Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Reconstructed earthworks at Moores Creek Battlefield |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,050 militia | Start of march: 1,400–1,600 Battle: 900–1000 |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 killed 1 wounded |

50 killed or wounded 850 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge was a small but very important battle during the American Revolutionary War. It happened near Wilmington, North Carolina, on February 27, 1776. In this battle, a group of American fighters from North Carolina defeated British supporters. This victory was a key moment for the American Revolution in North Carolina. America declared its independence less than five months later.

Before the battle, people in North Carolina were choosing sides. Some were Loyalists, who wanted to stay loyal to the British King. Others were Patriots, who wanted America to be independent. When news arrived in early 1776 that British soldiers were coming, the British governor, Josiah Martin, told his Loyalist supporters to get ready. The Patriots quickly gathered their own soldiers to stop the Loyalists from joining the British. The Loyalists, who were not well-armed, were forced to fight at Moore's Creek Bridge.

The battle was short and happened early in the morning. Loyalist soldiers, many of them Scottish Highlanders, charged across the bridge with swords. They shouted in their language, Scottish Gaelic. But the Patriots were ready. They fired their muskets and cannons. Two Loyalist leaders were killed, and another was captured. The Loyalist force quickly broke apart and ran away. After the battle, many Loyalists were arrested. This made it hard for the British to find more supporters in North Carolina. The state was not threatened by British forces again until 1780.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

British Look for Supporters

In 1775, tensions were growing between the American colonies and Great Britain. North Carolina's royal governor, Josiah Martin, wanted to build a strong group of Loyalists. He hoped to get support from Scottish settlers and other people who were unhappy with the Patriot movement. Governor Martin asked London for permission to gather 1,000 men, but his request was turned down. Still, he kept trying to find Loyalists.

Around the same time, a Scottish officer named Allan Maclean of Torloisk asked King George III if he could recruit Scottish Loyalists in America. He got permission to form a regiment called the Royal Highland Emigrants. Two officers, Donald MacLeod and Donald MacDonald, were sent to North Carolina to find new soldiers. They were already aware of another Scottish leader, Allan MacDonald, who was also gathering Loyalists.

When MacLeod and MacDonald arrived, local Patriot leaders were suspicious. But the officers said they were just visiting friends. In reality, they were British officers on a secret mission. They were allowed to continue without being arrested. Major Donald MacDonald was an experienced British Army officer, 65 years old. He had fought in Scotland before and many Scottish settlers in North Carolina knew him. They were ready to listen to him.

On January 3, 1776, Governor Martin learned that more than 2,000 British soldiers were coming from Ireland. They were expected in mid-February. Governor Martin quickly ordered all his recruiters to have their men ready by February 15. He also made Major Donald MacDonald the main commander of all British and Loyalist soldiers in North Carolina. MacDonald became a Brigadier General.

Governor Martin was very hopeful for an easy Loyalist victory. He sent out messages telling "all the King's loyal subjects" to join the King's army. He warned that those who refused would face serious trouble. This warning reminded Scottish Highlanders of harsh punishments they had faced in Scotland in the past.

On February 1, 1776, Brigadier General MacDonald raised the King's flag in Cross Creek (now Fayetteville). They held parties to get people excited about fighting. But behind the scenes, the Loyalist leaders disagreed. Some Scottish leaders wanted to wait for the British troops to arrive. Other Loyalist groups wanted to move right away. The second group won the argument.

When the Loyalists gathered on February 15, 1776, they had about 3,500 men. Many were Scottish Highlanders, wearing traditional clothes and playing bagpipes. They came from different Scottish clans. A famous Scottish woman, Flora MacDonald, gave a speech in Gaelic to inspire them.

However, the number of Loyalists quickly dropped. Many Highlanders had been promised they would meet British troops and didn't want to fight alone. When they marched from Cross Creek on February 18, Brigadier General Donald MacDonald led between 1,400 and 1,600 men. This number kept shrinking as more men left the group.

Patriots Get Ready

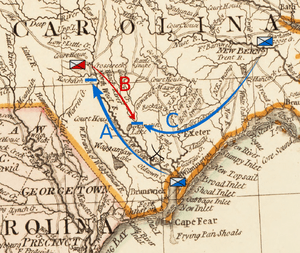

Meanwhile, the Patriots in North Carolina heard about the Loyalist gathering. They had already formed their own army units. Colonel James Moore led the 1st North Carolina Regiment. Local groups of citizen soldiers, called militia, were led by Alexander Lillington and Richard Caswell. On February 15, the Patriot forces began to move.

Colonel Moore led 650 Patriot militiamen from Wilmington. Their goal was to stop the Loyalists from reaching the coast. They camped near Rockfish Creek. General MacDonald learned they were there and sent a message asking the Patriots to give up. Colonel Moore replied, telling the Loyalists to give up their weapons and support the American cause.

At the same time, Caswell led 800 militiamen toward the area. Many of these Patriot fighters were from families who had lived in North Carolina for generations. They were fighting for their homes and their future. In contrast, the Loyalist army was mostly Scottish Highlanders who had arrived more recently.

Loyalist March to the Bridge

MacDonald's first path was blocked by Moore. So, he chose another route that would lead his forces to the Widow Moore's Creek Bridge. On February 20, he crossed the Cape Fear River and destroyed the boats. This stopped Moore from using them. His forces then headed for Corbett's Ferry.

On Moore's orders, Caswell reached Corbett's Ferry first and blocked the crossing. Moore also sent Lillington with 150 militiamen and 100 rangers to the Widow Moore's Creek Bridge. These men marched quickly and started digging defensive positions on the east side of the creek. Moore followed with his slower troops, but they arrived after the battle.

When MacDonald's forces reached Corbett's Ferry, they found Caswell blocking the way. MacDonald prepared for battle, but a local person told him about another crossing a few miles up the river. On February 26, MacDonald sent some of his men to pretend they would cross at the ferry. Meanwhile, he led his main force to the other crossing and headed for Moore's Creek Bridge.

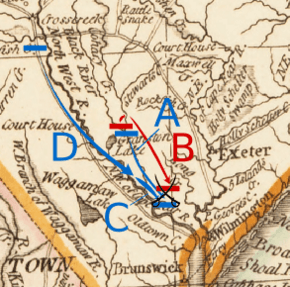

Caswell realized MacDonald had tricked him. He quickly moved his men about 10 miles to Moore's Creek. They arrived just a few hours before MacDonald. MacDonald sent a messenger to the Patriot camp, demanding they surrender. The messenger also secretly checked the Patriot defenses. Caswell refused to surrender.

Caswell had built some defenses on the west side of the bridge. But these were not in a good spot. If they fought there, their only way to escape would be across the narrow bridge. MacDonald saw this problem in the plans. That night, the Loyalists decided to attack. They knew that if they waited to find another crossing, Moore's main army might arrive.

During the night, Caswell decided to move his men to the other side of the creek. To make it harder for the Loyalists, the Patriots removed the wooden planks from the bridge. They also greased the support rails, making them slippery.

The Battle Begins

By the time they reached Moore's Creek, the Loyalist force had shrunk to about 700 to 800 men. Most were Scottish Highlanders. Brigadier General MacDonald was sick, so he gave command to Lieutenant Colonel Donald MacLeod. The Loyalists left their camp at 1 AM on February 27 and marched to the bridge.

During the night, Caswell and his men built a curved dirt wall around their side of the bridge. They prepared to defend it with two small cannons.

The Loyalists arrived just before dawn. They found the defenses on the west side of the bridge empty. MacLeod told his men to hide behind nearby trees. But then a Patriot guard on the other side of the creek fired his musket to warn Caswell that the Loyalists were there. Hearing this, MacLeod immediately ordered his men to attack.

In the early morning mist, a group of Loyalist Highlanders approached the bridge. A Patriot guard called out, asking who they were. Captain Alexander Mclean said he was a friend of the King and shouted a challenge in Scottish Gaelic. When he heard no reply, he ordered his men to fire. This started a gunfight with the Patriot guards.

Lieutenant-Colonel MacLeod and Captain John Campbell then led a special group of swordsmen. They charged across the bridge, shouting in Gaelic, "King George and broadswords!"

When the Loyalists were very close to the dirt walls, the Patriot militia opened fire. The effect was terrible. MacLeod and Campbell were both hit by many bullets and fell. The Scottish Highlanders had only swords and faced many Patriot muskets and cannons. They had no choice but to retreat. The remaining men got back over the bridge, and the Loyalist force fell apart and ran away.

The Patriot forces quickly put the bridge planks back in place and chased after the fleeing Loyalists. One Patriot company even crossed the creek above the bridge, surrounding the retreating Loyalists. Colonel Moore arrived a few hours after the battle. He reported that about 30 Loyalists were killed or wounded. But he thought the total loss might be around 50, including those who fell into the creek. The Patriots reported only one killed and one wounded.

After the Battle

Over the next few days, the Patriot militia rounded up the Loyalists who had run away. About 850 men were captured. Most were released, but the leaders were sent to Philadelphia as prisoners. Even though there were strong feelings on both sides, the Loyalist prisoners were treated with respect. This helped convince many not to fight again.

Among those captured was a Scottish poet named Iain mac Mhurchaidh (John Macrae). His son, Murdo Macrae, also fought in the battle and was badly wounded.

The Patriots also captured the Loyalist camp at Cross Creek. They took 1,500 muskets, 300 rifles, and $15,000 in Spanish gold. Many of these weapons were probably hunting equipment. The victory made more people want to join the Patriot side. The arrests of many Loyalist leaders helped the Patriots take firm control of North Carolina. A newspaper at the time said, "This, we think, will effectually put a stop to loyalists in North Carolina."

The battle had a big impact on the Scottish Highlanders in North Carolina. Later in the war, many Loyalists refused to fight. Those who did were often driven from their homes by their Patriot neighbors.

When news of the battle reached London, people had different opinions. Some reports said the defeat wasn't a big deal because no regular British army troops were involved. Others noted that a smaller Patriot force had defeated the Loyalists. Lord George Germain, the British official in charge of the war, still believed Loyalists were a strong force, even after this defeat.

The British expedition that the Loyalists were supposed to meet was very delayed. It didn't leave Ireland until mid-February. Bad weather further delayed the ships. The full British force didn't arrive off Cape Fear until May 1776. As the British fleet gathered, North Carolina's Patriot leaders met. In early April, they passed the Halifax Resolves. This allowed North Carolina's representatives to vote for independence from the British Empire. The British General Clinton tried to attack Charleston, South Carolina, but he failed. This was the last major British attempt to control the southern colonies until late 1778.

Brigadier General Donald MacDonald was held as a prisoner of war in Philadelphia. It was hard to arrange a prisoner exchange for him. The British Army refused to accept his promotion to Brigadier General by Governor Martin. The Americans would only exchange him for a captured Patriot officer of the same rank.

Meanwhile, General MacDonald's son, also named Donald MacDonald, joined the Patriot side soon after his father was captured. This son was a brave and strong young Scotsman. He became a Sergeant and was known for his daring actions.

When asked why he joined "the rebels," Sergeant MacDonald explained that his father and his friends had been welcomed and helped by Americans after fleeing Scotland. He felt that when the British came to fight the Americans, his father and friends forgot all the kindness they had received. He believed God helped the Americans win because of this ingratitude. He said the Americans treated their prisoners kindly, unlike the British after a battle in Scotland. Because of this kindness, he loved the Americans and would fight for them.

Sergeant MacDonald was killed in action on May 12, 1781. His resting place is unknown, but his bravery is remembered.

After the battle, Flora MacDonald was questioned by the North Carolina Patriot leaders. She showed great courage. Later, she returned to Scotland. She faced many challenges, including breaking her arm during an attack by a French ship. Flora always said she served two different royal families and had bad luck with both. She died on March 5, 1790.

After the war, many areas in North Carolina settled by Scottish Highlanders became empty. Many Scottish Loyalists moved north to what remained of British North America (now Canada). However, a large Scottish Gaelic-speaking community continued to exist in North Carolina until the American Civil War.

Today, people in North Carolina are still very proud of their Scottish heritage. One of North America's largest Highland Games is held every year at Grandfather Mountain. It brings in visitors from all over the world. It is known for its beautiful scenery and the many people who attend in traditional Scottish kilts. It is also considered the largest "gathering of clans" in North America.

The Moore's Creek Bridge battlefield was saved in the late 1800s by private groups. The U.S. government took over the site in 1926. Today, the National Park Service manages it as the Moores Creek National Battlefield. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. The battle is remembered every year in late February.

Images for kids