Ethan Allen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ethan Allen

|

|

|---|---|

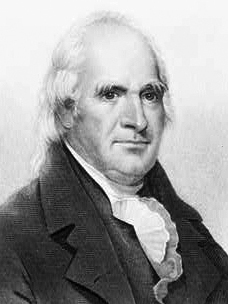

An engraving showing Ethan Allen demanding the surrender of Fort Ticonderoga.

|

|

| Born | January 21, 1738 Litchfield, Connecticut Colony, British America |

| Died | February 12, 1789 (aged 51) Burlington, Vermont Republic |

| Buried |

Greenmount Cemetery, Burlington

|

| Allegiance | Connecticut Colony (1757) United Colonies (1775–1776) United States (1778–1781) Vermont Republic (1779–1780) |

| Service/ |

Connecticut Militia Continental Army Vermont Militia |

| Rank | Major general (Vermont Republic) Colonel (Continental Army) |

| Commands held | Green Mountain Boys Fort Ticonderoga |

| Battles/wars | |

| Children | Fanny Allen |

| Relations | Ira Allen (brother) |

| Other work | Farmer, politician, land speculator, philosopher |

Ethan Allen (January 21, 1738 – February 12, 1789) was a farmer, soldier, and politician who played a key role in the founding of Vermont. He is most famous for leading a group called the Green Mountain Boys and for their daring capture of Fort Ticonderoga during the American Revolutionary War.

Born in rural Connecticut, Allen grew up on the frontier. He became involved in a land dispute in the 1760s in an area called the New Hampshire Grants, which would later become Vermont. To protect the land of settlers from New York authorities, he formed the Green Mountain Boys. This group used threats and force to drive away New York officials.

When the Revolutionary War began, Allen and his Green Mountain Boys captured the important British base, Fort Ticonderoga, in May 1775. Later that year, he was captured by the British during a failed attack on Montreal. He was held as a prisoner of war until being released in 1778.

After his release, Allen returned to Vermont, which had declared itself an independent republic. He worked to get the Continental Congress to recognize Vermont as the 14th state. He also wrote books about his adventures and his philosophical ideas.

Contents

Early Life

Ethan Allen was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, the first of eight children. His family moved to the town of Cornwall soon after he was born. As a boy, Allen was known for being smart and enjoying debates about the meaning of Bible passages. His brothers, Ira and Heman, also became important figures in Vermont's history.

Cornwall was a frontier town when Allen was young. His father, Joseph Allen, was a successful farmer. He wanted Ethan to go to Yale College, so Ethan began studying with a local minister.

However, Allen's father died in 1755, and he had to end his studies to take care of the family farm. In 1762, he married Mary Brownson, and they had five children. During this time, Allen also became part owner of an iron furnace.

Allen was very interested in philosophy and big ideas. He became friends with a doctor named Thomas Young, who taught him about political theory. They even started writing a book together to challenge organized religion, as Allen had become a Deist, believing in God but not in the rules of a specific church.

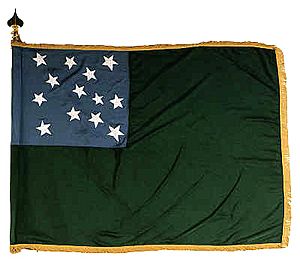

The Green Mountain Boys

In the mid-1700s, the governor of New Hampshire, Benning Wentworth, sold land grants in the area that is now Vermont. Many people bought this land and started farms. However, in 1764, the King of Great Britain decided the land actually belonged to New York.

New York officials then told the settlers they had to pay large fees to keep the land they had already bought. The settlers, who were mostly farmers, did not have the money and felt this was unfair.

Leading the Resistance

In 1770, the settlers asked Ethan Allen to help them fight New York's claim in court. When the court sided with New York, Allen and the settlers refused to give up. They met at the Catamount Tavern and formed a militia to protect their land. They called themselves the Green Mountain Boys.

Allen was chosen as their leader, or "Colonel Commandant." For several years, the Green Mountain Boys rode through the territory, scaring off New York surveyors and settlers. They sometimes destroyed property but tried to avoid bloodshed. New York's governor, William Tryon, offered a reward for Allen's capture, but no one could catch him.

During this time, Allen and his brothers also started the Onion River Company. They bought large areas of land in the territory, which later became the city of Burlington, Vermont.

The American Revolutionary War

When the American Revolutionary War began in April 1775, the fighting gave Allen and the Green Mountain Boys a new purpose. They decided to fight for the Patriot cause against the British.

Capturing Fort Ticonderoga

In May 1775, Allen was asked to help capture Fort Ticonderoga, a key British fort on Lake Champlain. He gathered about 130 of his Green Mountain Boys, who were joined by other militiamen from Massachusetts and Connecticut.

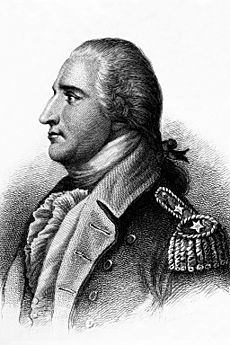

Just before the attack, Benedict Arnold, a colonel from Massachusetts, arrived with orders to lead the mission. The Green Mountain Boys refused to follow anyone but Allen. To avoid a fight, Allen and Arnold agreed to lead the attack together.

In the early morning of May 10, they crossed the lake with only 83 men and snuck into the fort. They surprised the sleeping British soldiers. Allen went straight to the commander's room and demanded he surrender. When the British officer asked by what authority, Allen famously shouted, "In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!"

The fort was captured without a single shot being fired. The cannons and supplies taken from Ticonderoga were later used by the Continental Army to drive the British out of Boston.

Attempt to Invade Canada

After the victory at Ticonderoga, Allen wanted to continue the fight. He joined the American invasion of Quebec, hoping to convince French-Canadians to join the revolution.

In September 1775, Allen and a small force of men tried to capture the city of Montreal. He planned a two-sided attack with another officer, Major John Brown. However, Brown's forces never arrived. British General Guy Carleton learned of Allen's plan and surrounded him. In the Battle of Longue-Pointe, Allen was captured along with about 30 of his men.

A Prisoner of War

Allen spent the next two and a half years as a prisoner of the British. At first, he was kept in chains on a ship in Montreal. He was then sent to England and held in Pendennis Castle.

His conditions improved after he wrote a letter describing his harsh treatment. The British government, not wanting to be seen as cruel, sent him back to America to be treated as a prisoner of war. He was held on prison ships off the coast and later paroled in New York City.

Finally, on May 3, 1778, he was released in a prisoner exchange. He reported to General George Washington at Valley Forge, who gave him the rank of Colonel in the Continental Army as a reward for his bravery.

A Leader in Vermont

When Allen returned home, he was greeted as a hero. He learned that while he was a prisoner, Vermont had declared itself an independent nation in 1777, called the Vermont Republic.

Political Activities

Allen quickly became involved in Vermont's politics. He worked to get the Continental Congress to recognize Vermont as a state, but states like New York blocked this because they still claimed the land.

To protect Vermont, Allen and other leaders, including his brother Ira, took a controversial step. Between 1780 and 1783, they held secret talks with the British governor of Quebec. They discussed the possibility of making Vermont a British province in exchange for protection. These talks, known as the Haldimand Affair, were seen by some as treasonous, but they showed how far Vermont's leaders would go to remain independent.

In 1779, Allen published a book about his time as a prisoner, called A Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen's Captivity. It became a bestseller and made him even more famous.

Later Life and Legacy

After the Revolutionary War ended in 1783, Allen's role in politics became less important. Vermont's population was growing, and its government was no longer run by just a few families.

In 1784, Allen married his second wife, a widow named Frances "Fanny" Montresor Brush Buchanan. They had three children and a happy marriage. The family moved to Burlington in 1787, which was then a small but growing town.

In his final years, Allen wrote another book called Reason: the Only Oracle of Man. In it, he shared his philosophical ideas and challenged the religious beliefs of his time. The book was not popular and did not sell well.

Death

On February 11, 1789, Allen traveled across the frozen Lake Champlain to visit a cousin. On the journey home the next day, he fell ill and lost consciousness. He died at home a few hours later on February 12, 1789. He was 51 years old.

Allen was buried in Burlington, and his funeral was attended by many people who saw him as their champion.

Memorials

Although we do not have any portraits of Ethan Allen made during his lifetime, he is remembered as a tall, strong, and commanding figure.

Today, Ethan Allen is honored in many ways:

- A statue of him represents Vermont in the National Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol.

- The Ethan Allen Homestead and Museum is located at his former home in Burlington.

- Two U.S. Navy ships and several military forts have been named after him.

- The Ethan Allen Express is an Amtrak train that runs from New York City to Burlington.

Family

Allen's daughter, Fanny Allen, became well-known when she converted to Catholicism and became a nun. His grandson, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, served as a general for the Union Army during the American Civil War.

See Also

In Spanish: Ethan Allen para niños

In Spanish: Ethan Allen para niños