Battle of Rhode Island facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Rhode Island |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

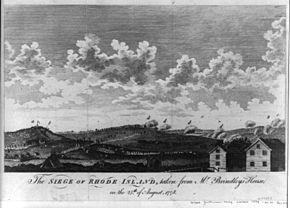

A 1779 print depicting the battle |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Sullivan Nathanael Greene Christopher Greene Comte d'Estaing |

Sir Robert Pigot Francis Smith Richard Prescott Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,100 | 6,700 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 30 killed 137 wounded 44 missing |

38 killed 210 wounded 12 missing |

||||||

The Battle of Rhode Island happened on August 29, 1778. It was a fight during the American Revolutionary War. American soldiers and local fighters, led by General John Sullivan, were trying to capture the British-held town of Newport, Rhode Island. Newport is on Aquidneck Island.

The Americans had been trying to surround the British forces. But they had to stop their attack and move back to the northern part of the island. The British then attacked the retreating Americans. The battle ended without a clear winner, but the Americans left Aquidneck Island. This meant the British kept control of it.

This battle was the first time French and American forces worked together. France had recently joined the war as an American ally. Plans to attack Newport were made with a French fleet and soldiers. However, problems between the commanders and a big storm caused issues. The storm damaged both the French and British fleets just before the attack.

The battle is also remembered for the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. This group was led by Colonel Christopher Greene. It was made up of African Americans, Native Americans, and white colonists fighting together.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened: The Background

On December 8, 1776, British General Henry Clinton led an attack. His goal was to take control of Rhode Island. British soldiers, including some German soldiers called Hessians, landed and took over Newport.

In February 1778, France officially recognized the United States. This happened after the British Army surrendered at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777. France then declared war on Great Britain in March 1778.

French Help Arrives

France sent Admiral Comte d'Estaing with a large fleet. He had 12 big warships and 4,000 French soldiers. Their first mission was to block the British fleet in the Delaware River.

British leaders knew d'Estaing was coming to North America. But arguments within their government and navy delayed their response. So, d'Estaing sailed without trouble. A British fleet of 13 warships left Europe in June to chase him. This fleet was led by Admiral John Byron.

D'Estaing's journey across the Atlantic took three months. Byron's fleet was also delayed by bad weather. He didn't reach New York until mid-August.

The British had already left Philadelphia and moved to New York City. So, d'Estaing's fleet arrived at Delaware Bay in July, but the British ships were gone. D'Estaing decided to sail to New York. However, New York's harbor was very well defended. French and American pilots thought d'Estaing's biggest ships couldn't get into the harbor.

So, French and American leaders decided to attack British-occupied Newport, Rhode Island instead. While d'Estaing was outside New York, British General Sir Henry Clinton sent 2,000 more troops to Newport. These troops arrived on July 15. This made Major General Robert Pigot's force in Newport more than 6,700 men.

American Forces Prepare

American and British forces had been facing each other on Aquidneck Island since late 1776. In March 1778, Congress chose Major General John Sullivan to lead the American forces in Rhode Island. By May, Sullivan was ready to plan an attack on Newport. He started gathering supplies.

British General Pigot knew about Sullivan's plans. On May 25, he sent a raid to Bristol and Warren. They destroyed military supplies and took things from the towns. Sullivan asked for more help.

General George Washington told Sullivan on July 17 to gather 5,000 troops for Newport. Sullivan got this message on July 23. The next day, Colonel John Laurens arrived. He confirmed that Newport was the target. Sullivan's force at that time was only 1,600 troops. Laurens came ahead of more Continental troops led by the Marquis de Lafayette.

News of French involvement made many people want to help. Local fighters, called militia, came from nearby states. Half of Rhode Island's militia joined. Many militia from Massachusetts and New Hampshire also came. Washington sent Major General Nathanael Greene, a reliable officer from Rhode Island, to help Sullivan. Washington told Sullivan to listen to Greene and Lafayette.

Getting Ready for Battle: The Prelude

French Ships Arrive at Newport

D'Estaing sailed from New York on July 22. He headed towards Newport. The British fleet in New York, led by Lord Richard Howe, followed him. D'Estaing arrived near Point Judith on July 29. He met with Generals Greene and Lafayette to plan the attack.

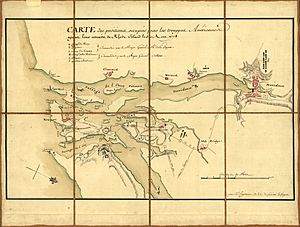

Sullivan suggested that the Americans cross to Aquidneck Island from Tiverton. French troops would use Conanicut Island as a starting point. They would cross from the west. This would cut off British soldiers at Butts Hill on the northern part of the island.

The next day, d'Estaing sent smaller ships into the Sakonnet River and the main channel to Newport. As the allied plans became clear, General Pigot moved his forces to defend Newport. He pulled troops back from Conanicut Island and Butts Hill. He also moved all animals into the city. He destroyed orchards for clear firing lines and broke wagons. French ships forced some British support ships to run aground. These were burned to prevent capture. On August 8, d'Estaing moved most of his fleet into Newport Harbor.

On August 9, d'Estaing began landing some of his 4,000 troops on Conanicut Island. That same day, General Sullivan learned that Pigot had left Butts Hill. Sullivan quickly moved his troops to take this high ground. He was worried the British might take it back. D'Estaing later agreed with this action. But at first, he and some of his officers were unhappy.

A Big Storm Hits

Lord Howe's fleet was delayed leaving New York by bad winds. He arrived near Point Judith on August 9. D'Estaing worried that Howe would get more ships and have more power. So, he put his French troops back on their ships and sailed out to fight Howe on August 10.

But the weather got much worse. A big storm, called a nor'easter, hit as the two fleets prepared to fight. The storm lasted two days and scattered both fleets. It badly damaged the French flagship. This storm also ruined Sullivan's plans to attack Newport without French help on August 11. Sullivan started to surround the British lines. He moved closer to the British on August 15 and dug trenches the next day.

As the two fleets tried to regroup, individual ships met each other. There were a few small naval fights. Two French ships, already damaged by the storm, were badly hit. D'Estaing's flagship was one of them. The French fleet regrouped near Delaware. They returned to Newport on August 20. The British fleet regrouped in New York.

French Leave for Boston

Admiral d'Estaing's captains pressured him to sail to Boston for repairs. But he first sailed to Newport to tell the Americans he couldn't help them. He told Sullivan on August 20. Sullivan argued that the British could surrender in just a day or two if the French stayed. But d'Estaing refused. He wrote that it was hard to believe 6,000 well-defended men could be defeated so quickly. D'Estaing's captains also opposed staying at Newport.

The French decision made many American soldiers and commanders angry. General Sullivan used strong words, calling d'Estaing's decision "dishonorable to France." American soldiers called the French departure a "desertion."

The French leaving caused many American militia to go home. Many had only signed up for 20 days anyway. On August 24, Sullivan learned that Clinton in New York was gathering more troops to help the British. That evening, Sullivan's leaders decided to pull back to the northern part of the island. Sullivan still tried to get French help. He sent Lafayette to Boston to talk with d'Estaing. But it didn't work.

Meanwhile, the British in New York had been busy. Lord Howe got more ships. He sailed out to catch d'Estaing before he reached Boston. General Clinton gathered 4,000 men under Major General Charles Grey. They sailed for Newport on August 26.

The Battle Begins

On the morning of August 28, the American leaders decided to pull their last troops from their camps. They had been firing cannons at the British for a few days. British deserters had told General Pigot about the American plans to leave on August 26. So, he was ready when they left that night.

The American generals set up a defensive line across the island. It was just south of a valley that cut across the island. They hoped to keep the British from taking the high ground in the north. They organized their forces into two parts:

- On the west, General Greene put his forces in front of Turkey Hill. He sent the 1st Rhode Island Regiment to advanced positions a half-mile south.

- On the east, Brigadier General John Glover placed his forces behind a stone wall. This wall overlooked Quaker Hill.

The British attacked in a similar way. They sent German General Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg up the west road. Major General Francis Smith went up the east road. Each had two regiments. They were told not to start a full attack. But this advance led to the main battle.

Smith Attacks the American Left

Smith's advance stopped when it came under fire from troops led by Lt. Col. Henry Brockholst Livingston. Livingston was at a windmill near Quaker Hill. Pigot sent more troops to help Smith. With these extra soldiers, Smith attacked again. He sent his regiments against Livingston's left side. Livingston also got more troops from Sullivan. But he was still pushed back to Quaker Hill.

Then, a German regiment threatened to go around Quaker Hill. Livingston and his men left the hill and went back to Glover's lines. Smith tried a small attack but was pushed back by Glover's troops. Smith saw how strong the American position was and decided not to launch a major attack. This ended the fighting on the American left side.

Lossberg Attacks the American Right

By 7:30 a.m., Lossberg had moved against the American Light Corps. These troops were led by Col. John Laurens. They were behind stone walls south of the Redwood House. Lossberg pushed Laurens' men back onto Turkey Hill. Laurens got more troops from Sullivan. But Lossberg stormed Turkey Hill and pushed the defenders back to Nathanael Greene's part of the army. Then, Lossberg started firing cannons at Greene's lines.

By 10 a.m., three British ships started firing at Greene's troops on the American right side. Lossberg then attacked Greene. German troops attacked Major Ward's Rhode Island Colored Regiment. But they were pushed back. Meanwhile, Greene's cannons and an American battery fired at the three British ships. They drove them away.

At 2 p.m., Lossberg attacked Greene's positions again but failed. Greene counterattacked with several regiments. Greene sent his 1,500 men forward to try to go around Lossberg's right side. Lossberg was greatly outnumbered. He pulled back to the top of Turkey Hill. By 3 p.m., Greene's men were holding a stone wall. Towards evening, an attempt was made to cut off the German soldiers on Lossberg's left side. But the German and Loyalist troops pushed Greene's men away. This ended the battle. Some cannon fire continued through the night. The British had 260 casualties, with 128 of them being German soldiers.

What Happened Next: The Aftermath

The American forces moved back to Bristol and Tiverton on the night of August 30. This left Rhode Island (Aquidneck Island) under British control. However, their retreat was organized and not rushed. They didn't leave behind any supplies or equipment.

General Sullivan's angry writings reached Boston before the French fleet. Admiral d'Estaing was reportedly silent at first. Politicians worked to calm things down. Washington and the Continental Congress pushed for peace. D'Estaing was in good spirits when Lafayette arrived in Boston. He even offered to march troops overland to help the Americans.

The British relief force, led by Clinton and Grey, arrived at Newport on September 1. Since the threat was over, Clinton told Grey to raid several towns on the Massachusetts coast. Admiral Howe couldn't catch d'Estaing. D'Estaing was in a strong position in Boston Harbor when Howe arrived on August 30. Admiral Byron took over from Howe in September. But he also failed to block d'Estaing. His fleet was scattered by a storm near Boston. After that, d'Estaing sailed away to the West Indies.

General Pigot was criticized by Clinton for not waiting for the relief force. If he had waited, the Americans might have been trapped on the island. Pigot left Newport for England soon after. The British left Newport in October 1779. The war had ruined the local economy.

Places to Remember: Legacy

The Battle of Rhode Island Site was named a National Historic Landmark in 1974. It is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It protects some of the land where the battle was fought.

Also listed is the underwater site of HMS Cerberus and HMS Lark. These were two British Navy ships sunk during the French fleet's advance on Newport. Fort Barton is also listed. It was an American defense in Tiverton. The Conanicut Battery is an earthworks on Conanicut Island. It was built in 1775 and made stronger by the British. The British left it after the French fleet arrived.

The Joseph Reynolds House in Bristol was used by General Lafayette as his headquarters. It is a National Historic Landmark and one of Rhode Island's oldest buildings.

Who Fought: Order of Battle

British Forces

|

Continental Forces

|

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |