Invasion of Minorca (1781) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Conquest of Menorca andSiege of Fort St. Philip (1781) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

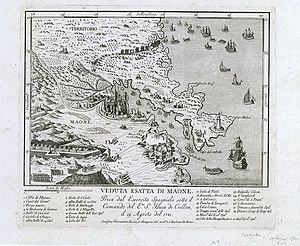

Print of the siege from 1781 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 14,000 | 3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

564 184 killed 380 wounded |

2,540 59 killed (excluding disease) 149 wounded 2,481 captured |

||||||

The Franco-Spanish forces took back Menorca (also called "Minorca") from the British in February 1782. This happened after a long siege of Fort St. Philip that lasted over five months. This victory was a key part of Spain's goals in its team-up with France against Britain during the American Revolutionary War. In the end, Menorca was given back to Spain in the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Contents

Why Menorca Was Important

Menorca is an island in the Mediterranean Sea. It has a great port called Mahón. This port was very useful for navies that didn't have their own coast in the Mediterranean. Because of this, Britain controlled Menorca for most of the 1700s.

Fort St. Philip's Castle

The entrance to Mahón's port was protected by a fort called St. Philip's Castle. After a battle in 1756, this fort was made much stronger. In that battle, a British admiral named John Byng chose to protect his ships instead of the fort. He was later punished for this. Even though France won that battle, they lost the Seven Years' War in 1763. So, Menorca went back to Britain, not to Spain, even though Spain had historical ties to the island.

Spain's Goals in the War

Spain joined France against Britain in 1779 with the Treaty of Aranjuez. One of their main goals was to get Menorca back. Taking Menorca was important because it was a base for British privateers. These were private ships allowed by the British Governor, Lieutenant-General James Murray, to capture enemy merchant ships.

Planning the Invasion

Spain had been trying to take back Gibraltar since 1779. By late 1780, Spanish leaders decided they needed to start other projects too. So, they planned to invade Menorca in early 1781. The plan was mostly made by Don Luis Berton de los Blats, also known as Duc de Crillon. He was a French general working with Spain.

The Invasion Fleet Sets Sail

On June 25, 1781, a French fleet of about 20 warships left Brest. They were secretly going to help the Spanish invasion. To trick the British, they didn't join the Spanish ships right away.

The Spanish invasion fleet left Cadiz on July 23, 1781. It had 51 ships for troops, 18 for supplies, and many others. They first sailed west to make it look like they were going to America. But at night, they turned around and passed Gibraltar on July 25. Bad winds made the convoy break up, and they had to stop near Cartagena. A few days later, the French warships quietly joined them. The combined fleet left on August 5 and saw Alicante on August 14. On August 18, they passed Cabrera island and were joined by 4 more warships. The next morning, Menorca was in sight.

How They Planned to Invade

The main plan was to land a large force at Mesquida Bay, north of Port Mahón. A smaller force would land at Alcaufar Bay, south of the port. The other two main harbors, Ciudadela and Fornells, would be blocked.

The Mesquida force would quickly move to Mahón town to capture the Governor and British soldiers. The Alcaufar force would block the road from Georgetown (a British area) to St. Philip's Castle. A third force would land at Ciudadela to block the main road across the island. Finally, a small group would land at Fornells to take a small fort there.

The Real Invasion Day

This plan had a big problem: it assumed the British wouldn't realize a huge fleet meant an invasion. Also, strong winds forced the main fleet to sail around the south of the island instead of the north. This made the landing at Ciudadela impossible for a while.

So, around 10:30 AM, the fleet sailed around Aire Island, at Menorca's southeast tip. They began to approach Port Mahón. Around 1:00 PM, the lead ship arrived at Mesquida, and the rest of the fleet followed. At 6:00 PM, the Spanish flag was raised on the beach with a 23-gun salute.

The British had a watchtower on Menorca's south coast. They saw the fleet coming and sent an urgent message to Mahón. By midday, most British people around Mahón had moved inside St. Philip's Castle. They also blocked the port entrance with a chain and by sinking small ships. This made it impossible for enemy ships to enter by sea.

Governor Murray's family sailed to safety in Italy. A message about the invasion was sent to the British in Florence. It said the soldiers were "in high health and Spirits" and would fight hard. When Spanish troops entered Mahón town, most local people cheered them. In Georgetown, only 152 prisoners were taken. The troops sent to Ciudadela and Fornells found only about 50 British soldiers.

By August 23, there were over 7,000 Spanish soldiers on Menorca, and 3,000 more arrived soon. The main part of the fleet left once the troops were settled. When news reached Britain, newspapers said the British had about 5,660 men. But many of these were local helpers or civilians. The real number of fighting men in the fort was closer to 3,000.

The Battle Begins

The Siege of St. Philip's Castle

The Spanish and French forces quickly started building gun positions to attack St. Philip's Castle. The most important ones were at La Mola, across the harbor, and at Binisaida, near Georgetown. The British inside the castle didn't make it easy. They fired their own guns at the work sites. They also sent soldiers out of the fort to attack.

The most famous attack by the British happened on October 11. Between 400 and 700 British soldiers crossed the harbor to La Mola. They captured 80 Spanish soldiers and 8 officers. Spanish troops tried to chase them but were too late. The captured officers were later set free. Three British soldiers died in this action.

Even before this, some of de Crillon's soldiers were unhappy. They compared the siege to a failed Spanish attack on Algiers in 1775. So, more soldiers were sent to Menorca. By October 23, almost 4,000 more men had joined the 10,411 already on the island.

An Offer to Surrender

Around this time, de Crillon was asked by the Spanish government to try a different plan. He offered Governor Murray 500,000 pesos (a lot of money) and a high rank in the Spanish or French army if he surrendered. Murray refused strongly. He wrote back to de Crillon, reminding him that his family was as noble as de Crillon's. He also mentioned that a past Duc de Crillon had refused to betray his honor. De Crillon replied that he understood Murray's feelings.

The Great Bombardment

On November 11, the attacking forces began firing their large mortar cannons. At first, only a small gun carriage inside the castle was damaged. One of the attackers' mortar batteries was destroyed when a shell from the castle hit its powder storage. The castle gunners also sank a supply ship trying to unload at Georgetown.

Letters from Governor Murray reached England by December 4. They reported these events. The British government sent letters back to Murray, praising the soldiers' bravery and promising help. But with Gibraltar also under attack, Britain relied on the strong defenses of St. Philip's Castle. The fort had enough food for over a year.

After almost two months of constant firing, the final attack was set for January 6, 1782. The attackers used 100 cannons and 35 mortars. Their intense firing damaged the outer defenses so much that Murray had to pull his troops back inside the main part of the fort.

However, when the firing slowed, the defenders fired back with over 200 cannons and 40 mortars. On January 12, they sank another supply ship. Three days later, the attackers got their revenge. They used a special grenade to set fire to a key storage building. This building held much of the fort's salted meat. It burned for four days.

The British Defeat

Losing the meat was a big problem for the soldiers. The fort's improvements didn't include gardens for fresh vegetables. This meant the soldiers didn't have fresh food, which helps prevent a disease called scurvy. Scurvy is caused by not getting enough vitamins.

More and more soldiers got scurvy. By early February, over 50 new soldiers were going to the hospital every day. To guard all parts of the fort, 415 men were needed for each shift. By February 3, only 660 men could do any duties at all. This meant they were short 170 men to keep two shifts of guards going each day. Of those 660 men, 560 showed signs of scurvy. Some even died while on guard duty because they didn't report how sick they were.

On February 4, 1782, General Murray sent a list of ten surrender terms to the Duc de Crillon. He wanted his soldiers to be sent back to Britain, with Britain paying for the transport. De Crillon had to refuse this because he was told to make them prisoners of war. But he hinted that they could find a middle ground.

The final agreement was made on February 5 and signed on February 6. It allowed the men to be temporary prisoners of war while they waited for ships. It also said that because of their "Constancy and Valour" (their strength and bravery), General Murray and his men could march out with their weapons, drums playing, and flags flying. They would march through the middle of the enemy army and then lay down their arms.

About 950 men who could walk did so. Spanish and French troops lined the road from St. Philip's Castle to Georgetown. There, the British soldiers laid down their weapons. Even though Murray looked straight ahead, de Crillon told him that many French and Spanish soldiers cried at what they saw. De Crillon and his officers went beyond the agreement and helped the British soldiers recover.

What Happened Next

The Spanish newspaper Gaceta de Madrid reported that 184 Spanish soldiers were killed and 380 wounded. The London Gazette said 59 British soldiers were killed. This left 2,481 military people, including 149 wounded, to surrender. This suggests that many deaths from scurvy were not counted, or that the British had said they had more soldiers than they really did. After the surrender, 43 civilian workers, 154 wives, and 212 children also left the fort.

The castle itself was later damaged so badly that it could not be easily repaired. This was done so it couldn't be captured in a surprise attack and used against the Spanish.

After his success, the Duc de Crillon was given the title "duque de Mahón." He was then put in charge of trying to take back Gibraltar. For the result of that, see Great Siege of Gibraltar.

Lieutenant General James Murray faced a military trial in November 1782. He was found guilty of only two things. The more serious one was giving an order that was disrespectful to his deputy. In January 1783, he was given a warning. Soon after, King George III himself made his deputy apologize to Murray for some things he had said. In February, Murray was promoted to a full General. He was over 60 by then, so he never returned to active service.

Britain captured Menorca again in 1798 during the French Revolutionary Wars. But they gave it back to Spain for good in 1802 after the Treaty of Amiens.

Principal source

- Terrón Ponce, José L. "La reconquista de Menorca por el duque de Crillon (1781–1782)" Mahón, Museo Militar (1981) – accessed 2007-12-17

Further information

- Historic maps of the Port Mahon area (click compass roses) mapforum.com – accessed 2007-12-15

- 18th century pictures and more maps, menorcaprints.com – accessed 2007-12-15

- French web page about St. Philip's Castle, with good pictures, cardona-pj.net – accessed 2007-12-15

- Terrón Ponce, José L. Online versions of various articles (in Spanish) including several related to the 1781-2 siege – accessed 2007-12-17

- Terrón Ponce, José L. La toma de Menorca en las memorias y epistolario del duque de Crillon, Mahón, I.M.E. (1998)- online edition

See also

In Spanish: Toma de Menorca (1782) para niños

In Spanish: Toma de Menorca (1782) para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |