Boston campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Boston campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill by John Trumbull |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,700–16,000 | 4,000–11,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 593 | 1,505 | ||||||

The Boston campaign was the first major part of the American Revolutionary War. It mostly happened in Massachusetts. This campaign started with the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. In these battles, local colonial militias stopped British soldiers from taking military supplies and capturing leaders in Concord, Massachusetts. The British soldiers faced many attacks as they marched back to Charlestown, losing many men.

After these battles, many colonial militia members gathered and surrounded the city of Boston. This started the siege of Boston. A big battle during this siege was the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. It was one of the bloodiest fights of the war. The British won, but they lost so many soldiers that it was like a defeat for them. There were also smaller fights near Boston and along the coast. These fights often resulted in losses of lives or supplies.

In July 1775, George Washington took charge of the colonial militias. He helped turn them into a more organized army. On March 4, 1776, the colonial army set up cannons on Dorchester Heights. These cannons could reach Boston and the British ships in the harbor. The siege and the campaign ended on March 17, 1776. On this day, British forces left Boston for good. Even today, Boston celebrates March 17 as Evacuation Day.

Contents

Why the War Started

In 1767, the British Parliament passed the Townshend Acts. These acts put taxes on things like paper, glass, and paint that were brought into the American colonies. Groups like the Sons of Liberty protested these new taxes. They organized boycotts, meaning people refused to buy the taxed goods. They also bothered the tax collectors.

Because of these protests, the Governor of Massachusetts, Francis Bernard, asked for British soldiers to protect the tax collectors. In October 1768, British troops arrived in Boston and took control of the city. This made tensions even higher. These tensions led to events like the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. Later, on December 16, 1773, colonists protested by dumping British tea into the harbor. This event is known as the Boston Tea Party.

To punish the colonies for the Tea Party, Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts. One of these acts, the Massachusetts Government Act of 1774, basically ended the local government in Massachusetts. General Thomas Gage, who was already the top British commander in North America, was also made governor of Massachusetts. His job was to make sure the King's rules were followed. However, most people in the countryside supported the Patriots. This meant royal officials often had to leave their posts or hide in Boston. General Gage had about 4,000 British soldiers in Boston, but the areas outside the city were mostly controlled by Patriot supporters.

War Begins

On September 1, 1774, British soldiers took gunpowder and other military supplies from a storage building near Boston. This surprise raid worried people in the countryside. Thousands of American Patriots quickly got ready, thinking war was about to start. This event was called the Powder Alarm. It turned out to be a false alarm, but it made everyone more careful. It was like a practice run for what would happen seven months later. After this, colonists started moving military supplies from forts in New England. They gave these supplies to local militias.

On the night of April 18, 1775, General Gage sent 700 soldiers to take ammunition stored by the colonial militia in Concord, Massachusetts. Riders like Paul Revere warned the countryside. When the British troops arrived in Lexington, Massachusetts on the morning of April 19, they found 77 minutemen waiting. Minutemen were special militia members ready to fight at a moment's notice. Shots were fired, and eight Minutemen were killed. The outnumbered colonial militia then scattered, and the British moved on to Concord.

In Concord, the British searched for military supplies. They found very little because the colonists had hidden most of them after being warned. During the search, there was a fight at the North Bridge. A small group of British soldiers fired on a larger group of colonial militia. The militia fired back and forced the British to retreat. By the time the "redcoats" (British soldiers) started marching back to Boston, thousands of militiamen had gathered along the road. A running battle followed, and the British lost many soldiers before reaching Charlestown. This day, with the Battle of Lexington and Concord, became known as the "shot heard 'round the world." The war had officially begun.

Siege of Boston

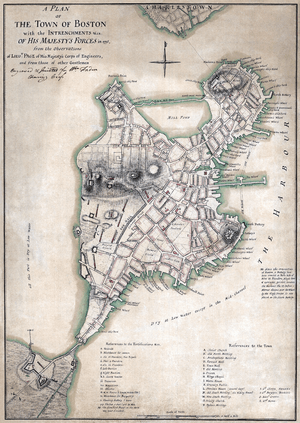

After the British failed to capture supplies in Concord, thousands of militiamen stayed around Boston. More arrived from places like New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. Under the command of Artemas Ward, they surrounded the city. This blocked all land routes into Boston, putting the city under siege. The British soldiers inside Boston built defenses on the high points of the city.

Getting Supplies

The British could get supplies by sea, but there wasn't enough food or other goods in Boston. British troops were sent to islands in Boston Harbor to take supplies from farmers. In response, the colonists started moving supplies off these islands so the British couldn't get them. In one fight, the Battle of Chelsea Creek, the British lost two soldiers and a ship called the Diana.

The British also needed building materials. Admiral Samuel Graves allowed a merchant who supported the British to send his ships from Boston to Machias, Maine. A British navy ship went with them. But the people of Machias fought back. They captured the merchant ships and then the navy ship after a short battle. This resistance, and similar actions by other towns along the coast, made Admiral Graves send a group to get revenge in October. Their main action was the Burning of Falmouth, where they burned down the town. This made the colonies very angry. It led the Second Continental Congress to create the Continental Navy, America's first navy.

The colonial army also had problems with supplies and leadership. Their different militias needed to be organized, fed, clothed, and armed. Also, each militia leader reported to their own province's government, which made it hard to coordinate.

Washington wanted to get back at the British for burning Falmouth. He also wanted to stop and capture British weapons heading to Boston. So, in October 1775, General Washington ordered the first American naval mission. He borrowed two ships from John Glover's Marblehead Regiment. Captain Nicholson Broughton commanded the Hancock and Captain John Selman (privateer) commanded the Franklin. Their trip north led to them capturing fishing boats near Canso, Nova Scotia and raiding Charlottetown.

Bunker Hill Battle

In late May, General Gage received about 2,000 more British soldiers by sea. Three important generals also arrived: William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton. They made a plan to break out of Boston. Reports of this plan reached the colonial commanders. They decided they needed to strengthen their defenses.

On the night of June 16–17, 1775, a group of colonial soldiers quietly marched onto the Charlestown peninsula. The British had left this area in April. The colonists built defenses on Bunker Hill and Breed's Hill. On June 17, British forces led by General Howe attacked. They captured the Charlestown peninsula in the Battle of Bunker Hill. The British technically won this battle. However, they lost about one-third of their attacking force, including many officers. This was such a heavy loss that they couldn't continue their attack. The siege of Boston was not broken. General Gage was called back to England in September, and General Howe took his place as the British commander.

Forming the Continental Army

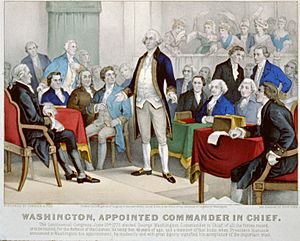

The Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in May 1775. They heard about the situation outside Boston. They also learned about the capture of Fort Ticonderoga on May 10. It became clear that a single, organized military was needed. On May 26, Congress officially recognized the forces outside Boston as the Continental Army. On June 15, they named George Washington its commander-in-chief. Washington left Philadelphia for Boston on June 21. He didn't find out about the Battle of Bunker Hill until he reached New York City.

Stalemate

After the Battle of Bunker Hill, the siege became a standstill. Neither side had a clear advantage. Neither side had the strength or supplies to make a big move. When Washington took command in July, he found that the army had shrunk from 20,000 to about 13,000 soldiers ready for duty. He also learned that the battle had used up most of the army's gunpowder. Luckily, more powder arrived from Philadelphia. The British were also getting more soldiers. By the time Washington arrived, the British had over 10,000 men in Boston.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1775, both sides dug in. There were small fights, but no major actions. Congress wanted to take the lead and use the captured cannons from Ticonderoga. They approved an invasion of Canada. In September, Benedict Arnold led 1,100 soldiers on a difficult trip through the wilderness of Maine. These soldiers came from the army outside Boston.

Washington faced a problem at the end of 1775. Many soldiers' enlistments were ending. He offered rewards to get people to join again. He managed to keep the army large enough to continue the siege, even though it was smaller than the British forces.

Siege Ends

By early March 1776, heavy cannons captured at Fort Ticonderoga had been moved to Boston. This was a very difficult task, planned by Henry Knox. When the cannons were placed on Dorchester Heights in just one day, they overlooked the British positions. This made the British position impossible to defend. General Howe planned an attack to take back the high ground, but a snowstorm stopped it.

The British then threatened to burn Boston if the Americans stopped them from leaving. On March 17, 1776, they evacuated the city. They sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, for safety. The local militias went home. In April, General Washington took most of the Continental Army to strengthen New York City. This started the New York and New Jersey campaign.

Legacy

The British were mostly driven out of New England because of this campaign. However, they still had supporters, called Loyalists, in places like Newport, Rhode Island. The Boston campaign, and the final result of the war, was a big blow to British pride and their military's confidence. The British military leaders from this campaign were criticized. For example, Clinton later commanded British forces in North America but was blamed for losing the war. Gage saw no more action, and Burgoyne was disgraced after surrendering his army at Saratoga.

Even though the British still controlled the seas and won battles in places like New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, their actions in Boston helped unite the Thirteen Colonies against the King. Because of this, they could never get enough support from Loyalists to truly control the colonies again.

The colonies, despite their differences, became united because of these events. They gave the Second Continental Congress (which is like today's U.S. Congress) enough power and money to fight the revolution as one group. This included funding and equipping the military forces that formed during the Boston campaign.

See also

In Spanish: Campaña de Boston para niños

In Spanish: Campaña de Boston para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |