories are usually shared during the winter when there is less outdoor work and animals are sleeping.

The Trickster

The Trickster is a common character in Anishinaabeg stories. This character has many names, like Coyote, Raven, Wesakejac, Nanabozo, and Glooscap. The Trickster can appear in many forms and genders. Stories with the Trickster often use humor and silliness to teach important lessons.

The Trickster helps teach cultural lessons by "learning the hard way." In these stories, the Trickster often gets into trouble by ignoring cultural rules or by giving in to negative human traits. The Trickster seems to learn lessons the hard way, or sometimes not at all! But the Trickster also "has the ability to do good things for others and is sometimes like a powerful spiritual being." Trickster stories remind us about the good power of being connected within family, community, nation, culture, and land.

Life Before the 1800s

Before Europeans arrived and until at least the 1800s, many Anishinaabeg were farmers. For example, the Odawa, who lived around Michilimackinac, grew corn in the summers. In winter, smaller family groups often moved south to hunt. In spring, they tapped sugar maples for syrup. Then they returned to their main villages to prepare for the lake sturgeon spawning season and planting.

The Anishinaabe were known for their skill in making and using canoes, and they traded widely.

Their family system was patrilineal, meaning children belonged to their father's clan. Most Anishinaabe doodemag (clans) practiced exogamy, meaning people married outside their own clan. For the first few years of marriage, a husband would live with his wife's family. Then, they would usually return to the husband's people. Because of this, many Anishinaabe villages included people speaking different languages, not just from different clans, but also from entirely different peoples, like the Huron and sometimes even the Sioux.

Education

In June 1994, the Anishinabek Grand Council directed that the Anishinabek Educational Institute (AEI) be created. This institute provides post-secondary education, with satellite campuses and community-based learning.

In August 2017, the Anishinabek Nation in Ontario and the government of Canada signed an agreement. This agreement allows the Anishinabek Nation to control the school curriculum and resources for their Kindergarten to Grade 12 education system in 23 communities.

About 8% of Anishinabek students attend schools on their reserves.

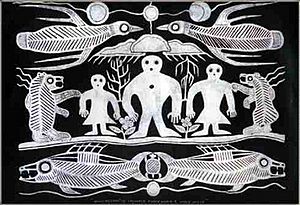

Images for kids

-

Pictograph of a canoe (top left), Mishipeshu (top right), and two giant serpents (chignebikoogs), panel VIII, Agawa Rock, Lake Superior Provincial Park, Ontario, Canada

See also

In Spanish: Anishinaabe para niños

In Spanish: Anishinaabe para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |