Invasion of Quebec (1775) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Invasion of Quebec, 1775 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775 (John Trumbull, 1786) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 | 700–10,000+ | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400 killed, 650 wounded, 1,500 captured, 5,000 infected by smallpox |

100 killed, about 230 wounded, 600 captured |

||||||

The Invasion of Quebec was the first big military plan by the new Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. It happened between June 1775 and October 1776. The main goal was to take control of the Province of Quebec from Great Britain. The Americans also hoped to convince French-speaking Canadians to join their fight against the British.

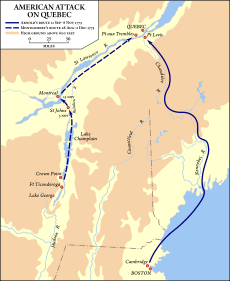

Two groups of American soldiers marched towards Quebec. One group, led by Richard Montgomery, captured Fort St. Johns and nearly caught British General Guy Carleton when they took Montreal. The other group, led by Benedict Arnold, faced a very tough journey through the wilderness of Maine to reach Quebec City. The two forces met near Quebec City, but they were defeated in the Battle of Quebec in December 1775.

Montgomery's group started from Fort Ticonderoga in late August. They began to attack Fort St. Johns in mid-September. This fort was a key defense point south of Montreal. After the fort fell in November, General Carleton left Montreal and escaped to Quebec City. Montgomery then took Montreal before heading to Quebec. His army was much smaller by then because many soldiers' enlistments had ended. He joined Arnold, whose journey through the wilderness had left his soldiers starving and without many supplies.

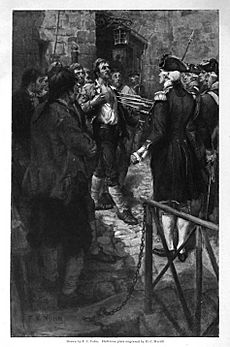

These American forces joined up outside Quebec City in December. They attacked the city during a snowstorm on the last day of the year. The battle was a terrible loss for the Continental Army. Montgomery was killed, and Arnold was wounded. The city's defenders had very few casualties. Arnold then tried to besiege the city, but it was not very effective. During this time, British supporters spread messages that made more people loyal to Britain. Also, General David Wooster's strict rule in Montreal upset both American supporters and those against them.

In May 1776, the British sent thousands of soldiers under General John Burgoyne to Quebec. These included Hessian mercenaries from Germany. General Carleton then launched a counter-attack. He pushed the American forces, who were weakened by smallpox and disorganization, all the way back to Fort Ticonderoga. The American army, led by Arnold, slowed the British advance enough. This meant the British could not attack Fort Ticonderoga in 1776. The end of this campaign set the stage for Burgoyne's 1777 campaign in the Hudson River valley.

Contents

Why it was called "Canada"

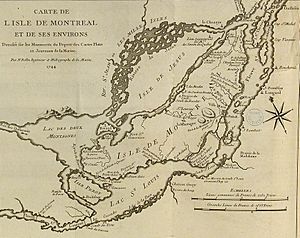

In 1775, the British province of Quebec was often called "Canada." For example, the Second Continental Congress told General Philip Schuyler to take control of "St. John's, Montreal, and any other parts of the Country" in "Canada."

Before 1763, much of this land was French Canada. France gave it to Britain in the Treaty of Paris (1763), which ended the French and Indian War. The name "Quebec" is used in this article to avoid confusion with the modern country of Canada.

How the War Started in Quebec

In the spring of 1775, the American Revolutionary War began with the Battle of Lexington and Concord. The British army was surrounded by colonial soldiers in Boston. In May 1775, Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen led colonial soldiers to capture Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point. They also raided Fort St. Johns. These forts were not well defended.

Congress Decides to Invade

The First Continental Congress had invited French-Canadians to join them in 1774. The Second Continental Congress sent another letter in May 1775, but got no real answer.

After capturing Ticonderoga, Arnold and Allen said that Quebec was poorly defended. They both suggested attacking Quebec. They thought a small force of 1,200 to 1,500 men could defeat the British there. Congress first ordered the forts to be left empty. But people in New England and New York protested.

When Congress learned that General Guy Carleton was making Fort St. Johns stronger and trying to get the Iroquois to join the British, they changed their minds. On June 27, 1775, Congress told General Philip Schuyler to plan an invasion if it seemed right. Benedict Arnold, who was not chosen to lead this mission, went to Boston. He convinced General George Washington to send a supporting force to Quebec City under his command.

British Get Ready for Defense

After the raid on Fort St. Johns, General Carleton knew an invasion was coming. He asked for more soldiers from General Thomas Gage in Boston, but did not get them right away. He tried to raise local militias to defend Montreal and Quebec City, but had little success.

Carleton sent 700 soldiers to hold Fort St. Johns on the Richelieu River. He also ordered boats to be built for Lake Champlain. He recruited about 100 Mohawk people to help defend the fort. Carleton himself oversaw Montreal's defense with only 150 regular soldiers. He relied on Fort St. Johns for the main defense. He left Quebec City's defense to Lieutenant-Governor Cramahé.

Montgomery's March to Quebec

General Schuyler was supposed to lead the main attack. He would go up Lake Champlain to Montreal, then to Quebec City. His army would be made of soldiers from New York, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. The Green Mountain Boys under Seth Warner would also join.

Moving Towards St. Johns

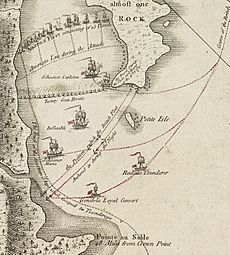

On August 25, Montgomery heard that British ships at Fort St. Johns were almost ready. Montgomery, while Schuyler was away, led 1,200 soldiers to Île aux Noix on the Richelieu River. They arrived on September 4. Schuyler, who was getting sick, joined them. The next day, they went to Fort St. Johns. After a small fight, they went back to Île aux Noix.

After this first fight, General Schuyler became too sick to continue. He gave command to Montgomery and left for Fort Ticonderoga. Montgomery then began to besiege Fort St. Johns on September 17. He cut off its supplies and communication with Montreal.

The next week, Ethan Allen was captured in the Battle of Longue-Pointe. He had tried to take Montreal with a small group of men, going against orders. This briefly made more local militias support the British. But many soon left again. After General Carleton failed to help the fort on October 30, it finally surrendered on November 3.

Taking Over Montreal

Montgomery then led his soldiers north. He occupied Saint Paul's Island in the Saint Lawrence River on November 8. He crossed to Pointe-Saint-Charles the next day, where people welcomed him. Montreal fell easily on November 13. Carleton decided the city could not be defended. Many of his militia soldiers had left after hearing about Fort St. Johns falling.

Carleton barely escaped capture. Some Americans had crossed the river downstream, and winds stopped his ships from leaving right away. He managed to sneak off his ship and made his way to Quebec City. On November 19, the British fleet surrendered. Among the captured was Moses Hazen, an American who had been treated badly by the British. Hazen joined Montgomery's army and later led the 2nd Canadian Regiment.

Before leaving Montreal for Quebec City, Montgomery told the people that Congress wanted Quebec to join them. He also talked with American supporters about holding a meeting to choose delegates for Congress.

Many of Montgomery's soldiers left after Montreal fell because their time in the army was up. He then used captured boats to move towards Quebec City with about 300 soldiers on November 28. He left about 200 men in Montreal under General David Wooster. Along the way, he picked up James Livingston's new 1st Canadian Regiment of about 200 men.

Arnold's Difficult Journey

Benedict Arnold had wanted to lead the Champlain Valley expedition but was not chosen. He went to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and suggested to George Washington a supporting attack on Quebec City from the east. Washington agreed. He gave Arnold 1,100 men, including Daniel Morgan's riflemen. Arnold's force sailed from Newburyport, Massachusetts, up the Kennebec River to Fort Western (now Augusta, Maine).

Arnold's journey was successful in that he brought soldiers to Quebec City. But the expedition faced problems as soon as it left settled areas in Maine. There were many hard portages (carrying boats over land) as they went up the Kennebec River. Their boats often leaked, ruining gunpowder and food. The land between the Kennebec and the Chaudière River was a swampy mess of lakes and streams. Bad weather made it even harder, and a quarter of the soldiers turned back. Going down the Chaudière, more boats and supplies were lost because the soldiers were not used to the fast water.

By the time Arnold reached the settled areas along the Saint Lawrence River in November, his force was down to 600 starving men. They had traveled almost 400 miles through wild land. When Arnold and his soldiers reached the Plains of Abraham on November 14, Arnold sent someone to demand the city's surrender, but it did not work. The Americans had no cannons and were barely fit to fight against a fortified city. Arnold decided on November 19 to pull back to Pointe-aux-Trembles. He waited for Montgomery, who had just captured Montreal. As Arnold went upriver, Carleton returned to Quebec by river after his defeat in Montreal.

On December 2, Montgomery finally came down the river from Montreal with 500 soldiers. He brought captured British supplies and winter clothes. The two forces joined, and they planned an attack on the city. Three days later, the Continental Army was again on the Plains of Abraham and began to besiege Quebec City.

Battle and Siege of Quebec

While planning the attack, Christophe Pélissier, a Frenchman who supported the Americans, met with Montgomery. Pélissier ran an ironworks and agreed to make ammunition for the siege.

Montgomery, Arnold, and James Livingston attacked Quebec City during a snowstorm on December 31, 1775. The Americans were outnumbered and had no real advantage. Carleton's forces easily defeated them. Montgomery was killed, Arnold was wounded, and many men were captured, including Daniel Morgan. After the battle, Arnold sent messengers to Montreal and Congress to report the defeat and ask for help.

Carleton chose not to chase the Americans. He stayed inside the city's defenses and waited for more soldiers to arrive when the river thawed in spring. Arnold kept up a weak siege of the city until March 1776. Then, he was ordered to Montreal and replaced by General Wooster. During these months, the American army suffered from the harsh winter. Smallpox also spread quickly through the camp. Even though small groups of new soldiers arrived each month, many were sick.

Congress had approved sending up to 6,500 more soldiers to Quebec even before they heard about the defeat. Throughout the winter, soldiers slowly arrived in Montreal and the camp outside Quebec City. By the end of March, the army besieging Quebec had almost 3,000 men. But nearly a quarter of them were too sick to fight, mostly from smallpox.

Problems in Montreal

When General Montgomery left Montreal for Quebec City, he put Brigadier General David Wooster in charge. At first, Wooster had good relations with the people. But he started doing things that made the local population dislike the American soldiers. He arrested British supporters and threatened anyone against the American cause. He also took away weapons from some towns. He tried to force local militia members to give up their British military positions. Those who refused were arrested. These actions, along with the Americans paying for supplies with paper money instead of coins, made people lose faith in the American effort. On March 20, Wooster left to command the forces at Quebec City. Moses Hazen was left in charge of Montreal until Arnold arrived on April 19.

On April 29, a group from the Second Continental Congress arrived in Montreal. This group included Benjamin Franklin. They were supposed to check on the situation and try to get people to support the American cause. But they were not very successful because relations were already bad. They had not brought any real money to pay for supplies. Their efforts to get Catholic priests to support them also failed. The priests said the Quebec Act from the British Parliament had already given them what they wanted. Franklin left Montreal on May 11 after hearing that the American forces at Quebec City were retreating in a panic.

The Cedars and Quinze-Chênes

Upriver from Montreal, there were small British army posts. As spring came, groups of Cayuga, Seneca, and Mississauga warriors gathered at Oswegatchie. This gave Captain George Forster, the British commander there, a force to cause trouble for the Americans.

To stop supplies from reaching the British upriver, Moses Hazen sent Colonel Timothy Bedel and 390 men to Les Cèdres. They built defenses there. On May 15, Colonel Forster moved downriver with about 250 Native Americans, militia, and regular soldiers. In a strange series of fights called the Battle of the Cedars, Bedel's officer, Isaac Butterfield, surrendered his entire force without a fight on May 18. Another 100 American reinforcements also surrendered after a short fight on May 19.

When Arnold heard about this, he quickly gathered soldiers to get them back. He dug in at Lachine, near Montreal. Forster moved closer to Montreal with about 500 men. But on May 24, he learned that Arnold was expecting more soldiers who would greatly outnumber him. Forster's force was shrinking. He agreed to exchange his American prisoners for British prisoners taken at Fort St. Johns. After a brief cannon fight at Quinze-Chênes, Arnold also agreed to the exchange. It happened between May 27 and 30.

British Reinforcements Arrive

American Soldiers Arrive

General John Thomas could not move north until late April because Lake Champlain was still frozen. He asked Washington for more men. When he arrived in Montreal, he found that many soldiers had promised to stay only until April 15 and wanted to go home. This was made worse by low numbers of soldiers joining regiments for Quebec. One regiment that was supposed to have 750 men sailed north with only 75.

Congress then told Washington to send more soldiers north. In late April, Washington ordered ten regiments, led by Generals William Thompson and John Sullivan, to go north from New York. This greatly reduced Washington's forces. There were also problems transporting these men and supplies across Lakes George and Champlain. As a result, Sullivan's men were delayed at Ticonderoga. Sullivan did not reach Sorel until early June.

General Wooster arrived at the American camp outside Quebec City in early April with more soldiers. More small groups of soldiers kept arriving from the south. By the end of April, General Thomas arrived and took command. His force was supposed to be over 2,000 strong, but many were sick from smallpox or the hard winter. On May 2, rumors started that British ships were coming up the river. Thomas decided on May 5 to move the sick to Trois-Rivières. The rest of the forces would leave as soon as possible. Later that day, he heard that 15 ships were waiting to come up the river. The next morning, ship masts were seen. The wind had changed, and three British ships had reached the city.

British Soldiers Arrive

After news of the battles at Lexington and Concord reached London, the British government realized it needed foreign soldiers to fight the rebellion. They tried to get Russian soldiers, but were refused. However, several German states agreed to send their troops. Of the 50,000 soldiers Britain raised in 1776, almost one-third came from these German states. The soldiers from Hesse-Cassel and Hesse-Hanau were often called Hessians. About 11,000 of these soldiers were sent to Quebec.

Carleton quickly unloaded soldiers from the arriving ships. Around noon, he marched with about 900 soldiers to test the Americans. The Americans panicked and began a disorganized retreat. It could have been worse for them if Carleton had pushed harder. He hoped to win over the rebels by being kind. He sent ships up the river to bother the Americans and try to cut them off. He also captured many Americans, mostly sick and wounded. The Americans left behind valuable military items, like cannons and gunpowder, in their rush to leave.

They regrouped on May 7 at Deschambault, about 40 miles upriver from Quebec City. Thomas held a meeting where most leaders wanted to retreat. Thomas decided to keep 500 men at Deschambault and send the rest to Sorel. He also sent word to Montreal for help, as many soldiers had little more than their clothes and a few days' food.

The Congress group in Montreal decided that holding the Saint Lawrence River was no longer possible. They sent only a few soldiers towards Deschambault. Thomas waited six days for news from Montreal, but heard nothing. He began to retreat towards Trois-Rivières. He had to fight off British soldiers who landed from ships on the river. They reached Trois-Rivières on May 15. There, they left the sick and some New Jersey soldiers to defend them. By May 18, the remaining soldiers joined new troops under General Thompson at Sorel. On May 21, a meeting was held with the Congress delegates. Thomas caught smallpox that same day and died on June 2. Thompson replaced him.

Carleton's Counter-Attack

Trois-Rivières Battle

On May 6, 1776, British ships arrived to help Quebec with supplies and 3,000 soldiers. This caused the Americans to retreat to Sorel. However, General Carleton did not make a big attack until May 22. He sailed to Trois-Rivières with two regiments. He heard about Forster's success at Les Cèdres. But instead of pushing forward, he returned to Quebec City. He left Allen Maclean in command at Trois-Rivières. There, he met Lieutenant General John Burgoyne, who arrived on June 1 with a large force of mostly Irish soldiers, Hessian allies, and a lot of money.

The Americans at Sorel heard that there were "only 300 men" at Trois-Rivières. They thought they could send a force to take it back. General Thompson led 2,000 men first into a swamp. Then, they marched into a strong British army that was dug in. This was a disaster. Thompson and many of his officers were captured, along with 200 men and most of the ships. This battle showed the end of the American control of Quebec. The American forces at Sorel, now led by General Sullivan, retreated. Carleton again did not push his advantage. He even sent the captured Americans back to New York in comfort in August.

Retreat to Crown Point

Early on June 14, Carleton finally sailed his army up the river to Sorel. They arrived late in the day and found that the Americans had left Sorel that morning. They were retreating up the Richelieu River valley towards Chambly and St. Johns. Unlike their hurried departure from Quebec City, the Americans left in a more organized way. However, some units were separated by Carleton's fleet and had to march to Montreal to join Arnold's forces. Carleton sent General Burgoyne and 4,000 soldiers up the Richelieu after the Americans. Carleton continued sailing towards Montreal.

In Montreal, Arnold did not know what was happening downriver. A messenger he sent on June 15 saw Carleton's fleet. He escaped to shore and returned to Montreal with the news on a stolen horse. Within four hours, Arnold and the American soldiers around Montreal had left the city. They tried to burn it down before leaving. Carleton's fleet arrived in Montreal on June 17.

Arnold's soldiers caught up with the main army near St. Johns on June 17. Sullivan's army was not ready to fight. After a short meeting, they decided to retreat to Crown Point. The army reportedly left St. Johns just moments before Burgoyne's army arrived.

The remains of the American army arrived at Crown Point in early July. This ended a campaign that one doctor called "a strange mix of the most unusual and unmatched problems and suffering." But the campaign was not quite over, as the British were still moving.

Building Ships and Politics

The Americans had been careful during their retreat to destroy or sink any boats they did not take with them. This forced the British to spend several months building ships. General Arnold had created a small navy when he captured Fort Ticonderoga. This navy was still patrolling Lake Champlain.

While the British built their navy, Carleton dealt with issues in Montreal. He set up groups to find out who had supported the Americans. These groups arrested people who had actively helped the American cause. When he arrived in Montreal, similar groups were formed.

Valcour Island Battle

General Horatio Gates took command of the Continental Army's northern forces in early July. He moved most of the army to Ticonderoga. He left about 300 men at Crown Point. The army worked on improving defenses at Ticonderoga. Arnold was given the job of building up the American fleet at Crown Point. Throughout the summer, more soldiers arrived at Ticonderoga. The army was estimated to be 10,000 strong. Shipbuilders worked hard at Skenesborough (now Whitehall) to build ships to defend the lake.

Carleton began to move on October 7. By October 9, the British fleet was on Lake Champlain. In a naval battle between Valcour Island and the western shore, starting on October 11, the British heavily damaged Arnold's fleet. Arnold had to retreat to Crown Point. He felt Crown Point would not be safe from a strong British attack, so he retreated to Ticonderoga. British forces occupied Crown Point on October 17.

Carleton's soldiers stayed at Crown Point for two weeks. Some soldiers went within three miles of Ticonderoga, trying to get Gates' army to come out and fight. On November 2, they left Crown Point and went to winter quarters in Quebec.

What Happened Next

The invasion of Quebec was a disaster for the Americans. But Arnold's actions during the retreat and with his makeshift navy on Lake Champlain were praised. They delayed a full British attack until 1777. Many reasons were given for the invasion's failure, including the high number of smallpox cases among American soldiers.

Carleton was criticized for not chasing the Americans more aggressively. Because of this criticism and because Carleton was disliked by Lord George Germain, the British official in charge of the war, command of the 1777 attack was given to General Burgoyne instead. This made Carleton resign as Governor of Quebec.

Many Continental soldiers at Fort Ticonderoga were sent south in November. They helped Washington's struggling defense of New Jersey. Conquering Quebec remained a goal for Congress throughout the war. However, George Washington thought any more attacks on Quebec would take too many soldiers and supplies away from the main war. So, no more large attacks on Quebec happened.

Hundreds of men of British and French descent continued to serve in the Continental Army after 1776. They fought in different parts of the war, including the siege of Yorktown. Many could not get back their property in Quebec. They stayed in the army out of need and kept asking American leaders for the money they were promised. After the war, some of these Canadians settled in a special area in northern New York.

During the peace talks in Paris, American negotiators tried to get all of Quebec as part of the war spoils. Benjamin Franklin suggested Quebec should be given to America. But only the Ohio Country, which had been part of Quebec, was given to the Americans.

In the War of 1812, the Americans tried another invasion of British North America. Again, they expected the local people to support them. That invasion also failed. It is now seen as a very important event in Canadian history. Some even say it was the birth of modern Canadian identity.

See also

In Spanish: Invasión de Canadá (1775) para niños

In Spanish: Invasión de Canadá (1775) para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |