Saratoga campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Saratoga campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

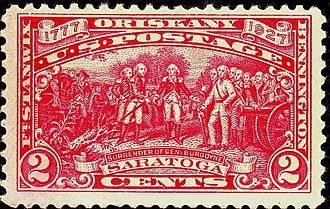

Surrender of General Burgoyne by John Trumbull |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Oneida |

Iroquois (minus Oneida) |

||||||

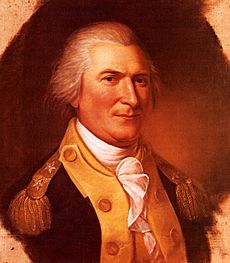

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Charles de Langlade |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000 | 8,500 (Burgoyne) 1,600 (St. Leger) 3,000 (Clinton) |

||||||

| A Campaign streamer embroidered "Saratoga 2 July–17 October 1787" is awarded to American military units that participated in this campaign. | |||||||

The Saratoga campaign in 1777 was a major event in the American Revolutionary War. The British wanted to control the important Hudson River valley. This would cut off New England from the other American colonies.

The main British army was led by General John Burgoyne. He started with about 8,000 soldiers. They moved south from Quebec in June. They traveled by boat on Lake Champlain and Lake George. Then they marched down the Hudson Valley to Saratoga.

The campaign's turning point happened in August at the Battle of Bennington. American militia from Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts defeated about 1,000 German soldiers from Burgoyne's army. After more losses in the Battles of Saratoga in September and October, Burgoyne's army was surrounded. He had to surrender to American General Horatio Gates on October 17.

This British loss was very important. It convinced France to join the war as an ally of the United States. France then provided money, soldiers, and supplies. This help was key to the American victory in the war.

Contents

- British War Strategy

- American War Strategy

- International Interest in the War

- Campaign Begins

- Ticonderoga Falls to the British

- Reactions and Delays

- St. Leger's Expedition

- Growing Difficulties for the British

- American Fortunes Change

- Saratoga Battles

- British Surrender

- Aftermath of the Campaign

- Consequences of the Victory

- Remembering the Campaign

- See also

British War Strategy

By late 1776, British leaders in London realized it was hard to control New England. Many Patriots lived there. So, they decided to focus on the middle and southern colonies. They hoped to find more Loyalists there.

In December 1776, General John Burgoyne met with Lord Germain. Germain was the British official in charge of the war. They planned the strategy for 1777. Britain had two main armies in North America. One was General Guy Carleton's army in Quebec. The other was General William Howe's army, which had taken New York City.

Howe's Plan to Attack Philadelphia

On November 30, 1776, General Howe wrote to Lord Germain. Howe was the British commander in North America. He suggested a big plan for 1777. If he got more soldiers, he could send 10,000 men up the Hudson River to take Albany, New York. Then, he could capture Philadelphia, the American capital.

But Howe soon changed his mind. He thought the extra soldiers might not arrive. Also, the American army had retreated, making Philadelphia an easier target. So, Howe decided to make capturing Philadelphia his main goal for 1777. He sent this new plan to Germain, who received it in February 1777.

Burgoyne's Plan to Capture Albany

Burgoyne wanted to lead a large army. He suggested invading New York from Quebec to cut off New England. General Carleton had tried this in 1776 but stopped because it was too late in the year. Carleton was criticized for this.

Burgoyne presented his plan to Lord Germain on February 28, 1777. Germain approved it and gave Burgoyne command of the main attack.

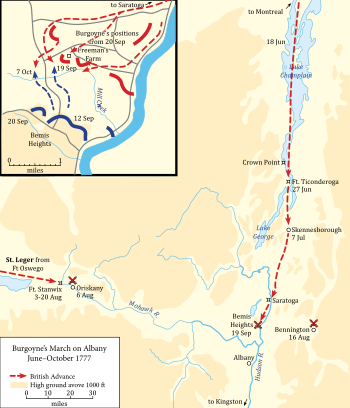

Burgoyne's plan had two parts. He would lead about 8,000 men south from Montreal. They would follow Lake Champlain and the Hudson River Valley. A second group of about 2,000 men, led by Barry St. Leger, would move east from Lake Ontario. They would go down the Mohawk River valley. Both groups would meet in Albany. There, they would join with Howe's army coming up the Hudson. This would cut off New England from the other colonies.

The last part of Burgoyne's plan, Howe's advance from New York City, caused problems. Germain approved Burgoyne's plan after seeing Howe's plan for Philadelphia. It's unclear if Germain told Burgoyne about Howe's changed plans. Some say he did, others say Burgoyne found out later.

Historians debate if Germain, Howe, and Burgoyne understood each other. Germain approved Howe's Philadelphia trip. He did not order Howe to go to Albany. But Germain also sent Howe a copy of his orders to Carleton. These orders said the northern army should meet Howe's army in Albany.

A letter from Germain to Howe on May 18, 1777, said the Philadelphia trip should be done in time to help Burgoyne. But Howe did not get this letter until after he left New York. Howe chose a long sea route to Philadelphia. This made it impossible for him to help Burgoyne.

Burgoyne returned to Quebec on May 6, 1777. He had a letter from Lord Germain with the plan. This caused problems between Burgoyne and General Carleton. Burgoyne outranked Carleton, but Carleton was still governor of Quebec. Germain's orders limited Carleton's role. This upset Carleton. He later resigned and refused to send Quebec troops to guard captured forts.

American War Strategy

George Washington and other American generals did not know the British plans for 1777. Washington and Generals Horatio Gates and Philip Schuyler were in charge of defending the Hudson River. They wondered what Howe's army in New York would do. They knew little about the British forces in Quebec.

Because of this uncertainty, the American forts in the Mohawk and Hudson valleys were not greatly strengthened. Schuyler did send a large regiment to fix up Fort Stanwix in the Mohawk valley in April 1777. Washington also kept four regiments ready at Peekskill, New York. They could be sent north or south as needed.

By June 1777, American troops were spread across New York. About 1,500 soldiers were along the Mohawk River. About 3,000 were in the Hudson River highlands under General Israel Putnam. Schuyler commanded about 4,000 troops, including local militia and soldiers at Ticonderoga.

International Interest in the War

Since the Seven Years' War, French foreign ministers believed that American independence would help France and hurt Britain. They also thought trying to get back parts of New France would not help. When the war started in 1775, the Comte de Vergennes, the French Foreign Minister, suggested secret French and Spanish support for the Americans.

Vergennes watched news from North America closely. He wanted to remove anything that stopped Spain from joining the war. Vergennes even suggested war to King Louis XVI in August 1776. But news of Howe capturing New York City stopped that plan.

Campaign Begins

Most of Burgoyne's army arrived in Quebec in spring 1776. They helped drive American troops out of the province. Besides British soldiers, there were German troops from Hesse-Cassel, Hesse-Hanau (called Hessians), and Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. These Germans were led by Baron Friedrich Adolph Riedesel.

About 200 British and 300-400 Germans were sent with St. Leger's Mohawk valley group. About 3,500 men stayed in Quebec to protect the province. The rest joined Burgoyne for the Albany campaign. Burgoyne expected about 2,000 Quebec militia to join, but Carleton only raised three small companies. Burgoyne also hoped for 1,000 Native American allies. About 500 joined him between Montreal and Crown Point.

Burgoyne's army had trouble with transportation before leaving Quebec. They expected to travel mostly by water. So, they had few wagons, horses, or other animals to move supplies on land. Carleton only ordered carts in early June. These carts were poorly made, and the civilian drivers often left.

On June 13, 1777, Burgoyne and Carleton reviewed the troops at St. John's. This was just north of Lake Champlain. Burgoyne was officially given command. Six sailing ships and many transport boats moved the army south on the lake.

The army Burgoyne launched the next day had about 7,000 regular soldiers and over 130 cannons. His soldiers were in good shape. But some, like the German dragoons, were not ready for fighting in the wilderness.

Colonel St. Leger's group was also ready by mid-June. His force had British soldiers, Loyalists, Hessians, and rangers. About 750 men left Lachine, near Montreal, on June 23.

Ticonderoga Falls to the British

Burgoyne's army moved up Lake Champlain. They took over the undefended Fort Crown Point by June 30. Burgoyne's Native American allies were good at hiding his movements. General Arthur St. Clair commanded Fort Ticonderoga with about 3,000 soldiers. He did not know how strong Burgoyne's army was on July 1.

Small fights began around Ticonderoga on July 2. By July 4, most American soldiers were at Fort Ticonderoga or Mount Independence. The Americans did not know that the British could place cannons on a nearby hill called Sugar Loaf (now Mount Defiance). This hill overlooked the fort.

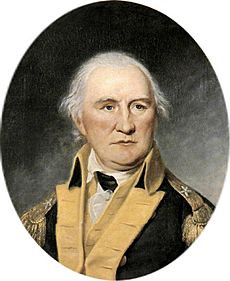

St. Clair saw British cannons on Sugar Loaf on July 5. He decided to retreat that night. Burgoyne's men took over the fort and Mount Independence on July 6. The easy surrender of the fort shocked everyone. Schuyler and St. Clair were later cleared of wrongdoing. But the Continental Congress replaced Schuyler with General Horatio Gates in August.

Burgoyne sent soldiers to chase the retreating Americans. General Fraser and some of Riedesel's troops fought hard at the Battle of Hubbardton on July 7. That same day, the main British army fought Pierse Long's men at Skenesboro. Another fight happened at the Battle of Fort Anne on July 8. These battles cost the Americans more soldiers than the British. But they showed the British that Americans would fight hard.

Burgoyne's army lost about 1,500 men from the Ticonderoga actions. He left 400 men at Crown Point and 900 at Ticonderoga. The battles that followed caused about 200 British casualties.

Most of St. Clair's army retreated through New Hampshire Grants (now Vermont). St. Clair asked the states for militia help. He also arranged to send livestock and supplies to Fort Edward on the Hudson River. St. Clair reached Fort Edward on July 12 after five hard days of marching.

Reactions and Delays

Burgoyne stayed at the house of Philip Skene in Skenesboro. He wrote letters about the British victory. When this news reached Europe, King George was happy. But the Comte de Vergennes was not, as it stopped an early plan for France to join the war. British diplomats pressured France and Spain to close their ports to American ships. This increased tensions.

On July 10, Burgoyne gave orders for the next moves. Most of the army would take the rough road from Skenesboro to Fort Edward. Heavy cannons would go down Lake George, then overland to Fort Edward. Riedesel's troops were sent toward Castleton to trick the Americans. Burgoyne chose the overland route, even though he knew it could be easily blocked. He seemed to want to avoid looking like he was retreating. Also, Philip Skene's property would benefit from the improved road.

General Schuyler, in Albany, heard about Ticonderoga's fall. He rode to Fort Edward, where he had about 700 regular soldiers and 1,400 militia. He decided to make Burgoyne's journey as hard as possible. He had trees cut down to block the roads. This slowed Burgoyne's advance, tired his troops, and used up supplies. On July 11, Burgoyne complained to Lord Germain that Americans were cutting trees and destroying bridges. Schuyler also used scorched earth tactics. This meant destroying food and supplies so the British could not use them.

Schuyler's tactics forced Burgoyne to build a road through the wilderness. This took about two weeks. They left Skenesboro on July 24 and reached Fort Edward on July 29. Schuyler had already left, retreating to Stillwater, New York. Before leaving Skenesboro, Burgoyne was joined by about 500 Native Americans. These included Ottawas, Fox, Mississaugas, Chippewas, and Iroquois. They were led by St. Luc de la Corne and Charles Michel de Langlade.

St. Leger's Expedition

Lieutenant Colonel St. Leger sailed up the St. Lawrence River and across Lake Ontario without problems. He had about 300 regular soldiers, plus 650 Canadian and Loyalist militia. They were joined by 1,000 Native Americans led by John Butler and Iroquois war chiefs Joseph Brant, Sayenqueraghta and Cornplanter.

Leaving Oswego on July 25, they marched to Fort Stanwix on the Mohawk River. They began attacking it on August 2. About 800 Tryon County militia and their Native American allies marched to help the fort. But some of St. Leger's British and Native American forces ambushed them on August 6. This was the bloody Battle of Oriskany. The Americans held the battlefield but retreated due to heavy losses. Their leader, General Nicholas Herkimer, was badly wounded. Iroquois warriors fought on both sides, starting a civil war among the Six Nations. During the Oriskany battle, the Americans from Fort Stanwix attacked the nearly empty Native American camp. This, and the many Native American losses at Oriskany, hurt their morale.

On August 10, Benedict Arnold left Stillwater, New York for Fort Stanwix. He had 800 men from Schuyler's army. He hoped to get more militia at Fort Dayton on August 21. But Arnold only found about 100 militia. So, he used a trick. He arranged for a Loyalist prisoner to escape. This prisoner convinced St. Leger that Arnold was coming with a much larger army.

Because of this news, Joseph Brant and St. Leger's other Native American allies left. They took most of his supplies. St. Leger had to stop the attack and go back to Quebec. Arnold sent a small group after them. He then turned his main force east to rejoin the Americans at Saratoga. St. Leger's remaining men reached Fort Ticonderoga on September 27. They arrived too late to help Burgoyne, who was already surrounded.

Growing Difficulties for the British

The advance of Burgoyne's army to Fort Edward was like the approach to Ticonderoga. A wave of Native Americans went ahead, chasing away the small American troops there. These allies became impatient. They began attacking frontier families and settlements. This made more local people support the American rebels.

A young Loyalist settler named Jane McCrea was killed by Native Americans. This story was widely shared. Burgoyne did not punish those responsible. This made people see him as unable to control his allies. Her death became a rallying cry for the rebels.

Even though most of his army reached Fort Edward quickly, they were delayed again. The supply wagons had trouble on the rough wilderness roads. They lacked enough draft animals.

On August 3, messengers from General Howe finally reached Burgoyne's camp at Fort Edward. (Many British attempts to send messages failed because Americans captured and hanged the messengers.) The news was not good. Howe wrote on July 17 that he was sailing to capture Philadelphia. He said General Clinton, defending New York City, would "act as occurrences may direct." Burgoyne did not tell his officers what the message said.

Burgoyne realized he had a serious supply problem. He decided to follow a suggestion from Baron Riedesel. Riedesel had noticed that the area had many draft animals and horses. These could be taken for the army. On August 9, Burgoyne sent Colonel Friedrich Baum's regiment to get supplies from Bennington, Vermont. They also took some German dragoons.

Most of Baum's group never returned from the Battle of Bennington on August 16. The reinforcements Burgoyne sent were also badly beaten. This battle cost Burgoyne nearly 1,000 men and much-needed supplies. Burgoyne did not know that General John Stark had gathered 2,000 militia at Bennington. Stark's force surrounded Baum's men, killing Baum and capturing many of his soldiers.

The death of Jane McCrea and the Battle of Bennington helped the Americans. Burgoyne blamed his Native American and Canadian allies for McCrea's death. Even after the Native Americans lost 80 men at Bennington, Burgoyne showed them no thanks. As a result, Langlade, La Corne, and most of the Native Americans left the British camp. Burgoyne was left with fewer than 100 Native American scouts. He had no protection in the woods against American rangers.

American Fortunes Change

While delaying tactics worked on the battlefield, they caused problems in the Continental Congress. General Horatio Gates was in Philadelphia when Congress discussed the fall of Ticonderoga. Gates was eager to blame other generals. Some in Congress were already impatient with General George Washington. They wanted a big battle to end the British occupation.

John Adams, head of the War Committee, praised Gates. He said, "we shall never hold a post until we shoot a general." Despite objections from New York, Congress sent Gates to command the Northern Department on August 10. They also ordered states from Pennsylvania to Massachusetts to call out their militias. On August 19, Gates arrived in Albany to take charge. He was cold and arrogant. He purposely left Schuyler out of his first war meeting. Schuyler soon left for Philadelphia.

Throughout August and into September, militia companies arrived at the American camps on the Hudson. Troops Washington sent north from the Hudson Highlands also joined. These included Daniel Morgan's skilled riflemen. News of American victories at Bennington and Fort Stanwix, plus anger over Jane McCrea's death, boosted support. Gates' army grew to over 6,000 soldiers. This number did not include Stark's smaller army at Bennington.

Saratoga Battles

The "Battle of Saratoga" was actually a series of movements and two main battles over a month. In early September 1777, Burgoyne's army had just over 7,000 men. They were on the east bank of the Hudson. He knew St. Leger had failed at Stanwix. He also knew Howe would not send much help from New York City.

Burgoyne needed to find safe winter quarters. He could retreat to Ticonderoga or advance to Albany. He chose to advance. He then made two important decisions. He cut off communications to the north. This meant he did not need to keep many forts between his position and Ticonderoga. He also decided to cross the Hudson River while his army was still strong. So, he ordered Riedesel's forces to abandon outposts south of Skenesboro. The army crossed the river north of Saratoga (now Schuylerville) between September 13 and 15.

Burgoyne moved carefully. Losing his Native American scouts meant he had poor information. On September 18, his army's front reached a spot north of Saratoga. This was about 4 miles (6.4 km) from the American defense line. Small fights broke out between the armies.

When Gates took over Schuyler's army, much of it was near the Mohawk River. On September 8, he ordered the army, then about 10,000 men, to Stillwater. He planned to set up defenses there. The Polish engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko found the area not good for defenses. So, a new spot was chosen about 3 miles (4.8 km) north. This was about 10 miles (16 km) south of Saratoga. Here, Kosciusko designed defense lines from the river to the bluffs called Bemis Heights.

General Lincoln was supposed to command the right side of these defenses. But he was leading troops for an attack on Ticonderoga. So, Gates took command of that part himself. Gates put General Arnold in charge of the army's left, the western defenses on Bemis Heights. Gates and Arnold had a good relationship at first. But it soured when Arnold chose Schuyler's friends for his staff. This, plus their difficult personalities, led to arguments.

Battle at Freeman's Farm

Both Generals Burgoyne and Arnold knew the American left side was important. Burgoyne saw that the American position could be attacked from the side. He split his forces, sending a large group west on September 19. Arnold also thought a British attack on the left was likely. He asked Gates for permission to move his forces to Freeman's Farm. Gates refused a full movement. He wanted to wait behind his defenses for a frontal attack. But he let Arnold send Daniel Morgan's riflemen and light infantry to scout.

These forces started the Battle of Freeman's Farm when they met Burgoyne's right side. In the battle, the British took control of Freeman's Farm. But they lost 600 soldiers, which was ten percent of their force.

After the battle, the fight between Gates and Arnold exploded. Gates did not mention Arnold in his official report to Congress. He also moved Morgan's company, which had been under Arnold, to his direct command. Arnold and Gates had a loud argument. Gates said General Lincoln would replace Arnold. Arnold then wrote a letter to Gates, listing his complaints. He asked to be transferred to Washington's command. Gates gave Arnold permission to leave.

Burgoyne thought about attacking again the next day. But he stopped when Fraser said many men were tired. So, he dug in his army. He waited for news of help from the south. A letter from General Clinton in New York on September 21 suggested a move up the Hudson. This might draw away some of Gates' army. Burgoyne knew his army was shrinking from desertions. He also knew they were running low on food. But he did not know the American army was growing daily.

Attack on Ticonderoga Fort

General Lincoln and Colonel John Brown attacked the British at Fort Ticonderoga. Neither side at Saratoga knew this until after their battle. Lincoln had gathered 2,000 men at Bennington by early September. They heard that the guard at Ticonderoga might be surprised. Lincoln sent three groups of 500 men to "annoy, divide, and distract the enemy." One group went to Skenesboro, which the British had left. The second went to capture Mount Independence. The third, led by John Brown, went to Ticonderoga.

On September 18, Brown surprised the British at the south end of the trail from Lake George to Lake Champlain. His men quickly moved up the trail, surprising British defenders and capturing cannons. They reached the high ground near Ticonderoga. There, they took over the "old French lines." On the way, he freed 100 American prisoners and captured nearly 300 British. His demand for the fort's surrender was refused. For the next four days, Brown's men and the fort exchanged cannon fire with little effect. Brown did not have enough men to attack the fort. He then went back to Lake George.

General Gates wrote to Lincoln on the day of Freeman's Farm. He ordered Lincoln's force back to Saratoga, saying "not one moment should be lost." Lincoln reached Bemis Heights on September 22. But his last troops did not arrive until the 29th.

Sir Henry Clinton's Diversion

General Howe had left General Sir Henry Clinton in charge of New York's defense. Clinton was told to help Burgoyne if he could. Clinton wrote to Burgoyne on September 12. He said he would "make a push at [Fort] Montgomery in about ten days" if 2,000 men could help Burgoyne. When Burgoyne got the letter, he immediately asked Clinton for advice. Should he advance or retreat, based on Clinton's chances of reaching Albany? Burgoyne said if he didn't get a reply by October 12, he would have to retreat.

On October 3, Clinton sailed up the Hudson River with 3,000 men. On October 6, he captured the highland forts Clinton and Montgomery. Burgoyne never received Clinton's messages after this victory. All three messengers were captured. Clinton then removed the chain across the Hudson. He sent a raiding force up the river. They reached Livingston Manor on October 16 before turning back. Gates only learned of Clinton's movements after the Battle of Bemis Heights.

Battle at Bemis Heights

More militia units joined the American camp. With Lincoln's 2,000 men, the American army grew to over 15,000 soldiers. Burgoyne, who had put his army on short food supplies on October 3, held a meeting the next day. They decided to send about 1,700 men to scout the American left side. Burgoyne and Fraser led this group on the afternoon of October 7.

Their movements were seen. Gates wanted to send only Daniel Morgan's men to fight them. Arnold said this was not enough. A larger force was needed. Gates, annoyed by Arnold's tone, dismissed him. He said, "You have no business here." However, Gates did listen to similar advice from Lincoln. Besides sending Morgan's company around the British right, he also sent Enoch Poor's brigade against Burgoyne's left. When Poor's men made contact, the Battle of Bemis Heights began.

The first American attack was very effective. Burgoyne tried to order a retreat, but his aide was shot before the order could be given. In fierce fighting, Burgoyne's army's sides were exposed. The German soldiers in the center held against a strong attack. General Fraser was badly wounded in this part of the battle. After Fraser fell and more American troops arrived, Burgoyne ordered his remaining force to retreat behind their defenses.

General Arnold, frustrated by the fighting he wasn't in, rode from American headquarters to join the battle. Arnold, who some said was very angry, led the attack on the British position. The right side of the British line had two dirt forts called redoubts. These were on Freeman's Farm. German soldiers under Heinrich Breymann and light infantry under Lord Balcarres defended them. Arnold first rallied troops to attack Balcarres' redoubt, but it failed.

He then bravely rode through the gap between the two redoubts. This space was guarded by a small group of Canadian irregulars. Learned's men followed. They attacked the open rear of Breymann's redoubt. Arnold's horse was shot, pinning him and breaking his leg. Breymann was killed in the fierce fight, and his position was taken. But night was falling, and the battle ended. Nearly 900 of Burgoyne's soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured. The Americans lost about 150.

British Surrender

Simon Fraser died from his wounds the next day. Burgoyne then ordered his army to retreat. Their defenses had been constantly attacked by the Americans. (General Lincoln was also wounded, and Arnold was wounded too. This meant Gates lost his top two field commanders.)

It took the army almost two days to reach Saratoga. Heavy rain and American attacks slowed them down. Burgoyne was helped by American supply problems. The American army had trouble moving forward because of delays in getting food. However, Gates sent groups to the east side of the Hudson to stop any crossing attempts. By the morning of October 13, Burgoyne's army was completely surrounded. His officers voted to start talks for surrender. Terms were agreed on October 16. Burgoyne insisted on calling it a "convention" instead of a surrender.

Baroness Riedesel, wife of the German commander, wrote about the confusion and hunger of the retreating British army. Her journal describes the suffering of officers and men, and the terrified women hiding in a cellar. This shows how desperate the surrounded army was.

On October 17, Burgoyne's army surrendered with full honours of war. Burgoyne gave his sword to Gates, who immediately returned it as a sign of respect. Burgoyne's army, about 6,000 strong, marched past to stack their weapons. American and British bands played "Yankee Doodle" and "The British Grenadiers".

Aftermath of the Campaign

British troops left Ticonderoga and Crown Point in November. Lake Champlain was free of British troops by early December. American troops still had work to do. Most of the army marched south toward Albany on October 18. Other groups went east with the "Convention Army". Burgoyne and Riedesel became guests of General Schuyler. Burgoyne was allowed to return to England in May 1778. He spent two years defending his actions. He was later exchanged for over 1,000 American prisoners.

After Burgoyne's surrender, Congress declared December 18, 1777, a national day of "Thanksgiving and praise." This was the first official Thanksgiving holiday in the nation.

The Convention Army

Under the agreement, Burgoyne's army was to march to Boston. British ships would take them back to England. They promised not to fight again until they were formally exchanged. Congress asked Burgoyne for a list of his troops. This was to make sure they followed the agreement. When he refused, Congress decided not to honor the terms. The army remained prisoners.

The army was kept in simple camps across New England. Some officers were exchanged. But much of the "Convention Army" was marched south to Virginia. They remained prisoners for several years. Many men (over 1,300 in the first year) escaped and left the army. They settled in the United States.

Consequences of the Victory

JOHN WATTS de PEYSTER

Brev: Maj: Gen: S.N.Y.

2nd V. Pres't Saratoga Mon't Ass't'n:

In memory of

the most brilliant soldier of the

Continental Army

who was desperately wounded

on this spot the sally port of

BORGOYNES GREAT WESTERN REDOUBT

7th October, 1777

winning for his countrymen

the decisive battle of the

American Revolution

and for himself the rank of

On December 4, 1777, Benjamin Franklin at Versailles learned that Philadelphia had fallen and Burgoyne had surrendered. Two days later, King Louis XVI agreed to talks for an alliance. The treaty was signed on February 6, 1778. France declared war on Britain a month later. Fighting began with naval battles in June. Spain joined the war in 1779 as an ally of France.

The British government of Lord North faced strong criticism when news of Burgoyne's surrender reached London. People said Lord Germain was "incapable of conducting a war." Lord North offered peace terms to Parliament that did not include independence. When these were delivered to Congress, they were rejected.

Remembering the Campaign

Most of the battlefields from the campaign have been preserved. They are usually state or national parks, or historic sites. Some monuments are listed as National Historic Landmarks. Many battles are re-enacted regularly. The Battle of Bennington is celebrated in Vermont on Bennington Battle Day.

Benedict Arnold's contributions to the American success are especially remembered. The obelisk at Saratoga National Historical Park has statues of three generals: Gates, Schuyler, and Morgan. The fourth spot, for Arnold, is empty. The park also has the Boot Monument. It honors Arnold's contribution in the second Saratoga battle without naming him.

The World War II aircraft carriers USS Saratoga (CV-3) and USS Bennington (CV-20) were named after battles of the Saratoga campaign.

|

See also

In Spanish: Campaña de Saratoga para niños

In Spanish: Campaña de Saratoga para niños