John Laurens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Laurens

|

|

|---|---|

A 1780 miniature portrait of Laurens, by Charles Willson Peale

|

|

| Born | October 28, 1754 Charleston, South Carolina, British America (now Charleston, South Carolina, U.S.) |

| Died | August 27, 1782 (aged 27) Combahee River, near Beaufort, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1777–1782 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War

|

| Spouse(s) | Martha Manning (m. 1776; died 1781) |

| Children | Frances Eleanor Laurens (b. 1777) |

| Relations |

|

| Signature | |

John Laurens (October 28, 1754 – August 27, 1782) was an American soldier and leader from South Carolina during the American Revolutionary War. He is remembered for speaking out against slavery and trying to get enslaved people to fight for their freedom as American soldiers.

In 1779, Laurens got permission from the Continental Congress for his idea to create a group of 3,000 enslaved people. They would be promised freedom if they fought in the war. However, this plan was stopped by political leaders in South Carolina. Laurens was killed in the Battle of the Combahee River in August 1782.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Laurens was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on October 28, 1754. His parents, Henry Laurens and Eleanor Ball Laurens, were wealthy planters who grew rice. His father, Henry Laurens, was a very successful businessman.

John was the oldest of five children who lived past infancy. John and his two younger brothers, Henry Jr. and James, were taught at home. After their mother died, their father took them to England for their schooling. His two sisters, Martha and Mary, stayed with an uncle in Charleston.

In October 1771, John's father moved with his sons to London. John studied in Europe from age 16 to 22. For two years, starting in June 1772, he and one brother went to school in Geneva, Switzerland. They lived with a family friend there.

When he was young, Laurens was very interested in science and medicine. But when he returned to London in August 1774, he agreed to his father's wish that he study law. In November 1774, Laurens began his law studies at the Middle Temple. His father went back to Charleston, leaving John to look after his brothers, who were still in British schools.

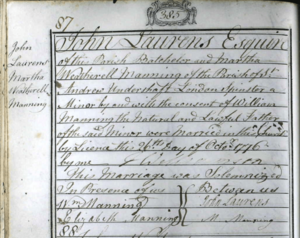

On October 26, 1776, Laurens married Martha Manning. She was the daughter of a family friend and mentor. Laurens's brother-in-law was William Manning, who became Governor of the Bank of England.

Laurens was determined to join the Continental Army and fight for his country. He did not want to finish law school in England or raise a family there. He sailed for Charleston in December 1776, leaving his pregnant wife in London with her family. In 1780, Laurens became a member of the American Philosophical Society.

Military Career and Diplomatic Missions

Serving George Washington

Laurens arrived in Charleston in April 1777. That summer, he went with his father from Charleston to Philadelphia. His father was going to serve in the Continental Congress. Henry Laurens could not stop his son from joining the Continental Army. So, he used his influence to help his 23-year-old son get an important position.

General George Washington asked Laurens to join his staff in early August as a volunteer aide-de-camp. An aide-de-camp is like a personal assistant to a general.

Laurens became close friends with two other aides, Alexander Hamilton and the Marquis de Lafayette. He quickly became known for his bravery. He first saw combat on September 11, 1777, at the Battle of Brandywine.

Two days after the Battle of Germantown, on October 6, 1777, he was officially appointed as one of General Washington's aides-de-camp. He was given the rank of lieutenant colonel. From November 2 to December 11, 1777, Washington and some aides, including Laurens, stayed at the Emlen House. This house served as Washington's headquarters during the Battle of White Marsh.

After spending the winter of 1777–1778 at Valley Forge, Laurens marched to New Jersey. He went with the rest of the Continental Army in June 1778 to fight the British at the Battle of Monmouth. Early in the battle, Laurens's horse was shot from under him while he was scouting for Baron von Steuben.

On December 23, 1778, Laurens fought a duel with General Charles Lee near Philadelphia. Laurens was offended by Lee's insults about Washington. Lee was wounded in the side by Laurens's first shot. The duel ended before either man could fire a second shot.

Fighting Against Slavery

As the British increased their operations in the South, Laurens pushed for a new idea. He wanted to arm enslaved people and offer them freedom if they served in the army. He wrote, "We Americans... cannot contend with a good Grace, for Liberty, until we shall have freed our Slaves." Laurens was different from other leaders in South Carolina. He believed that black and white people were similar and deserved freedom in a free society.

In early 1778, Laurens suggested to his father, who was then the President of the Continental Congress, that they use forty enslaved people he would inherit as part of a fighting group. Henry Laurens agreed, but with some doubts that delayed the plan.

Congress approved the idea of a regiment (a military unit) of enslaved people in March 1779. They sent Laurens south to recruit 3,000 black soldiers. However, many people opposed the plan, and Laurens was not successful. Laurens was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives. He introduced his plan for a black regiment in 1779, again in 1780, and a third time in 1782. Each time, it was strongly rejected. Governor John Rutledge and General Christopher Gadsden were among those who opposed it.

Battles in South Carolina

In 1779, when the British threatened Charleston, Governor Rutledge suggested surrendering the city. He wanted Carolina to remain neutral in the war. Laurens strongly disagreed with this idea. He fought with Continental forces to push back the British.

Battle of Coosawhatchie

On May 3, 1779, Colonel William Moultrie's troops were outnumbered two to one. They faced 2,400 British soldiers under General Augustine Prévost. The British had crossed the Savannah River. About two miles east of the Coosawhatchie River, Moultrie had left 100 men to guard a river crossing and warn them when the British arrived.

Because of Laurens's importance, his actions were noticed. For example, in a letter on May 5, South Carolina's lieutenant governor Thomas Bee wrote: "Col. John Laurens received a slight wound in the arm in a skirmish with the enemy's advanced party yesterday, & his horse was shot also – he is in a good way – pray let his father know this."

Battles of Savannah and Charleston

That fall, Laurens led an infantry regiment in General Benjamin Lincoln's attack on Savannah, Georgia. This attack was not successful.

Prisoner of War

Laurens was captured by the British in May 1780, after Charleston fell. As a prisoner of war, he was sent to Philadelphia. He was released on the condition that he would not leave Pennsylvania.

In Philadelphia, Laurens was able to visit his father. His father was about to sail to the Netherlands as an American ambassador to get loans. During the trip, Henry Laurens's ship was captured by the British. This led to the elder Laurens being imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Washington supported Laurens's desire to return to the South, saying, "The reasons which led you to the South are too good and too important not to have my approval."

Diplomatic Mission to France

After his release, Congress unwillingly appointed Laurens in December 1780 as a special minister to France. He wanted to return to the South and fight. He first refused the job and suggested Alexander Hamilton would be better. But both Hamilton and Congress convinced Laurens to accept the role. He wrote to Washington that "unfortunately for America, Col. Hamilton was not well known enough to Congress to get their votes... and I was told there was no other choice but for me to accept or the mission would completely fail."

In March 1781, Laurens and Thomas Paine arrived in France. They were there to help Benjamin Franklin, who had been the American minister in Paris since 1777. Together, they met with King Louis XVI and others. Laurens got promises from the French that their ships would help American operations that year. This naval support later proved very important at the Siege of Yorktown.

Laurens also reportedly told the French that without help for the Revolution, the Americans might be forced by the British to fight against France. When Laurens and Paine returned to America in August 1781, they brought 2.5 million livres in silver. This was the first part of a French gift of 6 million and a loan of 10 million.

Laurens also arranged a loan and supplies from the Dutch before returning home. His father, Henry Laurens, who was the American ambassador to the Netherlands, had been captured by the British. He was later exchanged for General Cornwallis in late 1781. The elder Laurens then went to the Netherlands to continue loan negotiations.

British Surrender at Yorktown

Laurens returned from France just in time to see the French fleet arrive. He joined Washington in Virginia at the siege of Yorktown. He was given command of a group of light infantry soldiers on October 1, 1781, after their commander was killed. Laurens, under the command of Colonel Alexander Hamilton, led his group in attacking Redoubt No. 10.

British troops surrendered on October 17, 1781. Washington chose Laurens to be the American representative for writing the official terms of the British surrender. Louis-Marie, Vicomte de Noailles, a relative of Lafayette's wife, was chosen by Rochambeau to represent France. At Moore House on October 18, 1781, Laurens and the French representative discussed terms with two British representatives. The surrender documents were signed by General Cornwallis the next day.

Return to Charleston

Laurens returned to South Carolina. He continued to serve in the Continental Army under General Nathanael Greene until his death. He was in charge of Greene's "intelligence department." This means he created and managed a network of spies. These spies tracked British operations in and around Charleston. He was also responsible for protecting Greene's secret communication lines with the British-occupied city.

Death at Combahee River

On August 27, 1782, at the age of 27, Laurens was shot from his horse during the Battle of the Combahee River. He was one of the last soldiers to die in the Revolutionary War. Laurens died in what General Greene sadly called "a paltry little skirmish." This happened only a few weeks before the British finally left Charleston.

Laurens had been sick in bed with a high fever for several days, possibly from malaria. When he heard that the British were sending a large force out of Charleston to gather supplies, he left his sickbed. He "wrote a quick note to Gen. Greene, and, ignoring his orders and important duties... went to the scene of action."

On August 26, Laurens reported to General Mordecai Gist near the Combahee River. Gist had learned that 300 British troops under Major William Brereton had already captured a ferry and crossed the river. They were looking for rice to feed their soldiers. Gist sent a group with orders to attack the British before sunrise the next morning. Laurens asked for and was given orders to take a small force further downriver. They would man a redoubt (a small fort) at Chehaw Point. From there, they could fire on the British as they retreated.

Laurens and his troops stopped for the night at a plantation house near the Combahee River. Laurens got little or no sleep. He spent the evening "in a delightful company of ladies... and left this happy scene only two hours before he was to march down the river." With his command, Laurens left the plantation around 3 o'clock on the morning of August 27.

Leading a group of fifty Delaware infantrymen and an artillery captain with a howitzer, Laurens rode toward Chehaw Point. However, the British had expected their moves. Before Laurens could reach the redoubt, 140 British soldiers had set up an ambush along the road. They were hidden in tall grass about one mile from his destination.

When the enemy rose to fire, Laurens ordered an immediate charge. This was despite the British having more soldiers and a stronger position. Gist was only two miles away and quickly approaching with more troops. According to William McKennan, a captain under Laurens's command, Laurens seemed "eager to attack the enemy before the main group arrived." He gambled that his troops, "though few in numbers, [would be] enough to help him win glory" before the fighting ended. McKennan thought that Laurens "wanted to do everything himself, and have all the honor."

As Laurens led the charge, the British immediately opened fire. Laurens fell from his horse, fatally wounded. Gist's larger force arrived in time to cover a retreat. But they could not prevent costly losses, including three American deaths.

After Laurens's death, Colonel Tadeusz Kościuszko, who had been a friend of Laurens, came from North Carolina. He took Laurens's place in the final weeks of battle near Charleston. He also took over Laurens's spy network in the area.

Laurens was buried near where the battle took place, at William Stock's plantation. After Henry Laurens returned from being imprisoned in London, he had his son's remains moved. They were reburied on his own property, the Mepkin Plantation.

The Laurens family sold their plantation in the 1800s. In 1936, publisher Henry Luce and his wife Clare Boothe Luce bought it. In 1949, the Luces gave a large part of the former plantation, including a big garden, to the Trappists for a monastery. This site is now called Mepkin Abbey and the Mepkin Abbey Botanical Garden. It is near Moncks Corner, South Carolina. The site is open to the public, including the Laurens family graveyard on the monastery grounds.

Family Life

Marriage and Daughter

On October 26, 1776, Laurens married Martha Manning in London. Her father was one of Henry Laurens's business partners. He was a mentor and family friend whose home Laurens had often visited in London.

Laurens and his new wife moved from London to a home in Chelsea. But Laurens was very patriotic and did not want to stay in England. He believed that honor and duty required him to fight in the American Revolution. In December 1776, he sailed for Charleston. His pregnant wife, who could not risk a long sea journey during wartime, stayed behind with her family in London.

Laurens's only child, his daughter Frances Eleanor Laurens (1777–1860), was born around January 1777. She was baptized on February 18, 1777. Fanny was not expected to live at one point, but she recovered from a successful hip surgery. At the age of eight, after losing both parents, Fanny was brought to Charleston in May 1785. She was raised there by John Laurens's sister Martha Laurens Ramsay and her husband. Fanny later married Francis Henderson, a Scottish merchant, in 1795. Later in life, she married James Cunnington and died in South Carolina at age 83.

Laurens had one grandson, Francis Henderson Jr. (1797–1847). He was a lawyer in South Carolina who died young and did not marry or have children.

Legacy

Historical Tributes

In 1834, Hamilton's son and biographer John Church Hamilton named his youngest son Laurens Hamilton. This name continued for several generations in that part of the Hamilton family.

Nathanael Greene, in his orders announcing Laurens's death, wrote: "The army has lost a brave officer and the public a worthy citizen."

Three years after Laurens died, George Washington was asked about Laurens's character. Washington said that "no man had more love of country. In short, he had no fault that I ever found, unless bravery bordering on recklessness could be called a fault; and he was driven to this by the purest reasons."

Places Named After Him

- Laurens County, Georgia, was named in honor of John Laurens.

- The city of Laurens, South Carolina, and Laurens County, South Carolina, were named for both Laurens and his father Henry Laurens.

See also

In Spanish: John Laurens para niños

In Spanish: John Laurens para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |