Benedict Arnold's expedition to Quebec facts for kids

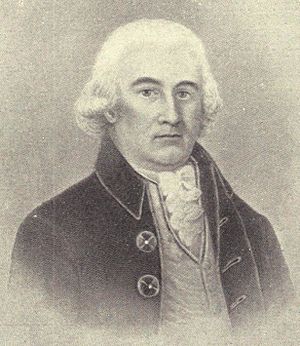

In September 1775, during the early days of the American Revolutionary War, Colonel Benedict Arnold led about 1,100 American soldiers on a difficult journey. They traveled from Cambridge to Quebec City in what is now Canada. This trip was part of a bigger plan to invade the British Province of Quebec. Another American army, led by Richard Montgomery, was invading Quebec from a different direction.

Arnold's expedition faced many problems as soon as it left the last towns in Maine. Carrying their boats and supplies around waterfalls (called portages) up the Kennebec River was very hard. Their boats often leaked, ruining gunpowder and food. More than a third of the men gave up and turned back. They had not even reached the high land between the Kennebec and Chaudière rivers. This area was full of swamps, lakes, and streams. Bad weather and maps that were not correct made the journey even tougher. Many soldiers were not good at handling boats in fast-moving water. This led to more boats and supplies being lost as they went down the fast-flowing Chaudière River toward the Saint Lawrence River.

By November, when Arnold reached the towns near the Saint Lawrence River, his group had shrunk to 600 starving men. They had traveled about 560 kilometers (350 miles) through wild lands that were poorly mapped. This was twice the distance they had expected! Arnold's troops crossed the Saint Lawrence River on November 13 and 14. Local French-speaking Canadiens helped them. They tried to attack Quebec City but failed. So, they moved back to Point-aux-Trembles to wait for Montgomery. When Montgomery arrived, they launched an unsuccessful attack on the city. Arnold was later promoted to brigadier general for his leadership.

Today, Arnold's route through northern Maine is known as the Arnold Trail to Quebec. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Some places along the route are named after people from the expedition.

Contents

Why Invade Quebec?

On May 10, 1775, soon after the American Revolutionary War began, Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen captured Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. Arnold knew that Quebec did not have many soldiers defending it. There were only about 600 regular British troops in the whole province. Arnold had also heard that the French-speaking Canadiens might support the American forces.

Arnold and Allen told the Second Continental Congress that Quebec should be taken from the British. They warned that the British could use Quebec as a base to attack American areas. At first, Congress did not want to invade Quebec. But in July, they worried that the British might use Quebec to move troops into New York. So, they changed their minds and approved an invasion of Quebec through Lake Champlain. Major General Philip Schuyler was put in charge of this task.

Planning the Secret Route

Arnold had hoped to lead the main invasion. Since he couldn't, he decided to try a different way to reach Quebec. In early August, he went to Cambridge and spoke with George Washington, the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. Arnold suggested a second invasion force from the east, heading straight for Quebec City. Washington liked the idea. He sent a message to General Schuyler to make sure both forces would work together.

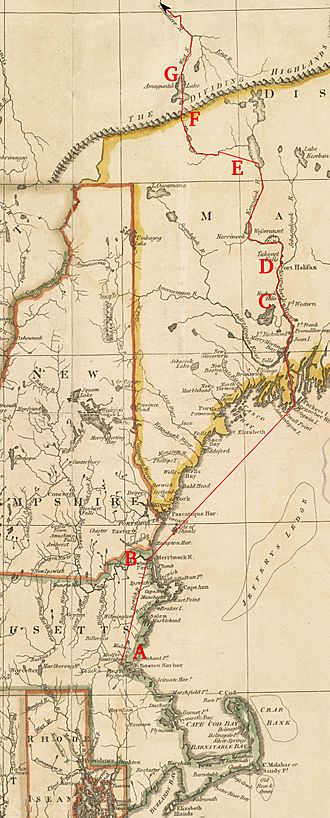

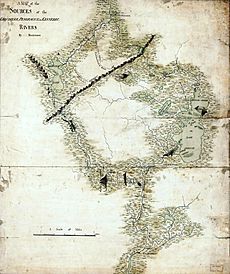

Arnold's plan was for his expedition to sail from Newburyport, Massachusetts up the Kennebec River to Fort Western (now Augusta, Maine). From there, they would use shallow boats called bateaux to go further up the Kennebec. Then, they would cross the high land to Lake Mégantic and travel down the Chaudière River to Quebec. Arnold thought the 290 kilometers (180 miles) from Fort Western to Quebec would take only 20 days. However, not much was known about this route. Arnold had a map and journal from a British engineer named John Montresor. But Montresor's descriptions were not very detailed, and the map had some errors or hidden information.

Washington introduced Arnold to Reuben Colburn, a boat builder from Gardinerstown, Maine. Colburn offered to help. Arnold asked him for details about the route, British ships, and how long it would take to build the boats. Colburn went back to Maine on August 21 to get this information. He asked Samuel Goodwin, a local surveyor, to make maps for Arnold. Goodwin, who was known to support the British, provided maps that were not accurate.

On September 2, Washington received a letter from General Schuyler agreeing to the plan. Washington and Arnold immediately started gathering troops and ordering supplies.

Getting Ready for the Journey

Many soldiers around Boston were bored because there wasn't much fighting after the Battle of Bunker Hill in June. They were eager for action. Arnold chose 750 men from those who wanted to join the expedition. Most were divided into two groups, or battalions. One was led by Lieutenant Colonel Roger Enos and the other by Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Greene. The rest were in a third group under Daniel Morgan. This group included 250 expert riflemen from Virginia and Pennsylvania. These frontiersmen were better at fighting in the wilderness than in a siege. The total force was about 1,100 men. Famous people like Aaron Burr and Henry Dearborn also volunteered.

Washington and Arnold were concerned about how Native Americans and French Canadians would react. On August 30, Washington met with an Abenaki chief. The chief said, "The Indians of Canada in general, and also the French, are greatly in our favor." Four Abenaki scouts joined the expedition.

From Cambridge to Fort Western

On September 2, as soon as General Schuyler agreed, Arnold wrote to Nathaniel Tracy, a merchant in Newburyport. He asked Tracy to find enough ships to take the expedition to Maine without being noticed by British ships. Both Arnold and Washington thought the sea trip was the most dangerous part.

The expedition left Cambridge on September 11, marching to Newburyport. The first soldiers to leave were from that area, so Arnold gave them extra time to see their families. The last troops marched on September 13. Arnold rode from Cambridge to Newburyport on September 15 after buying the last supplies.

Strong winds and fog delayed their departure from Newburyport until September 19. In 12 hours, they reached the mouth of the Kennebec River. They spent the next two days sailing up the river. They arrived in Gardinerston on September 22. For the next few days, they stayed at Reuben Colburn's house. They organized supplies and got the boats ready. Arnold inspected the boats Colburn had quickly built. He found them "very badly built" and "smaller than the directions given." Colburn and his team spent three more days building additional boats.

The British noticed Arnold's movements. General Thomas Gage in Boston knew Arnold's troops "gone to Canada and by way of Newburyport." But he thought they were going to Nova Scotia, which had few defenses. Admiral Samuel Graves later learned about Arnold's real plans. On October 18, he reported that the American troops "went up the Kennebec River, and 'tis generally believed are for Quebec."

Scouting Ahead

As the troops arrived, Arnold sent some men in the ready boats up the Kennebec River to Fort Western. Others walked on a path to Fort Halifax, 72 kilometers (45 miles) up the Kennebec. While waiting for more boats, Arnold heard from scouts Colburn had sent out. They reported rumors of a large Mohawk force near the French settlements on the Chaudière River. These rumors came from Natanis, a Native American believed to be spying for Quebec's governor, General Guy Carleton. Arnold didn't believe the reports.

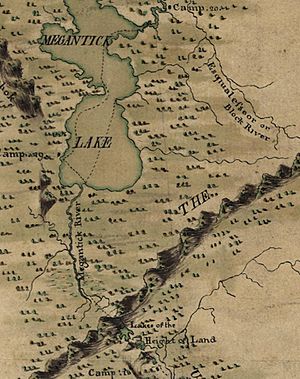

Arnold and most of his force reached Fort Western by September 23. The next day, Arnold sent two small groups up the Kennebec. One group was to scout as far as Lake Mégantic. The second group was to map the route to the Dead River. This place was known as the Great Carrying Place. Arnold wanted to know how far they could travel each day.

Early Challenges on the Trail

The full expedition left Fort Western on September 25. Morgan's riflemen went first, making trails when needed. Colburn and his boat builders followed, ready to repair boats. Morgan's group traveled light, while the last group, led by Lieutenant Colonel Enos, carried most of the supplies. The expedition reached Fort Halifax, an old fort from the French and Indian War, on the second day. There was a rough path from Fort Western, so some men and supplies went by land. Arnold traveled in a lighter canoe to move quickly among the troops.

Arnold reached Norridgewock Falls, the last settlements on the Kennebec, on October 2. Even at this early stage, problems were clear. The boats were leaking, spoiling food and needing constant repairs. The men were always wet, not just from leaks but also from pulling the heavy boats upstream. As temperatures dropped below freezing, many got colds and dysentery, making them weak.

Carrying boats around Norridgewock Falls, about 1.6 kilometers (one mile), took almost a week. Oxen from local settlers helped. Arnold didn't leave until October 9. Colburn's crew spent time fixing the boats. Most of the expedition reached the Great Carrying Place on October 11, and Arnold arrived the next day. This part of the journey was made harder by heavy rains, which made the portages very muddy.

The Great Carrying Place

The Great Carrying Place was a portage of about 19 kilometers (12 miles). It bypassed a part of the Dead River that was impossible to travel by boat. The portage included climbing about 305 meters (1,000 feet) to the highest points, with three ponds along the way. Lieutenant Church, who surveyed the route, said it was a "bad road but capable of being made good." This turned out to be too hopeful.

The first part of the main group, led by Daniel Morgan, met Lieutenant Steele's scouting party. This party had successfully scouted the route to the high land above the Dead River. But the men were almost starving. Their supplies were gone, and they were mostly eating fish, moose, and duck. Most of the men continued to hunt for food as the expedition went on.

Church had not fully described the heavy rains and swampy conditions between the first and second ponds. Rain and snow slowed the long portage. The expedition had its first death when a falling tree killed one man. Some men who drank the still water became very sick. Arnold had to order a shelter built at the second pond for the sick. He also sent some men back to Fort Halifax for supplies they had left there.

The first two groups finally reached the Dead River on October 13. Arnold arrived three days later. At this point, Arnold wrote letters to Washington and Montgomery about his progress. Several letters meant for Montgomery were captured. They were given to Quebec's Lieutenant Governor Hector Theophilus de Cramahé. This was the first time Quebec knew the expedition was coming. Arnold also sent the survey team out again to mark the trail all the way to Lake Mégantic.

Struggling Up the Dead River

Moving up the Dead River was extremely slow. Even though its name suggested slow currents, the river was flowing fast. The men had trouble rowing and pushing against the current. The leaky boats spoiled more food, forcing Arnold to cut everyone's food in half. Then, on October 19, it started pouring rain, and the river began to rise. Early on October 22, the men woke up to find the river had flooded their camp. They had to quickly move to higher ground for safety. When the sun rose, they were surrounded by water.

After spending most of that day drying out, the expedition left on October 23. They lost valuable time when some men mistakenly left the Dead River and went up a side branch, fooled by the high water. Soon after, seven boats overturned, ruining the rest of their food. This accident made Arnold think about turning back. He called his officers for a meeting. Arnold explained that the situation was bad, but he thought they should continue. The officers agreed. They decided to send an advance party ahead as fast as possible to the French settlements on the Chaudière River to get supplies. The sick and weak were to return to American settlements in Maine.

Further back, Lieutenant Colonel Greene and his men were starving. They had little flour and were eating candle tallow and shoe leather to survive. On October 24, Greene tried to catch up with Arnold but couldn't. When he returned to camp, Lieutenant Colonel Enos had arrived. They held their own meeting. Enos's captains all wanted to turn back, even though Arnold had ordered them to keep going. In the meeting, Enos voted to continue, which broke a tie. But after the meeting, he told his captains that because they insisted on returning, he would agree. After giving Greene's men some of his supplies, Enos and 450 men turned back.

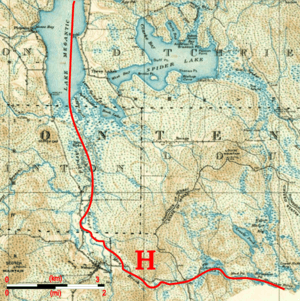

This 1924 map shows the same area with Arnold's route (H). Notice Spider Lake and swamps east of Lake Mégantic; some of the expedition got lost here for days.

|

Reaching Lake Mégantic

The inaccurate maps caused problems when the expedition reached the high land. Parts of the advance party got lost in swampy areas (like Spider Lake on the map above) that were not on their maps. This delayed them from reaching Lake Mégantic. Although this group crossed the high land on October 25, they didn't reach the lake until two days later. On October 28, the advance party went down the upper Chaudière River. They lost three boats when they overturned and crashed into rocks above some waterfalls. The next day, they met some Penobscot Native Americans. These people confirmed they were close to Sartigan, the southernmost French settlement on the Chaudière.

When Arnold reached Lake Mégantic, he sent a man back to the two remaining groups. He gave them instructions on how to get through the swampy lands above the lake. However, Arnold's description included information from the incorrect maps that he hadn't seen on his route. Because of this, some parts of the expedition spent two days lost in swamps. Most of the group finally reached the waterfalls on the upper Chaudière on October 31. Along the way, Captain Henry Dearborn's dog was eaten. He wrote in his diary: "[They ate] every part of him, not excepting his entrails; and after finishing their meal, they collected the bones and carried them to be pounded up, and to make broth for another meal."

Arriving at Quebec

Arnold first met local people on October 30. They felt sorry for his group and gave them food and cared for the sick. Some were paid well, while others refused money. Arnold handed out copies of a letter from Washington asking the locals to help. Arnold also promised to respect their people, property, and religion. Jacques Parent, a Canadien from Pointe-Levi, told Arnold that Lieutenant Governor Cramahé had ordered all boats on the south side of the Saint Lawrence to be destroyed. This was after Cramahé received Arnold's intercepted letters.

On November 9, the expedition finally reached the Saint Lawrence River at Pointe-Levi, across from Quebec. Arnold had about 600 of his original 1,100 men. The journey had been 560 kilometers (350 miles), not the 290 miles Arnold and Washington had expected. From John Halstead, a businessman, Arnold learned that his messenger had been arrested and some of his letters captured. Halstead's mill became the meeting point for crossing the Saint Lawrence. Some of Arnold's men bought canoes from the locals and Native Americans. They then carried them from the Chaudière to the mill. The forces crossed the Saint Lawrence on the night of November 13–14 after three days of bad weather. They likely crossed the 1.6-kilometer (mile-wide) river between two British warships, HMS Hunter and HMS Lizard.

Quebec City was defended by about 150 soldiers, 500 local fighters, and 400 marines from the warships. When Arnold and his troops reached the Plains of Abraham on November 14, Arnold sent a messenger to demand the city's surrender. But it didn't work. The Americans had no cannons and were barely fit to fight. They faced a strong, fortified city. After hearing rumors of an attack from the city, Arnold decided on November 19 to move back to Pointe-aux-Trembles. He waited there for Montgomery, who had recently captured Montreal.

What Happened Next

When Montgomery arrived at Pointe-aux-Trembles on December 3, the combined forces returned to Quebec City. They began a siege and finally attacked it on December 31. The battle was a terrible loss for the Americans. Montgomery was killed, Arnold was wounded, and Daniel Morgan was captured along with over 350 men. Arnold learned after the battle that he had been promoted to brigadier general for leading the expedition.

The invasion ended with a retreat back to Fort Ticonderoga in the spring and summer of 1776. Arnold, who led the army's rear guard during the retreat, managed to slow down the British. This stopped them from trying to reach the Hudson River in 1776.

Enos and his group arrived back in Cambridge in late November. Enos was put on trial, charged with "quitting his commanding officer without leave." He was found not guilty and returned to service.

Reuben Colburn was never paid for his work, even though Arnold and Washington had promised. The expedition caused him financial ruin.

Henry Dearborn settled on the Kennebec River after the war. He later became Secretary of War in 1801. Private Simon Fobes, who wrote a journal about the expedition, was captured at Quebec. He and two others escaped in August 1776. They traveled back the same route in reverse, again with few supplies. They had better weather and used equipment the expedition had left behind. Fobes reached his home in Massachusetts in September and rejoined the army.

Lasting Impact

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Arnold Trail to Quebec

|

|

A marker in Eustis, Maine that remembers the expedition.

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Built | 1775 |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 69000018 |

| Added to NRHP | October 1, 1969 |

Many places along the expedition's route are named after it. East Carry Pond, Middle Carry Pond, and West Carry Pond are all on the portage route at the Great Carrying Place. Arnold Pond is the last pond on the Dead River before crossing the high land. Mount Bigelow in Maine was named after Major Timothy Bigelow, one of Arnold's officers.

The wild part of the route through Maine, from Augusta to the Quebec border, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1969. The Major Reuben Colburn House, where Arnold stayed, is now a historic site. Both Fort Western and Fort Halifax are also important historic landmarks.

There are historical markers in places like Danvers, Massachusetts, Moscow, Maine, and Skowhegan, Maine that remember Arnold's expedition. In Eustis, Maine, near Flagstaff Lake, there is another marker. The lake was created in the 20th century by damming the Dead River, which flooded part of the expedition's route.

In the fall of 1975, people reenacted this expedition as part of the United States Bicentennial celebrations.

|

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |