Recruitment in the British Army facts for kids

The British Army was formed in 1707 when the Kingdoms of England and Scotland joined to create Great Britain. It brought together army groups that already existed in both England and Scotland. For most of its history, the British Army has relied on people who choose to join, called volunteers. The only times people were forced to join (this is called conscription) were during the latter part of the First World War until 1919, and again during the Second World War. Conscription stopped in 1960.

Contents

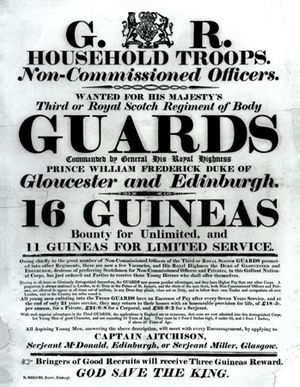

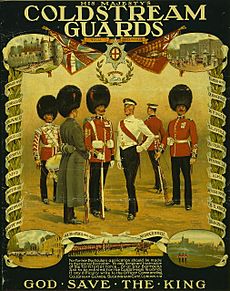

Early Days: 1700s and 1800s

At the start of the 1700s, the British Army was quite small. It had about 7,000 soldiers at home and 14,000 overseas. Soldiers could join between the ages of 17 and 50. The government kept the army small during peacetime. This was because they worried the King or Queen might use a large army to take too much power. The Bill of Rights of 1689 made it clear that Parliament had to agree to have a standing army when there wasn't a war.

For much of the 1700s, the army found soldiers in many ways. They also hired soldiers from other countries in Europe, like Danes and Hessians. By 1709, during the War of the Spanish Succession, the British forces had grown to 150,000 men. A large number of these were foreign soldiers. The rest were from the British Isles, mostly from poorer families. Each army group, called a regiment, was in charge of finding its own soldiers. Officers would travel to towns and villages to recruit. Sometimes, the government even allowed people to force vagrants (homeless people) to join.

Joining the army was not very popular because of low pay and harsh punishments like flogging. During the American Revolutionary War, laws were passed in 1778 and 1779 to force people to join. Many men volunteered to avoid being forced. Some even cut off their thumb and forefinger to avoid serving! These laws were stopped in 1780. The government also let criminals and people who owed money out of prison if they joined the army. After the war, the British Army became very small and its spirit was low. By 1793, it had only 40,000 men.

The Napoleonic Wars

The fight against France during the Napoleonic wars meant the British Army needed many more soldiers, quickly. Normal ways of finding recruits were not enough. The army tried different methods, like asking communities to provide soldiers. Some generals even wanted to force people to join, but this never happened for the regular army. It was hard to find soldiers because many young men were working in new factories, earning more money than soldiers.

A soldier's pay was very low. In 1806, a private earned 7 shillings a week, while a dockworker could earn 28 shillings. Soldiers hoped to get more money from promotions or from things they found during campaigns. Joining the army often meant serving for life, which could be very short. For example, many soldiers sent to the Caribbean in the 1790s died from disease. The army struggled to replace soldiers who were discharged, wounded, or killed. In 1794 alone, over 18,000 soldiers died. The British Army also used foreign volunteers, like Germans and Greeks. By 1813, about one-fifth of the army (52,000 men) were foreign volunteers. The British Army had over 250,000 men in 1813. This was much bigger than before, but still smaller than France's army, which had over 2.6 million men because they used conscription.

Making the Army Better

From 1798, the Duke of York, who was in charge of the army, started making important changes. These changes slowly made life better for the average soldier. He worked to stop corruption and reduced harsh physical punishments for small mistakes. He also made it harder for officers to buy their promotions. Officers now had to serve for a certain number of years before they could be promoted.

The Royal Military Academy was set up to train officers. Regular soldiers could now join for a limited time, not just for life. Officers like Sir John Moore tried to build better relationships with their soldiers. They motivated troops through respect and rewards, not just punishment. New training methods, like the Shorncliffe System for light infantry, taught soldiers to think for themselves. These changes helped the British Army win battles in places like the Peninsula and at Waterloo.

After the Napoleonic Wars

After winning the Napoleonic Wars, Europe had 40 years of peace. The army that had won the war was largely forgotten. The government wanted to cut taxes, so they cut the army's budget a lot. The budget went from £43 million in 1815 to just £8 million in 1836. With less money, the number of soldiers also dropped. In 1815, there were over 233,000 men, but by 1838, there were only about 91,000.

Changes in the 1870s

The army stayed small during peacetime. Big changes only happened in the 1870s with the Cardwell reforms. The Crimean War showed that the army had many problems. Even though there were supposed to be 70,000 soldiers in Britain, many were too old, sick, or just passing through. This meant Britain had very few trained soldiers to send to the Crimea.

The Cardwell reforms made several improvements. They stopped officers from buying their ranks, which meant promotions were based on skill. They also banned flogging and made service shorter to attract more recruits. A new law changed how people joined, creating trained reserve soldiers and making the army a more attractive job. A "Localization Scheme" paired up regiments with local areas, helping with recruitment and organization.

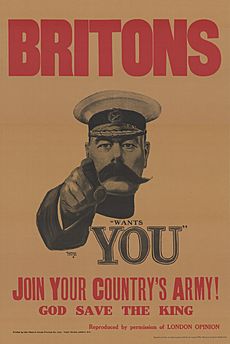

First World War Recruitment

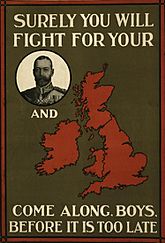

At the start of 1914, the British Army had about 710,000 men, including reserves. When war was declared in August 1914, Lord Kitchener led a huge effort to get people to join.

Young Britons eagerly joined the army for their "King and Country." By early 1915, many regular soldiers had been killed. They were replaced by part-time volunteers from the Territorial Force and Kitchener's new volunteer army. A special feature was the Pals battalions, where men from the same town or even factory could serve together. Kitchener's campaign was very successful. On September 1, 1914, over 30,000 men joined. Thousands more wanted to enlist every day. However, the government soon realized a problem: many skilled workers were leaving their jobs to join, which hurt the war effort. A more controlled way of enlisting was needed.

The Military Service Bill became law in January 1916. It said that men aged 18 to 41 had to join the army. There were exceptions for married men, widowers with children, or those in certain important jobs. By the end of World War I, almost a quarter of all men in the UK, over five million, had joined the army.

Between the World Wars (1919–1938)

After World War I, the army was made much smaller. By 1920, it had only 370,000 soldiers. The new Royal Air Force could patrol large areas and police the British Empire more cheaply from the sky. The army's budget was cut every year. During the Great Depression in 1932, it was less than £36 million. Only when Germany became a threat did the budget increase again. By 1938, it was £123 million, and the army started recruiting quickly once more.

Second World War Recruitment

Before World War II, the army was all-volunteer. Recruits usually joined the part of the army they wanted. They had a quick interview, a medical check, and some basic tests. If they passed, they were sent to their chosen branch. There wasn't a scientific way to choose who went where, unlike in the German army. This meant some men ended up in jobs they weren weren't suited for. The army also lacked enough skilled workers and tradesmen needed for modern warfare.

In 1941, the Beveridge committee looked into this problem. Their findings in 1942 led to the creation of the General Service Corps. This helped make sure skilled men were placed in the right jobs. In early 1939, the government finally allowed conscription to prepare for the threat from Germany. The Military Training Act of April 27, 1939, required all men aged 20 and 21 to have six months of military training. When the war started, this act was expanded to include all fit men aged 18 to 41. Conscription was slowly brought in, starting in October 1939.

At the start of World War II, the British Army had 897,000 men. By the end of 1939, it had 1.1 million men. By June 1940, this number grew to 1.65 million. By the end of the war, about 2.9 million men had served in the British Army. The Local Defence Volunteers, later called the "Home Guard," was also formed. Many civilians who were too old or too young for the regular army joined to help defend Britain from a possible German invasion.

After the War

After World War II, conscription ended, and the army became smaller again. It went back to its job of looking after the British Empire. In 1947, British India became independent. This meant the British Army lost the British Indian Army, which had thousands of volunteer soldiers. Without this large army, the regular British Army was too small for the demands of the upcoming Cold War and maintaining the Empire.

To meet these needs, the government brought back peacetime conscription with the National Service Act in 1947. This period of peacetime conscription is usually called 'National Service' in the UK. Most National Servicemen joined the Army. By 1951, they made up half of the army. The last group of National Servicemen joined in 1960, and the last one left the army in 1963. After that, the army went back to being an all-volunteer force, which it still is today.

The decision to end National Service was made in 1957. This led to a huge drop in the number of soldiers, from about 330,000 to 165,000 by 1963. The army continued to get smaller in the following decades. Between 1963 and 1992, its strength dropped to 153,000. After the Cold War ended, a review in 1992 cut the army by another 50,000 soldiers.

The British Army Today

The British Army currently has about 102,000 regular soldiers. It mostly recruits people from the United Kingdom. It usually aims to get around 25,000 new soldiers each year. When there are not many people looking for jobs in Britain, the army sometimes finds it hard to meet this goal. In the early 2000s, more people from Commonwealth countries started joining.

You can join the army at 16 years old, after finishing your GCSEs. However, soldiers cannot serve in active operations until they are 18. As of November 2018, you can join as a regular soldier up to 35 years and 6 months old. For reserve soldiers, the maximum age is 49. If you want to become an officer, the maximum age is 29. Soldiers usually sign up for 22 years. Once you join, you usually cannot leave until you have served at least four years. Soldiers now sign up for a 24-year period called "versatile engagement." After 22 years, a soldier might be offered a 2-year extension, and then more extensions until they are 55.

Officers and Royalty

Before the late 1700s, British Army officers mostly came from rich families or families with a history of military service. This was different from the Navy, where officers often came from middle-class backgrounds. Prince Frederick, the son of King George III, did a lot to improve the quality of officers when he was in charge of the army from 1795 to 1827. The practice of officers buying their ranks was finally stopped by the Cardwell reforms in the 1870s. Even after this, officers often still came from more privileged backgrounds than regular soldiers.

Members of the Royal Family have traditionally served in the Armed Forces, often in the Royal Navy, but many have also served in the Army. This tradition continues today, with Prince Harry and Prince William both joining the Army as officers. Royals are no longer kept out of danger. Prince Harry served in Afghanistan, and Prince Andrew was a helicopter pilot in the Royal Navy during the Falklands War.

Some foreign royals have also served in the British Army. For example, Eugène Bonaparte, the son of Napoléon III, joined the Royal Artillery but was killed in South Africa in 1879 during the Anglo-Zulu War. Later, King Abdullah II of Jordan served as an officer, and Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said of Oman also served in the army.

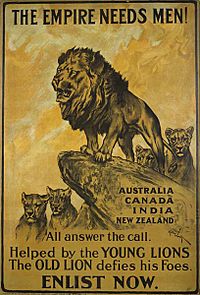

Recruiting from the Empire and Commonwealth

During both World Wars, people from all over the British Empire volunteered to help the United Kingdom. In World War I, countries like Canada, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand raised their own armies. These armies were part of the British fighting forces. Over 2.5 million men from the Empire volunteered.

In peacetime, soldiers from the British Empire usually joined local regiments to protect their own lands. This meant the British Army didn't have to send as many of its own units there. One of the oldest regiments from the Empire was the West India Regiment, formed in 1795. Its soldiers were originally freed slaves or slaves bought in the West Indies. This regiment was part of the regular British Army until it was disbanded in 1927.

The British Indian Army

The largest colonial army was the British Indian Army. Until India became independent, this was a volunteer army made up of local people, with British officers. The Indian Army helped keep peace in India and fought in other parts of the world during the World Wars. It was a very important part of the British forces. About 1.3 million men served in World War I, and 2.5 million in World War II. At first, only the officers were British, but later, Indian officers were also promoted.

Gurkhas

Gurkhas have been part of the Indian Army since the early 1800s. After India became independent, some Gurkha units joined the British Army. Today, about 3,500 Gurkhas serve in the British Army. Joining the British Army is one of the few ways for Nepalese people to escape poverty and earn a good salary. Because of this, thousands apply each year. In 2007, over 17,000 people applied for just 230 jobs. Since 2010, women have also been allowed to join. Candidates must be between 17 and a half and 21 years old.

Irish Regiments

Many Irishmen have served in the British Army since the late 1700s, including during the Napoleonic Wars. At one point, 20 to 40 percent of British soldiers were Irish-born. Even though recruitment numbers dropped after the Irish Famine, Irish people were still a big part of the army compared to their population size. By the early 1900s, fewer Irish people volunteered as Irish nationalists criticized joining the British Army.

Over 28,000 Irishmen served in the Second Boer War. By 1910, Irish recruitment fell to 9 percent. During World War I, over 200,000 Irish soldiers volunteered. In World War II, over 70,000 were recruited from the Republic of Ireland and 38,000 from Northern Ireland.

The writer Rudyard Kipling, whose son died serving in World War I, wrote about the importance of the Irish in the British Army:

For where there are Irish there's bound to be fighting,

And when there's no fighting it's Ireland no more.

Commonwealth and Foreign Recruitment Today

Until 1998, there were rules about people from Commonwealth countries joining the British Army. Generally, they had to live in the UK for five years first. In 1998, these rules were lifted because the army was having trouble finding enough British recruits. Many Commonwealth citizens then joined.

The Ministry of Defence later put a limit on recruits from Commonwealth countries: no more than 10% of any army group. This didn't affect the Gurkhas. Some people worried that too many foreign soldiers would make the army less "British."

In 2008, about 6.7% of the army's total strength were volunteers from Commonwealth countries (not including Gurkhas). In total, 6,600 foreign soldiers from 42 countries served. After Nepal, the country with the most citizens in the British Army was Fiji (1,900), followed by Jamaica and Ghana. Soldiers also came from wealthier countries like Australia and New Zealand. People from the Republic of Ireland also join, and their numbers have been increasing.

In 2013, the old rules were brought back. Most Commonwealth citizens had to live in the UK for five years before joining. However, as of May 2016, Commonwealth citizens can join the British Army in some roles without meeting the residence rules. On November 5, 2018, the five-year residence rule was removed again. This meant any Commonwealth citizen could join the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy from November 6, 2018. The British Army planned to open applications in early 2019.

|

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |