Cherry Valley massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cherry Valley massacre |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

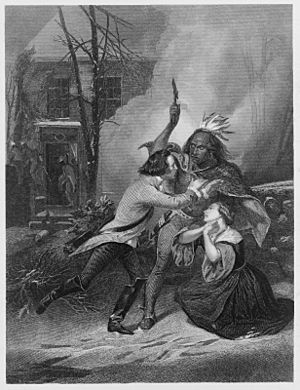

The Cherry Valley massacre, showing the fate of Jane Wells, one of thirty civilians killed during the attack. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ichabod Alden † William Stacy (POW) |

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5 wounded | ||||||

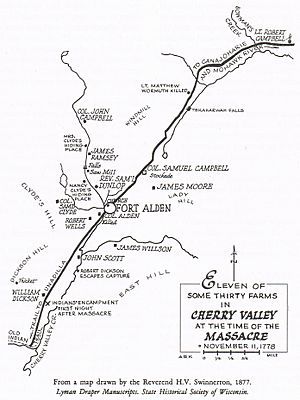

The Cherry Valley massacre was a surprise attack during the American Revolutionary War. It happened on November 11, 1778, in Cherry Valley, a small village in central New York. Forces from Britain and their Iroquois allies attacked a fort and the village.

This event is remembered as one of the most violent attacks on the frontier during the war. A group of British soldiers, colonists loyal to Britain (called Loyalists), and Native American warriors from the Seneca and Mohawk nations attacked Cherry Valley. Even though the village defenders had been warned, they were not ready for the attack. During the raid, the Seneca warriors especially targeted people who were not fighting. Reports say that 30 civilians were killed, along with several soldiers.

The overall leader of the attackers was Walter Butler. However, he had little control over the Native American warriors. Some historians say Butler's leadership was very poor. The Seneca people were angry because they had been accused of terrible acts in another battle. They were also upset because American colonists had recently destroyed their villages. Butler often said he could not stop the Seneca warriors. But some people accused him of allowing the violence to happen.

During the war in 1778, Joseph Brant, a Mohawk leader, gained a reputation for being harsh. But he was not actually at the Battle of Wyoming, where many thought he was. At Cherry Valley, he tried to stop the violence. Since Butler was the main commander, there is still debate about who was truly responsible for the killings. This attack led to calls for revenge. This resulted in the 1779 Sullivan Expedition. This expedition led to the military defeat of the Iroquois nations who had sided with the British in Upstate New York.

Contents

The Story Behind the Attack

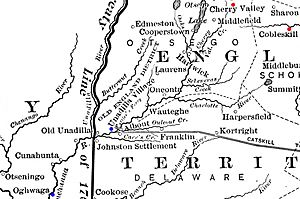

After the British lost the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777, the American Revolutionary War in upstate New York changed. It became a frontier war, fought along the edges of settled areas. The Mohawk Valley was a key target. This was because its rich soil produced many crops for the American Patriot troops.

British leaders in Quebec helped Loyalist and Native American fighters. They gave them supplies and weapons. During the winter of 1777–78, Joseph Brant and other Native Americans allied with the British made plans. They wanted to attack frontier settlements in New York and Pennsylvania.

In February 1778, Brant set up a base at Onaquaga. This is near present-day Windsor, New York. By May, he had gathered between 200 and 300 Iroquois and Loyalists. One of his goals was to get food and supplies for his forces. He also wanted to help John Butler, who was planning attacks in the Susquehanna River valley.

Brant started his campaign in late May with a raid on Cobleskill. He attacked other frontier communities throughout the summer. The local militia and American army units could not stop these raiders. The attackers usually left quickly before many defenders arrived. After Brant and some of Butler's Rangers attacked German Flatts in September, the Americans fought back. They organized a military action that destroyed the villages of Unadilla and Onaquaga in early October.

While Brant was active, Butler led a large mixed force. They attacked the Wyoming Valley in northern Pennsylvania in early July. This attack made things more complicated. The Seneca warriors in Butler's group were accused of killing civilians. Many American militia members then broke their promises not to fight. They joined a revenge attack against Tioga.

The exaggerated stories about the Seneca angered them, especially the destruction of Unadilla, Onaquaga, and Tioga. The Wyoming Valley attack, even though Brant was not there, made many people see him as a very harsh enemy.

Preparing for Battle

Brant then joined forces with Captain Walter Butler. Butler was the son of John Butler. They led two companies of Butler's Rangers. Their goal was to attack the important settlement of Cherry Valley. Butler's forces also included 300 Seneca warriors, likely led by Cornplanter or Sayenqueraghta. There were also Cayuga warriors led by Fish Carrier, and 50 British soldiers.

As they moved toward Cherry Valley, Butler and Brant had an argument. Butler was unhappy that Brant had recruited many Loyalists. He threatened to stop giving supplies to Brant's Loyalist volunteers. Ninety of them ended up leaving the group. Brant himself almost left, but his Native American supporters convinced him to stay. This disagreement upset the Native American forces. It may have weakened Butler's control over them.

The Attack Begins

Cherry Valley had a fort surrounded by a wooden fence (called a palisade). This fort was built after Brant's raid on Cobleskill. It was defended by 300 soldiers from the 7th Massachusetts Regiment of the American army. Their commander was Colonel Ichabod Alden.

By November 8, Alden and his officers knew the Butler–Brant force was coming. They had been warned by Oneida spies. However, Alden did not take basic safety steps. He continued to stay at a house belonging to a settler named Wells. This house was about 400 meters (400 yards) away from the fort.

Butler's force arrived near Cherry Valley late on November 10. They set up a quiet camp to avoid being seen. They scouted the town and found the weaknesses in Alden's setup. The attackers decided to send one group to Alden's house and another to the fort. That night, Butler made the Native American warriors promise not to harm civilians.

The attack started early on the morning of November 11. Some eager Native American warriors ruined the surprise. They fired at settlers who were cutting wood nearby. One settler escaped and raised the alarm. Little Beard led some Seneca warriors to surround the Wells house. The main group surrounded the fort.

The attackers killed at least sixteen officers and soldiers guarding the house, including Colonel Alden. Lt. Col. William Stacy, the second-in-command, was also staying at the Wells house and was captured. Stacy's son Benjamin and cousin Rufus Stacy ran through gunfire to reach the fort from the house. Stacy's brother-in-law, Gideon Day, was killed. Those attacking the Wells house eventually got inside. There was hand-to-hand fighting. After killing most of the soldiers there, the Seneca warriors killed everyone in the Wells household, twelve people in total.

Inside the Fort and Village

The attackers' attempt to take the fort failed. They did not have heavy weapons, so they could not break through its strong wooden walls. Loyalists then guarded the fort. Meanwhile, the Native American warriors went through the rest of the settlement. They were seeking revenge. Not a single house was left standing. Reports said the Seneca warriors killed anyone they met.

Butler and Brant tried to stop the violence, but they were not successful. Brant was especially upset. He learned that several families he knew well and considered friends had suffered greatly. These included the Wells, Campbell, Dunlop, and Clyde families.

Lt. William McKendry, a supply officer in Colonel Alden's regiment, wrote about the attack in his journal: "Immediately came on 442 Indians from the Five Nations, 200 Tories under the command of one Col. Butler and Capt. Brant; attacked headquarters; killed Col. Alden; took Col. Stacy prisoner; attacked Fort Alden; after three hours retreated without success of taking the fort."

McKendry listed the people killed in the attack. These included Colonel Alden, thirteen other soldiers, and thirty civilians. Most of the soldiers who died had been at the Wells house.

Stories about Lt. Col. Stacy's capture say he was about to be killed. But Brant stepped in and saved him. It is said Stacy was a Freemason. He appealed to Brant as a fellow Freemason, and his life was spared.

What Happened Next?

The next morning, Butler sent Brant and some rangers back into the village. They finished destroying it. The attackers took 70 people captive, many of them women and children. Butler managed to get about 40 of these captives released. But the rest were kept in their captors' villages until they could be exchanged for other prisoners. Lt. Col. Stacy was taken to Fort Niagara as a prisoner of the British.

A Mohawk chief explained the attack at Cherry Valley in a letter to an American officer. He wrote that the Americans "Burned our Houses, which makes us and our Brothers, the Seneca Indians angrey, so that we destroyed, men, women and Children at Chervalle." The Seneca also said they would "no more be falsely accused, or fight the Enemy twice." This meant they would not show mercy in the future.

Butler reported that "despite my best efforts to save the Women and Children, I could not prevent some of them from becoming sad victims to the Fury of the Savages." He also said he spent most of his time guarding the fort during the raid. Quebec's Governor Frederick Haldimand was very upset that Butler could not control his forces. He refused to meet with Butler. He wrote that "such widespread revenge, even against the tricky and cruel enemy they are fighting, is useless and brings shame to them."

Butler continued to insist in later writings that he was not to blame for what happened that day.

The violent frontier war of 1778 led to calls for the American army to take action. The Cherry Valley attack, along with accusations of civilian killings at Wyoming, helped lead to the Sullivan Expedition in 1779. This expedition was ordered by commander-in-chief Major General George Washington. It was led by Major General John Sullivan. The expedition destroyed over 40 Iroquois villages in their homelands in central and western New York. It forced women and children into refugee camps at Fort Niagara. However, it did not stop the frontier war, which continued with new intensity in 1780.

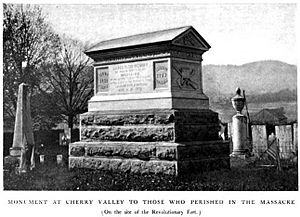

Remembering the Event

A monument was built at Cherry Valley. It was dedicated on August 15, 1878, for the 100th anniversary of the attack. Former New York Governor Horatio Seymour gave a speech at the monument. About 10,000 people were there. He spoke about honoring the people who died and thanking their descendants. He hoped their example would inspire others. He urged everyone to remember the sacrifice made by the people of Cherry Valley.

Years after the attack, Benjamin Stacy's home village of New Salem, Massachusetts, started a tradition. They celebrated their annual Old Home Day holiday with a Benjamin Stacy footrace. This race honored his escape at Cherry Valley.