Richard Montgomery facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Montgomery

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 2 December 1738 Swords, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 31 December 1775 (aged 37) Quebec City, Province of Quebec, British America |

| Buried |

Quebec City, Province of Quebec, British America

(reinterred in 1818 to St. Paul's Churchyard, Manhattan, New York City) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Rank | Major general |

| Battles/wars | |

| Signature | |

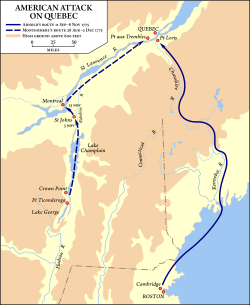

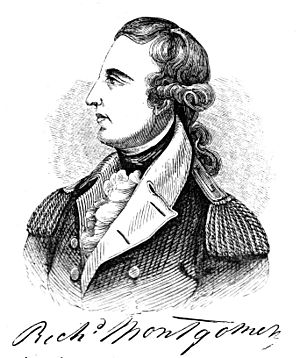

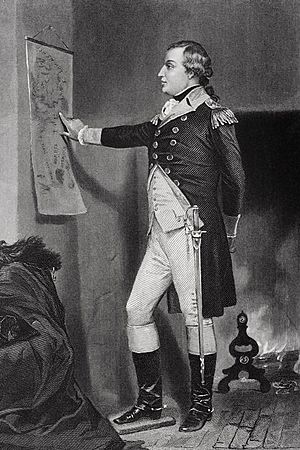

Richard Montgomery (born December 2, 1738 – died December 31, 1775) was an Irish soldier. He first served in the British Army. Later, he became a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He is best known for leading the 1775 invasion of Quebec, which was not successful.

Montgomery was born and grew up in Ireland. In 1754, he went to Trinity College, Dublin. Two years later, he joined the British Army to fight in the French and Indian War. He moved up in rank, serving in North America and then the Caribbean. After the war, he was at Fort Detroit during Pontiac's War. He then returned to Britain because of his health. In 1773, Montgomery came back to the Thirteen Colonies. He married Janet Livingston and started farming.

When the American Revolutionary War began, Montgomery supported the Patriot side. He was chosen for the New York Provincial Congress in May 1775. In June 1775, he became a brigadier general in the Continental Army. When Philip Schuyler became too sick to lead the invasion of Canada, Montgomery took over. He captured Fort St. Johns and then Montreal in November 1775. He then moved to Quebec City, where he met up with another army led by Benedict Arnold. On December 31, he led an attack on the city. He was killed during the battle. The British found his body and buried him with respect. His remains were moved to New York City in 1818.

Contents

Early Life and Military Start

Richard Montgomery was born near Swords in Ireland. His family was wealthy and had a history of military service. His father, Thomas Montgomery, was a British Army officer and a member of the Irish Parliament.

Richard spent most of his childhood at Abbeville House. There, he learned skills like hunting, riding, and shooting. His father made sure he got a good education. Richard learned French, Latin, and public speaking. He went to Trinity College, Dublin in 1754.

Even though he loved learning, Montgomery did not finish his degree. His father and older brother wanted him to join the military. So, on September 21, 1756, his father bought him a position as an ensign. He joined the 17th Regiment of Foot.

Seven Years' War Service

Fighting in North America

In 1757, Montgomery's unit, the 17th Foot, sailed from Ireland to Halifax, Nova Scotia. They were preparing for a planned attack on Louisbourg. This attack was called off, and they spent the winter in New York. In 1758, they returned to Halifax to try again to capture Louisbourg.

British generals Jeffery Amherst and James Abercromby planned the attack on Louisbourg. The French had only 800 soldiers, while the British had over 13,000 troops and many warships. On June 8, 1758, the attack began. Montgomery landed on the beach under heavy fire. He ordered his soldiers to charge with their bayonets. The French defenses fell back. Montgomery's unit chased them close to the fort. The British then prepared to surround the city. After weeks of bad weather, the French surrendered on July 26. General Amherst was impressed and promoted Montgomery to lieutenant.

Later, in 1759, Montgomery and the 17th Foot helped capture Fort Carillon (also known as Fort Ticonderoga). This was part of a larger plan to invade Canada. Montgomery's company was on guard duty before the battle. He warned his men to watch out for French and Native American ambushes. His suspicions were correct when 12 of his men were attacked. On July 21, the army moved towards Fort Carillon. The French had already left most of their forces. They blew up the fort's powder storage and retreated.

In 1760, Montgomery was promoted to regimental adjutant. This was a special position given to a promising lieutenant. In August, the 17th Foot joined other British forces for a three-part attack on Montreal. They captured Île aux Noix and Fort Chambly. They then met the other armies outside Montreal. The French governor of Canada, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, surrendered the city without a fight. With Montreal captured, all of Canada came under British control.

Fighting in the Caribbean

After taking Canada, the British planned to defeat the French in the West Indies. In November 1761, Montgomery and the 17th Foot sailed to Barbados. They joined other units there. On January 5, 1762, they left for the French island of Martinique. The French had strong defenses, but the British quickly landed. The main attack began on January 24. The French outer defenses were taken, and the survivors fled to the capital, Fort Royal. The British prepared to attack the fort, but the French surrendered. By February 12, the entire island had surrendered. After Martinique fell, other French islands like Grenada, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent also surrendered easily. On May 6, 1762, Montgomery was promoted to captain for his actions in Martinique.

Spain joined the war in 1761 as France's ally. The British decided to capture Havana in Cuba. This would cut off Spain's communication with its colonies. On June 6, British forces arrived near Havana. Montgomery's company was part of the 17th Foot, which was tasked with capturing Moro Fort. This fort was key to Havana's defense. British warships bombed the fort. On July 30, Montgomery and the 17th Foot stormed and captured the fort. In late August 1762, Montgomery and his unit were sent to New York. They stayed there until the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763.

Pontiac's War

Pontiac's War began in April 1763. Ottawa chief Pontiac organized 18 Native American tribes. They were angry about the French surrender and British policies. They attacked British military and civilian settlements. General Amherst sent the 17th Foot to Albany to help.

On the way to Albany, Montgomery's ship got stuck near Clermont Manor. This was the home of the powerful Livingston family. While the ship was being freed, Montgomery met Janet Livingston, who was 20 years old.

The 17th Foot was first stationed at Fort Stanwix. Montgomery stayed there until 1764. He then asked for leave to return to England because his health was suffering from his time in the Caribbean. His request was granted.

In 1764, the British organized two expeditions to fight the uprising. Montgomery and the 17th were part of one expedition that went to Fort Niagara in July. They stayed there for a month while Sir William Johnson held a large meeting with Native Americans. They then marched to Fort Detroit, which had been attacked earlier. Montgomery helped improve the fort's defenses and learned about interacting with Native Americans. In September, Montgomery, whose leave had been approved, traveled to New York. He delivered messages to General Gage before sailing for England.

Life in Britain and Return to America

In Britain, Montgomery recovered his health. He became friends with Whig politicians like Edmund Burke. These politicians generally supported the American colonists. Montgomery discussed politics with them and began to question the British government's actions.

In 1771, he was not promoted, possibly because of his political views. So, in 1772, he sold his military position and left the army. He bought scientific and surveying tools. He sailed to America in July 1772, planning to become a farmer.

Settling in New York

Montgomery bought a farm at King's Bridge, north of New York City. He reconnected with Janet Livingston. They married on July 24, 1773. Through this marriage, Montgomery became a slave owner, as the Livingstons were a prominent family who owned slaves in the region.

After their marriage, Montgomery leased his farm to someone else. Janet's grandfather gave them a small house in Rhinebeck. Montgomery bought more land and started farming. He built fences, plowed fields, and planned a larger home. He said he was "Never so happy in all my life," but also felt it "cannot last."

Because Montgomery was now connected to the powerful Livingston family, who supported the Patriot cause, he began to oppose the British government. He started to see himself as an American, not an Englishman. He believed the British government was acting like a harsh parent.

New York Provincial Congress

On May 16, 1775, Montgomery was chosen to represent Dutchess County in the New York Provincial Congress. Even though he had only lived in New York for two years, he was well-known and respected. He felt he had to go to the Congress in New York City.

The Congress began on May 22. Montgomery and 96 other delegates signed a paper giving the Congress its authority. Montgomery was a moderate Patriot. He thought the British government was wrong but hoped for a peaceful solution. He helped choose locations for military defenses in New York. He also helped organize the local army and get supplies.

American Revolution Role

Becoming a General

On June 15, 1775, George Washington became Commander-in-Chief of the new Continental Army. The Second Continental Congress asked New York to choose two generals. One would be a major general, and the other a brigadier general. The assembly chose Philip Schuyler as major general. Montgomery worried that Schuyler did not have enough combat experience. Even though Montgomery was considered for brigadier general, he did not openly seek the position. Still, Schuyler became major general, and Montgomery became brigadier general on June 22. Montgomery was ranked second among all brigadier generals.

About his new role, he said, "The Congress having done me the honor of electing me brigadier-general in their service, is an event which must put an end, for awhile, perhaps for ever, to the quiet scheme of life I had prescribed for myself; for, though entirely unexpected and undesired by me, the will of an oppressed people, compelled to choose between liberty and slavery, must be obeyed."

Planning the Invasion of Quebec

On June 25, George Washington passed through New York City. Washington made Montgomery Schuyler's deputy commander. A few days later, Schuyler received orders to invade Canada. The plan was to invade Quebec using the Hudson River and northern lakes for supplies. An army quickly gathered at Fort Ticonderoga. Schuyler left to command the army on July 4. Montgomery stayed in Albany to finish invasion plans. His wife went with him as far as Saratoga. He told her, "You shall never have cause to blush for your Montgomery."

Through July and early August, Montgomery and Schuyler organized their forces. They gathered men and supplies for the invasion. Washington decided to expand the invasion. He ordered Benedict Arnold to lead another force to invade Quebec from Maine. This force would meet Schuyler's army outside Quebec City for a joint attack.

Invasion of Quebec Begins

In August, Schuyler left to meet with the Iroquois Confederacy to keep them neutral. Montgomery was left in command at Fort Ticonderoga. While Schuyler was away, Montgomery learned that the British were building gunboats on Lake Champlain. These boats would give the British control of the lake. Without asking Schuyler, Montgomery moved 1,200 men north on two ships. He wrote to Schuyler explaining his actions.

Schuyler returned to Fort Ticonderoga on August 30. He sent 800 more men to Montgomery. Despite being ill, Schuyler joined Montgomery on September 4. He took command and ordered the army to continue to Île aux Noix, an island in the Richelieu River. Schuyler, still unwell, wrote a message to Canadians. He called them "Friends and Countrymen" and asked for their help to remove the British from Canada.

On September 6, Montgomery led a small force to Fort St. Johns. This fort was key to the British defense of Montreal. Montgomery led the main army through a swampy, wooded area. A group led by Captain Matthew Mead was ambushed by 100 Native Americans allied with the British. They held their ground, forcing the attackers back to the fort. Montgomery feared the British force was larger than he thought. He stopped operations for the day and pulled his men back. Believing the fort could not be captured quickly, Schuyler called Montgomery's force back to Île aux Noix.

Schuyler's health worsened, so Montgomery took over daily command. On September 10, a larger force of 1,700 men led by Montgomery moved towards the fort. In the swampy area, it was so dark that two American groups ran into each other. Each thought the other was British and fled. Montgomery stopped them. As they advanced, they came under British grapeshot fire. One American group attacked British defenses but fell back. The next morning, Montgomery called a meeting. They agreed to attack the fort again. However, news spread that a British warship was coming, and half the New England troops fled. Montgomery, angry, believed his force could no longer take the fort. He retreated back to Île aux Noix. Montgomery asked Schuyler to hold a court-martial for the fleeing troops. Schuyler's health did not improve. He left for Ticonderoga on September 16 to recover, giving Montgomery full control.

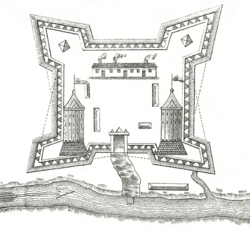

Siege of St. Johns

Outside Fort Saint-Jean (Quebec), Montgomery kept getting more soldiers. He removed commanders he felt were not good enough. He said, "I hope we shall have none left but fighting men on whom I can rely."

On September 16, Montgomery organized another attack on the British fort. He had 1,400 men. He sent a naval group with ships and boats to fight any move by the British warship, Royal Savage. Montgomery took the rest of his force and sailed up the river, landing near St. Johns on September 17. The British fort had 725 men, led by Major Charles Preston. Preston had been Montgomery's superior officer just three years earlier.

Montgomery and his troops spent the first night near the landing area, under light fire from British guns. The next morning, he ordered Major Timothy Bedel to take a position north of the fort. But when Montgomery saw his men were nervous, he led the mission himself. As Montgomery led his troops, they found a fight between British soldiers and another American group. Montgomery took command and forced the British back into the fort. Montgomery then placed other troops around the fort and began a siege.

Preston and the British had many more guns and ammunition than the Americans. For the first few weeks, they had a 10-to-1 advantage in firepower. Montgomery focused on improving the siege works. Within days, they built two batteries (groups of cannons) under constant fire from the fort. On September 22, Montgomery was almost killed while checking the defenses. A cannonball shot past him, tearing his coat and knocking him off the wall. But he landed on his feet. The soldiers saw that this "did not seem to hurt or frighten him."

The Americans kept getting weapons from Ticonderoga. New guns arrived on September 21 and October 5. However, the cannons were too far away to do much damage. With the new guns, Montgomery wanted to move the bombing closer to the north side of the fort. But his officers disagreed. They feared many men would leave because of the increased danger. Montgomery ordered a new battery built where the Royal Savage could be attacked. On October 14, the battery was finished and used to sink the British ship.

In mid-October, James Livingston, an American living near Chambly, suggested attacking Fort Chambly. It was about 10 miles downstream and weaker than St. Jean. Montgomery liked the idea and sent 350 men to take Chambly. On the night of October 16, two American cannons were secretly moved past Fort St. Jean towards Chambly. The next morning, these cannons fired on Chambly. After two days, holes were made in the fort's walls. The British commander surrendered the fort. The Americans captured 6 tons of gunpowder and 83 men. Montgomery sent the flags of the 7th Royal Fusiliers, who had defended the fort, to Schuyler. These were the first flags of a British regiment captured in the war. Washington sent Montgomery a letter of congratulations.

Capturing Chambly made Montgomery's army feel much better. He then went ahead with his plan to build a battery north of Fort St. Jean, this time without opposition. While the Americans built the batteries, the British heavily bombed them, but few Americans were hurt. General Guy Carleton, leading the British forces at Montreal, knew the situation at Fort St. Jean was bad. He personally led a relief force in late October. But American forces stopped it from crossing the Saint Lawrence River.

On November 1, the new batteries north of the fort were ready. The Americans began firing at the fort and continued all day. The British fired back, but were less effective. The American guns caused few deaths but heavily damaged the inside of the fort. The soldiers inside the fort lost hope as the bombing and lack of food continued. At sunset, Montgomery stopped the firing. He sent a prisoner captured at Chambly into the fort with a letter asking for surrender. A messenger from Carleton to Preston was captured that night. Carleton's message ordered Preston to keep fighting. On November 2, the British agreed to surrender with full military honors. They marched out of the fort on November 3 and were sent to the colonies. The British had 20 killed and 23 wounded. The Americans had only five killed and six wounded during the whole siege.

From Montreal to Quebec

Montgomery then turned his army towards Montreal. The march was hard because of snow, water, and ice. A winter storm hit a few days after they left. To stop British troops from escaping Montreal to Quebec, Montgomery sent a group to Sorel. This group briefly fought with British troops. The British quickly went back to their ships in the St. Lawrence River. When Montgomery and the main army reached Montreal, Montgomery sent a message demanding the city's surrender. He threatened bombardment if they refused. While they talked about surrender, Carleton escaped down the St. Lawrence River in small ships. The city surrendered on November 13. Montgomery and his army marched into the city without a fight.

On November 19, the British ships were captured. But Carleton barely escaped and made his way to Quebec City. Montgomery's kind treatment of the captured British prisoners worried some American officers. Montgomery saw this as a challenge to his authority. This, along with the lack of discipline in the army, made Montgomery threaten to resign. Letters from Washington, who also had problems with troop discipline, convinced Montgomery to continue his command.

On November 28, Montgomery and 300 men boarded some captured ships. They sailed to Quebec City. On December 2, Montgomery joined Benedict Arnold's force at Pointe aux Trembles, 18 miles from Quebec. Arnold gave command of his forces to Montgomery. On December 3, Montgomery gave Arnold's men, who had marched through the Maine wilderness and suffered greatly, much-needed supplies. These included clothing and winter gear from the captured British ships. The next day, the army moved towards the city. When they arrived, Montgomery ordered the city to be surrounded. On December 7, Montgomery sent a message to Carleton, demanding the city's surrender. Carleton burned the letter. Days later, Montgomery sent another letter into the city, telling merchants that they had come to free Quebec's civilians. However, Carleton found out and arrested the messenger. Montgomery then used bows and arrows to shoot the message over the wall.

Attack and Death

Montgomery did not know that he had been promoted to major general on December 9 for his victories at St. Johns and Montreal. After he failed to convince Carleton to surrender, Montgomery placed several mortars a few hundred yards outside the city walls. The bombing of the city began on December 9. But after several days, it had not seriously damaged the walls, the soldiers, or the civilians. Since the bombing had little effect, Montgomery ordered another battery to be placed closer to the city walls, on the Plains of Abraham. This area offered little natural cover from enemy fire. On December 15, the new batteries were ready. Montgomery sent a group of men with a white flag to ask for the city's surrender. But they were turned away. Montgomery then continued firing on the city, but it had little effect. When the new batteries were hit by more accurate British fire, Montgomery ordered them to be evacuated.

Since bombing the city was not working, Montgomery began to plan an attack. Montgomery would attack the Lower Town district (Saint-Roch), near the river. Arnold would attack and take the Cape Diamond Bastion, a strong part of the city walls on the highest point of the rocky hill. Montgomery believed they should attack during a stormy night so the British could not see them. On December 27, the weather became stormy, and Montgomery ordered his men to prepare. However, the storm soon stopped, and Montgomery called off the attack. As Montgomery waited for a storm, he had to change his plans. A soldier who left the American side told the British the original plan. In the new plan, Montgomery would attack the Lower Town from the south. Arnold would attack the Lower Town from the north. After breaking through the walls, Montgomery and Arnold would meet in the city. Then they would attack and take the Upper Town, causing the British to give up. To surprise the British, Montgomery planned two fake attacks. One group of soldiers would set fire to a gate. Another group would fight the guards at Cape Diamond Bastion and fire rockets to signal the start of the attack. While these fake attacks happened, cannons would fire into the city. Montgomery did not want to attack, but Arnold's soldiers' enlistments were ending on January 1. Montgomery was worried about losing them.

On the night of December 30, a snowstorm hit. Montgomery gave the order to attack. The Americans began to move to their positions. At 4:00 AM, Montgomery saw the rocket flares. He began to move his men around the city towards the Lower Town. The rockets were meant to signal the attack, but they also warned the British. The city's defenders rushed to their posts. Montgomery personally led the march to the Lower Town. They went down the steep, slippery cliffs outside the city walls. At 6:00 AM, Montgomery's force reached a wooden fence at the edge of the Lower Town. They had to saw through it. After sawing through a second fence, Montgomery led the first group through the opening. He saw a two-story blockhouse down the street. Montgomery led the troops towards it, encouraging them by drawing his sword and shouting, "Come on, my good soldiers, your General calls upon you to come on." When the Americans were about 50 yards away, the British soldiers in the blockhouse (30 Canadian militia and some sailors) opened fire with cannons, muskets, and grapeshot. Montgomery was killed by grapeshot through the head and both thighs. Captains John Macpherson and Jacob Cheesman were also killed.

With Montgomery's death, his attack failed. Colonel Donald Campbell, the next highest officer, ordered a panicked retreat. One of Montgomery's officers, Aaron Burr, tried to drag his commander's body to safety. But the snow and Montgomery's weight made it impossible. Without Montgomery's help, Arnold's attack, after some early success, also failed. Arnold was wounded in the leg, and many of his soldiers were captured, including Daniel Morgan.

Funeral and Mourning

On January 1, 1776, the British began collecting bodies. They soon found the body of a high-ranking American officer. An American prisoner confirmed it was Richard Montgomery.

After Montgomery's death was announced, Benedict Arnold took command of the American forces. Montgomery was respected by both sides. Carleton ordered that he be buried with dignity, but without too much ceremony. At sunset on January 4, 1776, Montgomery's remains were buried. During his burial, American prisoners called Montgomery a "beloved general" with "heroic bravery" who had the "confidence of the whole army."

Schuyler and Washington were very sad to hear of Montgomery's death. Schuyler believed that without Montgomery, victory in Canada was not possible. He wrote to Congress and Washington, "My amiable friend, the gallant Montgomery, is no more; the brave Arnold is wounded; and we have met a severe check, in an unsuccessful attempt on Quebec." Washington wrote, "In the death of this gentleman, America has sustained a heavy loss." Congress tried to keep the news quiet. They feared it would lower the morale of the troops and civilians.

On January 25, 1776, Congress approved building a monument to Montgomery. A memorial service was held on February 19, 1776. Across the thirteen colonies, Montgomery was seen as a hero. Patriots used his death to promote their cause in the war. Writers like Thomas Paine often mentioned Montgomery. The poet Ann Eliza Bleecker wrote a poem in his memory.

Montgomery was also mourned in Britain. British politicians who supported the colonists used his death to show that British policies were failing. Prime Minister Lord North recognized Montgomery's military skill. But he said, "I cannot join in lamenting the death of Montgomery as a public loss. Curse on his virtues! They've undone his country. He was brave, he was able, he was humane, he was generous, but still, he was only a brave, able, humane, and generous rebel." London newspapers paid tribute to Montgomery. The Evening Post bordered its March 12 edition in black as a sign of mourning.

Aftermath and Legacy

Janet, Montgomery's wife, lived for 53 years after his death. She always called him "my general" or "my soldier" and protected his good name. After he died, Janet moved to the house near Rhinebeck that Montgomery had started building before the war. Janet remained interested in politics and was a strong critic of those loyal to the King. After the war, former Continental Army general Horatio Gates asked her to marry him, but she said no.

In 1818, Stephen van Rensselaer, the Governor of New York, got permission to move Montgomery's remains from Quebec to New York. In June 1818, Montgomery's remains began their journey. On July 4, they arrived in Albany and took a boat down the Hudson River to New York City. Janet stood on her porch and watched the boat. She fainted when she saw it. When his remains arrived in New York City, 5,000 people attended the procession. His remains were buried on July 8, next to his monument at St. Paul's Chapel in Manhattan. Janet was happy with the ceremony. She wrote, "What more could I wish than the high honor that has been conferred on the ashes of my poor soldier."

Years later, Andrew Jackson wrote to Edward Livingston about Janet. He said he would visit her if he was ever close by. He wanted to shake the hand of "the revered relict of the patriotic Genrl. Montgomery." Three months after this letter, Janet died on November 6, 1824.

Memorials

Montgomery's home in Rhinebeck, New York, is now the General Montgomery House. It is a historic house museum. The building is also used for meetings of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

The United States Navy has named several ships USS Montgomery over the years. This includes a frigate started in 1776. It was burned before it was finished to prevent the British from capturing it.

The Liberty cargo ship SS Richard Montgomery, built in 1943, sank in 1944 in the Thames Estuary. It is still there, with its masts showing. Its cargo of 3,173 tons of ammunition still poses a threat to the local area.

In Philadelphia, there is a statue of Montgomery in Fairmount Park, near the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Places Named After Him

Fort Montgomery, a large stone fort with 125 guns on Lake Champlain, was named for the General. Its construction began in 1844. It was designed to guard the important border between Canada and the United States. Only ruins remain today.

Many places are named after Montgomery. Counties named for him are in North Carolina, Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Georgia, Virginia, and Kentucky.

Cities and towns named for him include Montgomery, Alabama, which is that state's capital. Others are Montgomery, Minnesota and Montgomery, Vermont. There is also a township in New Jersey, a town and village in New York, and a town in Massachusetts.

Richard Montgomery High School in Rockville, Maryland, is named after him. It is located in Montgomery County, which is also named for him. Montgomery Place, a large house in Barrytown, New York, was built in 1803. It was named in his honor by his widow. General Montgomery had planned it before he left Grassmere in 1775.

Montgomery Street in Savannah, Georgia, is named for him.

Legacy

Montgomery is mentioned on a plaque at Fort Saint-Jean. The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada put it up in 1926. It says: "Constructed in 1743 by M. de Léry under orders from Governor la Galissonnière. This post was for all the military expeditions towards Lake Champlain. On August 31, 1760, Commandant de Roquemaure had it blown up in accordance with orders from the Governor de Vaudreuil in order to prevent its falling into the hands of the English. Rebuilt by Governor Carleton, in 1773. During the same year, under the command of Major Charles Preston of the 26th Regiment, it withstood a 45 day siege by the American troops commanded by General Montgomery."

|

See also

In Spanish: Richard Montgomery para niños

In Spanish: Richard Montgomery para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |